Feral trade: taking back markets for people and the planet

by Katherine Gibson and Kate Rich

- View Kate Rich's Biography

Kate Rich is an artist currently based in Bristol, United Kingdom.

- View Katherine Gibson's Biography

Professor Katherine Gibson is a researcher at the Institute for Culture and Society, University of Western Sydney.

Feral trade: taking back markets for people and the planet

KATHERINE GIBSON and KATE RICH

People all around the world are experimenting with making and shaping a different kind of economy, one in which our roles are not limited to those of self-interested consumer, employer, employee or investor, one in which we are not just cogs in a voracious growth machine driven by the demands of the market. In daily life we all occupy multiple economic roles that contribute to well-being—we gift, volunteer, care, share and cooperate in households, communities, associations, cooperatives, social enterprises and socially responsible corporations. We forge interconnection around ethical concerns of how to live well, how to respect others, how to steward our environment.

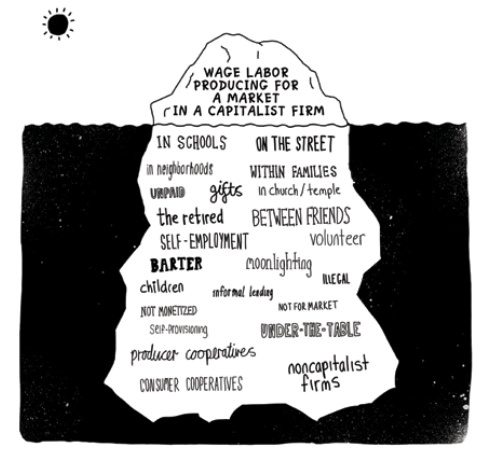

Not much is known about the diverse economy that supports life, as most economic knowledge focuses only on what constitutes a ‘capitalist economy’—wage labour and production of commodities for mainstream market exchange. This is just what appears above the waterline of the economic iceberg.

To take back the economy as a site of ethical interaction and thus greater social and environmental well-being, J.K. Gibson-Graham have proposed a post-capitalist politics of language, a politics of the subject and a politics of collective action (see Gibson-Graham 1996, 2006, and Gibson-Graham, Cameron and Healy 2013). When economic geographer Katherine Gibson met artist and entrepreneur Kate Rich earlier this year she discovered someone who was practicing all three politics in her fascinating practice of ‘feral trade’. She also learnt of some new strategies for building extended, international scale community economies.

What follows are extracts from a conversation between Katherine and Kate that show how one woman can take back the faceless market and render it a transactional space of ethical encounter.

A POLITICS OF LANGUAGE

KATHERINE: I was fascinated to come across Feral Trade, your international exchange network/action/art practice and am interested in what you mean by the term 'feral'?

KATE: The definition I have been using is “wilfully wild” as in pigeon, as opposed to romantically or nature-wild like “wolf”. This is largely to explain it to second language English speakers, who generally are not familiar with the word “feral”, I realised after I named it that the word feral is actually barely used outside Australia. In America they roll it round their tongues like it’s a new candy they are benevolently trying out. FARERRAL?

The pigeon/wolf benchmark is to establish the case for a kind of opportunistic, scruffy, street mode of international trade, able to thrive in any environment provided, as opposed to reviving some folkloric, silk road notion of the noble trader. Pigeons are very DIY. It is also a maybe irritated reaction to the monopolisation of contemporary trade models by empty and contestable words like “free” and “fair”.

Feral Trade coffee to Bern

KATHERINE: Are there other aspects of the pigeonliness of pigeons that are relevant here, that is, besides their DIY-ness?

KATE: It is also specifically the way pigeon behaviour is perceived and represented: feral animals being calculatedly wild just to mess with humans. Knowingly-wild, as opposed to the wonder through which the antics of harp seals or other somehow nature-wild citizens of the animal world are observed. I would relate this to the larger problem of segregations in general, wild/nature existing away from humans, in the same way as slow/local/organic/fair trade are somehow cordoned off into their own pure, and by that definition completely limited categorisations. The idea that they are somehow not intricately intertwined with socialness and the other mess of life. Whereas the pigeon clearly crosses that cordon, it eats the same food as us, “steals” our food in fact, “trespasses” on our architecture, as a global citizen happily turns up at all our international travel destinations.

A POLITICS OF THE SUBJECT

KATHERINE: There are many people around the world involved in fair trade networks because they are committed to a more ethical interchange with producers and environments where their food and other consumption items are made. What are your views on existing fair trade networks?

KATE: Fair trade is perhaps necessary but I think points more to the problems than the solutions. It has been damned as “business as usual” (some of the objections have been set out in Andrew Chambers’ article). Recent studies suggest it is failing even on its own terms (see, e.g., the FTEPR).

