Unseeing Elegy of the Tetrachromats

by Jessica Laraine Williams, Roger Alsop, and Mathew L Berg

- View Jessica Laraine Williams' Biography

Jessica Laraine Williams is a transdisciplinary researcher, artist and digital allied health specialist.

- View Roger Alsop's Biography

Roger Alsop is a multi-modal artist who focuses on the translation of communication processes and methods in the creation of artworks.

- View Mathew L Berg's Biography

Mathew L Berg is a conservation biologist and evolutionary ecologist based in Geelong, Australia

Unseeing Elegy of the Tetrachromats

Jessica Laraine Williams, Roger Alsop and Mathew L. Berg

Photo credit: Jessica Laraine Williams, Mathew Berg, Alex Last, Roger Alsop. Unseeing elegy of the tetrachromats , 2021, digital photograph.

Incubating the artwork

Unseeing elegy of the tetrachromats (2021) is an artwork that imagines the sensory lifeworld of an endemic Australian bird, the crimson rosella (Platycercus elegans). Exhibited online, it accompanied the 'Birds and Language' conference hosted by the University of Sydney in 2021. Construed across three discrete yet interlocutory parts, the artwork is encountered as recorded performance, video, and sound, each contributed by artists Jessica Laraine Williams, Roger Alsop and Alex Last (see figure 1 and the online exhibition via the link below). The artists collaborated with ecologist Mathew L. Berg in order to interrogate an anthropocentric trope in art: rather than focus on the human-centered spectator of art, Unseeing elegy speculates on birds as the primary audience, revealing the corollary tensions inherent in creating artwork for nonhuman 'tastes' and perceptions.

Figure 1. Jessica Laraine Williams, Mathew Berg, Alex Last, Roger Alsop. Unseeing elegy of the tetrachromats, 2021, screenshots of the online exhibition, video and sound, dimensions variable.

This paper presents documentation of the Unseeing Elegy artwork accompanied by a transdisciplinary scholarly commentary, provided by Williams, Alsop, and Berg across three respective sections. The overall account incorporates current understandings in avian ecology, concepts prominent in the broader field of posthuman studies and practices, and our experiences in making the work.

We commenced the project by attending to the physiological capacities of rosellas in vision and hearing, noting how these senses shape the birds' engagements with the environment and with one another. Berg grounds our commentary through an ecological perspective on the auditory and visual complexes of the crimson rosella, motivated by over a decade of sustained research on the species. His scientific insight served as a provocation for response by Alsop and Williams, who speculated on unknown and alternative axes of avian subjectivity through two different approaches in artistic expression. Both of their contributions were structured by the absence of readily accessible technologies for production and display to nonhuman audiences, especially those oriented to the sensorium of avian subjects. During development of the work, the project team were separated by Covid-19 lockdowns and interstate travel bans, necessitating asynchronous production and a digitally-delivered final outcome.

Documenting his process, Alsop discusses his artistic rationale for translating rosella song into human systems of communication. His contribution aimed to reconcile unseen and underrepresented notions of language with a dominant syntax of anthropocentrism. Next, Williams considers the rosella's ability to see ultraviolet light (enabled by their four-dimensional vision, or tetrachromia). Her performance intervention into this visual complex, which was eventually presented to rosella spectators as the primary audience, aligns concepts of multispecies invitation and the posthuman gaze in Williams's contribution to the overall artwork. The paper concludes with a short summary of findings elucidated from the Unseeing elegy project, including scope for additional opportunities in research and creative work. With this extended reflection, we engage audiences in current transdisciplinary practices addressing posthuman subjectivity, accounting for an expanded register of sensory affect as experienced by birds.

An ecological perspective on rosella senses

Mathew L Berg

The field of sensory ecology is concerned with how animals use their sensory abilities to interact with each other and their environment. Contemporary sensory ecology is a vibrant field that integrates empirical study of behaviour, physiology and genetics. In this section, I offer a brief overview of what some of this research entails, and hence the scientific provocation for the Unseeing elegy artwork.

