Of Birds and Men: Migrant Labour and the Avian Subjects of Robert Zhao

by Louis Ho

- View Louis Ho's Biography

Louis Ho is a curator, critic and art historian based in Singapore.

Of Birds and Men: Migrant Labour and the Avian Subjects of Robert Zhao

by Louis Ho

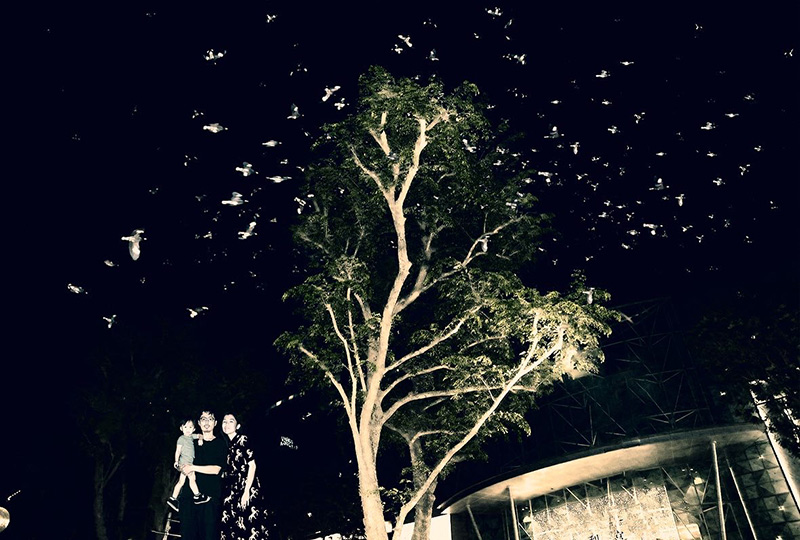

We begin with the juxtaposition of an image, and an incident. The first is Robert Zhao's And A Great Sign Appeared (Thailand-Singapore), part of a similarly titled series of photographic works that looks at the effects of urbanisation on avian colonies in Singapore.1 A bichromatic digital image, it foregrounds a large congestion of diminutive shapes that forms a towering cumulus cloud, looming over the landscape like the titular omen.

Photo credit: And A Great Sign Appeared (Thailand-Singapore) (2021), Robert Zhao. Image courtesy of the artist

The shapes, up close, reveal themselves to be a flock of birds clustered in a cyclonic swirl, a commonly witnessed phenomenon among avian breeds that utilise thermal drafts for upward lift. A distinctively curved lower mandible serves as a clue to their particular species. "Hundreds of Asian openbill storks were spotted flying over the Kranji Marshes on Saturday morning (Dec 7) — an unusual sighting of a bird that usually forages in the rice fields of countries like Thailand", a newspaper article proclaimed in December 2019.2 And A Great Sign Appeared references this unusual avian visitation to the island's shores, capturing images of the storks' (Anastomus oscitans) appearance in Singapore in late December that year. "Thailand had been in the grip of an unseasonable drought", Zhao writes, "and the birds were looking for a more hospitable environment in which to live. Their appearance in Singapore reminds us that our region is connected ecologically, and that climate change has a transnational impact".3 The "great sign" of the title, then, seems to allude to the symptomatic character of the event — a localised occurrence that foretells broader shifts in the region's ecosystems.

Several months later, during the first phase of the COVID-19 pandemic in Singapore, in the midst of a quasi-lockdown that saw the general populace confined to their homes and allowed out of doors only to purchase food, an outbreak of the virus raced through the island's migrant worker dormitories. These dormitories housed a sizeable community of low-wage labourers, largely employed in the construction and manufacturing sectors and hailing from South Asia, especially southern India and Bangladesh.4 The quarters were cramped, self-contained compounds located in outlying areas and housing up to thousands of individuals, often in rooms of more than ten occupants, with only communal bathroom and cooking facilities available. Conditions were ripe for the unimpeded transmission of the virus — and transmit, it did. A dramatic uptick in the number of new infections, beginning in April 2020, was reported: "Cases among workers living in dormitories had surged, alarmingly, from 31 in April 2020 to over 15,000 in May, before more than doubling to 33,000 in June. For much of the year, they made up 19 in 20 cases, and by the end of last year [2021], over 175,000 out of 323,000 dormitory residents had caught the virus".5 The magnitude of the crisis led The Washington Post, for one, to declare that "Singapore lost control of its Coronavirus outbreak, and migrant workers are the victims."6 By the time the mini-epidemic began tapering off in the waning months of 2020, the government was busy constructing new dormitory facilities, with improved hygiene standards and caps on occupancy numbers.

