Sounding site: listening, mingling, index and reciprocity in the field

by CATHERINE CLOVER, JOHANNA HÄLLSTEN and SHAUNA LAUREL JONES

- View Catherine Clover's Biography

Catherine Clover is a British artist based in Naarm/Melbourne, Australia.

- View Johanna Hällsten's Biography

Johanna Hällsten is a Swedish artist based in London, UK.

- View Shauna Laurel Jones' Biography

Shauna Laurel Jones is an American scholar based in Reykjavík, Iceland.

Sounding site: listening, mingling, index and reciprocity in the field

Catherine Clover, Johanna Hällsten and Shauna Laurel Jones

Sound invites (us) to walk and produce uncertain paths that build a contingent geography between the self and the world in which we live, without insisting on a central or determining authority, neither divine nor scientific. Thus, we remain embodied in the obscurity of what we cannot see rather than positioned on a certain path. (Voegelin, Sonic Possible Worlds, 25)

Prelude

Calls from Blethenal Green (2013), a collaboration between artists Catherine Clover and Johanna Hällsten, explored interactions between human and animal communities in and around St John’s Church, Bethnal Green, London.

The project was motivated by our interests in migration, cultural difference, and social engagement of both animals (specifically wild urban birds) and humans. Location is pivotal in understanding the behaviours of all species; as the identification of place and home are key elements in this process, the project responded site specifically to the church building where the work was presented and interacted directly with the church and wider Bethnal Green community. We investigated local relationships through voice, language and song, translation and dialogue. With communication at the centre of the project, we developed a theme of call and response through a local choir, local birdsong and the manual ringing of the newly renovated bells in the church belfry. The project included performance, moving image projections and recorded sound. We invited Shauna Laurel Jones and Amy Sherlock to respond to the ideas of the project in two short essays, which were included in an exhibition catalogue that allowed for an expanded response to the themes and the site (see Jones' catalogue text here).

The final exhibition consisted primarily of field recordings from the local area, both inside and outside the church. They included: the birds’ voices as we (and many others) fed them in the park; our voices reading to the birds from field guides; members of the congregation singing as they cleaned the church; the voices of migrants learning English in the crypt; our voices reading lists of the local birds; members of the congregation reading lists of the local birds and commenting on their experiences of these birds including stories that grew from these interactions. The soundclips and images included in this essay are a mix of final works that were in the exhibition and others that were recorded as part of the process, together with work in response to our reflections on the project now.

Catherine Clover and Johanna Hällsten, Calls from Blethenal Green, St John’s Church, Bethnal Green, London (2013)

Through our multidisciplinary practices and research, Cath, Johanna and Shauna have a continued relationship with the ideas present in Calls from Blethenal Green. For this collaborative essay, we revisited and extended the conversation about the project. In particular, we sought to explore the role listening plays in the process of sensing and making sense of place while in the field. Can conscientious listening help level an unequal playing field?

Catherine Clover is a British artist based in Melbourne, Australia, Johanna Hällsten is a Swedish artist based in London, UK and Shauna Laurel Jones is an American scholar based in Reykjavík, Iceland.

Movement – Melbourne

One of the many aspects that I found particularly interesting during our collaboration was the discovery of Sir John Soane’s library and the books he owned on natural history. Sir John Soane was the architect of St John’s Church, Bethnal Green (built 1826) and this led Johanna and me to his home on Lincoln’s Inn Fields in Holborn, now the idiosyncratic Soane’s Museum. His library, which is now accessible to the public, was a rich and revealing resource for us. Some of the books Soane owned detailed earlier attempts at classifying the natural world; that is, classifications that existed prior to Linnaeus’ taxonomy that we still use today. These classifications, some of which were still being produced some time after Linnaeus’ publication, were fascinating with their inclusion of the imaginative, myth and anecdote as much as, or as well as, empirical scientific fact. “Of rapacious Birds with Wings shorter than the Tail” (Brookes 27) and “Of Birds with a Straiter Bill, that are not able to fly, on account of the great Bulkiness of their Bodies, and Shortness of their Wings” (Brookes 77) are a couple of examples from Richard Brookes’ 1763 list of how birds could be classified. The whimsy and speculation in these categories was appealing to us because it suggested both a more inclusive and creative way of thinking about these birds, appropriate for a re-thinking of how we might relate to them today. What we discovered, as Michel Foucault notes, was that

Until the time of Aldrovandi (1522–1605), History was the inextricable and completely unitary fabric of all that was visible of things and of the signs that had been discovered or lodged in them: to write the history of a plant or an animal was as much a matter of describing its elements or organs as of describing the resemblances that could be found in it, the virtues that it was thought to possess, the legends and stories with which it had been involved, its place in heraldry, the medicaments that were concocted from its substance, the foods it provided, what the ancients recorded of it, and what travellers might have said about it. The history of the living being was that being itself, within the whole semantic network that connected it to the world. (Foucault 129)