Through my research as a sensory ecologist, I have had a special interest in exploring how birds, particularly parrots, communicate through a variety of sensory modalities and what these abilities mean for how they live their lives. Most notably, I have been part of a team that has sought to understand how crimson rosellas produce and perceive visual, acoustic and olfactory signals. A major drawcard of rosellas for this research is the variability in their plumage coloration; ironically, not all crimson rosellas are in fact crimson, or indeed any shade of red. Some populations are dull yellow, others an intermediate orange or a mix of all of those (Ribot, Berg, Schubert, et al.). This represents a striking range in morphology for just one species and offers a tantalising opportunity to study how such variation comes about, and what it means for the birds.

One of the most influential recent advances in understanding avian sensory ecology has been the realisation that not only do many birds perceive colours based on ultraviolet (UV) wavelengths of light (around 320-400 nanometres), which are invisible to our eyes, but also that plumage often reflects UV light intensely. These abilities can be crucial to how they express essential behaviours such as choosing mates and camouflaging themselves (Kemp et al.). A trait that fundamentally sets birds apart from humans and other mammals, and which contributes to this capacity for UV colour vision, is that they are tetrachromatic (Kelber). That is, they have four types of colour-sensing cells, or 'cone cells', in the retina. In contrast, humans have three classes of cone cells — typically sensitive to red, green and blue — and among mammals only certain rodents and marsupials seem to have UV sensitive vision.

Despite all bird species being tetrachromatic, not all are strongly UV sensitive; rather, many are what visual physiologists refer to as 'violet sensitive'. Accordingly, all birds see in more colour dimensions than a trichromatic species such as humans, but not necessarily always into the ultraviolet range. In fact, the colour vision of bird species appears to fall into two discrete groups based on whether they are ultraviolet sensitive or violet sensitive.

My recent research has investigated using genetic sequencing and physical measurements of light transmission in the retina cells of crimson rosellas and a number of other parrot species. This work revealed the sensitivity of parrot eyes to different wavelengths of light, and in particular the UV wavelengths (Carvalho et al.; Knott et al.). Based on the results of these studies, we now postulate that parrots and cockatoos might be the only major grouping, or in taxonomic terms Order, of birds in which UV sensitive vision is ubiquitous across all species. This is not without ecological significance, as objects in nature, such as fruit and flowers, also strongly reflect UV light. It follows that many of these are perceived as UV-rich colours to species with UV sensitive vision. In fact, much bird plumage reflects strongly in UV wavelengths, creating patterns and visual variation invisible to our eyes (such plumage patches usually appear blue to us) but visible to UV sensitive bird species.

One creative approach that researchers have used to study how this might be perceived by birds is by applying sunscreen to the plumage. Sunscreen chemicals have the useful property of blocking the UV reflectance from the feathers being transparent to other wavelengths. When applied to plumage, researchers have artificially created areas of 'UV-deleted' plumage on the birds, to see if this affects interactions with others of their species (Andersson and Amundsen; Sheldon et al.).1 In the Unseeing elegy project, Williams adapts this into a non-invasive approach, applying sunscreen to objects rather than the birds themselves (see below).

Another condition that sets bird vision apart is that they usually have relatively high 'flicker fusion thresholds'. This implies that objects that flicker so rapidly that they appear as a constant steady light to us, such as computer screens and fluorescent lights, might appear as flickering objects to many birds. This could assist them in avoiding objects when flying quickly through cluttered environments like forests and woodlands. In parrots, the threshold for flickering is probably around 50% higher than our own eyes, especially in low light (Boström et al.).

The visual world inhabited by parrots is rich and intangible to us — what, then, about acoustic communication? In many respects the hearing abilities of parrots, and many other birds, seem to be broadly similar to our own, at least in terms of the frequencies and amplitudes to which they are most sensitive (Graham et al.; Wright, Cortopassi, et al.). However, within these parameters birds produce, as humans do, extraordinarily diverse and intricate sequences of sounds. These are in some cases innate and genetically determined, and in others acquired and modified throughout life. Indeed, outside of humans, parrots are the 'poster group' for a powerful vocal trait that is in fact quite widespread in birds yet rare in animals generally: vocal learning. We are most familiar with the vocal learning abilities of parrots through their capacity to mimic human speech, but in their natural lives this ability plays an important role in social cohesion. Cultural transmission of call dialects can even take place at the scale of specific roosting trees in some wild parrot flocks (Bradbury and Balsby; Wright, Rodriguez, et al.). In rosellas, many of the calls they produce are context specific, some are specific to different populations and others still tend to be specific to the individual bird (Ribot, Berg, Buchanan, et al.).

