Pretty polyglot: parrotisation as the difference in repetition, again.

by Dr Tessa Laird

- View Tessa Laird's Biography

Tessa Laird is an artist and writer who lectures in Critical and Theoretical Studies, Victorian College of the Arts, University of Melbourne.

Pretty polyglot: parrotisation as the difference in repetition, again.1

Dr Tessa Laird

This paper was written on Kulin Country — moving between the unceded lands of the Wurundjeri, Boon Wurrung, and Dja Dja Wurrung peoples. On Kulin Country, birds are powerfully symbolic: Bunjil, the creator spirit, travels as a wedgetail eagle, and Waa, the protector, travels as a crow.2 Even the humble parrots, as Wurundjerri knowledge holder Mandy Nicholson reminds us, are Bunjil's children, and they carry Bunjil's messages, for those who know how to listen.3

The question of how to listen to birds, and how to interpret their messages, has always been of paramount importance, but today, their oracular powers are rarely noticed. Even the Roman Empire governed by paying careful attention to birdlife: formations in flight patterns or the pecking of grain (Serres 99). In marvelling at this charming and surprising example of Roman humility, Michel Serres notes that while birds manage to go about their lives "without consulting us" we have looked to them for guidance and as role models (100). Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers's twentieth century project Department of Eagles lovingly lampooned Rome's obsession with an avian avatar, while Argentinian artist Sergio Vega's twenty-first century update of this work substitutes eagles with parrots.

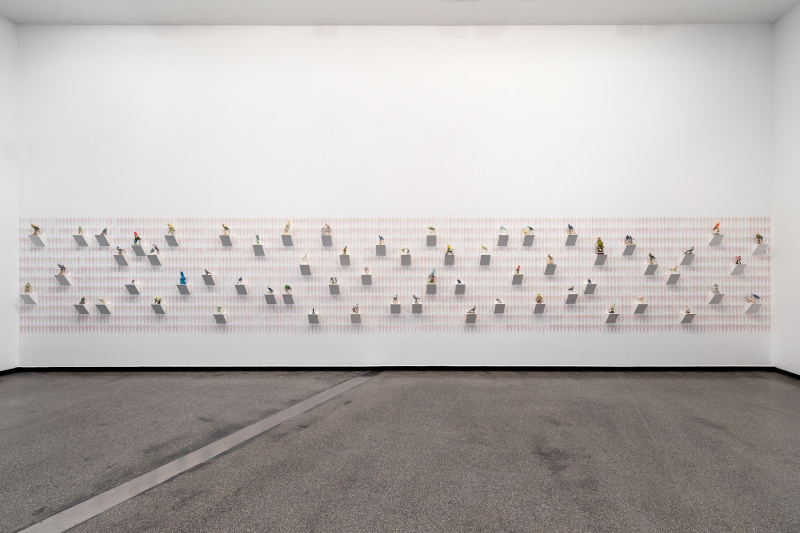

Photo credit: Sergio Vega, Latin American Art Museum, Department of Parrots, 2015. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Photo credit: Sergio Vega, Department of Parrots (detail), 2009, assemblage, variable dimensions. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Following Vega, the parrot will be the abiding avian emblem of this paper, and while I cannot say that I have "consulted" the birds, I have spent many hours watching the antics of rainbow lorikeets in gnarled old fruit trees, and I am performing the strange manoeuvre of self-parroting, by repeating phrases that I have published before (see footnote 1). You might call this self-parroty (with the hard T of self-parodic North Americans). It is difficult to resist wordplay when thinking of the verbally dextrous parrot; "pretty polyglot" is, of course, a riff on the term of endearment "Pretty Polly". Why have parrots been called "Polly" (double L) in Anglophone countries since the seventeenth century? No amount of pecking at the hall of mirrors that is the internet revealed an answer, although Polly is thought to be a form of Molly, which has connotations of a woman of ill repute.4 The name bears no relation to the Ancient Greek prefix "poly" (single L) meaning "many", yet, in the thickest jungles of human art, music and literature, squawks of parrots erupt and echo as emblems of diversity and proliferation, of difference and repetition and of the generation of novelty through wilful reiteration. The reverberations of parodic parrots throughout this paper include, but are not limited to, Julian Barnes's post-modern classic novel Flaubert's Parrot (1984), which eviscerates notions of authenticity; the real-life tale of Alex the African Grey, a lab parrot whose linguistic prowess has fascinated artists and writers; and Jonathan Jones's Untitled (Gidyirriga), (2018), which uses the repeated figure of the budgerigar to enact relationships between biodiversity and language.

Parrots have a propensity for vocal, and even postural, repetition; schooled or unschooled, they can perform uncanny feats of mimesis, sometimes as accurately as a recording device. To be polyglot is to be able to speak many tongues.5 Parrots live in communities of anywhere between 20 to 300 birds, and these communities develop their own unique dialects. Some parrots are truly polyglot, learning to speak more than one dialect (Meijer 72), as well as the languages of other birds, bats, and of course, humans (21).

