The Extraordinary Ordinary at the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale

by LAURA FISHER

- View Laura Fisher's Biography

Laura Fisher is an arts researcher and sociologist, and post-doctoral research fellow at Sydney College of the Arts.

The Extraordinary Ordinary at the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale

Laura Fisher

Introduction

This article is based on a recent field research trip to the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale in Niigata, Japan. It is a testing ground of sorts, for developing an ethnographic approach to the study of socially engaged art projects. I’m particularly interested in how ethnography might help us better understand socially engaged art’s liminal position between the art world and the spaces of the everyday. Interpretive and retrospective accounts of these kinds of projects don’t often include the ‘first voice’ of participants, and this points to a troubling paradox. Socially engaged artists depart from art’s specialist and insular spaces and deliberately make themselves vulnerable to the judgements of what Thomas Hirschhorn calls the ‘non-exclusive audience’. However art scholars rarely permit that audience or public to be opinionated agents of an art encounter. As artist and educator Pablo Helguera points out in his book Education for Socially Engaged Art, in the case of projects in which ‘the experience of a group of participants lies at the core of the work, it seems incongruous not to record their responses’. He suggests that ‘[i]f these individuals were the primary recipients of a transformative experience, it should reside with them to describe it, not the artist, critic, or curator’ (Helguera 73-74). This foreclosure cannot only be explained by the difficulties associated with collecting participant testimony. The real obstacle lies with art discourse itself, which struggles to accommodate opinions that show how contingent our sense of art’s value and meaning is. But there is much to be gained by crossing this threshold, particularly if we wish to understand what socially engaged art actually does in relation to the tasks it sets itself.1 Ethnography, or indeed the kind of primary research that informs a great radio documentary, can reveal a great deal about how art projects concerned with social change intersect with the specific material, political and social circumstances of the moment. And if we are genuinely interested in how art can be consequential, then the opinions of the non-art literate public who engage with art incidentally have much to teach us about the nexus of art, subjectivity and trajectories of social transformation.

Figure 1: Terraced rice fields, Echigo Tsumari region. Photo: Laura Fisher

Figure 2: Village, Matsudai area, Echigo Tsumari region. Photo: Laura Fisher

Founded in 2000, the Echigo Tsumari Art Triennale (hereafter ETAT) is a one-of-a-kind event that takes place in a mountainous, predominantly rice farming region in the Niigata Prefecture, north of Tokyo. The region is roughly 760 square kilometres in size, and comprises several small towns and villages and many tiny communities made up of only a cluster of households. Residents experience very hot, humid summers and long, snowy winters which historically would isolate villages from each other for several months.

During the Triennale, visitors are invited to discover hundreds of permanent and semi-permanent artworks installed in fields, houses and schools throughout the region, as well as performances, workshops and other participatory events. These works are created by both established and emerging artists from Japan and around the world, and are in many cases produced in collaboration with local people.

Figure 3: Hachi and Seizo Tashima. ‘Museum of Picture Book Art’, installation detail (2009-2015). Installed in Sanada Elementary School, which closed in 2005. Photo: Takenori Miyamoto and Hiromi Seno.

My fieldwork lasted two weeks, during which I travelled by car to as many art sites as I could (with husband and 5 year old son in tow in the first week). During that time I spent four days with a Japanese interpreter, conducting interviews with artists, volunteers, event organisers and local men and women. These field notes, audio recordings and translated transcripts have been the departure points for several strands of research into ETAT. The particular strand taken up in this article concerns how the Triennale creates a situation, or a ‘field’ for art that overturns the notion that art is exceptional and located at a privileged distant from everyday life. My reflections largely focus on what the individuals I interviewed taught me about the art’s relationship to the specificity of the Echigo-Tsumari environment, different practices of labour and care, and the crisis of depopulation.2

Background to the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale

...for generations before us, like people in their forties and fifties, they grew up being told that cities were better than these areas. They were taught to expect that they should go to a city, work and earn lots of money there when they grew up. That is why there aren’t many people left, and this situation came about. (Hotaka, Tsunan area).