These and similar studies2 continue to advance our understanding of sensory ecology, providing ever growing ecological insight into the rich and multifaceted 'language' of birds. In drawing on these knowledges, the artists' responses presented here embody a fascinating pathway to meaningful interaction between arts and contemporary empiricism which has the potential to return a valuable benefit to outcomes sought by the scientific endeavour. This includes increasing awareness of the diverse sensory worlds inhabited by species other than our own, and cultivating an appreciation among the community of a moral imperative to ensure their persistence.

Rosella Alphabet

Roger Alsop

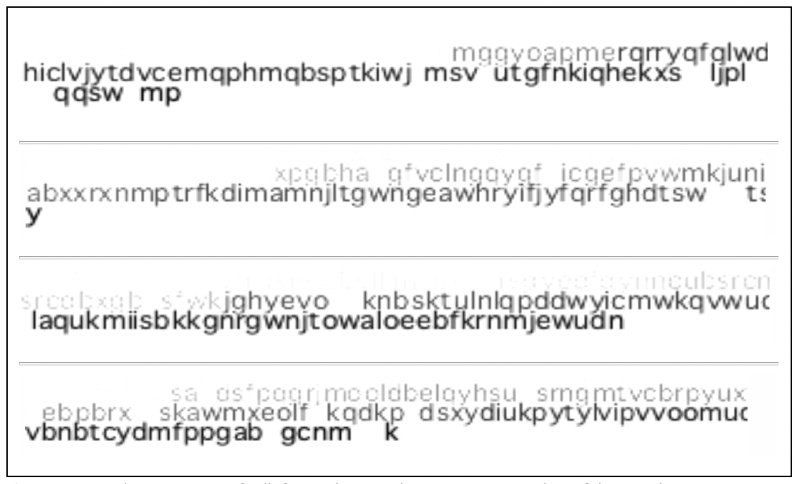

Figure 2. Roger Alsop. Rosella alphabet, contribution to Unseeing elegy of the tetrachromats, 2021, video and sound, dimensions variable.

Figure 3. Roger Alsop. Sequence of stills from video contribution to Unseeing elegy of the tetrachromats, 2021, video and sound, dimensions variable.

Figure 3 represents a translation of rosella vocalisations (I will use the colloquial term song) into English letters. This may seem a ridiculous act, yet it does aim to address notions of the more-than-human. Here I am considering the more-than-human as beyond the scope suggested by a 'post-' or 'trans-' humanism as couched in technologies (Vita-More 'History of Transhumanism; Vita‐More 'Aesthetics'; Braidotti, 'A Theoretical Framework for the Critical Posthumanities'; Braidotti, The Posthuman). I question the centralising of the human and their quantifiable achievements within what exists as a potential path forward: a version of ourselves enhanced by technologies we have invented.

In developing this piece, I went through a number of approaches to translating the rosella song into a different expression, one more reconciled to human perceptions. Initially, I slowed the recording of the song by a factor of 0.001, which allowed me to hear relationships between the phrases. I then considered ways that the sound could be represented visually. My first approach was to have the frequencies of the birdsong expose pixels of an image of a rosella; each frequency was given a Cartesian coordinate, and when a frequency was heard, the pixels at that coordinate were shown. The resulting images were visually interesting, yet I felt they did not represent the bird calls as a language. I consider language in this work to be an abstracted set of sounds used to indicate a concept or object (Fromkin et al.). The written word is a set of further abstracted graphemes, which represent those sounds used to express an idea. Secondly, I experimented with the changing frequencies and onset times of the song, using Cartesian coordinates to generate geometric designs. Whilst interesting, this did not sufficiently represent my working definition of language as above.

I decided to simplify the artistic translation by having the frequencies relate directly to ASCII code. This choice was made because ASCII code is fundamental to modern communication. While the code itself may seem opaque — for example, my name is represented as 82 111 103 101 114 — its standardization makes it a near universal lingua franca. To translate the rosella song into ASCII numbers, I compressed the frequency values to fit between 65 and 122, the ASCII numbers representing the letters A to Z. This resulted in the lower frequencies of the rosella song producing upper case letters, and the higher frequencies producing lower case letters. Higher amplitudes then triggered the generation of the letters; this was done to filter out ancillary noise in the recording. I had arrived at my 'rosella alphabet' and the resultant video contribution to Unseeing elegy (see figure 2).

