untamed

by Susan Silas

- View Susan Silas' Biography

Susan Silas is a visual artist working with photography, video, sculpture, post-photographic media and the printed word.

untamed

SUSAN SILAS

Video caption: Leda and the Swan, 2019. Single channel version of a five-channel video installation.

Video caption: I to Eye, 2022. Single channel version of a three-channel video installation titled the woman and the falcon.

This essay is about two video works, Leda and the Swan and I to Eye, but it is also about the progression of the works I have made with birds and how my thinking about them and my relationship to them has evolved over the course of that time. I have come to see that there are threads that hold the work I have done with birds together, but the threads are loose, and more akin to a stream of consciousness than to a theoretical construct. The arc of my work, both with and without birds, has been about embodiment and the way we think about ourselves with respect to that container which is the body. Close attention to the body began for me with photographs of piled up desiccated bodies shot in liberated concentration camps at the end of the Second World War. Those images populated my imagination as a small child. My work is also held together by my own subjectivity. That may be totally obvious, but my focus on the self and what a self is and the inclusion of my own body in much of the work, is inherent to how it has grown over time to include the subject of aging, the decay of the body, and my thinking about biological enhancements to the body.

My earlier work on the subject of embodiment began with history and the technologies of war. In 1998, I retraced the steps of a death march of all women prisoners that took place at the close of World War II. The project is called Helmbrechts walk, 1998-2003 and it was meant as a non-monumental memorial to those women murdered during the march — 95 of them — and to those who survived it. To me, the artwork was my physical presence in the landscape, walking for 225 miles and occupying the space where their bodies had been but were no longer, and where a large number of women perished. Part of the narrative of Helmbrechts walk was not only the absence of these women in the landscape of the present, but the absence of female voices in the telling of the Holocaust itself. Until the demise of the Soviet Union, which opened up archives in the East to scholars, the story of the Holocaust as understood in the West, was told primarily in the voice of Western European men. Some of these men were truly extraordinary. One thinks of Primo Levi, Jean Amery, Tadeusz Borowski, Imre Kertész and Eli Weisel as examples. There are exceptions like Charlotte Delbo, Ida Fink and Anne Frank, but most of the experiential narratives were written by men and they are still the most familiar to general audiences.

I was acutely aware of the absence of these women in my present, some fifty-three years later, as I walked along and of the historical narrative of events that had brought them there, but also of the simple fact that they existed, housed in female bodies, and that 95 of them, starved and beaten, perished while being marched through that same landscape.

In an article by Saul Bellow in the New York Review of Books he quoted a passage from Lionel Abel's memoir The Intellectual Follies:

But I had no real revelation of what had occurred until sometime in 1946, more than a year after the German surrender, when I took my mother to a motion picture and we saw in a newsreel some details of the entrance of the American army into the concentration camp at Buchenwald. We witnessed the discovery of the mounds of dead bodies, the emaciated, wasted, but still living prisoners who were now being liberated, and of the various means of extermination in the camp, the various gallows, and also the buildings where gas was employed to kill the Nazis' victims en masse. It was an unforgettable sight on the screen, but as remarkable was what my mother said to me when we left the theatre: She said, "I don't think the Jews can ever get over the disgrace of this."1

It is this idea of being demoted to something less than human through the image of the "disgraced" body that stands out to me. In a recent interview with Ezra Klein — on the ethics of abortion, and thus a subject inextricably tied to female embodiment — the law professor Kate Greasley raised the question about the meaning that inheres in the developed human form itself and what we owe to it morally.2 At the end of my journey from Helmbrechts to Prachatice, I encountered a tiny museum made up of two small rooms; a commemoration of these women. It was created by the mayor of the town of Volary and his wife, the town next to Prachatice, where a number of the surviving women ended up. Images of a makeshift hospital in Volary depict two emaciated women on bare striped mattresses, both of whose bodies had been pushed beyond endurance. The photographs themselves, in which they are treated as specimens, read as a grotesque invasion of privacy and yet another indignity they are forced to endure. Their deaths can be foreseen in hollowness of their gazes. Neither survived, even though the march had ended.