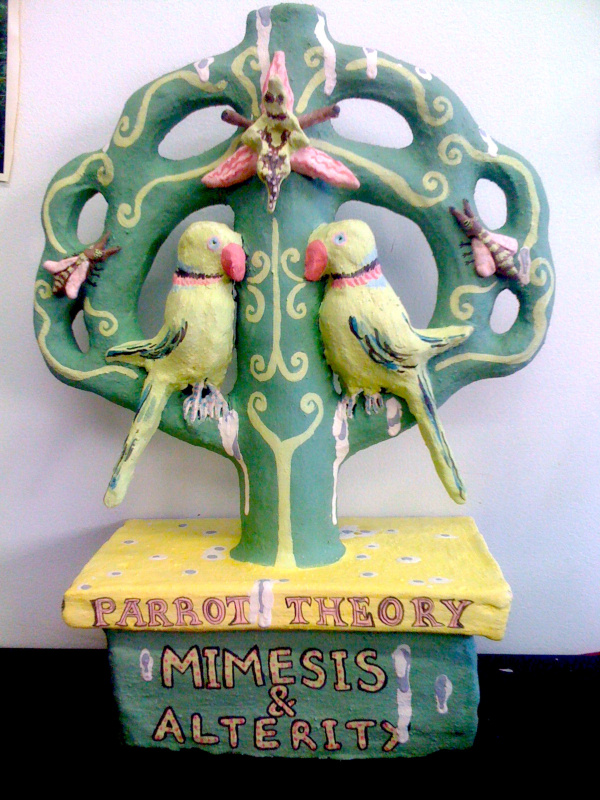

Parrots' linguistic capabilities are celebrated in various folk beliefs, sometimes to the detriment of the birds themselves, as their bodies have been used ritualistically to endow a human subject with the ability to speak in foreign tongues. Michael Taussig's Mimesis and Alterity uncovers the magic of mimicry and its fascination for "the Other", including stories from the Panama region of parrots used in magical rites. Would-be polyglots either eat parrots, or smear the incinerated birds' ashes on their tongues. "It is the soul of the parrot that then does the teaching, and this occurs in dreams, where the parrot's soul may appear as a foreign person"(134-135). This is known as "sympathetic magic" (Frazer 14-62), or, as Félix Guattari puts it, machinic phyla (192), where resonances operate transversally across Western taxonomies. In Taussig's example, difference or alterity (foreign persons and foreign tongues) and repetition or mimesis (language acquisition) are both in play.

When humans mimic these feathered masters-of-mimesis, we co-create a mimetic feedback loop which Taussig gives the heady name "the metamorphic sublime", from which, he says "all manner of being emerges" (Palma Africana 1). The question of who is mimicking whom is moot, as parrots have been on the 'cene (sic) at least 50 million years prior to us apes. As Paul Carter puts it, the pre-human world was not speechless, but "alive with the primary colours of language, clicks, squawks and whistles... a kind of all-speak," (110-111) while D.H. Lawrence pointed out that, "in the beginning it was not a Word, but a chirrup" (57). The American doo-wop group The Rivingtons released "The Bird's the Word" in 1963, perhaps acknowledging the originary "irruption of language in nature"(Lamborn-Wilson 58) that introduced difference into the world.

Artist Sergio Vega reminds us that, when Europeans accidentally bumped into the "new" (ancient) world we now know as Latin America, European theology believed the world to be less than 4,000 years old. It was also thought that parrots could live up to 600 years, and thus quite feasible that some might remember "the lost language of Eden" (37). Is this what The Rivingtons meant by "the bird's the word", an expression of avian Logos? Like many Black groups, they were mimicked/ appropriated by a white one — the surf rock group The Trashmen, who dropped the verses and went straight for the nonsensical chorus.6 Watching The Trashmen's lead singer Steve Wahrer flap his arms like chicken's wings while lip-syncing supports Richard Meltzer's summation of the song's "uncontested vulgarity" as a sign of rock 'n' roll's growing self-consciousness of its own "base and vulgar nature" (103). Though Meltzer only wrote a single sentence on the song, he painstakingly transcribed every syllable of its lyrics, making them the frontispiece to his book The Aesthetics of Rock. In repeating the repetitive, The Trashmen took the stuttering echolalia of "A-well, a bird, bird, bird, bird is a word" and turned it into what Kodwo Eshun called (in relation to early hip-hop) the "stammer of the new" (16); when a seemingly puerile novelty breaks down and remakes semiotics, questioning the relationships between birds and words, or words and anything, with the insistence of an enraged woodpecker.

Given the ancient avian origins of language, the fact that we presume to teach parrots to speak is an act of mimetic doubling, deflecting attention, like light off a mirror, from the possibility that they taught us to speak. One of the most famous examples of psittacine linguistic prowess was Alex the African Grey parrot, who knew close to 150 human words. He could count objects, separate them into categories, make jokes and express frustration at repetitive tasks, as well as surprise and anger when they changed (Meijer 20). Like most people, difference and repetition made Alex cranky. He was bought from a pet shop at the age of one but his name, far from being an appellation bestowed upon a beloved pet, was an acronym for "Avian Language Experiment". He spent 30 years in captivity before dying a relatively premature death for a parrot.