In the video, we see that new letters — triggered by new sounds — appear in dark font on the screen. The letters then fade gradually, taking our focus to the newly generated text. This choice was made to represent the fading of both the sound and our memory of it. This opposes the notion that the written word is permanent, something that can be re-viewed, with the belief that what is re-viewed is an accurate re-presentation of something that occurred in the past. The written word (what we see in the video) obviates the need for memory, and the written word is an instrument unique to the human species.

Where I propose that human and animal languages slightly converge is in the arbitrariness of sounds that signify meaning, which can be seen, for example, in different sounds being used to alert different types of danger, location or to attract those of the same species (Beecher). The written word is an arbitrarily applied visual signifier of sounds that have an arbitrarily applied meaning, and these signifiers are broader than danger or attraction. There are also arbitrary rules applied to the sequences of sounds in any given human language, its syntax, and it is reasonable to assume that similar rules exist for the languages of other species, in this case birds (van Heijningen et al.; Gentner et al.; Berwick et al.).

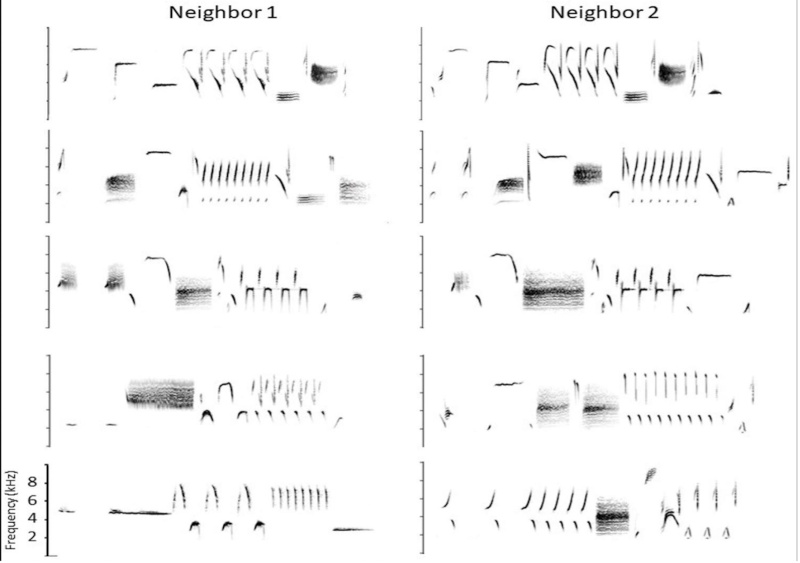

The text that appears in my contribution, while adhering to traditional English language signifiers of sounds, does not follow the traditional English language rules. Beecher's sonographic images of partial song repertoires of two neighbouring sparrows (figure 4) indicate a potential syntax (much more analysis would be required to make a definitive statement), and perhaps a syntax could be gleaned from the text shown in my rosella alphabet.

Figure 4. Michael Beecher. Sonographic images of partial song repertoires of two neighbouring sparrows. "Why Are No Animal Communication Systems Simple Languages?" Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 12, 2021, p. 8.

The main aim of creating a rosella alphabet was to interrogate the notion of viable sense: even though we may not fully understand or be invested in a given sense, its possibilities remain viable for speculation. This is part of an ongoing/evolving set of works that intend to question tropes of the human-centered originator/spectator, creating works that have a nonhuman root/cause expressed through human systems.

To the avian gaze, unseen

Jessica Laraine Williams

Figure 5. Jessica L. Williams's contribution to Unseeing elegy of the tetrachromats, 2021, video and sound, dimensions variable.