For me, the immediate objection to the fair trade label is its taking up the word “fair”, it’s an ambitious truth claim. There is a lot to say about the structure of the industry but you can also look at it just from the perspective of the packaging.

With fair trade coffee you probably see a picture of the farmer on the pack, holding up the product and smiling, alongside a testimonial that he uses the money for his children’s education. Compare that with going to your local farmers market or the corner shop. When you make a purchase do you check—“so young man, will you use this money for your children’s education?”—it’s a queasy demand. At the same time the fair trade farmer has no way to interrogate me on where I got my money from and make a moral judgement on that. Plus on the coffee packet I can see the (supposed) farmer but he/she can't see me, so even at this level the word “fair” is a bit of a stretch. (“Equal Exchange” is another big brand in the US). What this packaging does is, I would say, wilfully obscure pretty much the whole food chain, the reality of supply, in return for a quick fix of happy-farmer-love—and understandably most of us don't have time at the supermarket to think any of this through. If this is necessary I think it is unbelieveably limited in its ambitions, compared to the kinds of expansive networked relations we could be creating through food. In these times of facebook etc., when we are being sold into seeing our social relationships as products, treating products primarily in terms of relationships is a potentially exciting inversion.

KATHERINE: You are pointing to an ethical interchange that goes both ways between producers and consumers, and perhaps starts to shift the identity of each. Do you think that Feral Trade breaks down the producer/consumer binary?

KATE: It’s a process of conversion. I don't use the word consumer—my system has senders, carriers and receivers, more like email, and often interchangeable. With Feral Trade the receiver is not always or simply defined by consumption (or choice). They are generally involved in the manual chain of supply, often having to go and meet someone to receive their product, or else they might upload a delivery photo and report that the supplier can then see, or they courier part of their shipment onward to someone else. In terms of network structure all agents in my network are active nodes, capable of sending, receiving or forwarding information - or in this case groceries - although some are more active than others.

A POLITICS OF COLLECTIVE ACTION

KATHERINE: How did Feral Trade start and how does it work?

KATE: I started it in Bristol in 2003 to solve a practical problem, how to find a reliable source of coffee for the Cube Microplex, an independent art space where I was working as volunteer bar manager. To avoid the fair trade moral honey trap I decided to import the coffee myself. I also wanted to test the load-bearing capacity of email as a kind of media-art stunt, to see if I could source and ship an international commodity—coffee is the second largest traded commodity after oil, supposedly—using just my network connections. In part it was a personal mission, to unpick for myself how the global food commodity market works, by entering it as a sole trader.

As Feral Trade runs now, I describe it as an underground freight network at least as reliable as DHL, through which I am able to run a grocery business sourcing and delivering food items - coffee, tea, oil, salt, corn, grappa, chocolate - worldwide. All my suppliers and all of my customers are either friends or friends of friends, or their parents, neighbours, colleagues etc. The business is small scale, which is what extended social networks logically are. Every delivery is logged on the Feral Trade Courier website at http://feraltrade.org, an online non shop where you can see everyone else's deliveries but you can't actually buy anything. You can also possibly see the farmer but s/he can also see you.

Almost all of the shipping and distribution is done in the spare baggage space of existing journeys—friends and acquaintances travelling for mostly either diasporic reasons or for work. I am particularly interested in harnessing the surplus hot air of the art world as a freight resource, so other artists, curators and cultural organisations often act as couriers and depots.

KATHERINE: Do you ever get any feedback from your “carrier pigeons” including those who didn't know the term feral before?

KATE: The couriers are all invited to report their journeys in the online database. However, interestingly, it’s much easier to get someone to carry 10 bags of coffee across Europe and hand it on to a stranger, than to upload a one line report! But if you scan through all the deliveries online, occasionally you can see some comments.

Overall people get the idea, it doesn't need much explaining. I think that parcel-carrying is quite intuitive human behaviour that has been only recently bleached out of the system by excessive regulation and corporate intervention. So generally people are quite comfortable with reverting to it.

COMMUNITY ECONOMY ACCOUNTING: TRACING ETHICAL ENCOUNTERS

KATHERINE: The labels on your feral trade coffee are particularly interesting as they record all the transactions that have occurred along the “supply chain” including the actual monetary amounts involved. How do you collect this information and why do you do it?

Heath Bunting's coffee courier briefcase

KATE: The Shipping Facts labels are generated as each product comes in. They show the import itinerary of the product by compiling a list of all direct expenses of procurement. The labels total up the “cost” both individually (your particular bag of coffee) and communally (total paid for a 350kg shipment of green coffee beans from Mexico). So you can see that for your particular 500g bag of beans that £2.72 went to the farmer, £1.34 on sea cargo—down to the fractional costs of the currency transfer, port charges, customs fees etc. It’s a way of opening up the food chain, the full ecology of supply, beyond just the fetish of the farmer.