Several years after I completed Helmbrechts walk, I encountered a newly dead sparrow on the sidewalk. It was still plump and warm and I was unable to leave it there. The act of bringing it home with me was the genesis of a decade long project, titled found birds, photographing and videotaping dead and decaying birds. I was not aware when I began photographing these dead birds that my images were related to the work I had done on the Holocaust. Somehow these small embodied creatures had unwittingly become a substitute for those images I had seen as a child, images that I cannot remember ever not having known about, of bodies stacked up like cordwood or being bulldozed into giant pits at liberated concentration camps. The bodies in those photographs were the ultimate disembodiment, because they no longer seemed to represent individual beings and because they depicted bodies that had gradually eaten themselves alive, disappearing from within until they could no longer sustain bodily functions. What remained of each was akin to a flattened leather husk.

Photo caption: being dead, 2010.

Recently, the outer body, or skin, has begun to be referred to as a "sleeve". Rather as if we can shed it like a snake, choosing to leave it behind. What was essential about those Holocaust victims was their complete lack of choice. They had no agency at all.

While it was obvious to me that my subject matter was the fragility of sentience, the underlying relationship between my series of found birds and Helmbrechts walk was not conscious at the outset. Yet, from their earliest deployment as stand-ins for Holocaust victims to their role as equal actor with me in the landscape, birds have been inextricably tied to the evolution of my work. The relationship between those first images of dead birds and the Holocaust was elucidated by G. Roger Denson in an article for the Huffington Post titled Holocaust and Redemption in the Photography of Susan Silas:

In this case, the birds acted metaphorically. But they are never far from their role in mythology or far from our desire to anthropomorphise them and to dispense with their wildness. As Roger Denson observes: "Unless we consider the easy death of birds as a key to acquiring the redemption that humans crave, anyone having experience with birds, or at least anyone who has witnessed birds in the throes of death, also knows how easily and quickly birds die upon encountering adversity or capture. Put a small bird from the wild like those Silas photographs in a cage, regardless of how well it's supplied with food and water, and it will be dead within days, even hours. And who hasn't seen a bird caught by a cat going limp within seconds of its capture even without mortal injury inflicted and with almost no struggle. It's hard not to think of this propensity of birds for the easy death/escape upon seeing their exquisitely photographed carcasses alongside the record of Silas's Helmbrechts walk. How much more merciful the easy death of birds appears next to our own endurance of imprisonment and terror. Anthropomorphised, it's such grace that has lent itself to the pronunciation of mystics that birds are the favourite creatures of gods.3

Photo caption: untitled (for David Foster Wallace), 2010.

Retrospectively, I can see that these dead and decaying birds were not merely stand-ins for the bodies of those victims, they were also an attempt to give some kind of dignity to those desecrated bodies; a perverse transubstantiation, through which degradation is morphed into beauty, attempting to intervene after the fact, in the systematic process of what Primo Levi described as the creation of "miserable and sordid puppets," because the shame of this demotion to something less than human haunted those bodies even in death.4

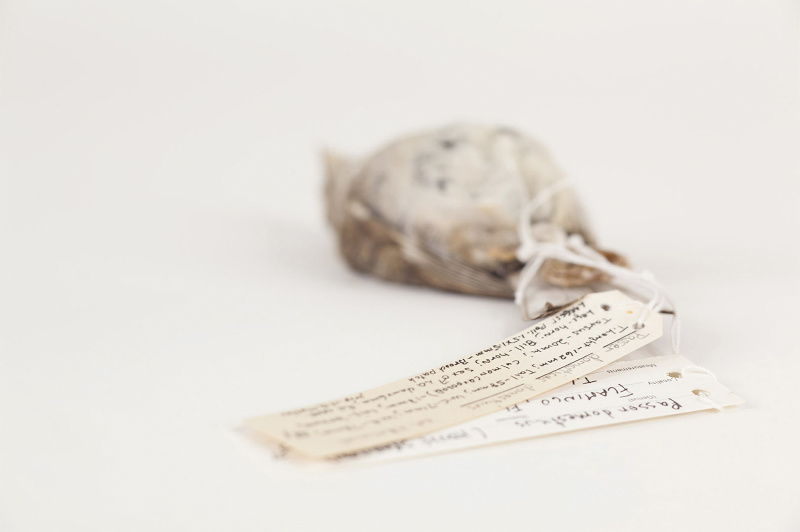

During a residency in the Everglades National Park, I took a somewhat different approach to death by looking at the way a taxidermised bird might be read with respect to the abandoned body. While at this residency, I was invited by The South Florida Collections Management Center to photograph the birds in its collection. The Center is tucked inside the park and within its temperature controlled darkened drawers, birds that inhabited the park as far back as the 1960s are laid out, each with a handwritten tag carefully tied to its feet, in much the same way that corpses are labelled at a morgue.