"As with every bottomless gaze, as with the eyes of the other, the gaze called animal offers to my sight the abyssal limit of the human..." (Derrida 381)

Prior to initiating the Unseeing elegy project with the collaborative team, my doctoral research had been delving into several critical frameworks, including the conception of the posthuman gaze. I had substantiated this first through considering algorithmic vision in the virtual subject, then expanded my inquiry into possibilities for the avian subject. This turn was significantly motivated through with the idea of the Umwelt, the Uexküllian notion that every animal possesses a distinct and differential sensory universe to that of humans, each containing experiences unique to that animal's lifeworld (von Uexküll et al.). Planning my contribution to Unseeing elegy, I focused on considering the specificities and proclivities of rosella vision, influenced by the argument on differential attentiveness put forth by Syl and Aph Ko in their book Aphro-Ism: Essays on Pop Culture, Feminism, and Black Veganism from Two Sisters. Syl Ko advocates for granular investigations on the unique material conditions of animals, acknowledging their biological status and embeddedness in distinct ecological systems, whilst also accepting the limitations of attempting to reconcile animal agencies with our own. Analysing the entwined oppressions that are enacted across nonhuman animals and race, Ko asserts that these are often tied to"...the larger, grander narrative that establishes who is human and innately valuable and who is not — a story that is not and never has been based on biology or biological facts." (Ko, 'Notes from the Border of the Human-Animal Divide: Thinking and Talking about Animal Oppression When You're Not Quite Human Yourself' 72).3 Through this critical prism, I thus determined my key inquiry for the work of Unseeing elegy: how might we recognise animals' legitimacy as complex, sensate entities to which we owe a debt of conservation and respect? Following Derrida's seminal discussion in The Animal That Therefore I am, one approach is to recognise the experience of the 'seeing animal' that looks at us reciprocally as we look upon them (Derrida 383).

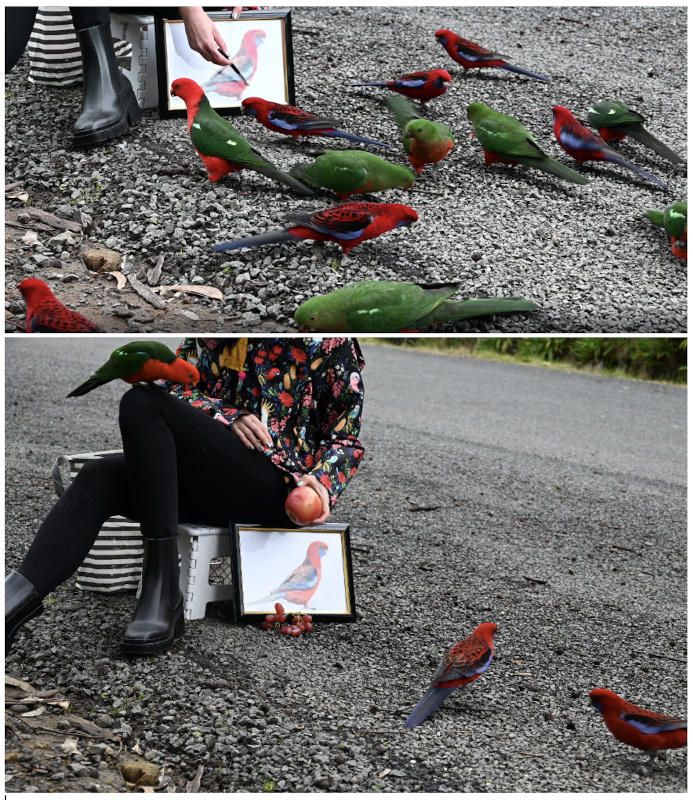

In my contribution to the artwork, I wanted to explore an intervention into the visual experience of avian tetrachromia, proposing a spectacle for birds that might approximate the lack of UV perception in human vision. In attempting to simulate human sensory perspectives for the nonhuman viewer, my work inverts a common anthropocentric trope in human-animal imaginaries.4 After consulting with Berg and the ecological literature, I decided to adapt my protocol from prior studies that have modified the UV reflectance of birds with the use of sunscreen (Andersson and Amundsen; Sheldon et al.). Opting for a non-invasive approach, I selected objects to paint with sunscreen in a planned performance that would invite rosella viewers in the field. Berg suggested ephemera that would be of specific appeal to the parrots, noted across his years of experience spent observing their preferences and interests in the field. Berg observed that common rosella behaviours included social interactions with each other and the procurement of food. Hence, I selected grasses, fruits (see figure 6) and a coloured pencil drawing of a crimson rosella (see figures 7 and 8); beyond response to their feeding behaviours, I wondered if a visual offering of likeness could also invite any interest from these birds.