Few socially engaged art projects ask art to “matter” as much as ETAT. As is well known, Japan faces unique demographic challenges due to its citizens’ low fertility rates and the fact that it has one of the highest life expectancies in the world (84 years). Currently, 25% of the national population is over 65. This disparity is far greater in rural areas because of the migration of younger generations to Tokyo and other cities, a process which accelerated after the 1970s. The Echigo-Tsumari region typifies this trend. Many homes in the area that housed three generations prior to World War II are empty (called Akiya), or have only one or two older residents. Many schools have endured a dwindling of their population until they were forced to close, and stand as vacant reminders of the villages’ predicament.

ETAT set itself a huge task: to rejuvenate the region and to restore a sense of the value of a means of agrarian livelihood in a rapidly urbanising society. What has preoccupied me most following my field trip is the very miracle of ETAT’s continuation over 15 years and, more foundationally, what it actually is. Even though it shares common ground with other major events in the global art calendar, ETAT sets itself apart thanks to its duration, its distributed character, and its location of works in areas that are difficult to access, in order to draw visitors to places they would otherwise have no reason to visit. Further, it is a humanitarian and indeed socialist response to a social crisis that, while being localised, is emblematic of the failures of Japan’s modernisation. Simply put, ETAT is a repudiation of the rationalist logic of capitalism, and of the damage it does both to the environment, and to ways of life that run counter to the drive for efficiency and profit. As the Triennale’s founder and General Director Fram Kitagawa writes, ‘A society where marginal, vulnerable and unproductive people do not have the prospect of leading a lively life is not a humane society’ (“An encounter” 9).

Much more could be said about the critical idealism that underpins ETAT, and I will return to Kitagawa’s aspirations in my concluding remarks. For now, it is important to take a realistic view of the stakes involved in investing that ethos in hundreds of discrete socially engaged art projects that have been brought to local publics in the Echigo-Tsumari region. While mixed, these publics are predominantly composed of farmers; they are people who are often conservative and nationalist in outlook, who haven’t attended university but are learned in other ways, and who often hold quite dogmatic views about how life should be lived. Not only do their values and priorities differ greatly from those of city residents, but the world of contemporary art was utterly foreign to them when the Triennale was initiated in 2000. It took years of persuasion on the part of Fram Kitagawa and his collaborators3 before local governments endorsed and supported the event within the region, and many local people were hostile to the idea. Kitagawa attributes the softening of this attitude among many (but not all) residents from one Triennale to the next to the Kohebi (little snakes) volunteers. These were young students from the city who went door to door to explain the vision of the festival, and who bore the brunt of local people’s aversion to the project. He sees these moments of conflict between people ‘so completely opposed in experience’ as having been essential to the Triennale’s success (Tsubioke). This judgement tells us something very important about the social reverberations of art that bridges the divide between the art world and the non-art literate public—something that is certainly pertinent to the themes explored below.

The extraordinary ordinary

The issues explored here cluster around the idea of the ‘extraordinary ordinary’ and ‘the extraordinary made ordinary’. These ideas came to me early on in the fieldtrip, and I have played with them in my thoughts ever since. They convey something about the opposition of art and everyday life that has dominated most western modern and contemporary art, an opposition that seemed to be totally destabilised at Echigo-Tsumari.4 To begin with, artworks that would have appeared monumental in a museum or even an urban setting are cut down to size by the visual and visceral intensity of their environments: the mountains, the geometry of the rice fields, the luminous greens, the insects and the sweat on one’s skin. These artworks are immensely vulnerable to that environment and the snow in particular, and are reliant on the vigilance and protective work of local men and women. A more compelling truth was that art was being appropriated by non-artists to serve quite particular local needs, and this extended to these practices of preservation. As Miyu, a teacher and grandmother who has had a long and pro-active association with the Triennale, explained:

The artworks themselves... some of them are fascinating and we are moved by them while others are beyond our comprehension and we don’t understand the point of making them. So it’s mixed. Not all are good. Some of them are annoying. But for us, the point is not having art here or in finding the meaning of the artworks themselves, but having different kinds of communication being born through the artworks. (Miyu, Matsudai).