KATHERINE: What is the most unusual route that products have travelled to get from their producer to their final consumer?

KATE: Products often travel in hops, stored en route at friendly depots such as art organisations or sometimes peoples’ homes or offices or at hotel reception. The ones I find most interesting have gone in loops, which is the inverse of the brute accounting of air miles, for example they might pass through the same airport or railway station twice as they catch onward rides with different travellers.

Recently I bought some Mexican blue corn which travelled from halfway up a volcano in Mexico via Mexico City to Łódź in Poland, where it took several weeks to transit to Warsaw and then eventually flew to England with someone else's Polish friend who was attending a work conference for a cosmetics company on the outskirts of London. She left it in a plastic bag at the Holiday Inn reception, in Epsom where they run the Derby, I had to walk across the racecourse to get there. The Holiday Inn receptionist handed over the plastic bag which had my name stapled onto it, totally incurious. I took the corn to Bristol, then later travelled with it back through London and up to the east coast of Scotland where it was made into tortillas at an arts centre garden party. See http://feraltrade.org/shipment/FER-1725

EXTENDING and RESHAPING ENCOUNTERS IN AN INTERNATIONAL COMMUNITY ECONOMY

KATHERINE: how has Feral Trade opened up or changed your relations to food, the art world and the economy?

KATE: As a person/eater the project has been a very actual way to unravel the mysteries of food supply by physically entering that landscape as a trader. To learn that coffee has a season, that you import green beans then they lose 20% of their weight on roasting (you are shipping 20% water!), plus all the frictions that the supposedly smooth passage of goods exerts. Trading direct with producers internationally has also been a way to understand how current quite constrained ideas of slow food or local food can be stretched into other territories.

For art, it has enabled me to think about the art world as a productive carrier for other activities. You can look at it in terms of the excesses, the many art air miles flown by practitioners and visitors as destructive behaviour built in to the system. But when an artist employed by whatever museum or biennial agrees to carry a package intercity and hand it on to someone there, it's a great way of hitchhiking on that industry, using it to generate other communications and goods.

With respect to economics, Feral Trade is the first staging for me in a long term study of economics. My first question was very literal, coming from a position of no economics education - and my theory on this is that this is where the power elite of society diverges, they are imprinted early on with the basics of finance and economics, which self-fulfillingly is also why economics is privileged over for example ecology or anthropology or even science as the governing discipline of world society. So my first question as a complete amateur was, what is a commodity? (And how could that be different?). Feral Trade is fundamentally a way of explaining that to myself.

WILFULLY WILD, OR BUSINESS BY OTHER MEANS THAN THE “NATURALLY” WILD OPEN MARKET

Kate’s practice embodies a determination to question the impersonal, unethical and exploitative practices of trade. In the “wild open market” transactions are bleached of human connection. The price-setting mechanisms of consumption items are hidden and coolly detached from any ethic of interconnection. Subservience to the wild free market is both idolized and naturalized. But, as Kate shows we can opt to be wilfully wild and construct our own DIY trading systems.

Feral Trade is forging innovations that strengthen community economies worldwide. Through extension and cross-appropriation she is showing how principles of the slow food and local food movement can be stretched out over space via trade that honours not only provenance but the face to face transaction and attention to the fairness of every transaction along the supply chain.

By harnessing excess she is using underutilized space that moves around the international art world—“subsistence product” hitch-hiking on art product and people transport.

By rendering interconnection visible, her product labels document every monetary transaction between producer and final consumer, including not only the amounts paid but the material conditions under which losses or gains are made for seller and buyer, thus ensuring that we have access to knowledge about our interconnections with distant others.

As she transitions between the realms of art and business Kate Rich’s “self-directed study of economics” signals the potential of feral-ity as a different way of being and surviving together.

WORKS CITED

Chambers, Andrew. “Not so fair trade”. The Guardian. Sunday 13 December 2009. At http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/cif-green/2009/dec/12/fair-trade-fairtrade-kitkat-farmers.

Cramer, Christopher et al. Fairtrade, Employment and Poverty Reduction in Ethiopia and Uganda. 2014. At http://ftepr.org/wp-content/uploads/FTEPR-Final-Report-19-May-2014-FINAL.pdf

Gibson-Graham, J.K., J. Cameron and S. Healy. Take Back the Economy: An Ethical Guide For Transforming Our Communities. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

Gibson-Graham, J.K.. A Postcapitalist Politics. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006.

Gibson-Graham, J.K.. The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It): A Feminist Critique of Political Economy. Oxford and Cambridge, MA: Blackwell, 1996. Republished by University of Minnesota Press in 2006 with a New Introduction.