The Medieval era sought to distinguish animals primarily through their activities, but Linnaeus’ taxonomy sought to identify similarities between species through a focus on the physical body. While looking for similarities, paradoxically, Linnaeus’ taxonomy separates humans from animals; for Linnaeus man dominated nature and was separate from it. Prior to Linnaeus’ system, ways of classifying animals were subject as much to speculation and fantasy as to fact. While we may laugh today with our focus on scientific empirical fact and observation, this approach promotes a broad and inclusive thinking about the possibilities of the unknown as much as a focus on the known. It was these broader, older, more inclusive forms of classification that gave us a kind of permission, if you like, to explore the potential of cross-species communication, the possibility of talking to the birds.

Counterpoint – Reykjavík

According to Jones family lore, when my brother was little he had his own avian classification system that recognized two forms: walkin’ birds and flyin’ birds. By his intuitive typology, the same individual bird could change categories by virtue of its locomotion at any given moment. Such a system with flexible boundaries can’t compete with that of Linnaeus or even with that of Brookes, but for a young mind trying to make sense of the distinguishing features of things and beings in the world, it seems perfectly logical.

And for my less flexible adult mind? I grasp the oystercatcher, tjaldur, that conspicuous wader, best as a walkin’ bird, characterized by her methodical steps on the mown grass or across the moor; I’m moved to channel the vibrations as she drums the ground for food with her proud orange bill; then I lose her when she takes wing, still equally conspicuous but less distinctive to my sensibilities. But the Arctic tern, kría, with her stubby legs rendering her improbable on land, reaches poetic heights in the air, careening and diving and rising again on elegant wings that take her impossibly to the Antarctic and back. Although she does walk sometimes, in my eyes she is only a flyin’ bird, one who stirs my imagination like no other. Her migrational return, announced with a piercing familiar cry, is met with a sigh across the land, then a gasp as her lyrical aeronautics enliven the skies.

Movement – Reykjavík

In asking me to contribute from a distance to Calls from Blethenal Green, your essay prompt concerned the issue of language as so-called proof of human intelligence and superiority over other living creatures, and this sense of superiority as fundamental to our current “environmental crisis.” My suggestion in the catalogue text was that perhaps we’ve been led astray in modern times by trying to understand animal communication literally, or linguistically, rather than attempting to relate to its non-symbolic, expressive qualities. I’ve since become acquainted with ecologist and anthropologist David Abram, for whom the rupture of humankind’s meaningful connection with the rest of the world came with the origins of written alphabetic language. In Abram’s view, the abstract and symbolic logic of script displaced humans’ ability to interpret the speech of nature as intelligible. Further, for Abram, oral culture was better suited for honoring Foucault’s “unitary fabric” of the world.

Without writing, knowledge of the diverse properties of particular animals, plants, and places can be preserved only by being woven into stories … Stories, like rhymed poems or songs, readily incorporate themselves into our felt experience; the shifts of action echo and resonate our own encounters—in hearing or telling the story we vicariously live it, and the travails of its characters embed themselves into our own flesh. (Abram 120)

Some of the oral cultures Abram describes honor the concept of shapeshifting between humans and other life forms. Maybe to some of these cultures, a system that would permit the categorical shapeshift of a walkin’ bird to a flyin’ bird would be more logical than the fixed imperative of the Linnean system! But even for those of us to whom Linneaus makes the most sense, categorical shapeshifting happens all the time, as animal geographers Chris Philo and Chris Wilbert point out. When animals, especially through acts of their own agency, “destabilise, transgress or even resist our human orderings, including spatial ones” (Philo and Wilbert 5), they morph from pet to pest, useful to harmful, cuddly to threatening—and then back again.

I side with Abram, for whom the “disinterested” sciences do not suffice in explaining our daily lives and for whom intuitive and phenomenological engagement with the world holds the key to true meaning. Intuitive engagement often disrupts categorical boundaries, shedding new light on how things are compared to how they “should” be. Does communication, or at least attempted communication, with other species further that process?

Counterpoint – London

Sitting on my sofa reading about the biophony, I hear a lot of scurrying and movement outside in the garden – a cat or a squirrel, I thought. It kept happening over and over in rapid succession; curious to see what was happening, I got up to have a look. The resident squirrel suddenly popped up on top of the fence with something in his hands. We were both so startled to see each other that we stopped dead still in our tracks. I said ‘Hi’; he looked at me intently, then proceeded to eat his afternoon snack. This went on for about five minutes, us staring at each other eating afternoon snacks. Once we had finished our snacks, we both went off on our merry ways.