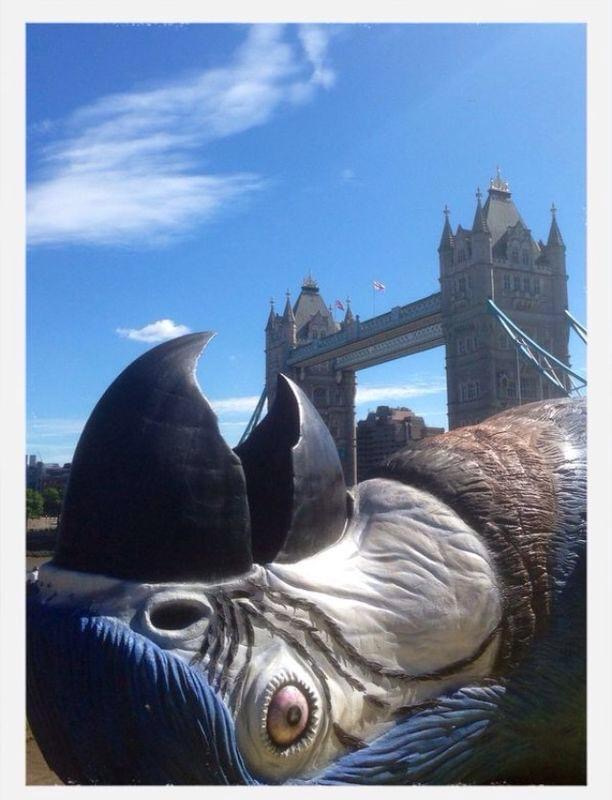

Alex's life story resonates dolefully with the classic Monty Python "Dead Parrot Sketch", in which John Cleese as the outraged customer attempts to return the deceased parrot he was sold by Michael Palin as a dodgy pet store owner. Cleese intones: "This parrot is no more, it has ceased to be, it has expired and gone to meet its maker. This is a late parrot... an ex-parrot" (Halberstam 115-116). While Alex was technically alive, he is emblematic of what Jack Halberstam refers to as our "zombified" relations with animals (116). Halberstam invokes both the "Dead Parrot Sketch", and its giant sculptural tribute by Iain Prendergast (2014) to ask whether in fact "all pets are always already dead", that is, "barely living and existing only according to the dictates of a human master" (162).

Photo credit: Iain Prendergast, Dead Parrot, 2014 (detail). Fibreglass, 49 ft long. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Photo credit: Iain Prendergast, Dead Parrot being installed in Potters Field Park, London, 2014. Photo courtesy of the artist.

For Halberstam, it is not only the parrot that is dead, but the humans who insist on controlling and training animals, just as they too are controlled and trained by the capitalist colonialist heteropatriarchal state. Halberstam considers the "Dead Parrot Sketch" to be the "perfect symbol of our time... in which we are all already late, deceased, ex-humans masquerading as resting, stunned, or momentarily incapacitated" (116).

Zombies have long been associated with capitalism7 and in the "Dead Parrot Sketch", what is being sold is a parroty parody of commodity fetishism. The parrot cannot be exchanged, and is therefore of symbolic value only, though it performs its function just as well as a live one (sitting in a cage and essentially playing dead). While the parrot may once have had the role of sonic entertainer, we now have television, radio, and stereo for that... (not to mention Twitter and other social media platforms which take parroting as their model — more on this later). No wonder Alex plucked himself, a symptom of stress in incarcerated birds. Perhaps riffing on the idea that a bird is a word, Carter says, "Feathers are letters, and when it becomes plain that no amount of erudition can earn the parrot his freedom, he grows melancholy. He refuses to speak; he tears off his armature of feathery phrases, and stands naked and trembling" (99). The naked, trembling Alex reflects our own carceral reality back at us (Halberstam 119).

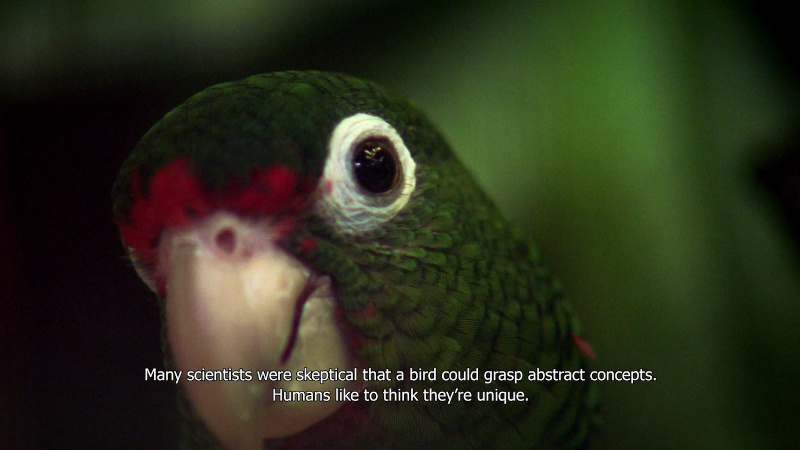

We need to listen differently to our feathered kin, imagining communication, Carter suggests, as a "net" or "open web", rather than cage or other "technique of enslavement" (8). Only then will the Eden from whence the parrots came reveal itself. But as collaborative artist duo Allora and Calzadilla demonstrate with their 2014 video work The Great Silence, made in collaboration with science fiction author Ted Chiang, even at the heart of Eden (or the jungles of Puerto Rico), humans can be oblivious to the teachings of parrots.

Photo credit: Allora and Calzadilla, The Great Silence, 2014, Film still. Three-channel HD video installation. Dimensions variable, 16 minutes 22 seconds ©Allora and Calzadilla. Courtesy Lisson Gallery.

The Great Silence juxtaposes footage of the imposing dull-grey structure of the Arecibo Observatory with shots of the sparkling emerald jungle that surrounds it. Arecibo, like humans and parrots, is both a receiver and transmitter, yet it remains "silent" throughout the video, apart from its ominous hum. No human speech is vocalised, but parrot speech animates the jungle, accompanied by a text written from the perspective of these endangered birds. The parrots (or rather, human writers imagining themselves as parrots) ask why this giant ear of Arecibo is trained towards the skies, when they, the parrots, are "right here"? Terrestrial parrots are a non-human species capable of communicating with humans — so why are not humans listening, instead of courting aliens who may not even exist? The incapacity to notice and value what is under our noses could have dire consequences. The term "Great Silence" is used to explain why the night sky is as quiet as a graveyard when it ought to be as cacophonous as a healthy jungle (Alora and Calzadilla and Chiang). Some scientists believe the extinction of intelligent species could have taken place before they were able to take to the skies, while Carter suggests "Our culture...is systematically pursuing the extinction of its own totem" (8). The final message from the endangered Puerto Rican parrots, is: "You be good. I love you," which is what Alex the parrot said to his friend and jailor Irene Pepperberg the night before he died (Alora and Calzadilla and Chiang).