Figure 6. Jessica L. Williams. Fruit and grasses used in the artist's performance.

Amidst local Covid-19 restrictions, I was initially limited to the home space, unable to encounter rosellas in the field. I set about enacting my performance to four cohabiting bantam chickens (Gallus gallus domesticus) in a pilot attempt to stage the work. Like all birds, chickens are tetrachromats (Kelber). Irrevocably reminded of the lure of free-flowing drinks and canapes at a gallery showing for humans, I offered the chickens a feed in simultaneity with my sunscreen-painting routine (see figure 7). Beyond their obvious propensity to an extra helping of seeds and their ease in my presence (likely garnered over six years of kinship at the time), I was unable to discern the artistic impact of this performance on my chicken audience. Were they especially engaged, disapproving or curious towards the spectacle that was occurring outside of their normal routine? I couldn't be sure, although they did seem generally amenable to my activity. Zoömusicologist Hollis Taylor has contemplated similar nuances in her co-productive practice of making music with pied butcherbirds. Taylor interpreted participatory non-consensus from her avian subjects through behaviours such as swooping or harsh vocalizations (Taylor 48). Extrapolating this index to my free-ranging chicken companions, a type of agreeable consent might then be represented by both their decision to maintain a physical closeness to the performance and the absence of obvious adverse reactions. I am hesitant to generalize this observation much further in the receptivity of the chickens to my artwork, especially as the dynamic between us was one of domestic human-animal relation. To me, domesticity entangles a centering of human desires with systematic, generational manipulation of nonhuman animals.5 We curate animal bodies and behaviours to reflect an ideal self in them: we tend to search for signs that relate their affections, mutual recognitions and even a propensity to artistic pursuits with our own.

Figure 7. Jessica L. Williams. Trial performance of sunscreen painted on objects to an audience of domestic chickens.

The following week, I was able to exit stay-at-home restrictions in a brief interim between quarantine orders. I knew that wild rosellas frequented a particular site in my region where local residents and visitors had established a tradition of feeding them sunflower seeds — an inadvisable practice that risks dependency by the birds, but one that had previously taken hold in this community. Driving along the Victorian Great Ocean Road towards the town of Lorne, I wondered if the birds at the site would be so accustomed to humans and an easy meal that they had both confidence and leisure-time available for the viewing of art. I was overarchingly anxious that they would not be at the site at all.

Figure 8. Jessica L. Williams. Documentation of the artist's recorded performance for Unseeing elegy of the tetrachromats. A mixed flock of Australian king parrots and crimson rosellas were present.

Fortunately, my recorded performance for Unseeing elegy was given not only to crimson rosellas, but to a mixed flock additionally comprised of overly familiar Australian king parrots (Alisterus scapularis) (see cover image and figure 8). This assemblage was frequently punctuated by the sauntering passage of large sulphur-crested cockatoos (Cacatua galerita) through the milieu. As captured in my video contribution to the artwork (see figure 5), the flock clustered around my locus of activity with a surprising persistence. Whilst once again it was difficult to ascertain the birds' artistic reception to my performance, their close proximity and enthused attentiveness indicated that I had, at the very least, offered these avian subjects an entertaining experience that afternoon.

Figure 9. Jessica L. Williams. A crimson rosella closely inspects the artist's photography gear, with two sulphur-crested cockatoos in the background.

Aloft

Unseeing elegy of the tetrachromats imagines the sensory lifeworld of birds outside of a human-centered homologue. Responding to ecological narratives described by Berg, Alsop explored alterior registers for language through his artistic translation of birdsong, and Williams invited birds to spectate a performance that was tailored to the avian gaze. Our transdisciplinary approach follows the ethos of Maria Puig de la Bellacasa, whose work at the crossing of feminist science, technology studies and ecological thinking privileges an ethics of care. She notes that "...reconnecting a politics of commitment and of ethical obligation with an ontology of more than human worlds [without falling back into classic humanist categories of thought] requires a speculative effort" (Puig de la Bellacasa 16). In this way, the Unseeing elegy project promotes a radical care for avian subjectivity; navigating the development of the artwork encouraged the authors to cross disciplinary boundaries as we continuously triangulated ourselves inside a zone of speculative generativity. We recognise that an expansion of the project's approach (exceeding the limitations of the pandemic context) could foster further collaborative exchange between our practices, such as placing the artistic contributions in direct dialogue with one another. Additionally, there is scope for our critical orientation to the avian subject to be enriched through connection with broader discourses, such as those held in traditional ecological knowledge systems. In the shared encounter of art, Unseeing elegy opened a space to communicate human-nonhuman concordances across the multispecies divide. This work corroborates both a posthumanist drive to affirm new modes of intersubjective relation, and the urgent conservationist call to highlight the uniqueness of other existences that may go unrecognised or unseen.