Miyu’s perspective on the art’s meaning was echoed by many other people with whom I spoke or had the opportunity to listen to. One conversation I won’t forget took place in the Gejo district, when village leader Kaoru Murayama was asked by another English speaking academic (with the assistance of an interpreter) ‘what makes a great piece of public art’? Kaoru Murayama responded with a gentle laugh: ‘I leave the interpretation of the art to other people’. What I learnt from him and from others was that art was being adopted and cared for because it stimulated engagements between residents in the villages; because it promised to attract domestic migrants to the area, and because it helped to rekindle collective, ritualised practices that were formerly part of ordinary life. Thus the artworks had quotidian lives and legacies that were as important as their creative ones.

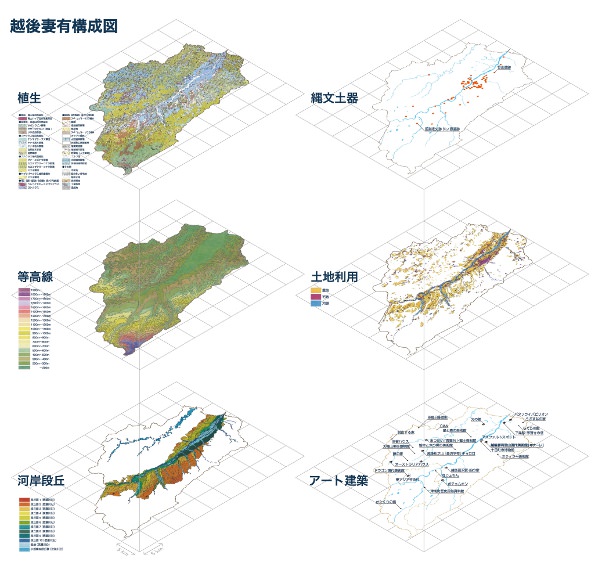

Welcome to the land of humans: Satoyama

The idea of the ‘extraordinary ordinary’ was first prompted by my early visit to the Satoyama Museum of Art/KINARE in Tokamachi, the largest town in the region and a major hub of the Triennale. At the entrance to the museum is a wall panel displaying a series of elevation maps that portray a layered landscape (see Figure 4. In the museum an English panel was beside the Japanese panel). If read as two columns, from top to bottom, the diagrams on the left show Vegetation, Contours and River terraces, while those on the right show the earthenware production of the Jomon period (approximately 10,000 – 300BC), Land Use practices and finally, Art and Architecture. The text in the top left corner translates as ‘Welcome to the land of humans’.

Figure 4: ‘Welcome to the land of humans’, wall text, Satoyama Museum of Art/KINARE, Tokamachi (2015). Reproduced with permission from Art Front Gallery.

Adjacent to the panels is some wall text, in which the concluding passage in the English version states:

The entire region of Echigo-Tsumari is a wonderland where people live and a new type of museum. Satoyama Museum of Contemporary Art was created as a gate to the journey around Echigo-Tsumari.

Welcome to the Land of Humans.

I was immediately struck by the final statement. It is a phrase akin to what one might hear at the beginning of a wildlife documentary: ‘welcome to the land of the snow leopard,’ and I read it as a kind of inversion of the anthropomorphic. It is, of course, another way of saying ‘humans are part of nature’ and specifically a way of characterising the Echigo Tsumari region as a Satoyama environment. That is to say, it is an environment that has been shaped by and reliant upon human use for 1,500 years, and an environment in which there is no clear differentiation between forest and agriculture.5 The phenomenon of Satoyama—as both a fragile reality and a paragon of environmentalist living—is the ethical and philosophical touchstone of the Triennale. As I came to understand, Satoyama is manifest in the small rice fields dotted across the flanks of the mountains and sustained through the redirection of watercourses to create hundreds of irrigation tunnels called mabu. It is also manifest in the use of leaves and humus from the forests as fertilizer, the collection of wood and grasses to construct houses and woven objects, the use of soil to create pottery, and the practice of foraging for herbal medicines and foods such as mushrooms and bamboo shoots. As Monsma summarises ‘satoyama ecology, diversity and resilience is a function of purposeful and thoughtful human intervention and maintenance’ (Monsma 38).

