Capture

by Hester Joyce

- View Hester Joyce's Biography

Hester Joyce is an artist and academic at La Trobe University, Melbourne.

Sightlines - Filmmaking in the Academy

Title: Capture (Hester Joyce, 2013 - A/V video, 3:46 mins)

Artist: Hester Joyce, La Trobe University

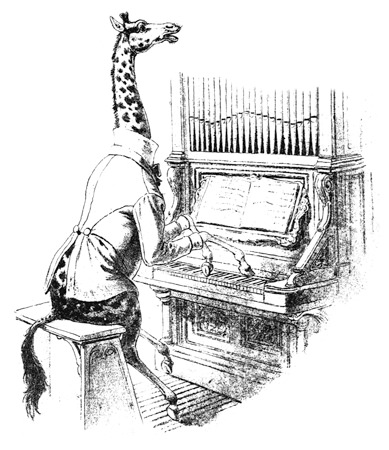

This talented Giraffe can play

This talented Giraffe can play

In such a skillful, pleasing way,

That every one who hears agrees

That he is Master of the Keys;

So 'tis not strange at all that he

Should hold his head high, as you see.

Curious Creatures Release Date: February 22, 2011 [EBook #35357]

Capture began as an exploration of representations of giraffes from a variety of positions – western, colonial, local/indigenous, enviro-art, painting, travel logs, wild imagination – stimulated by a visit to the Flat Dogs Camp South Luangwa National Park, Zambia in 2011 and then to Musée Magritte Brussels and viewing Rene Magritte’s painting, The Cut Glass Bath – of a giraffe in a cut-crystal glass as some kind of feral cocktail, legs bent and twisted like straws into the base. The glass is set within a distorted veldt-like plane. Later stimuli were a greeting card with a giraffe riding a high-wire cycle and another of a tux-wearing, honky-tonky piano player that set me wondering about the mystification and containment of wild animals. And about how they had invaded our collective imagination. Failure to domesticate these ‘giants’ has led to such representational failures to contain them.

Synopsis

An Alice in Wonderland-type girl immerses herself in Western re-imaginings of giraffes and other fetishized African animals, in books and sounds before falling into a dream that is then invaded by wild versions of those animals. There is a hunt on – a lion hunting and a giraffe striking back, and we hear tourists looking for such a kill. From her dream the girl wanders amongst her litter of toys – giraffes, elephants, hippos, zebras, leopards, lions – captured in endless versions, of wood, fabric, paper and glass. Secure in these objects she sleeps on and then returns in her dream to find her empty bed colonised by the image of a giraffe.

Capture addresses the question of ferality as a zoological phenomenon and as a critical concept in a postcolonial context. A fundamental idea is that these beasts inhabit our imaginations more vigorously than they do our waking lives. The film plays with notion that the ‘big five’ African safari animals (African elephants, leopard, rhinoceros, lion, Cape Buffalo) that were once highly prized trophy game animals are now equally prized eco-tourism sights. While giraffes, rather than being feral, are in some places endangered, giraffes are allowed to be feral in this environment, they are common not so highly prized – they are not contained nor hunted. The giraffe has become a figure of the feral in art or culture as its image infects everyday day and imagination despite, or perhaps because of, its exotic-ness. The feral invades us.

Rationale / Creative Practice

The piece uses sound/text from Rudyard Kipling’s Just So Stories, zoological descriptions from Dagg’s The Giraffe: its biology, behaviour and ecology, local tribal accounts of giraffe behaviour and vision from archival family and public footage, maps, photographs, magazines, and interviews. The method was to remix collected and found, screen and sound images of giraffes that attempt to control and contain them, creating a four minute audio-visual piece underpinned by themes of memory, place and sustainability. The piece is shaped by my experience of giraffes, from the fanciful versions of Kipling and Roald Dahl’s The Giraffe, Pelly and Me through a childhood beset with ‘wild things’, to personally collected game park footage. The sounds are a variety of voices telling tales about giraffes, fanciful and not, truthful and not.

It begins with the title Capture shedding light on a carved wooden giraffe that in turn casts its distorted shadow across a wall. Is image making a form of capture? How does this capture distort its prey? Or are we so captured by the strangeness of rift valley animals (zebras, lions, elephants…) that they become feral in our imaginations? The remixed texts are interwoven to awake us to the idea that all representations, even purported factual ones, are more or less fanciful.

Giraffes from Arabic zarāfah fast walker (Oxford English Dictionary) defy zoological descriptions from the beginnings of western categorization, in the first instance being named Giraffa camelopardalis because its skin recalled the leopard, its shape the camel and its hooves the ox. Giraffe biology contests ‘normal’, with these animals having the longest legs and neck, dangerously high blood pressure, and largest hearts of terrestrial animals, along with a rare ability to live on thorny acacia leaves. There is a mistaken belief that giraffes are quiet, passive creatures but they are, like other animals, wild and are feral in our imaginations above and beyond domestication even in ‘like-ness’. Animals that are domesticated are more easily represented as static and contained. The ‘big five’ are often pre-emptively eulogized or reduced by comedic containment.

The representation of giraffes and other animals in Capture is informed by the site and method of the collection of the footage. The day and night time safari footage involved participation in tourism – game parks are a capture of both spectator and feral spectacle. Other daytime animal footage was at Australian zoos – a more extreme kind of incarceration. It is unlikely that Western audiences will recognize the significance of the final images of one giraffe standing chewing a strand of grass while several others sit around him. This family tableaux is only possible where there are no predators and would never occur in the game park or on the veldt. Giraffes only sit to sleep for 20 minutes at a time while a sentinel keeps watch. The Flat Dogs guides would recognize this is not normal behavior. Similarly the text and audio text is fantastic stories, Western biological description, poetic memory, African guides information, live hunt description – snatched from various places – but which is true? The guides, for example, observe that giraffes are the most brotherly of animals – an idea some what contradicted by the violence of their neck fighting through which they can inflict life-threatening injuries.

Capture suggests a complicating inter-textuality where the appropriation of the wild by artists and storytellers who can never fully realize the animals becomes a personal journey where primary imaginings of childhood are seeded and are endemically feral. A child walks through her littered toys – many versions of ‘the wild’ – dwarfing them. Similarly her footsteps are imprinted across colonial and post colonial maps in a way that suggests the same kind of loss of perspective. There is consideration of the forgetting and blindness of colonization and ‘whiteness’, of indigeneity and eco-criticism that is intentional. The autobiographical aspect of the story is the organizing principle that opens up the issues that arise from the film’s cultural viewpoint – the issues around post-coloniality – about zoological phenomena – are remixed and broken and are always already – never resolved. It attempts to raise these questions about representation in a playful and visual form – to posit ideas through a flow of images and sounds rather than through a constructed argument, thus contesting standard academic rhetoric.

Works Cited

Magritte, Rene (1946), The Cut Glass Bath, last accessed 02/02/2014.

Kipling, Rudyard (2008), Just So Stories, Vintage Classics.

Dagg, Anne Innis and J Bristol Foster (1976), The Giraffe: its biology, behaviour and ecology, New York, Van Nostrand Reinhold.

Dahl, Roald (1987), The Giraffe, Pelly and Me, ill. Quentin Blake, London, Puffin.

Anonymous, The Project Gutenberg EBook of Curious Creatures, last accessed 01/12/2013.

Oxford English Dictionary online, last accessed 02/02/2014

Musée Magritte, last accessed 02/02/2014.