How do we listen to parrots differently, to avoid zombified relations? We must first understand the mimetic faculty not as mindless repetition, but as "the nature that uses culture to create second nature, the faculty to copy, imitate, make models, explore difference, yield into and become Other" (Taussig Mimesis, xiii). Enjoying this heady repetition, Taussig notes that he is doing it too, writing of Cuna Indians whose chants involve a series of quotations within quotations, while he is quoting another anthropologist, while I am now quoting Taussig, and so on, ad infinitum, "doubling mimetic doubling" (110). Truly, these are copies without an original, as Jean Baudrillard would have it, but who was only ever parroting what the parrots were telling us all along. Baudrillard's "precession of simulacra", in which the copy precedes the original, is an idea which precedes Baudrillard and can be found in Gilles Deleuze paraphrasing Charles Péguy to the effect that "it is not Federation Day which commemorates or represents the fall of the Bastille, but the fall of the Bastille which celebrates and repeats in advance all the Federation Days; or Monet's first water lily which repeats all the others" (Khang 19).

In Flaubert's Parrot, Julian Barnes renders French nineteenth century novelist Gustave Flaubert more enigmatic by repeating hearsay, mediated by an alter-ego; a retired doctor-come-Flaubert-enthusiast who spends his leisure time sniffing out traces of the novelist in historical Rouen. The titular parrot refers to a stuffed bird Flaubert loaned from the local museum for inspiration. It sat on his desk as he wrote Un Coeur Simple (A Simple Heart, 1877), about Félicité, a servant, and her pet parrot Loulou, whom she has stuffed after his death. Félicité says her prayers while kneeling before this ex-parrot, and begins to wonder if the Holy Ghost, often portrayed as a dove, should instead find psittacine incarnation, after all, parrots have the ability to speak the word of God, whereas doves have no Logos. Indeed, when Félicité dies and ascends to heaven, she perceives "a gigantic parrot hovering above her head" (Barnes 17).

To write his story with some degree of authenticity, Flaubert lived for weeks with a stuffed parrot perched on his writing desk, "staring back at him like some taunting reflection from a funfair mirror" (18). Flaubert found the ex-parrot supremely irritating, and Barnes wonders if this was because it forced him to recognise that writers are little more than "sophisticated parrot(s)" (ibid). Perhaps Barnes's title is less about the stuffed bird on Flaubert's desk than a dig at himself, who in writing the book does little more than repeat everything he has heard about Flaubert? This trope of redundancy is redoubled by the fact that there are two stuffed parrots in Rouen claiming to be the one which inspired Flaubert to write Un Coeur Simple. Later, Barnes reveals that these birds were both sourced from a flock of 50 at the Museum of Natural History.

It seems fitting that this tale of (in)authentic copies takes place in Rouen, whose Cathedral was the subject of a series of 30 paintings by Monet of which 20 were shown together in 1895 in an unprecedented display of difference and repetition, at least, in the West (Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai created his 36 Views of Mt Fuji between 1830 and 1832). British artist and curator John Coplans argued that Monet's various series invented the concept of "seriality" in art (7), ushering in modernity or perhaps even postmodernity. In 1968 Coplans curated the landmark exhibition Serial Imagery at the Pasadena Museum of Art, which inspired Roy Lichtenstein to silkscreen copies of Monet's Rouen Cathedral series (LACMA). While Barnes's narrator feels discomfort at the image of the writer-as-parrot, who "feebly accepts language as something received, imitative and inert" (19), Coplans wrote that Serial Imagery's "redundancy" was a "positive act that continuously affirms the power and continuity of the creative process" (Kahng 15-16).

Flaubert's own fascination with doubling and mimicry is evident in his posthumous Bouvard et Pécuchet (1881), whose eponymous characters are two Parisian copy-clerks who mirror each other. Their life's work is to make psittacine repetitions in a Dictionary of Received Ideas, "an enormous dossier of oddities" sourced from press clippings compiled by Flaubert, referred to as "La Copie" (Barnes 57). One clipping from 1863 tells the story of Henri K. whose parrot repeated the precious name of Henri's lost lover. When the parrot died, Henri became the parrot, squawking the beloved's name, walking like a parrot, and flapping his arms as if they were wings (58), prefiguring the lead singer of The Trashmen by exactly 100 years.

Deleuze acknowledges the repetitive, mimetic artworks of Andy Warhol as "not simple imitation but the act by which the very idea of a model or privileged position (an original) is overturned" (Ganis 92). Deleuze's Difference and Repetition was published in 1968, the same year as Coplan's Serial Imagery show, and has been described as both symptomatic and diagnostic of the times (Fer 2). But let us look at something else happening in 1968, more suited to the tropical climes of parrots than Warhol's New York or Deleuze's Paris: the Dub (short for doubling) coming out of Jamaica. In his brilliant radio series The Strangeness of Dub, artist and writer Edward George notes that King Tubby was making "versions" (using engineering wizardry to cut multiple disks from the same song) in 1968, while Deleuze's Difference and Repetition was being published. George suggests that Deleuze was "versioning" Sigmund Freud's ideas of repetition, but unlike the psychoanalyst's prognosis that repetition was a form of compulsive denial of past trauma, Tubby's music, akin to Deleuze, asked listeners — "what if repetition wasn't such a bad thing? What if each repetition had a wonderful piece of difference all its own?" (Episode 4). When discussing the works of Lee "Scratch" Perry, George refers to "the difference in repetition by which versioning takes place" (Episode 6), noting that versioning destabilises the God's eye view, even and especially, we might version on George, if that god is a giant parrot.