The two episodes would seem, on the surface, to share little in common. The first is premised on an incidence of the animalian; the other, a disruption of the island-state's narrative of careful crisis management during the worst global contagion in living memory. The feathered migrants were greeted by reactions of curiosity and bemusement, while their human counterparts were viewed by segments of the public as misbehaving foreigners, responsible for a breakdown in public health that blemished Singapore's reputation on the international stage. One particularly egregious instance of open antagonism involved a letter published in Singapore's widest circulating Chinese-language daily, Lianhe Zaobao, in which the writer pointed to the personal hygiene and habits of South Asian migrant labourers as the likely cause of the outbreak in the dormitories, and suggested they shoulder the blame for their own predicament.7 Yet, a closer comparison of the discourse that emerged around these events suggests an equivalence between these human and nonhuman communities, and, more to the point, the modes of alterity that underlie them. It is in Zhao's engagement with Singapore's avian fauna, in particular, that the ideological and ethical positions of man and animal meet, affording a measure of suggestive, oblique contiguity between otherwise disjunct narratives. By situating his practice within the realities of twenty-first century Singapore, the convergence between the biologically inferior (nonhuman animals) and the socially disempowered (human actors) is made clear. Reading Zhao's work within its socio-historical context foregrounds the analogy between the nonhuman and less-than-human, an intersection of specific vectors of power that govern the discursive construction of avian and human migrant alike, one other-ed group evoking the next. As we shall see, these affinities are marked by both the language of cross-species metaphorisation, and the redolence of silence. The lives of birds, framed coevally, echo the lives of men.

Echoes

That the appearance of the openbill storks in Singapore did not occasion widespread concern and/or disapprobation seems to have been a function of the transience of their stay; other migrant breeds certainly provoked very different reactions, as did specific communities of non-avian migrants. Implicit here is the notion of speciesism, defined by academic and animal rights activist Peter Singer as "a prejudice or attitude of bias in favor of the interests of members of one's own species and against those of members of other species."8 Singer, of course, was interested in unravelling the lines of differentiation separating human and nonhuman animals, but, just as significantly, his argument against the arbitrary asymmetry of the speciesist complex was equated with forms of human, social discrimination; speciesism was modelled on the prevailing "ism"-s of racism and sexism. "Racists violate the principle of equality", he wrote, "by giving greater weight to the interests of members of their own race ... Sexists violate the principle of equality by favoring the interests of their own sex. Similarly, speciesists allow the interests of their own species to override the greater interests of members of other species."9 There are multiple, intersecting axes of inequality that connect speciesism and social injustice, structural and historical connections that bind inter-species channels of discrimination with mankind's own universe of intra-species disenfranchisement.10 If speciesism indicates a willingness to confer privilege on the basis of purported biological superiority, then that division may equally speak to, and be analogised with, a range of other distinctions wielded as justification for prejudice: ethnicity, gender and class, to name but the most commonly cited.

The experience of marginality and exclusion that occurs within racialised and gendered frameworks are often portrayed in the metaphorical language of animality, with depictions of oppression cast in the dehumanising light of subhuman treatment. Codes of domination that operate to uphold forms of social privilege are akin to the logic that undergirds the subjugation and abuse of nonhuman creatures; if identity politics are founded on the intersection of various axes, then species, as a category, may be utilised as a tool of discrimination against both animals and disadvantaged minorities.11 The notion of the total liberation framework recognises the interrelatedness of inequality across the span of our planet's life. It takes not just socio-cultural factors into account, but also the interests of nonhuman entities, enacting a critique of multifarious, complex matrices of domination, from racism to capitalism to speciesism. More to the point, total liberation, as David Pellow parses it, involves "socioecological inequality", the ways by which "humans, nonhumans, and ecosystems intersect to produce hierarchies — privileges and disadvantages — within and across species and space ... intertwined in the production of inequality and violence..."12 The discourse of animality, in other words, is bound up in the conjunction of strands of socioecological segregation, embedded in layers of oppression. The moral imperative of an ethics of the zoological that runs parallel to social equality may perhaps be summed up thusly: "As long as this humanist and speciesist structure of subjectivisation remains intact, and as long as it is institutionally taken for granted that it is all right to systematically exploit and kill nonhuman animals simply because of their species, then the humanist discourse of species will always be available for use by some humans against other humans."13