The words ‘Welcome to the Land of Humans’ and the portrayal of the Echigo-Tsumari region as a ‘wonderland where people live and a new type of museum’ still plays on my mind. While the region has indeed become a kind of open-air art museum and Satoyama landscapes are distinctive, I can’t help interpreting these words as an invitation to discover a very particular kind of human in their endangered habitat. Is this really a journey an enlightened art tourist should take?

Remarkably, on the second last day of my trip I received a revelatory interpretation of these words while interviewing Miyu, quoted above. This interview came about because my interpreter and I were walking past a little shop in the small town of Matsudai, in which three women sat chatting and drinking tea. The shop was selling small sewn items, pressed flower cards and bookmarks, woven sandals and pieces of pretty fabric. The women welcome us warmly and agree to be interviewed together. I learned that Miyu had played a leading role as a host to artists and coordinator of ETAT projects in the local area. Having noticed that they are also selling vegetables piled up in a basket, I speak of my admiration for the vegetable gardens in Matsudai, which were truly abundant: every home is adjoined by a large plot of cucumbers, tomatoes, beans, watermelons and herbs. I explain that I wish we had a stronger culture of growing vegetables in Australia’s suburbs, and that the ones I see here are beautiful: ‘for me it’s like an artwork!’. Miyu responds confidently: ‘here, everything is art’:

The Art Triennale is like an all field museum. Fields are part of the museum and people are exhibits. Yes, that’s right. There is that meaning too. In short, people like an old woman with bent back and an old man working in the field are part of art. So here is an artwork and an old person is working in the rice paddy there and there is scenery. The whole thing is art.

I fumble my way through the following comment:

Because I come from the city, you know, there’s a-, um, nostalgia – what’s the word for nostalgia?’ (all three women and the interpreter laugh together, fully aware of the meaning of that term). But I feel sometimes uncomfortable about the way I think about it because I don’t want you to be- ah, I don’t want to treat someone else like they are an exhibit!

At that moment Miyu spots something and draws me to the shop entrance to look out to the street while talking, and my interpreter laughs as she translates, ‘here you can see another exhibit!’ Miyo points to an elderly lady making her way slowly down the road leaning on her metal frame. There is more laughter as we return to the table, though I am a little worried that I have been party to a slightly crass act. The conversation changes course because Miyu has to depart with her granddaughter. But I am left with the impression that Miyu has an assured knowledge of the mix of elements that are the subject of outsiders’ interest, and that this is acceptable. It makes sense to her that the art, the environment, and the people should together comprise this exceptional ‘museum’. Her words help me to recognise that many local people have a strong reflexive awareness of the beauty and tragedy of their ‘ordinary’, and that this underlies both the vulnerability and the attractiveness of their communities. It is also clear that the Triennale has played no small part in building this reflexivity. As Hokata, a young man who moved to the area with his partner from a nearby town and runs a local hotel relates:

I think by allowing the installation of the artwork, locals saw their place from a new perspective and re-discovered it... They realize that although to local people it’s an ordinary scene and nothing extraordinary, to city people, it is very valuable. That realization makes local people feel proud. It has an effect of re-affirming their life.

Most of the people I spoke to saw their regional home as being distinguished by the extreme snow in the winter—which regularly reaches several metres high and half buries their houses—the beauty of the mountains, the close-knit character of their communities and the absence of children and young people. Whatever valuable qualities life in the region possesses, and however much technology has been adapted to people’s needs and wants (central heating, pesticides, cold drink machines), it is a hard life. Rice farming is particularly strenuous physical work, and mere survival from one winter to the next requires skill, willpower and strong filial and community bonds. The challenge of withstanding the winters is here described by Arisu, another of the three women I interviewed in the Matsudai shop:

During winter, we cannot leave the house unless we remove the snow in front of it. Removing snow in front of our house gets more difficult as you get older. It requires real efforts. So when people get older and start living alone, they tend to go and live with their [children]. Even if they don’t want to, the reality is that they have no other choice but to go to live with their children in the city. If we had no snow or less snow, we could manage ourselves but we have too much snow (Arisu, Matsudai).