Movement London

To greet one another is the most common form of communication across all species, to signal a ‘hello – I am here and you are too’.1 It’s a habit of mine to say ‘hi’ to all creatures I encounter, especially in the garden. Perhaps a futile exercise, yet it feels necessary to introduce myself, to acknowledge that I am aware of their presence. Why do I need to acknowledge it with a sound, though – or to be specific, a greeting? They already know I am there; maybe I persist in doing this because I somehow feel I am trespassing in their space, although it is a shared space.

The cohabitation of the world, of being one with the world, is a familiar philosophical concern, with phenomenology and its many variants now being readily used to engage in theorisations around animal–human relations. Such a model is especially useful in moving away from a Cartesian dialectics of eye-mind superiority, and in acknowledging that we are of the same environment and world. Lived experience is key here, both in general terms regarding understanding the world around us, and also in how we approached the Calls from Blethenal Green project and the site/field. We are not separate from the world we live within and are one with; the distancing is artificial; movement situates us, enables us to create connections within a place (Casey 1997; Merleau-Ponty 1989; Straus 1966). Yrjö Sepänmaa draws attention to our problematic relationship with our environment:

the environment is easily forced into a foreign mode of observation by raising the similarities to art to a more exalted position than the environment’s own system would grant them. (qtd. in Saito 17)

We have such a strong urge to instrumentalise and anthropomorphise our surroundings that we easily fall back into a position of reproducing hierarchies, systems, categorisations and, as a result, descriptions. We tried to actively immerse ourselves within the Bethnal Green field/place and challenge our preconceived attitudes and ways of behaving within that place, by focusing on listening and an embodied experiencing.

Gathering an understanding of the historical aspects of the culture and environment around the church enables us to glean how the local bird population may have come to be what it is. Bernie Krause comments on how the biophony is changing and in many cases diminishing in urban and wild environments:

When habitat alteration occurs, vocal critters have to readjust. I’ve noticed that some may disappear, leaving gaps in the acoustic fabric. Those that remain have to modify their voices to accommodate changes in the acoustic properties of the landscape. (Krause 80)

We spent a lot of time listening to the environment we were immersing ourselves in, which meant that a plethora of species, languages and communities were included. We heard some of what they were saying, tuning into it. The texts in the catalogue, and the dialogues with the writers, afforded us a critical distance from this immersion into the environment and offered us alternative positions to consider the processes in the field.

Catherine Clover and Johanna Hällsten, Calls from Blethenal Green, St John’s Church, Bethnal Green, London (2013)

Movement – Reykjavík

Hearing some of what the local birds were saying, and honoring them as them, in all their plurality, is in itself a gracious and critical act. It’s the very opposite of what Derrida describes as violence committed by the Platonic ideal or chimerical notion of “the animal,” which is how we have come to conceptualize other species—as a lump sum incapable of self-reflection or retort. He pronounces humans as

first and foremost those living creatures who have given themselves the word that enables them to speak of the animal with a single voice and to designate it as the single being that remains without a response, without a word with which to respond. (Derrida 32)

To the contrary, you listened to individual bird voices, responded to them, and allowed them to respond back again. Calls from Blethenal Green was in that sense an attempt to undo the violence committed by the singular idea of the Animal.

Counterpoint Melbourne

The current season is winter ending, the birds are singing and getting itchy, it’s almost the right time to see the birds arriving for the southern summer. I am walking along the Merri Creek, a small stream which runs through the northern suburbs. I hear a kookaburra call and this is unusual in the urban setting. It was the start of the call, the quieter

cucucucucucucucucu

The bird did not go into full voice, the loud laughter of

oh oh oh ah ah ah ah hahahahahahaha hahahahahahahaha

Movement Melbourne

Building on Shauna’s brother’s categories of walkin’ birds, I think of birds that swagger as if their legs are too wide apart (ravens and crows) birds that hop (blackbird, sparrow) birds that walk and bob their heads (pigeons) birds that walk and don’t bob their heads (seagulls).

We are amongst only a small group of animals (that we know of) that have to learn our language; our communication is not in-built but is learnt, both at a young age but also throughout life. We play and improvise with language all our lives and I don’t see why other language learners – other animals – wouldn’t do the same thing. This idea of improvisation inspires much of my artwork.

Humans are not born knowing the sounds that are relevant to the language they will speak. Vocal learning is … a rarity in the natural world, but it is not unique. The short list of known vocal learners among animals includes parrots, some hummingbirds, bats, elephants, marine mammals such as dolphins and whales, and humans. But by far the most numerous vocal learning species (at about 4000) are the oscine songbirds. From an ontogenetic perspective, the acquisition of speech and birdsong have compelling parallels. (Brenowitz, Perkel, and Osterhoot 1)

I have also found the relationship between the visual orientation of the written word and the sonic orientation of the sound of the word to be a rich space to explore when considering the animals that live around us, and I have been doing this using homophonic translation, where sound is prioritised over meaning. This is the method I use to transcribe the birds’ voices to the written word.