As the COVID-19 virus rampaged its way through Singapore in 2020, the alignment of inter- and intra-species ostracism became appreciable in the language that grew up around the migrant worker crisis, representing a confluence of socioecological marginalisation informed by speciesist assumption and race- and class-based discrimination.14 Daily reports of infection rates, put out by the Ministry of Health, uncoupled numbers of new COVID-19 cases into distinct categories: for "community" cases, i.e. the general population, and migrant workers, with the latter's exclusion from the collective body of the "community" all too conspicuous. Lawrence Wong, co‐chair of Singapore's Multi‐Ministry Taskforce set up to oversee contagion management measures, noted: "I think it is important to realise and recognise that we are dealing with two separate infections — there is one happening in the foreign worker dormitories, where the numbers are rising sharply, and there is another in the general population where the numbers are more stable for now."15 The government's model of pandemic management served to reinforce the existing divide between the country's citizenry and the foreign bodies in its midst, a reinforcement of the policy of social distancing in a wholly unintended manner. The reality of two pandemics in Singapore, encoded into official policy by the authorities, was rendered starkly apparent, as was the logic of exclusion that underlay this dynamic.

Denunciations of the treatment of these workers were vociferously aired in the media, along with a questioning of their long-standing exploitation. Tropes of animality and the nonhuman swiftly made their way into media reports. Numerous commentators highlighted the estrangement of migrant workers from Singaporean society at large, the radical curtailment of an already circumscribed range of liberties that they had enjoyed before the pandemic simply reinforcing their less-than-human status. Writing in Foreign Policy, political activist Kirsten Han titled her piece, "Singapore Is Trying to Forget Migrant Workers Are People."16 The sentiment was echoed by another prominent activist, Alex Au of the migrant rights group, Transient Workers Count Too, when he remarked: "Our government doesn't quite see them as fully human."17 As a response to the mandating by the authorities of a safe distance between passengers on the sort of open-deck lorries or pick-up trucks commonly used to ferry migrant labourers, a video began circulating with a proposal to install partitions on these vehicles. The proposal had the result of creating isolated cubicles, and comparisons to the treatment of animals were almost immediate. "[This is] showing people exactly what they think of foreign workers — animals", a Facebook user snapped, while another wrote: "The design (looks) like animal cages on displays..."18 The idea that this marginalised group was less than human was repeated by a migrant worker himself, an individual from Bangladesh named Sharif, who was quoted in a BBC piece as saying: "When I see a law only for migrant workers I think, 'Are we not human? Or are we animals? Do we not understand anything?"19

It was against the backdrop of the ongoing crisis that Zhao began working on the series, A Great Sign Appeared. In addition to those of openbill storks, other images featured swallows, long-tailed parakeets and flying foxes that were sighted in and around Singapore's urban areas. Tellingly, the conceptual underpinning of these works framed nonhuman animals as all too human subjects. The vernacular of animality and subhumanity so flagrant in public discussions of the migrant labourers' plight was reversed — nonhuman animals were anthropomorphised, the lingo of speciesism jettisoned for a language of equal consideration and, in the artist's own reckoning, neighbourliness.20 "Nonhuman species have always co-existed with human beings", he notes, "even in highly urbanised areas. During the Covid-19 health crisis, when travel was limited, I started to look more closely at my everyday surroundings and became more sensitive to the proximity of nonhuman neighbours in the middle of built-up Singapore."21 Long-tailed Parakeets, Vulnerable/Feral (2021), for one, sets a flock of the titular species (Psittacula longicauda) in a nocturnal milieu.22 The avian bodies are discernible in the dark only by their pale colouring, with the presence of a pair of apartment blocks indicating the setting of a public housing estate.