Photo caption: THE SPECIMEN DRAWER, 2013.

Some of these birds were roadkill, and a few sad specimens have labels indicating that they starved to death. They are, collectively, a part of the record of upheavals and changes in management techniques that have beset the park for over a century. Here the bird is not seen to gradually decay, but is preserved to resemble its embodied state in life. The drawers of birds reminded me of the preservation of national leaders, mostly communist ones came to mind, who are meant to be revered in death quite literally through the exhibition of their taxidermised bodies, an elevation as extreme on one the hand as the "disgraced" Holocaust victim is extreme on the other. Opening one of the Center's drawers, I momentarily imagine Lenin resting in his glass mausoleum in Red Square in the middle of Moscow or Ho Chi Minh's tomb, in Ba Dinh Square — a place from which he was conspicuously absent when I set off to see him as a tourist during a visit to Hanoi — he goes for a makeover to Moscow once a year, where the technology exists to spruce him up for future visitors. Some of the birds at The South Florida Collections Management Center, their bodies stiff and their eyes stuffed with cotton, have resided there as long as Ho has sat in his tomb at Ba Dinh Square. The same can be said of the corpse of Mao Tse Tung whose body had been lived in for 83 years and had been vacated for 38 years at the time of my visit to his mausoleum in Tienanmen Square.

Photo caption: THE SPECIMEN DRAWER, 2013.

The connection between the mausoleum and the desire for immortality it represents, and the preservation of these tiny bird bodies is ironic, in as much as the desire to control and assert total political will seems to exist in inverse proportion to the obligation to preserve our living habitat and other human beings. It is interesting that these preserved bodies all belonged to men, "communist" giants, one of whom was the greatest mass murder of the twentieth century, having killed an estimated 23 million people in the course of his lifetime. The reifying of their empty bodies was the only option open to them at the time of their deaths. One imagines now that they would have chosen to be cryogenically frozen in the hopes of being reanimated at a future date.

My recent thinking about embodiment has expanded beyond the subject of disembodiment through death and decay to examining the obsession among male researchers, of a new form of disembodiment in which humans abandon the mortal body and upload their minds in some form of data to a non-organic substrate and by so doing — achieve immortality. This project of bodily abandonment is aptly called Whole Brain Emulation.5 But while this project understands the vulnerability of the physical body, it is less convinced about its integration with the mind, and the mind's dependence on the body. This misunderstanding is bound to the desire to escape the obvious consequences of the mortal body. Denial of the importance of the body contributes to the continued degradation of our environment. My interest in the relationship between embodiment and new technologies has made me aware of the various ways in which the disavowal of the body is a direct threat to the sustainability of both the body and the planet. This should be completely obvious yet a great deal of rhetoric is expended to convince us that new technologies rather than a reconsideration of priorities is the only thing that can rescue us.

The decision to work with a live bird did not evolve directly from the work with dead birds, but rather because I had also been thinking about embodiment through the lens of classicism. I had begun to think about what the representation of an idealised older woman's body should or could look like and what it would mean to present an older body as an idealised form. The outcome of that thinking was a 24" tall marble sculpture, based on a scan of my body, called AGING VENUS, which was loosely modeled after Greek and Roman sculptures of Venus.

Photo credit: AGING VENUS, 2018.