Catherine Clover and Johanna Hällsten Calls from Blethenal Green (learning bird names) St John’s Church Bethnal Green London (2013) - excerpt duration 1' 28”

In terms of categories and lists, and the way we organise the chaotic world around us, it is experimental French writer Georges Perec to whom I turn because of his humour and subtle complexity.

Like everyone else, I presume, I am sometimes seized by a mania for arranging things … the arrangements I end up with are temporary and vague, and hardly any more effective than the original anarchy… The outcome of all this leads to truly strange categories. A folder full of miscellaneous papers, for example, on which is written ‘To be classified’; or a drawer labelled ‘Urgent 1’ with nothing in it (in the drawer ‘Urgent 2’ there are a few old photographs, in ‘Urgent 3’ some new exercise-books). In short, I muddle along. (Perec 196)

Counterpoint – Melbourne

Today on the dog beach the water is clear and the sea melts into the sky in

greys whites blues cormorants fish silently gulls call

akak akak akak

Spring keeps springing all around. Jasmine, with its deeply rich scent and dark magenta buds that turn to small white flowers, envelopes Melbourne. The birds are active, blackbird and wattlebird provide melody and rhythm first thing, with the doves, ravens, mynas, sparrows, honeyeaters joining in later. The swallows swoop over the flat grassy oval.

I have been transcribing blackbird song this spring. Even though their song is louder and slower here than in Europe (they have adapted their song to compete with the raucous Australian native birds they live with) for a long time I avoided transcribing it as the song is fast and complex. At dawn the blackbirds start first and the wattlebirds a little later, with their loud throaty rasps. High fast complex whistles of the blackbird, I don’t catch them all.

weo peep peep weoh peep peep peep tra eep eep

eep eep trrrr rrrrr trup trup

tree tree tree rrrr eeoh ee trrr eee

oh ee or tra wee wee trrrr

ah wee trrr ah wee ah trrr

eee eee eee

tra tra tre tre tre tre reep reep reep

woh trrrr eeep eep trrrr

ah we ee-ee-ee-ee

ah wee up tree tree tree

eeowp eeowp trrr trrr

pause

pup pup pup pup pup pup pup pup pup

Intermittent wattlebird

ock ock ock

ee-ee ock ock ock

ock ock ock

Catherine Clover and Johanna Hällsten, Calls from Blethenal Green (robin, blackbird, wood pigeon, plane), St John’s Church, Bethnal Green, London (2013) - excerpt duration 2'18”

Movement – Melbourne

During Calls from Blethenal Green the pigeons seemed to be the birds we had most interaction with. We spent time in the well-tended park next to the church during the early summer. When I look at the photos, I can see the humidity in the air and realise that this is what defines the softness of English summers. The park was always well used by both people and birds. We spent time reading field guide entries about the pigeons to the pigeons, and we ate our lunches and fed them as we did so.

Catherine Clover and Johanna Hällsten, Calls from Blethenal Green (reading together), St John’s Church, Bethnal Green, London (2013) - excerpt duration 1’ 30”

Catherine Clover and Johanna Hällsten, Calls from Blethenal Green, St John’s Church, Bethnal Green, London (2013)

By reading the story within earshot of the birds means that they hear our voices and potentially share in the event, and the event can become a cross-species one. By enacting the story in this way, the solitary act of silent reading is made public, which “bring(s) reading back to what it primarily is: a precise activity of the body” (Perec 175). Reading in silence is a relatively recent phenomenon and only became a widespread activity from the tenth century in the West. In AD 384, Saint Augustine observed Saint Ambrose reading silently and

When he read … his eyes scanned the page and his heart sought out the meaning, but his voice was silent and his tongue was still … when we came to visit him, we found him reading like this in silence, for he never read aloud. (St Augustine cited in Manguel 1996)

A sonic understanding of place is articulated by Kumi Kato’s definition of ‘soundscape’ (Kato 80) where she identifies that a reciprocal relationship with place is formed through a careful and attentive listening, a “dialogical and communicative” relationship (Kato 81) that can engage and define a community. As an example she cites the ancient role of the ama (sea women) of Japan, China and Korea, who “free dive (i.e., without oxygen tanks)” (Kato 86) for abalone and other shellfish and maintain a sustainable relationship with the sea. The sound of the women taking breaths between their dives is known as isobue, or sea whistle (Kato 86), and symbolises their respect and deep connection to their environment. Their connection to the sea is so great that they resist the introduction of modern equipment and say that “The facemask would allow divers to ‘see too well and take too many’” (Kato 87), and of wetsuits, “‘Of course the wetsuits keep you warm, but you cannot feel the ocean’, while another noted ‘It felt rude to go into the sea with that black thing on’” (Kato 87).