As well as hearing about the snow, learning of people’s concerns about the region’s diminishing population cut through the seduction of only seeing ETAT as a vibrant, participatory art festival in an exotic location. I was certainly brought to earth by the conversation I had with Haruto from the community of Hachi (which has a population of 100 people), a young salesman of few words volunteering at an art site on his day off:

LF: What are your hopes for the future for this area?

Haruto: For the future? Well the population is shrinking so I hope we can increase it somehow. With a decreasing population, the community is going to disappear. With events like this, various people get involved in art and just being here [in this event] will help increase the population. … People outside bring in new blood and some volunteers end up getting married here and having kids and living here.

…

LF: Do you take a strong interest in the artworks themselves, will you travel around, with the guide book, and see all of the Echigo Tsumari Art field?

Haruto: Myself? [He looks slightly incredulous] No I haven’t.

LF: So art is not something you have that much interest in?

Haruto: No it’s not.

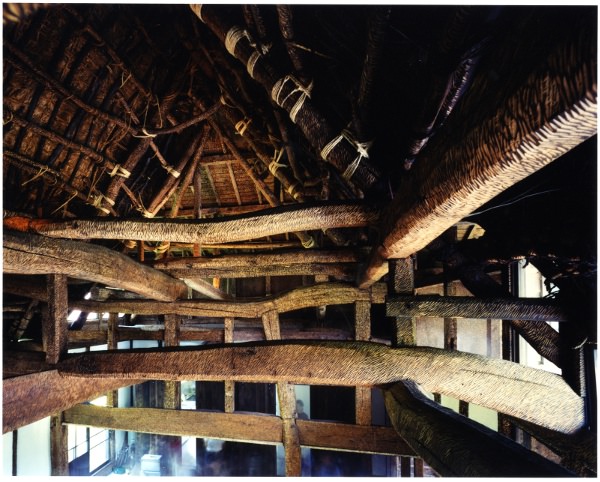

The labour of the body, the labour of the hand

The idea of the ‘extraordinary ordinary’ also crystallised around the conspicuousness of work: the labour of the body, the labour of the hand. It was, of course, striking to see men and women in their old age tending to rice fields and vegetable gardens, and I thought a lot about the relationship between time, labour and subsistence that it exemplified. It was also obvious that ETAT makes an aesthetic virtue of physical work and craftspersonship: there was a preponderance of art pieces whose very materiality and sensuousness manifests labour: crafted objects, sculpture, timber constructions, plantings, and works made of soil, clay, wood, fabric and straw. As such they were reminders of Satoyama occupations and the fact that the entire region, even its apparently ‘wild’ spaces, has been shaped by human labour. At the same time, many socially engaged artists who have participated in the festival have harnessed traditions of making, and making together, during their residencies in the region. Sometimes this collaboration is planned, sometimes improvised: in a few cases local people became engaged with the Triennale because of a compulsion to assist an artist they observed struggling to build or install an artwork outdoors (Kitagawa "Linking the World with the Uniqueness of Echigo-Tsumari" 12; Kitagawa Art Place Japan 177). As Traphagan has written in her ethnography Ritual, Well-Being, and Aging in Rural Japan, there is a strong moral dimension to working hard and having little idle leisure time for older generations. This stems in part from the food shortages and poverty experienced during and following World War II, but it also derives from a particular ethic around ‘aging well’: warding off senility through continued physical activity and social engagement, and serving the collective wellbeing of family and community through caretaking roles.

The agrarian work ethic was wondrously incorporated in one of the most iconic permanent artworks at ETAT: The Shedding House. This work was created by restoring a minka (a traditional house) in Hoshitoge that was over 200 years old and had been left unoccupied for several years. Between 2004 and 2006 Junichi Kurakake, a sculptor and teacher at Nihon University in Tokyo, led teams of students to carve every interior surface of this minka with a simple motif. The pervasive tactility of the house lends it an aura of warmth that is hard to explain.