Investigating classical sculpture came replete with a cast of characters from Greek and Roman mythology including Aphrodite, Daphne, Echo, Narcissus, and Leda, Queen of Sparta. The story of Leda and the Swan is of special interest because the rape/seduction of Leda by Zeus, in the form of a swan, resulted in the birth of Helen of Troy, reputedly the most beautiful woman in the world, who was presumed to have hatched from an egg, and whose beauty the Trojan War was supposedly fought for. But even more striking is that she could be seen as the cause of the demise of the belief in the world of the Greek gods. According to Ken Dowden, Professor Emeritus of Classics at the University of Birmingham, with the fall of Troy in 1200 BC "mythology ends."6

The fascination with the story of Leda and the Swan has not diminished since its first representation in 400 BCE. What is compelling to me is not the fact that the story has endured and that it has been passed on from generation to generation but that visual artists have consistently had a compulsion to represent it. The seduction/rape of Leda by Zeus has played out in mosaics discovered in Pompeii, in Greek and Roman statuary, in European painting and in twentieth century photography. Does she endure because the story is an illicit depiction of bestiality? In this story, Zeus resorts to seducing/raping Leda by adopting the form of a swan. Why would it be easier to seduce or rape her as a swan rather than as a god? And it is an eccentric form of bestiality, one in which it is not a mammal but a bird that copulates with a human. Is it that she is the spark that brings Greek mythology to a close, Zeus's act of lust somehow triggering his own demise? Or is it because we never really know if she was raped or seduced, potentially making Leda a very early emblem of #Metoo.

My video work, Leda and the Swan, 2019 is a work of performance for the camera. I was filmed with a wild bird, a male Mute swan in an enclosed warehouse. The premise was straightforward. The male swan and I were put into a room together to see what would happen. Leda and the Swan is not only a continuation of my exploration of questions of embodiment: "To thinking, cogitation, I oppose fullness, embodiedness, the sensation of being — not a consciousness of yourself as a kind of ghostly reasoning machine thinking thoughts, but on the contrary the sensation — a heavily affective sensation — of being a body with limbs that have extension in space, of being alive to the world," as J.M. Coetzee put it in The Lives of Animals.7 The video is also part of a contemporary lineage, starting with Joseph Beuys's famous 1974 performance, I Like America and America Likes Me, in which he places himself in a gallery with a coyote for eight hours, three days in a row. The lineage for my video also includes Mircea Cantor's 2005 work Deeparture, in which he placed a deer in a gallery space with a wolf. In all three videos there is the presumption of a predator/ prey relationship, each played out with different outcomes, but none where violence ensues. But the tension in these works is palpable nonetheless. And part of that tension revolves around our assumptions about the ethics of what we are watching and if our participation as viewers has somehow insinuated us into a situation that may or may not have moral implications with respect to the treatment of animals.

Photo caption: Leda and the Swan, 2019 (installation proposal).

Leda and the Swan functions as a counterpoint to the original myth and to the works of Beuys and Cantor, in that the video creates an ambiguous frame in which it is less clear which actor is meant as the predator and which as the prey. Working with a wild animal, it is impossible to predict exactly how it will behave in front of the camera. The outcome with the swan undercut the original myth about Leda and Zeus in several ways. The swan, enclosed in an interior space with me, an aging woman, took no interest in me whatsoever. Swans can be very aggressive but far from wanting either to attack or seduce me, he spent his time preening himself, completely narcissistically self-involved. He could sit contained for long periods, but when he was out-stretched he was as tall as I am. Occasionally squawking, the only other sound was of his footsteps. Whether sitting close to him or following him about the room, there was little sense of anything that might be seen as contact or connection. Rather, the communication between the two bodies was created through the responses to the video reported to me by the audience. Because there is little in the way of action in any of the five channels that make up the work, audiences began to contemplate the two bodies on the screen and compare my body with that of the swan in formal terms. In this sense the language of communication was literally body language.

Photo caption: Leda and the Swan, 2019 (production still).

What was striking to me about this response, in which the audience began to make formal comparisons between my body and that of the swan, is that it opened up a realm of thought that I had not entirely anticipated. My focus had been on a feminist upending of the Greek myth. In the recent interview with Ezra Klein mentioned earlier, Kate Greasley poses a question about how much dignity is due to another human being simply because we share the same casing or human form? If we begin to see a commonality between my casing and that of the swan, does that infer greater rights or consideration or empathy for the swan? Or given that my casing is female, does that rather relegate the swan to second class status? One might say that Greasley poses the fact of human embodiment alone as a sufficient ground for a moral imperative. This is at a time when the coinage of a new word is required to describe our geological era — the Anthropocene — indicating the degree to which we have altered the environment through human activity.8 Whether we see a formal comparison of the human form to the animal form as conferring some sort of special status or not, this is an opportune time to think about how anthropomorphism (a type of projection rather than just a formal comparison of the manifest form) functions. Anthropomorphism seems to engender two opposing impulses: the will to control and the desire to understand.