Counterpoint Reykjavík

Ducks say quack quack in English and bra bra in Icelandic but my favorite ducks say neither. The sweet rolling coo of the eider as she calls to her brood rhymes with the undulation of the water at a calm low tide, soft as the down in her nest and gentler than the gentlest lullaby.

Counterpoint – Melbourne

Dogs bark, traffic muted. Occasionally the low pitch sonorous whistles of the Australian magpie join in with the blackbirds and wattlebirds. A man is regularly dropped off early outside the house.

car door slams a brief exchange

bam bo bam bo na la ree ar nah la

car pulls away train horn chord in the middle distance

Catherine Clover and Johanna Hällsten Calls from Blethenal Green (learning more bird names), St John’s Church, Bethnal Green, London (2013), excerpt duration 3'16”

Counterpoint London

Our summer and early autumn has been very windy, making it hard to pinpoint the bird sounds. Whilst cycling round in Victoria Park, I finally hear the parrots that we heard on one of our walks around the Bethnal Green area, Cath. It made me stop cycling and I found myself smiling and completely enthralled by the sound. Of course I could not see them; they are masters of disguise, after all. It made me think of our project and the Bethnal Green area being used to trade in birds and other animals, and how these have escaped capture and pursued freedom, establishing a new life in a different country.

On this day, I also got to witness this unison engagement of the field by the crows, and it was absolutely stunning how they moved from spot to spot, avoiding the little puppy trying to chase them away wherever they decided to sit down (or rather stand down, rest, eat, chat, squabble…who knows – why do we need to know?)

Johanna Hällsten, The crows in Victoria Park (2015)

Movement London

Perec’s notes on classification are very pertinent to our discussion and in general, I believe, and it makes me think of Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities (1997) where the same city is explored from a multitude of angles, views, experiences and senses – and crucially through time, over a period of duration. Classifications often change, are amended or altogether deleted, erased or moved to a new category over centuries, as can be seen in the taxonomy of plants where this often happens. Addendums to an already ‘established’ system – the categories and systems are continuously re-written, but one question that always persists with regards to this is: for whom? For whom are these classifications better, more helpful or accurate – who is benefitting from them?2

How does language play a role in these classification systems, both concerning the animal/human relation and how we interpret sonic-visual environments? Who is speaking to whom? As a foreign language speaker, I found these points on language interesting: one could ask, ‘How are we to understand another species when we cannot even understand our own species fully, on a basic level of culture and language differences?’ – too big a question here. But during our investigations, or rather our searching and gathering of information, material, data, leading up to the exhibition at Bethnal Green, we used many different approaches to understanding the place, the particularities of that place (historical research, library catalogues, interviews, listening, recording and so on) and its multiplicity of languages and cultures. Hildegard Westerkamp’s (1974) thinking and instructions on how to engage with(in) our environment from a sonic perspective using soundwalks and a more attentive listening engagement were very helpful in the process of the research for the exhibition.

We were at times very self-conscious about our methods and how we fitted in or trespassed on their (human and animal) land. We spoke of this at the time, and have since, between the three of us – what makes work in the field fieldwork? There is an unease between the scientific and the creative research practices of fieldwork: how do the two parts of the word relate and what do they mean here? To field a question, to play on a level playing field, to investigate the field, a location, a place outside of the laboratory, a field filled with crows…

To work, when does work stop and play begin?

Catherine Clover and Johanna Hällsten, Calls from Blethenal Green (rehearsal), St John’s Church, Bethnal Green, London (2013) - excerpt duration 3'

Movement – Reykjavík

Fieldwork may involve trespassing, as you suggest, Johanna, but from my remote location and having never even visited that part of London before, I’ve felt sometimes like I’m trespassing on the Blethnal Green project. The field recordings of the bells and of the birds you sent me during your residency didn’t quite bridge the distance between me and the site. However, they did successfully afford me some insight into your situatedness there, your burgeoning investment in the area, your process of becoming attuned to the environment and its inhabitants. For me, your fieldwork was a matter of your becoming ambassadors, despite the fact that neither of you lay claim to Bethnal Green. And for me, in making meaning of someone else’s fieldwork, trust assumes great importance: not so much trust in outcomes, but trust in the authenticity of the engagement and in the sincerity of the report. Your careful listening above all earned my trust.