Works Cited

Andersson, Staffan, and Trond Amundsen. 'Ultraviolet Colour Vision and Ornamentation in Bluethroats'. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, vol. 264, no. 1388, Nov. 1997, pp. 1587-91. royalsocietypublishing.org (Atypon), https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.1997.0221.

Beecher, Michael D. 'Why Are No Animal Communication Systems Simple Languages?' Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 12, 2021. Frontiers, Website.

Berwick, Robert C., et al. 'Songs to Syntax: The Linguistics of Birdsong'. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, vol. 15, no. 3, Mar. 2011, pp. 113-21. ScienceDirect.

Boström, Jannika E., et al. 'The Flicker Fusion Frequency of Budgerigars (Melopsittacus Undulatus) Revisited'. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, vol. 203, no. 1, Jan. 2017, pp. 15-22. Springer Link.

Bradbury, Jack W., and Thorsten J. S. Balsby. 'The Functions of Vocal Learning in Parrots'. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, vol. 70, no. 3, Mar. 2016, pp. 293-312. Springer Link.

Braidotti, Rosi. 'A Theoretical Framework for the Critical Posthumanities'. Theory, Culture and Society, May 2018, p. 0263276418771486. ma.

—. The Posthuman. Hoboken, NJ: Polity Press, 2013.

Carvalho, Livia S., et al. 'Ultraviolet-Sensitive Vision in Long-Lived Birds'. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, vol. 278, no. 1702, Jan. 2011, pp. 107-14. royalsocietypublishing.org (Atypon).

Derrida, Jacques. 'The Animal That Therefore I Am (More to Follow)'. Critical Inquiry, translated by David Wills, vol. 28, no. 2, 2002, pp. 369-418.

Fromkin, Victoria, et al. An Introduction to Language. Cengage Learning, 2013.

Gentner, Timothy Q., et al. 'Recursive Syntactic Pattern Learning by Songbirds'. Nature, vol. 440, no. 7088, 7088, Apr. 2006, pp. 1204-07. www.nature.com.

Graham, Jennifer, et al. 'Sensory Capacities of Parrots'. Manual of Parrot Behavior, 2006, p. 33.

Hausmann, Franziska, et al. 'Ultraviolet Signals in Birds Are Special'. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences, vol. 270, no. 1510, Jan. 2003, pp. 61-67. royalsocietypublishing.org (Atypon).

Kelber, Almut. 'Bird Colour Vision - from Cones to Perception'. Current Opinion in Behavioral Sciences, vol. 30, Dec. 2019, pp. 34-40. ScienceDirect.

Kemp, Darrell J., et al. 'An Integrative Framework for the Appraisal of Coloration in Nature'. The American Naturalist, vol. 185, no. 6, June 2015, pp. 705-24. www-journals-uchicago-edu.eu1.proxy.openathens.net (Atypon).

Knott, Ben, et al. 'Absorbance of Retinal Oil Droplets of the Budgerigar: Sex, Spatial and Plumage Morph-Related Variation'. Journal of Comparative Physiology A, vol. 198, no. 1, Jan. 2012, pp. 43-51. Springer Link.

Ko, Syl. 'Addressing Racism Requires Addressing the Situation of Animals'. Aphro-Ism: Essays on Pop Culture, Feminism, and Black Veganism from Two Sisters, Lantern Books, 2017, pp. 44-49.

—. 'Notes from the Border of the Human-Animal Divide: Thinking and Talking about Animal Oppression When You're Not Quite Human Yourself'. Aphro-Ism: Essays on Pop Culture, Feminism, and Black Veganism from Two Sisters, Lantern Books, 2017, pp. 70-75.