Figure 5: Juniche Kurakake and Nihon University College of Art Sculpture Course ‘Shedding House’ (2012). Photo: Laura Fisher

Figure 6: Juniche Kurakake and Nihon University College of Art Sculpture Course ‘Shedding House’ (2012). Photo: Juniche Kurakake

As Kurakake told me:

The fact is life here involves very day-to-day activities that may be unexciting. Terraced rice fields are the same. They are made by people, aren’t they? If I wanted to create something better than terraced rice fields, I thought I needed to create art through labour, day-to-day labour. The Shedding House was born out of these ideas.

Kurakake is involved with several other projects at the Triennale and spends extended periods in the region participating in other aspects of village life, including rice planting. I asked whether the students do so as well:

JK: I get them to do three patches of paddies in 2 hours and then get them go back to work (carving). It’s hard work to keep going so we invite a DJ to the rice paddy, invite a singer there and play classical music with a trumpet…

LF: To entertain while everyone is working?

JK: Yes, I like thinking about things like this.

LF: That’s a good influence of the city to the country? (we are laughing) It’s a different way to do things?

JK: They laughed. But the local older men joined in the dancing. Once we are able do things like that quite naturally, the differences between the country and Tokyo disappear.

Here Kurakake alludes to the challenge involved in establishing bonds between the young from the city and the old from the village, having also told me about moments when local people were prejudiced against his students.

It is worthwhile returning to Traphagan again for insights into how collective art production becomes locally meaningful and consequential at ETAT. Traphagan makes the point that the rituals, ceremonies and festivals that are customary to rural Japan are only tangentially about religion. Rather, they are about the qualities of ‘interdependence and reciprocity that shape Japanese ideas around human relationships,’ and the belief that the regular enactment of ritual—particularly by the elderly—is vital to collective wellbeing (Traphagan 27). I quote from Miyu again:

The fact that the festival is well grounded in the community is because locals are repairing, protecting and maintaining them (the artworks) with their own efforts. Providing that sort of local support has become our activities in the area. People in the village are deeply involved and as you mentioned connections, the festival created not only connections and communication between the locals and artists but also within (among) the locals. Even young people who were previously not involved come out and participate in the process of creating artworks. That creates opportunities for communication between the young and the old (Miyu, Matsudai).

Miyu’s words attest to ETAT’s reliance on local volunteer labour for the artworks to survive. But they also attest to the fact that these habits of care are perpetuated because they have been anchored to a very local sphere of value, and a very local understanding of how individuals can survive the social crisis of depopulation.

The most affecting description of the labour involved in caring for artworks was provided not by an older local, but by Hokata, the young hotelier who moved to the region a few years ago with his partner and with whom he now has a small family. Hokata had grown up in a town south of the region and studied art at university. His curiosity about nature and conviction that his artistic work required him to be immersed within nature inspired him to move to the mountains, and he has managed the hotel since 2010. In the winter he is part of a team of young people who work daily to remove snow from houses that are now permanent installations for the festival. This is vital work: these houses contain some of the most valuable installations created by esteemed international artists, and if the snow wasn’t removed, the roofs would cave in.

Figure 7: Snow removal in winter 2015, roof of ‘Doctor’s House’, Lee Bul/Studio Lee Bul. Photo: Akiko Tobita.

LF: ‘...do you find the snow hard, do you get depressed, or are you still happy you made the decision to come to the mountains?’

Hokata: Well, when winter comes, I feel depressed. Because my work also involves removing the snow. I do snow removal for work. So before work I remove snow at home. After work, I remove snow again. It sometimes makes me wonder why I came here…

LF: So it means then that your winter—your winter is just as busy as your summer, but for a different reason?

Hokata: Yes it is. I feel gloomy during winter... Because we no longer have the sun. I have to scrape the snow off every single day in that environment. It feels a little like being bullied.

LF: A bully—bullied by the snow.

Hokata: Yes, as soon as I remove it, it falls again.

LF: I still want to visit!

Hokata: Yes, please do. It’s interesting. The scenery is completely different.