In John Berger's beautiful essay, Why Look at Animals? written in 1977, he says that consumer societies broke down the traditions that existed between man and nature, traditions that recognised that "animals were with man at the center of his world."9 Berger traces a shift in man's relationship to animals, one in which the exchange of the gaze between them disappears. "In the accompanying ideology, animals are always the observed. The fact that they can observe us has lost all significance. They are objects of our ever-extending knowledge. What we know about them is an index of our power and thus an index of what separates us from them. The more we know, the further away they are."10 Berger describes the public zoos that sprang up in Europe, "the Jardin des Plantes opened in 1793, the London Zoo in 1828 and the Berlin Zoo in 1844."11 These zoos, he tells us, were "an endorsement of modern colonial power."12 They caged and framed the distant conquests of all three imperial nations and allowed the public to share in the pride of conquest.

Photo caption: Leda and the Swan, 2019 (production still).

The Anthropocene brings us face to face with the consequences of that "pride of conquest." Anthropomorphism is often heralded as a way to create greater empathy for all of the lifeforms we share the planet with and thus as a tool that can be utilised to save the planet and perhaps some portion of the animal kingdom. But anthropomorphism has obviously not been enough. In the extraordinary 2009 film District 9 directed by Neill Blomkamp and set in Johannesburg, South Africa, an invasion of aliens called Prawns arrive on earth and begin living among the humans in a Johannesburg slum. These aliens are incredibly unappealing. The question the film raises is whether or not these others, even though we do not like or understand them, deserve just treatment. The question posed is a moral one and not reliant on whether we feel emotional empathy toward these creatures. In other words, even in the absence of a comfortable comparison between a human body and that of another life form or some avenue to project a feeling of commonality with them, do we owe just treatment to a sentient being, no matter how distinct from the human form?

In Leda and the Swan, the Mute swan finds itself in an interior space, architecture designed to house people and an environment hostile to the flourishing of a wild bird. In I to Eye, (the single channel version of a three-channel video the woman and the falcon), I am filmed with a female Peale's Peregrine falcon in the landscape of Cody, Wyoming. In I to Eye, the exposure of the naked human form to the sparse landscape of Cody, Wyoming is hostile to human flourishing but it is the natural habitat of the falcon, conducive to its thriving. In this way the videos have an inverse relationship to one another. In I to Eye, the relationship between my aging female body and the Peregrine falcon is also central and the falcon too, has its place in mythology. The god Horus was embodied as a falcon. In some cases, he was seen as a human body with a falcon's head. Once again, we see the fascination with the male body of a god transformed into a bird. Unlike the swan, however, who was cast as a seducer, the falcon generally represents power and nobility.

Photo caption: the woman and the falcon, 2022.

There is a long tradition of hunting using a trained falcon as a collaborator. Falconry is a particularly strong tradition in the Emirates and in the Middle East, which tend to be male dominated cultures, and where I would face difficulty showing much of my work due to the inclusion of female nudity. Falconry acknowledges the wildness of the bird as a first principal. While falcons who hunt with men (and a smaller number of women) are trained, that does not make them tame or domesticated. This is an important distinction. The symbolism of the naked female falconer, surely anathema to most falconers, and the acceptance of the wildness of the bird, were my points of departure. Here communication between the bird and the falconer is imperative. Through repetition and trust the falcon learns to hunt with its handler and knows that a reward can be expected in return, yet this does not eliminate choice on the part of the bird. Every time the falcon is set loose to fly, it can decide not to return to its handler and go free.