Mihailova, Milla, et al. 'Odour-Based Discrimination of Subspecies, Species and Sexes in an Avian Species Complex, the Crimson Rosella'. Animal Behaviour, vol. 95, Sept. 2014, pp. 155-64. ScienceDirect.

—. 'Olfactory Eavesdropping: The Odor of Feathers Is Detectable to Mammalian Predators and Competitors'. Ethology, vol. 124, no. 1, 2018, pp. 14-24. Wiley Online Library.

Puig de la Bellacasa, María. Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

Ribot, Raoul F. H., Mathew L. Berg, Katherine L. Buchanan, et al. 'Is There Variation in the Response to Contact Call Playbacks across the Hybrid Zone of the Parrot Platycercus Elegans?' Journal of Avian Biology, vol. 44, no. 4, 2013, pp. 399-407. Wiley Online Library.

Ribot, Raoul F. H., Mathew L. Berg, Emanuel Schubert, et al. 'Plumage Coloration Follows Gloger's Rule in a Ring Species'. Journal of Biogeography, vol. 46, no. 3, 2019, pp. 584-96. Wiley Online Library.

Sheldon, Ben C., et al. 'Ultraviolet Colour Variation Influences Blue Tit Sex Ratios'. Nature, vol. 402, no. 6764, 6764, Dec. 1999, pp. 874-77. www.nature.com.

Taylor, Hollis. 'Marginalized Voices: Zoömusicology through a Participatory Lens'. Participatory Research in More-than-Human Worlds, edited by Michelle Bastian, Routledge, 2017.

van Heijningen, Caroline A. A., et al. 'Simple Rules Can Explain Discrimination of Putative Recursive Syntactic Structures by a Songbird Species'. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, vol. 106, no. 48, Dec. 2009, pp. 20538-43. pnas.org (Atypon).

Vita-More, Natasha. 'Aesthetics: Bringing the Arts and Design into the Discussion of Transhumanism'. The Transhumanist Reader: Classical and Contemporary Essays on the Science, Technology, and Philosophy of the Human Future, 2013, pp. 18-27.

—. 'History of Transhumanism'. The Transhumanism Handbook, Springer, 2019, pp. 49-61.

von Uexküll, Jakob, et al. Foray into the Worlds of Animals and Humans: With A Theory of Meaning. University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

Wright, Timothy F., Kathryn A. Cortopassi, et al. 'Hearing and Vocalizations in the Orange-Fronted Conure (Aratinga Canicularis)'. Journal of Comparative Psychology, vol. 117, no. 1, 2003, pp. 87-95. APA PsycNet.

Wright, Timothy F., Angelica M. Rodriguez, et al. 'Vocal Dialects, Sex-Biased Dispersal, and Microsatellite Population Structure in the Parrot Amazona Auropalliata'. Molecular Ecology, vol. 14, no. 4, 2005, pp. 1197-205. Wiley Online Library.

Footnotes

- Manipulative experiments like this, where visual signals can be altered in birds that are then released to behave and interact freely under natural conditions, have provided some powerful insights including the singular importance of UV plumage reflectance (and UV sensitive vision) to mate attraction in many bird species (Hausmann et al.). ↩

- Recent studies in rosellas and other species suggest that olfaction is a much more important means of communication in birds than previously thought. Rosellas have distinctly odorous plumage, and it is now evident that this provides a further modality of communication operating within crimson rosella populations, as well as across the species boundary (Mihailova et al., 2018; Mihailova et al., 2014). ↩

- Considering racism and animality, Syl Ko equates the two with a call to responsibility, suggesting that we extend an anti-racist commitment to animals when we respectfully attend to their lifeworld (Ko, 'Addressing Racism Requires Addressing the Situation of Animals' 47, 48). ↩

- As such, I was unsurprisingly challenged by a lack of access to appropriate material infrastructure supporting a visual intervention into tetrachromia; for example, UV light is dangerous to human viewers in high quantities, and the flicker rates found in standard displays (such as TV or computer screens) are too low to produce a smooth viewing experience for a bird. ↩

- I am thinking, for example, of the many 'undesirable' behaviours that humans seek to manipulate in their domestic companion animals. Myriad industries and publications normalise the control and suppression of certain expressions in the domestic companion animal, such as certain vocalisations or bodily exertions. ↩