It is these stories which most disturbed my sense of the relationship between the ordinary and the extraordinary, between art-as-exceptional and the mundane. What good is it having permanent installations by artists like Marina Abramovic, James Turrell or Lee Bul, attracting visitors from all over the world, if the rooves cave in? These are precisely the kinds of installations the snow removal team are protecting. I felt I was hearing the naked voice of art’s humility when listening to Hokata, Miyu and others who spoke of the care of artworks. Here the tasks that museums assign to conservators and technical staff, and which conventionally take place beyond the gaze of art audiences, are raw, burdensome and socially meaningful. And at the same time Miyu’s description—like Haruto’s blunt words above—conveys that local people are not necessarily invested in the Triennale because they admire the artworks as such, but because of the social relations they mediate. I was struck by the emphasis she and others placed on internal communication, rather than communication with outsiders. As another community leader—Jiro—described to me, the presence of art has created an imperative for bringing isolated elderly people out of their homes to reconnect with each other in the village. Here Traphagan’s remarks on the importance of customs that nourish reciprocity and interconnectedness ring very true.

Concluding thoughts

Upon my return to Sydney, I deepened my research into the biography of ETAT’s founder, Fram Kitagawa, and learnt more about the source of his socialist and environmentalist beliefs (Monsma; Matsuo; Kitagawa Art Place Japan). I came to understand that while Kitagawa seeks to harness the utopianism that can be invested in art, he aspires to the diminution of the exalted art object and the elevation of vernacular culture. As Matsuo writes, this disposition reflects a ‘commitment to a populist sense of community with one foot planted in activism and the other in art’. For example, Kitagawa laments the fact that Japanese forms of culture like festivals, gardens, the culinary arts, ikebana and the domestic tokonoma alcove were devalued in favour of Western notions of art following the Meiji Restoration. These practices are anchored to the distinctive Japanese aesthetic of wabi-sabi, which revolves around transience and simplicity. These forms are offered an honoured platform within the ETAT. As Kitagawa states, ‘[p]erhaps there are aspects of the Echigo Tsumari Art Triennale involving popular art and living art that may be uncomfortable to the sensibilities of the fine-art purists. But Echigo-Tsumari deliberately aligns itself with an approach that serves the public and incorporates art into life’ (Kitagawa Art Place Japan 224; Tsubioke). I also learnt of his admiration for Christo and Antonio Gaudi. He holds Christo in high esteem because his work has ‘a sense of matsuri, or festivity’ (Kitagawa Art Place Japan 26). In the case of Gaudi, Kitagawa is inspired by his socialist orientation and rough craftsmanship and attributes to Gaudi his sense that art’s power is inescapably limited by geography: ‘reality cannot be separated from region or place, and [I] see anything else as being simply in the realm of fashion. So I believe that finding things that can be done in a specific region or community…is what leads to solid gains and results, even if they would be small’ (Tsubioke).

These remarks only skim the surface of Kitagawa’s thought, but they—and the interviews discussed here—point to a vital truth. Our acceptance of art’s extraordinariness is what licenses artists to do odd and fantastic things, however, the historical process by which we institutionalised that status had the effect of displacing creativity from the everyday. In essence, ETAT is a benevolent and audacious experiment in returning art to the people. Its resolutely local orientation allows it to draw out the threads of everyday aesthetics that persist in rural Japanese society, reminding us that while socially engaged art is a field of contemporary creative practice, it is also very old. What continues to preoccupy me following these conversations in the field is that, by situating art within social scenarios in which engagement arises from a sharp pragmatism born of a slow social crisis, and in which the artworks are appropriated through labour and care to nourish social bonds, ETAT exposes art to a kind of devolution in status. It thus exemplifies that perhaps insoluble predicament of socially engaged art, whereby its meaningfulness cannot always be recouped by the institutions and discourses that customarily define art’s value.

The author wishes to thank all of the individuals who agreed to be interviewed about ETAT, Miyoko Shibata for her stellar work as interpreter, Juniche Kurakake and Rei Maeda for assistance with images, and the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful feedback. This project was assisted by Sydney College of the Arts, the Visual Arts Faculty of the University of Sydney.