With I to Eye, we can return to John Berger and his observation that the "look between man and animal, which may have played a crucial role in the development of human society, and with which, in any case, all men had always lived until less than a century ago, had been extinguished."13 By creating an exchange of the gaze between the woman and the falcon, there is an attempt at recuperation. If the exchange of the gaze is re-established, what might that imply for the dignity of the falcon as well as that of the woman? While the director of the video is a woman, as is the actor, (and incidentally the crew), what remains to be interrogated is whether the fact of the naked female body on screen, as a matter of course, objectifies the female body and renders it subject to the scopophilic gaze, so astutely analysed in Laura Mulvey's 1975 essay, Visual Pleasure in Narrative Cinema. Mulvey describes scopophilia as a "circumstance in which looking itself is a source of pleasure, just as, in the reverse formation, there is pleasure in being looked at. Originally, in his Three Essays on Sexuality, Freud isolated scopophilia as one of the component instincts of sexuality which exist as drives quite independent of the erotogenic zones. At this point he associated scopophilia with taking other people as objects, subjecting them to a controlling and curious gaze."14

Photo caption: the woman and the falcon, 2022 (video still).

Is it possible to eke out a new territory that skirts that paradigm? Does the fact that it is an aging female body in any way mitigate the drive toward objectification or does the mere fact of female embodiment relegate the image to the category of "always the observed" on par with the animal kingdom in the male imperial cosmology? So many arguments regarding civil rights and the rights of animals are dependent on the initial framing of the questions. What happens if we create a frame that does not incorporate the scopophilic drive as an underlying assumption? Can that be declared by fiat? Or is it in fact a decision that each of us can make moment to moment, to see the same act as liberatory rather than trapped inside an old paradigm? Can we create a new model for looking? And can we reconceive of a way in which animals return to a place with "man at the centre of his world"? Or will we continue to devastate the habitats of animals and birds and threaten their chances for survival and our own?

As my work has evolved to include working with live birds, the emphasis has shifted to thinking about how we inhabit the world together. Birds have become progressively more imperiled. "Nineteen species were lost in the last quarter of the twentieth century, and three species are known or suspected to have gone extinct since 2000."15 When the Americas were first settled, passenger pigeons were so numerous that the entire sky would darken as if night had fallen, when a flock of them flew by. "Alexander Wilson, wrote that 'while visiting friends in New England, sitting in the kitchen suddenly the sky became dark, there was no light in the room, and a rumbling noise grew louder, I was certain it was a tornado.' When his friends saw how frightened he was, they exclaimed, 'Oh, it's only the pigeons flying overhead'."[16] Now not a single passenger pigeon remains.

Photo caption: the woman and the falcon, 2022 (video still).

In Jorge Semprun's memoir Literature or Life he observed that after the "liberation" of Buchenwald the birds had returned to the Ettersberg.[17] Like Virgil entering the underworld, Semprun observed that in the hell of Buchenwald, located in a dense forest of Weimar, all the birds had fled, driven away by: "The smell from the crematory. The smell of burning flesh." The Greeks called the underworld Avernus, the Birdless Place. If as Roger Denson tells us, it is the grace of birds that led mystics to believe they are the favorite creatures of the gods, what will remain of our world if we are responsible for their mass extermination?[18]

Works Cited

Bellow, Saul. A Jewish Writer in America, The New York Review, 10 November 10, 2011. Berger, John. "Why Look at Animals," About Looking, Vintage International, 1980.

Coetzee, J.M. The Lives of Animals, Princeton University Press, 1999.

Crutzen, Paul J and Christian Schwägerl. Living in the Anthropocene: Toward a New Global Ethos, Yale Environment 360, 24 January 2011, Website.

Data Zone. BirdLife International, Website.

Denson, G. Roger. Holocaust and Redemption in the Photography of Susan Silas, The Huffington Post, 5 April 2011, Website.

Dowden, Ken. Greek Mythology 3500BC-AD2014, University of Birmingham, 3 February 2014, Website.

Greasley, Kate and Klein Ezra. Transcript: Ezra Klein Interviews Kate Greasley, The New York Times, 20 May 2022, Website.

Levi, Primo. Survival in Auschwitz, Simon and Schuster, 1996.

Mulvey, Laura. Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Amherst.edu, PDF.

Noteworthy Stories and Quotes about The Passenger Pigeon, Website.

Semprun, Jorge. Literature of Life, Penguin Books: USA, 1997.