Kodwo Eshun describes Lee Perry's echo chamber as housing the "ghosts of ghosts of effects, 5th generation fx, unforeheard screams, rattles and rustles" (64). The echo changes the mode of listening, "Your ear has to chase the sound... it becomes this series of retreating echoes... The beat becomes a tail which is always disappearing round the corner..." This sounds like Barnes's characterisation of the past as "the flash of a parrot, two mocking eyes that spark at you from the forest" (112). Repeating a motif is not dull or stupefying; according to Eshun it makes the listener work harder, "turn(ing) listening into running" (64). For Eshun, 1968 also marks the year versions started coming out of Jamaica, and Walter Benjamin's "single, unique aura" has gone out the window, where, "you've got this thing that's never supposed to exist in Benjamin's world: you've got the one-off copy... you've got the one-off twentieth remix" (188). In this vertiginous mis-en-abyme of industrially reproduced sound, "the aura is reborn" (ibid). Eshun's maxim "Degeneration = Regeneration" (66) means the parrot that repeats a motif until its disintegration and rebirth as noise is not a mechanical nightingale but a phoenix, rising from the ashes of originality.

Repetition should not be denigrated, for "What organism is not made of elements and cases of repetition?" (Deleuze, DR, 75). This holds true right down to cellular division and genetic code. Perhaps visualising a budgie eating a spray of millet, Deleuze calls repetition "the external husk of a kernel of difference and more complicated internal repetitions" (76). Difference lies between two repetitions (Roffe, 159), or, two seemingly identical millet seeds. Attuning to the force of such imperceptible variation, Erin Manning mobilises a "politics of the infrathin", of that which is "not seen within the seeable" (15) and, we could surmise, not heard within the audible.

In her discussion of repetition in the literature of Gertrude Stein, Astrid Lorange writes that "Being insistently and with deviation is becoming: an emergent ontology" (19). Stein's singularity as a writer is most often attributed to her fearlessness regarding verbal repetition, but Lorange argues that for Stein, repetition cannot exist: "in the act of repeating, the thing repeated is never the same — its 'emphasis' will always and necessarily be different. Thus 'repetition' is a kind of insistence and continuous repeating is the minimal modality of differentiation" (206). Stein's investment in repetition-as-difference chimes with Deleuze's Difference and Repetition, which argues for repetition "as the principal agent of change", in which "variations (in form, intensity, volume, mood, and so on) are registered" in a process by which they become-other (207). Stein invokes the figure of a bird singing as "the nearest thing to repetition" but, she says, if you listen "they too vary their insistence" (209). No matter how many times a thing happens, Stein suggests, there is "no repetition" as such, and she relates this to what William James calls the "Will to Live" without which "nobody would live" (207-8).

Alex must have lost his will to live, because when asked the difference between two objects which appeared the same, he said "none", which was the desired answer, and led to a nutty reward. But deep down he must have known there is no such thing as repetition, and that a world of difference exists between two plastic cups. Like the authorities responsible for selling off the Murray Darling's water, Alex sold his soul for almonds.8 This may have led to an existential crisis. Gazing into a mirror, he asked "what colour"? and learned he was "grey". Goethe equated theory with the colour grey (Batchelor, 69), and Alex was just that, a theorem, not an animal, exactly the abstraction Jacques Derrida warned against (383). Alex died of a broken heart — realising that he was nothing but a grey mirror held up to humanity.

We give parrots mirrors to play with, laughing at their seeming simplicity as they peck imaginary adversaries, or sweet-talk themselves. In these acts of paranoia and narcissism, the parrot mirrors the human (Carter, 8), yet we call them vain. Flaubert wrote Pride "is a wild beast which lives in caves and roams the desert", while Vanity "is a parrot which hops from branch to branch and chatters away in full view" (Barnes, 59). John Berger understood this phenomenon of scopophilic deflection, noting that throughout the history of Western art, mirrors were hypocritically used to symbolise women's vanity (51). Addressing the heterosexual male "art lover", Berger says: "You painted a naked woman because you enjoyed looking at her, you put a mirror in her hand and you called the painting Vanity, thus morally condemning the woman whose nakedness you had depicted for your own pleasure" (ibid). If the function of the mirror was to make women connive in their own depictions, could we replace "woman" with "parrot" and "painting" with "cage", versioning Berger to remember once again that the subjugation of women goes hand-in-claw with the subjugation of animals? The double shadows woman as much as it does Pretty Polly: she can only survive patriarchy by being "split into two", that is, "almost continually accompanied by her own image of herself" (46) as if she was gazing into a mirror without one being present.

The split self, however painful, is also a site of creative production. For Taussig, the mimesis of mirroring is "unsettled and unsettling interpretation in constant movement with itself" in which the "self enters into the alter against which the self is defined and sustained" (Mimesis 237). He describes this as "a kind of electricity, an ac/dc pattern of rapid oscillations of difference". Pushed to the limit, mimesis becomes alterity, and only then "can spirit and matter, history and nature, flow into each others' otherness" (192). The parrot's mirror is a window into a world of alterity, such as the one Alice finds in Through the looking glass. According to Deleuze we need to step through the mirror to appreciate the dynamism and complexity of the world, where concepts are tested for their reverse capabilities (Roffe 251-252). In this mirror-world, there is no opposition between being and becoming, change and stasis. What appears to stay the same must be understood in a radically differential fashion, like Stein's, or any self-respecting parrot's, repetition.

Imagining a world through the looking glass is a little like imagining the world through parrot vision. Not only would we see more colours, but a more-or-less 360-degree view. Released from our current "perspectival cage", we would witness a world "without centre or edge" (Carter, 157). Since parrots see one side of themselves with one eye, and the other side with the other eye, they have no "stereoscopic synthesis", no single unified image of themselves, no concept of possessing a single identity (156). Far from being a split subject in a negative sense, parrots are dividual rather than individual. Brian Massumi uses this term when discussing the birds in J. A. Baker's The Peregrine (1967), calling each "a multiplicity of qualitative fissions and fusions continually varying its figure. Not a particular, but a singular self-populating" (85). Parrots are social creatures for whom identity is never fixed, and subjectivity a diffractive affair. Sergio Vega regards them as the perfect emblem for the twenty-first century. Vega's Telephones of Paradise series documents Brazilian public payphones fashioned as giant parrots, and he made copies of these phones for the 2005 Venice Biennale.