Counterpoint – Reykjavík

My research this summer has taken me outside regularly for my own fieldwork, but still, most of my time is spent inside analyzing, typing, editing. At my desk in a third-floor reading room, I’ve got a view over my right shoulder of Vatnsmýrin, a protected wetland, with downtown Reykjavík in the midground nestled against a background of the mountains across Faxaflói Bay, but firmly in between me and the view are panes of solid glass. They slant upwards over my head and sometimes I lean back in my chair and watch the birds soaring in the sky above. There’s a raven who seems to have gotten on the bad side of a couple of seagulls, and I regularly see the three members of the two species circling and swooping antagonistically around each other, right above me. Always in the imposed silence of the glass-bound reading room.

Counterpoint London

Walking down to the tube in the very early morning, it’s dark and cold, autumn is in full swing, the leaves rustling against the pavement. I’m tired and only the kraa’s of the crows sitting on the rooftops bring my attention out of the bubble that my mind is in – noticing the very close sonic environment I am traversing and adding to. The tits add their comments to the conversation – we are all aware of each other – my internal dialogue stops and I focus my attention on listening to the place as I continue the walk.

Movement London

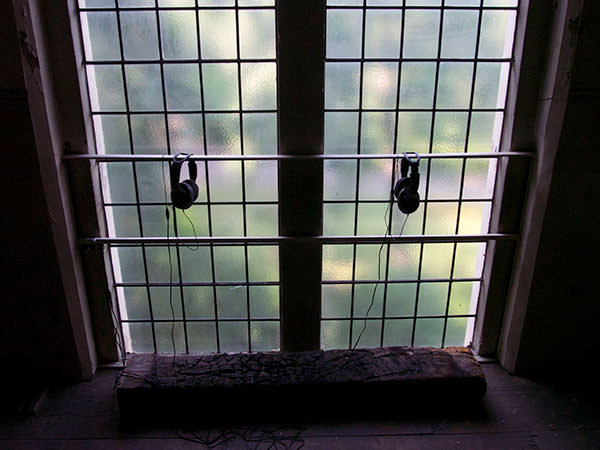

To allow the words to come off the page and become communal was essential: similarly, we arranged for the bells to chime without a message. A simple ringing of the bells up and down is a reaching out.3 The difference between the sound heard inside the bell tower and that outside in the park, and beyond, is staggering. To bring the sounds from outside in in the surround-sound piece again allowed for this traversing and eroding of boundaries to take place. The use in the work of various forms of communication between and within different communities using the church allowed new connections to be forged. We were motivated by a desire to share our listening with others, whilst realising that no listening experience is the same, as environmental conditions change and our cultural, historical and social experiences are different. For example, working with language class in the crypt allowed a discussion across cultures about birds, including listening and noticing the local environment they came to every week. Furthermore the belfry was one of the main locations of the exhibition along with the first floor seated area, accessed via the same staircase that led to the belfry, two areas otherwise not readily accessible to the general public.

The bells do not ring freely anymore, and haven’t done since the exhibition. The automated chiming on the hour, quarter past, half past and quarter to is effective in bringing your attention back into the space surrounding the church for a moment, but it does not compare to the sustained ringing of the bells by hand. The automated chiming drifts into the normal humdrum and cacophony of the Bethnal Green area.

The bells were manually rung several times during the exhibition by bellringers of the local area, and myself (a mere beginner), including on the opening night. It brought people from the local area to the church, as they had not heard the bells ring before and were curious to listen more closely and to see it happening. Many commented upon the difference between hearing from afar, immediately outside and inside in the belfry, enjoying this new experience of their local everyday environment. Several left their flats to come and listen, without knowledge of the exhibition. The belfry was used by the local bird population prior to its renovation, and they often rest on the roof of the church, but swiftly move to the lawns and trees as the bells start ringing.

Catherine Clover and Johanna Hällsten, Calls from Blethenal Green, St John’s Church Bethnal Green London (2013)

Catherine Clover and Johanna Hällsten, Calls from Blethenal Green (learning the bells), St John’s Church, Bethnal Green, London (2013) - excerpt duration 1'03”

Catherine Clover and Johanna Hällsten, Calls from Blethenal Green, St John’s Church, Bethnal Green, London (2013)

The body is essential in the bells becoming a tool for communication beyond the mechanistic recording of time. The ringer has to use her whole body to enable the bell to move and to do so in time, whilst simultaneously listening out for her own bell, the others’ bells and instructions for changes. A complex bodily engagement with the others, the bell and sounds take place over a sustained period of time.

“I hear a voice, and in doing so I recognise someone. This someone encircles me already with their speaking. … place also acts as a form to speech.” (LaBelle 11) LaBelle speaks about the human voice whilst sitting in a cafe. I’d like to extend this notion of voice and how place forms that voice and its utterances to include all species, and in particular here the birds of Bethnal Green and beyond. Which leads me to Nancy and his thinking on listening, body and place.