Footnotes

- Saul Bellow, "A Jewish Writer in America," The New York Review, 10 November, 2011. ↩

- Kate Greasley and Klein Ezra, "Transcript: Ezra Klein Interviews Kate Greasley," The New York Times, 20 May 2022, (Website). ↩

- Roger G. Denson, "Holocaust and Redemption in the Photography of Susan Silas." The Huffington Post, 5 April 2011, (Website). ↩

- Primo Levi, Survival in Auschwitz, Simon and Schuster, 1996, 26. ↩

- 'Whole Brain Emulation,' Wikipedia, (Website). ↩

- Ken Dowden, Greek Mythology 3500BC-AD2014, University of Birmingham, 3 February, 2014, (Website). ↩

- The fascination with the story of Leda and the Swan has not diminished since its first representation in 400 BCE. What is compelling to me is not the fact that the story has endured and that it has been passed on from generation to generation but that visual artists have consistently had a compulsion to represent it. The seduction/rape of Leda by Zeus has played out in mosaics discovered in Pompeii, in Greek and Roman statuary, in European painting and in twentieth century photography. Does she endure because the story is an illicit depiction of bestiality? In this story, Zeus resorts to seducing/raping Leda by adopting the form of a swan. Why would it be easier to seduce or rape her as a swan rather than as a god? And it is an eccentric form of bestiality, one in which it is not a mammal but a bird that copulates with a human. Is it that she is the spark that brings Greek mythology to a close, Zeus's act of lust somehow triggering his own demise? Or is it because we never really know if she was raped or seduced, potentially making Leda a very early emblem of #Metoo. J.M. Coetzee, The Lives of Animals, Princeton University Press, 1999, 33. ↩

- Paul J Crutzen and Christian Schwägerl, Living in the Anthropocene: Toward a New Global Ethos, Yale Environment 360, 24 January 2011, (Website). ↩

- with man at the center of his world."[16] Berger traces a shift in man's relationship to animals, one in which the exchange of the gaze between them disappears."In the accompanying ideology, animals are always the observed. The fact that they can observe us has lost all significance. They are objects of our ever-extending knowledge. What we know about them is an index of our power and thus an index of what separates us from Berger, About Looking, 16. ↩

- Berger, About Looking, 21. ↩

- Berger, About Looking, 21. ↩

- With I to Eye, we can return to John Berger and his observation that the "look between man and animal, which may have played a crucial role in the development of human society, and with which, in any case, all men had always lived until less than a century ago, had been extinguished."[17] By creating an exchange of the gaze between the woman and the falcon, there is an attempt at recuperation. If the exchange of the gaze is re-established, what might that imply for the dignity of the falcon as well as that of the woman? While the director of the video is a woman, as is the actor, (and incidentally the crew), what remains to be interrogated is whether the fact of the naked female body on screen, as a matter of course, objectifies the female body and renders it subject to the scopophilic gaze, so astutely analysed in Laura Mulvey's 1975 essay, Visual Pleasure in Narrative Cinema. Mulvey describes scopophilia as a "circumstance in which looking itself is a source of pleasure, just as, in the reverse formation, there is pleasure in being looked at. Originally, in his Three Essays on Sexuality, Freud isolated scopophilia as one of the component instincts of sexuality which exist as drives quite independent of the erotogenic zones. At this point he associated scopophilia with taking other people as Laura Mulvey, Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema, Amherst.edu, (PDF), 806. ↩

- As my work has evolved to include working with live birds, the emphasis has shifted to thinking about how we inhabit the world together. Birds have become progressively more imperiled. "Nineteen species were lost in the last quarter of the twentieth century, and three species are known or suspected to have gone extinct since 2000."[18] When the Americas were first settled, passenger pigeons were so numerous that the entire sky would darken as if night had fallen, when a flock of them flew by. "Alexander Wilson, wrote that 'while visiting friends in New England, sitting in the kitchen suddenly the sky became dark, there was no light in the room, and a rumbling noise grew louder, I was certain it was a tornado.' When his friends saw how frightened he Noteworthy Stories and Quotes about The Passenger Pigeon, (Website) ↩

- Jorge Semprun, Literature or Life, Penguin Books USA, 1997, 94. ↩

- Denson, Huffington Post. ↩