Photo credit: Sergio Vega, June 1, 2005, Venice Biennale, from Telephones of Paradise. Photo Jason Schmidt.

There is something unequivocally totemic about Vega's plastic emblems of communication, through which people send squawks and shrieks across the world. Reversing Taussig's story of Panamanians who turned parrots' ashes into language, Vega writes the parrot is busy "Turning language to ashes" (4). While parrots mimic human language, the disruptive power of their shrieks tear away at humans' sentimental attachment to meaning like a flock of cockatoos decimating an almond tree.

Photo credit: Marcel Broodthaers, Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles, 1968. Wikiart, Fair Use.

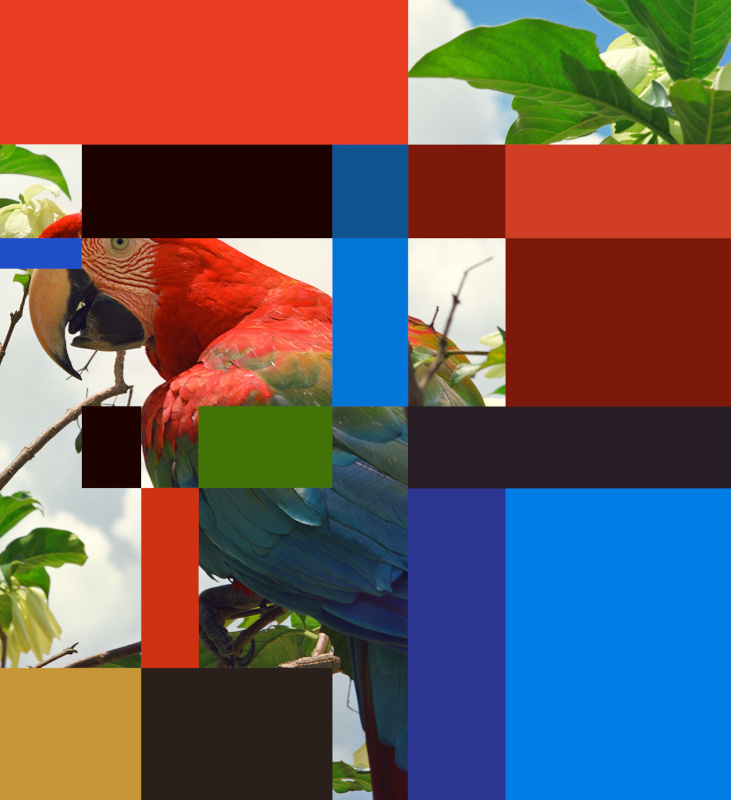

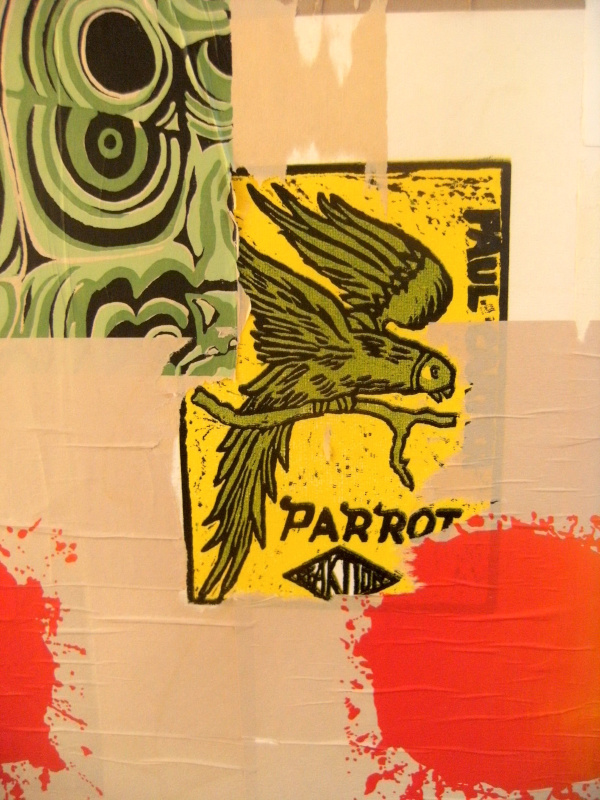

Vega's parrots are a pointed response to Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers's Museum of Modern Art, Department of Eagles, (also founded in that critical year, 1968). Broodthaers collected around 500 objects of memorabilia with eagle insignias and presented them in a parody of museological display. His choice of the eagle, with its connections to Imperial Rome, Nazis, and the United States, was doubtless a mode of political critique. Vega takes up where Broodthaers left off, making deliberate references to his predecessor by creating a Latin American Art Museum, Department of Parrots, displaying his own collection of parrot memorabilia and developing the manifesto "Parrot Theory", declaring that "the days of the hierarchical and lonely eagle are over", and the era of the parrot — and greater parity (as well as parody) — has begun.

Photo credit: Sergio Vega, El loro de Borges (Borges' parrot), 2009, mixed media assemblage. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Vega's parrot knocks the eagle off its perch, so to speak, as the South throws off the shackles of the colonising North. He compares parrots to "flocks of immigrants from the warm regions of the world" who bring with them spices and colours, are communal and communicative, and "have a great propensity to learn from others" (46-47). Vega presents numerous psittacine incursions into the Western canon of art history, from a copy of the Winged Victory of Samothrace modelled with bright green parrot's wings, to Mondrian-like grids in which photographs of parrots jostle for space amidst primary-coloured rectangles.