… it is a question of going back, or opening oneself up to, the resonance of being, or to being as resonance. (Nancy 21)

Nancy speaks of the body as a resonant being: not only does it resonate and makes sounds, but it also acts as a resonating chamber for others. This is true of all beings, not only humans. The question regarding language and understanding still lies in how we perceive those resonances/sounds/utterances and whether those have meaning or not — do we have the tools to determine meaning? We attempted to communicate with the local birds and diverse human communities, but whether we achieved a dialogue with the birds is questionable. The location/field did afford us the opportunity to open the possibility for dialogue to form between humans of different cultures and animals of various species. There was and still is a constant moving towards understanding and communicating with others, although it may never be fully realised.

This makes me wonder whether Cath’s transcriptions of bird sounds could be understood by non-English speakers, or if they are inherently English?

Movement Melbourne

Language is a good point, and we’ve had some discussions about this Johanna haven’t we? I think my way of transcribing the bird sounds is inherently English, yes, and not just English in terms of the broader language but my heritage in England. I use English English as distinct from Australian English. Speaking the same language in a different country is deceptive because as an outsider who speaks the same language as the local population it lulls you into a false sense of cultural understanding and comprehension. This has been my experience in Australia and it has taken me years to identify. As migrants all three of us have had the experience of settling into a new country and a new culture. You Johanna have had the experience of communicating in another language (I'm not quite sure about your experiences, Shauna, I'm interested to find out). Language is culture, yes, but language is also, very importantly, place. Language is dialect, accent, idiom, creole, pidgin, vernacular, patois (and as we know birds’ voices also change according to place as well). These aspects of language are specific to place, and Deleuze’s idea of a ‘language within a language’ could be useful here. The language of place can be broken down into very small increments because it applies to different parts of countries as well: regions, localities, districts, neighbourhoods and so on.

Sound casts doubt on whether a town, an architectural site, a room, a spatial landmark and border actually exists as a solid (spatial) fact, however firmly it is established on a map, or evidenced in a slide collection, or a photographic tourist brochure. The sonic sensibility understands place through the uncertainty of its dynamic, and assesses belonging through the doubt of perception. It focuses on the inhabitant and his production of a place for him, rather than on the symbolic weight of a collective place or the possibility of visiting it. (Voegelin “Listening to Noise and Silence” 144–145)

Catherine Clover and Johanna Hällsten, Calls from Blethenal Green (sweeping), St John’s Church, Bethnal Green, London (2013) - Excerpt duration 3'24”

Movement Reykjavík

One of the most poignant reflections I’ve heard on English as a lingua franca came from a former student of mine from the Faroe Islands. She said, “I feel sorry for English speakers. Wherever they go in the world, they never have any privacy.” How true! To speak English is to be defenceless against eavesdropping, open to analysis. Perhaps it’s counterintuitive, but I feel a greater sense of privacy while conversing in the mother tongue of my adopted home: I try to keep all public exchanges in Icelandic to maintain a comfortable distance between myself and those around me. I do feel vulnerable while using my shoddy Icelandic, but I feel more vulnerable when it’s revealed that I “have” to use English in order to communicate properly.

The typical lament from the scientific establishment is that it’s such a pity that other animals have such a limited ability to learn human languages. The more insightful lament is that it’s a pity we have such a limited ability to learn their way of communicating. I’m trying to imagine myself transcribing bird calls as you described yourself doing, Cath, and I imagine it to be a humbling exercise, bringing to the fore the boundaries of my comprehension and perception. Was it a twoo-hee-hee or a tyuu-eeee-yeee? Were there extra syllables or added inflections there that were too fast and nuanced for me to even hear? I read just yesterday that humans and birds have very similar neural pathways for vocal learning (Jarvis 2004; Balter 2010), which is both exciting and frustrating: if our languages are so similar, why are we still worlds apart in understanding each other? But as you said, Johanna, we humans misunderstand each other all the time, too, even when we are speaking the same language.

My favorite person to speak Icelandic with is my mother-in-law. She speaks very little English, so she’s extraordinarily patient with me, and I’ve pushed myself to converse with her about increasingly complicated matters. I make lots of basic mistakes, and sometimes it takes me a long time to spit out my thoughts as I try to find ways around my limited vocabulary. Her willingness to listen, in and of itself, makes a tremendous difference and continues to help me improve. Are there birds who might be willing to listen to us as we stumble along in their tongue? I wonder, for instance, about the patience and the interest of the nightingales David Rothenberg tries to make music with in Berlin, birds who “actually seem to enjoy singing after and amidst the everpresent noise of humans” (Rothenberg 222). Perhaps they’re not the only ones.