Works Cited

Fisher, Deborah, et al. "What Is the Effectiveness of Socially Engaged Art." 2013. A Blade of Grass, September 2013. Web. 11 October 2015. <http://www.abladeofgrass.org/blog/ablog/2013/sep/18/growing-dialogue-what-effectiveness-socially-engag/>.

Gammage, Bill. The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines Made Australia. Crows Nest, N.S.W.: Allen and Unwin, 2012. Print.

Helguera, Pablo. Education for Socially Engaged Art. New York: Jorge Pinto Books, 2011. Print.

Hirschhorn, Thomas. "Gramsci Monument." Rethinking Marxism 27.2 (2015): 213-40. Print.

Jackson, Shannon. Social Works: Performing Art, Supporting Publics. New York and London: Routledge, 2011. Print.

Kester, Grant H. Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press, 2004. Print.

Kitagawa, Fram. Art Place Japan. New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2015. Print. ---. "Linking the World with the Uniqueness of Echigo-Tsumari." Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennial 2009. Niigata: NPO Echigo-Tsumari Satoyama Collaborative Organisation, 2009. Print.

Kobori, Hiromi, and Richard B. Primack. "Participatory Conservation Approaches for Satoyama, the Traditional Forest and Agricultural Landscape of Japan." AMBIO: A Journal of the Human Environment 32.4 (2003): 307-11. Print.

Matsuo, Amiko. "The Optimistic Vision of Kitagawa Fram and the Echigo-Tsumari Art Triennale." Kyoto Journal 82 (2015): 1-10. Print.

Monsma, Brad. "Echigo-Tsumari and the Future of Satoyama." Kyoto Journal 82 (2015): 31-43. Print.

Thompson, Nato, ed. Living as Form: Socially Engaged Art from 1991-2011. New York: Creative Time Books, 2012. Print.

Tiampo, Ming. "Gutai Chain: The Collective Spirit of Individualism." positions 21.2 (2013): 383-415. Print.

Traphagan, John W. The Practice of Concern: Ritual, Well-Being, and Aging in Rural Japan. Durham, N.C: Carolina Academic Press, 2004. Print.

Tsubioke, Eiko. "Presenter Interview: Art Bringing Hope to Echigo-Tsumari - the Ongoing Journey of Fram Kitagawa." Performing Arts Network Japan, 2009. Web. 9 December 2015. <http://www.performingarts.jp/E/pre_interview/0907/1.html>.

Footnotes

- For a useful, informal discussion of this issue see Fisher et al, 2013. For other useful literature on socially engaged art, see Grant Kester’s Conversation Pieces, the volume Living as Form edited by Nato Thompson, and Shannon Jackson’s Social Works.↩

- With the exception of Junichi Kurakake, I have used false names for the people I interviewed at their request or with their permission.↩

- Kitagawa’s endeavours have been significantly supported by many others, including Rei Maeda and other staff at Art Front Gallery, founded in 1984, which is the engine behind ETAT.↩

- This opposition has of course been destabilised by a range of artists since the mid twentieth century, with Marcel Duchamp, Allan Kaprow, Mierle Laderman Ukeles and the Fluxus artists being among the most influential practitioners in the west. These artists eschewed the institutional and market structures that sustained art for art’s sake, and in some cases confronted the social inequalities that were implicated in how art was configured. In Japan the post-World War II Gutai movement, led by artists Yoshihara Jirō and Shimamoto Shōzō, similarly sought to radicalise Japanese art by locating creativity in the sphere of the body rather than the art object. As Tiampo writes, the Gutai movement was also an ethical response to the Japanese people’s identification with the fascist leadership during the war. Experimenting with physicality in the public domain was viewed by the artists as a means to galvanise individual agency and instantiate a post-feudal sense of community premised on collective freedom and heterogeneity.↩

- Sato means “village” and yama means “mountains”. Satoyama landscapes become less healthy without human use, a condition akin to that of Australian bushland in the absence of Indigenous firestick farming (Kobori and Primack; Gammage; Monsma).↩