Photo credit: Sergio Vega, Parrot Colour Chart, 7B, 2010, inkjet print. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Also using parrot imagery to challenge patterns of cultural influence along the North-South axis, Wiradjuri and Kamilaroi artist Jonathan Jones's Untitled (Gidyirriga) (2018) mobilises kitsch memorabilia as a subversive tactic. Jones pays tribute to the Australian parrot that is the third most popular pet globally after cats and dogs, through visual and vocal repetition. A colourful collection of ceramic budgerigars gathers against a patterned wall, and a soundtrack of human voices — Wiradjuri and non-Aboriginal children learning the Wiradjuri word gidyirriga — plays over these artificial avians. While such ornaments are usually shown as individual items or pairs on a mantel piece, here Jones assembles a massive flock, in homage to the social nature of the budgerigar in its natural habitat. The wall itself is hand-stencilled in a pattern that refers to south-east cultural markings, but also evokes the vintage wallpaper of a mid-century modern living room.

Photo credit: Jonathan Jones, Untitled (gidyirriga) 2018, ceramic figurines, sponge-stamped synthetic polymer paint, wood, stereo, soundscape, dimensions variable, installation view, A Lightness of Spirit is the Measure of Happiness 2018, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Sound design: Luke Mynott, Sonar Sound; Voices Karma Dechen, Renna Dechen, Beth Delan, Jenson Howard, Lilia Howard, Taj Lovett, Mincarlie Lovett, Phoebe Smith, Ben Woolstencroft and Mae Woolstencroft from Parkes Public School; with thanks to Uncle Stan Grant Snr AM, Uncle Geoff Anderson and Lionel Lovett. Courtesy of the artist. Photograph: Andrew Curtis.

Photo credit: Jonathan Jones, Untitled (gidyirriga) 2018 (detail), ceramic figurines, sponge-stamped synthetic polymer paint, wood, stereo, soundscape, dimensions variable, installation view, A Lightness of Spirit is the Measure of Happiness 2018, Australian Centre for Contemporary Art, Melbourne. Sound design: Luke Mynott, Sonar Sound; Voices Karma Dechen, Renna Dechen, Beth Delan, Jenson Howard, Lilia Howard, Taj Lovett, Mincarlie Lovett, Phoebe Smith, Ben Woolstencroft and Mae Woolstencroft from Parkes Public School; with thanks to Uncle Stan Grant Snr AM, Uncle Geoff Anderson and Lionel Lovett. Courtesy of the artist. Photograph: Andrew Curtis.

Jones writes that "The word 'budgerigar', like many Australian words, is a corruption of an Aboriginal word. In Wiradjuri we call them gidyirriga" (n.p.). Colonists and global bird enthusiasts have mangled both the name and the form of the bird. The infinite "reproducibility" of the budgie has, of course, led to "mutations", and Jones notes that the mass-production of the birds via ceramics moulding has also caused modifications, where details are lost or exaggerated, so the birds have become "imaginary depictions". Jones makes an analogy with Aboriginal knowledges, which have also been "duplicated, mutated, disrespected". Yet as Jones points out, it was his Wiradjuri great grandmother who instilled in him a love for such ceramic figurines. Nonetheless, Untitled (Gidyirriga)'s candy-coloured glory would be no match for a murmuration of real budgies in the grasslands of arid inland Australia. As Barnes puts it, "Ironies breed" while "realities recede" (70).

Jones's work begs the question, when do mutations that inevitably result from reproduction add value and novelty to the world, and when do they diminish or debase? Carter is filled with anxiety about parrotization, which he characterises as a "cosmos of inscrutable hearsay, anecdote, opinion" (175) signalling the death knell of genuine research. For Carter, psittacine eloquence runs the risk of collapsing into noise; superficial, universalised ignorance. Social media and instant access to self-publishing fuel Carter's critique. In Vega's "Parrot Theory", however, information technology's "parrotization of culture" is characterised not so much by the banal twitter of social media platforms, but by information sharing within a cultural commons.

Photo credit: Tessa Laird, Parrot Theory, 2014. Photo courtesy of the artist.

Photo credit: Tessa Laird, The Milky Ocean / The Fiery Pool (detail), 2012. Photo courtesy of the artist.

This "difference without separability" (Ferreira da Silva) is a gathering of "rainbow alliances" (Carter, 144) which Vega visions as "the rise of a global, postcolonial avant-garde forever changing the world into words, mirrors, and colours, as we speak..." (17). Even Carter is prepared to see things differently: in this "network of parroternalia", coherent threads emerge, weaving a pattern that constitutes a "kind of knowledge" (176). Perhaps, ditching the term "research", which after all bears indelible traces of colonialism and is a dirty word in Indigenous vocabularies (Smith, 1), we could instead, following Harney and Moten, call Carter's "kind of knowledge" a form of "study"? Study is "talking and flapping around with other parrots, eating berries, singing, some irreducible convergence of all three, held under the name of speculative practice..." (Harney and Moten, 110, version).

Parrots are full of words, but this paper has a strict word limit. While the references to parrots could (and do) go on, this paper must stop. Therefore, and at the risk of seeming psittacine in my repetition of phrases without context, I wish to finish with two quotes on difference. Repeating Edouard Glissant's "Poetics of relation", Erin Manning says, we do not need to ask: "relation between what and what?" Rather, Manning emphasises, "Diversity is in diversity, not in opposition to a norm" (4). And, as Gertrude Stein writes in Tender Buttons, echoing the movement of Vega's flocks of psittacine immigrants, this "difference is spreading" (3).

Works Cited

Alora and Calzadilla and Ted Chiang. "The Great Silence." Supercommunity, e-flux journal, 56th^ Venice Biennale, May 8, 2015,

Barnes, Julian. Flaubert's Parrot. London: Cape, 1984.

Batchelor, David. The Luminous and the Grey. Reaktion Books: London, 2014.

Baudrillard, Jean. Simulacra and simulation. Translated by Sheila Faria Glaser. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1994.

Berger, John. Ways of Seeing. London: Penguin Books, 1972.