Counterpoint – Reykjavík

The quickening breeze through the marsh rustles the husks of seed pods opened and emptied with haste before the frost sets in. And there’s a certain urgent chattering of the thrushes when the rowan berries are at their ripest: I can close my eyes and hear it’s autumn.

Cadence

New birds in a new field: as we collaborated on this essay, a new project began to unfold in the form of a short residency and joint exhibition in 2017–18. The three of us will convene in Iceland and go out in search of avian aesthetics on this volcanic island bordering the Arctic Circle, finding out whether the birds, local and migrant, will choose to return our all-too-human aesthetic regard. Building on our understanding that the categories we create to understand the world constrain our engagement and create boundaries and distance between ourselves and other living things, this new project will use listening and sound, both linguistic and non-linguistic, as a means of communication. The project proposes that through a heightened engagement with the acoustic, boundaries can be dissolved or at least blurred so that proximity, through resemblances or likenesses both between species and within species, is the focus of our attention.

As listening is active rather than passive, it is the first step in exchange and communication. By attentively listening we can acknowledge our place in the world and our connection to it rather than our separation from it. By listening to the birds local to Iceland, this project will extend the work undertaken at Bethnal Green and explore a range of voicings or articulations that respond to and enunciate site, the field, through reflection and resonance.

Works Cited

Abram, David. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-human World. New York: Vintage Books, 1996.

Balter, Michael. “Evolution of language, animal communication helps reveal roots of language” Science 328.5981 (2010): 969–971.

Brenowitz, E.A., Perkel DJ., and Osterhoot, L. “Language and Birdsong” Brain and Language: A Journal of the Neurobiology of Language 115:1&2 (2010): 1-148. 8 March 2011 <http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/0093934X/115/1>.

Brookes, Richard. Natural History of Birds. London: Sir John Soane’s Library at The Soane Museum, 1763.

Calvino, Italo. Invisible Cities. London: Vintage Classics, 1997

Casey, Edward. The Fate of Place: A Philosophical History. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1997.

Derrida, Jacques. The Animal That Therefore I Am. Ed. Marie-Louise Mallet. Trans. David Wills. New York: Fordham University Press, 2008.

Foucault, Michel. The Order of Things London: Tavistock, 1970.

Jarvis, Erich D. “Learned birdsong and the neurobiology of human language” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1016 (2004): 749–777.

Kato, Kumi. “Soundscape, cultural landscape and connectivity” Sites 6 (2009): 80-91.

Krause, Bernie. The Great Animal Orchestra Oxford: Profile Books, 2012.

LaBelle, Brandon. “Misplace - Dropping Eaves on Ethics” in Hearing Places: Sound, Place, Time, Culture, ed. R. Bandt, M. Duffy and D. MacKinnon Newcastle-upon-Tyne: Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2009

Manguel, Alberto. “The Silent Readers” in A History of Reading Stanford University:1996. 18 June 2011 <www.stanford.edu/class/history34q/readings/Manguel/Silent_Readers.html>.

Merleau-Ponty, Maurice. Phenomenology of Perception. Trans. C. Smith. London: Routledge, 1998.

Nancy, Jean-Luc. Listening. Trans. C. Mandell. New York: Fordham University Press, 2007.

Perec, Georges. Species of Spaces and other Pieces Trans. John Sturrock. UK: Penguin Books, 1997.

Philo, Chris, and Wilbert, Chris. “Animal spaces, beastly places: An introduction.”Animal Spaces, Beastly Places: New Geographies of Human-Animal Relations Eds C. Philo and C. Wilbert London and New York: Routledge, 2000. pp. 1–34.

Rothenberg, David. “The concert of humans and nightingales: Why interspecies music works.” Performance Philosophy 1 (2015): 214–225.

Saito, Yuriko. Everyday Aesthetics Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

Straus, Erwin W. "Lived Movement." In Phenomenological Psychology, ed. Erling Eng London: Tavistock Publications, 1966.

Voegelin, Salomé. Listening to Noise and Silence: Towards a Philosophy of Sound Art. New York and London: Continuum, 2010.

Voegelin, Salomé. Sonic Possible Worlds: Hearing the Continuum of Sound. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2014.

Westerkamp, Hildergard. “Soundwalking” in Autumn Leaves: Sound and Environment in Artistic Practice, ed. Angus Carlyle Paris: Double Entendre, 2007

Footnotes

- Hello originates from the word hollo/holla (16th century) – at first an exclamation, then an expression of surprise before it became used as a greeting.↩

- With regards to the addendum, “I am very fond of footnotes at the bottom of the page, even if I don’t have anything in particular to clarify there” (Perec 11).↩

- With many thanks to Stephen Jakeman and the bellringers of Friends of Hackney Bells at St John-at-Hackney Church, London, the ringing of the bells was possible.↩