Carter, Paul. Parrot. London: Reaktion, 2006.

Coplans, John. Serial Imagery. CA: Pasadena Art Museum, 1968.

Deleuze, Gilles. Difference and Repetition. Translated by Paul Patton. New York: Columbia University Press, 1994.

—. The Logic of Sense. Translated by Mark Lester with Charles Stivale. New York: Columbia University Press, 1990.

Derrida, Jacques. "The Animal That Therefore I Am (More to Follow)." Critical Inquiry, Vol. 28, No. 2, Winter, 2002.

Eshun, Kodwo. More Brilliant Than the Sun: Adventures in Sonic Fiction. London: Quartet Books, 1998.

Fer, Briony. The infinite line: remaking art after modernism. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2004.

Ferreira da Silva, Denise. "On Difference Without Separability", 32nd Bienal De São Paulo Art Biennial: Incerteza viva. Sao Paulo: Fundaçao Bienal de São Paulo, 2016.

Frazer, J.G. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion. Suffolk: The Chaucer Press, 1974.

Ganis, William V. Andy Warhol's Serial Photography. New York: Cambridge, 2004.

George, Edward. The Strangeness of Dub, Morley Radio.

Guattari, Félix. Chaosophy: Texts and Interviews 1972 - 1977. Los Angeles, CA: Semiotext(e), 2007.

Harney, Stefano, and Fred Moten. The Undercommons: fugitive planning and black study. Port Watson: Minor Compositions, 2013.

Jones, Jonathan. "UNTITLED (GIDYIRRIGA)", Jumbunna Research, 2018, .

Khang, Eik (ed.) The repeating image: multiples in French painting from David to Matisse. Baltimore: Walters Art Museum, 2007.

LACMA (Los Angeles County Museum of Art), "Monet / Lichtenstein: Rouen Cathedrals".

Lamborn-Wilson, Peter. "Green Hermeticism", Green Hermeticism: Alchemy and Ecology, edited by Christopher Bamford. Massachusetts: Lindisfarne Books. 2007.

Lawrence, D.H., Etruscan Places. London: William Heinemann Ltd., 1932.

Lorange, Astrid. How reading is written: a brief index to Gertrude Stein. Connecticut: Wesleyan University Press, 2014.

Low, Tim. Where song began: Australia's birds and how they changed the world. Melbourne: Viking, 2014.

Manning, Erin. For a pragmatics of the useless. Durham: Duke University Press, 2020.

Massumi, Brian. "Becoming-Animal in the Literary Field". Couplets: Travels in Speculative Pragmatism. Durham: Duke University Press, 2021.

Meijer, Eva. Animal Languages. Translated by Laura Watkinson. Cambridge, MASS.: The MIT Press, 2019.

Meltzer, Richard. The Aesthetics of Rock. New York: Something Else Press, 1970.

Roffe, Jon. The works of Gilles Deleuze, Volume 1, 1953-1969. re.press: Melbourne, 2020.

Serres, Michel. The Five Senses: a philosophy of mingled bodies (I). Translated by Margaret Sankey and Peter Cowley. London; New York: Continuum, 2009.

Smith, Linda Tuhiwai. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London; New York: Zed Books, 2012.

Stein, Gertrude. Tender Buttons. New York: Dover Publications, 1997.

Taussig, Michael. Mimesis and Alterity: a particular history of the senses. New York: Routledge, 1993.

—. Palma Africana. Chicago; London: The University of Chicago Press, 2018.

Vega, Sergio. Parrot Theory. Paris: Galerie Karsten Greve, 2009.

Footnotes

-

Part of this title comes from Gilles Deleuze's foundational Difference and Repetition (1994). "Again" refers to the fact that I presented an earlier version of this paper at the Birds and Language Conference, and a shorter version of this text was published in Art Monthly Australasia (November 2021). Moreover, echoes of these parroty concepts can be heard all the way back in the Green chapter of my book A Rainbow Reader (2013). Appropriately to parrots' propensity for mimicry, this paper has doubled in size since the Art Monthly version, allowing for more bells, trills and whistles, more "parroternalia" (Carter, 67). ↩

-

This knowledge was offered to staff and students at Victorian College of the Arts, Faculty of Fine Arts and Music, University of Melbourne, by Boon Wurrung Elder N'arweet Dr Carolyn Briggs AM, at numerous formal events since I started teaching there in 2015. ↩

-

Nicholson in a speech at the launch of the spACE betWEen us, TAUTAI x Blak Dot, Blak Dot Gallery, Brunswick, November 15, 2019. ↩

-

"Polly, n.1". OED Online. June 2022. Oxford University Press (accessed August 09, 2022). ↩

-

It is worth noting here that the original mimics, if that is not an oxymoron, are the Australian lyrebirds. According to Tim Low, (2014) they are the most ancient songbirds, preceding other evolutionary forms by millions of years. Mandy Nicholson has words of wisdom to share on these amazing ur-birds: people love them because "they speak everyone's language". Nicholson made this observation at the formal celebration for Emu Sky, curated by Zena Cumpston at Old Quad, University of Melbourne, on March 10, 2022. ↩

-

Thankfully, in this instance, The Rivingtons got royalties, while The Trashmen only had performing rights. See: "Surfin' Bird: The Trashmen", Songfacts. ↩

-

This term has been used in Marxist texts such as Chris Harman's Zombie Capitalism: global crisis and the relevance of Marx, London: Bookmarks Publications, 2009, and is a frequent theme in texts examining the symbolic meaning of the zombie in contemporary fiction, see Zombie theory: a reader, edited by Sarah Juliet Lauro, Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2017. ↩

-

See Daniel Pedersen, "Almonds guzzle water from Murray Darling Basin". Green Left, Issue 1320, September 21, 2021, greenleft.org.au. ↩