Photo credit: Long-tailed Parakeets, Vulnerable/Feral (2021), Robert Zhao. Image courtesy of the artist

The work, likewise a manipulated digital image, takes on a real-life avian spectacle that occurs daily in the Choa Chu Kang neighbourhood:

... I was also interested in a sense of everyday neighbourliness we had with nonhuman species. At 7 p.m. sharp every evening, a single tree in Choa Chu Kang HDB estate becomes alive with hundreds of long-tailed parakeets returning to their roost after a whole day of foraging. Nobody knows exactly why they are attracted to this tree and congregate there in such large numbers. The birds fly in big groups and chitter at a high volume, but the spectacle is over in less than 10 minutes as the parakeets settle in for the night.23

For Zhao, who resides in an adjacent housing estate, the locale of this daily ritual lent the term, 'neighbour', a literal significance. His description includes the specification of an exact time of day; the pinpointing of a particular abode, in the manner of an address; the conjuration of the routine of returning home after a day's labour; the suggestion of communication among the parakeets. The portrayal imbues its participants with, indeed, an almost neighbourly quality, suggesting the physical and ideological propinquity of these birds. The collapse of the distinction between animal and human ontologies here is salient. The gesture of reading the animal as human, of humanising birds as neighbours, assumes oppositional force in the face of a public debate that sought to portray the human as mere brute, disempowered individuals animalised and ostracised.24 The deliberate reversal of the human-animal hierarchy in his images may well be understood, then, as a retort to the animalian discourse that framed perceptions of the migrant worker community during the hysteria of the pandemic, a discourse that revealed the intersection of racist and classist assumptions with the prerogatives and prejudices of speciesist impulses.

The contiguity between humanised animals and animalised humans, linked through narratives of incursion that colour the perception of migrants, is also foregrounded in Zhao's more recent experiential work. Singapore Javan Mynah Society (2022) was included in an exhibition held at a retail space on Orchard Road, Singapore's main shopping enclave, and featured, as its chief component, guided walks to several Angsana trees (Pterocarpus indicus) in the vicinity. Large flocks of Javan mynahs (Acridotheres javanicus) would arrive every evening to roost in these trees — a spectacle not unlike that of the Choa Chu Kang parakeets.

Photo credit: A photographic memento from Singapore Javan Mynah Society (2022), Robert Zhao. The viewer’s image is digitally superimposed onto that of a flock of Javan mynahs along Orchard Road. Image courtesy of the artist.

The tale behind the tours concerned the titular organisation, a fictitious entity dreamt up by the artist:

Sundown at Orchard Road in Singapore is marked by a massive flurry of mynahs coming to roost. Over the years, business-owners have taken measures — including deploying a hawk to prey on the birds — against the mynah population, mostly in vain. In the 1980s, a group of local nature lovers formed the Singapore Javan Mynah Society, hoping to turn the roosting event into a tourist attraction. The society led tours out to Orchard Road to witness the roosting, which they marketed as "a spectacular natural phenomenon" in the heart of the city.25

While the Singapore Javan Mynah Society may be a fabrication, the problem of Orchard Road's roosting mynahs is an ongoing reality.26 Dramatically large flocks of the birds would descend at dusk on selected trees along the street, creating a ruckus and leaving behind a sea of excrement on the sidewalks. The species has been described as being "very vocal, forming huge communal roosts in trees", and its call comprised of "strident notes and whistles".27 On a walk led by Zhao in March 2022, the birds were witnessed in action first-hand by this author, and it was indeed a sight to behold: what seemed to be hundreds, if not thousands, of mynahs swooping into two particular trees as if by choreographed coordination, their numbers attested to by shrill, clamorous shrieks that coalesced into an obstreperous crescendo, drowning out almost all other ambient noise in the vicinity.

Video credit: Javan mynahs roosting along Orchard Road on March 3, 2022. Video shot by the author on an iPhone.

Once again, the undesirability of these pests was rendered in the language of anthropomorphism. A report noted of the mynahs' presence along a prime slice of real estate that, "these residents just refuse to be evicted", while another account remarked on the human-like dimension of their behaviour: "They call to each other when entering and leaving their roost — much as humans say hello and goodbye."28 They proved such a point of interest, in fact, that a short documentary film, Man vs Birds, was produced on the topic.29 The filmmakers interviewed various individuals, including the director of the Orchard Road Business Association, who pointedly observed of the feathered denizens: "Every evening, between 6.30 and 8 o'clock, they actually come down this way to Orchard Road — and they come here to have dinner and chit-chat." The anthropomorphic depiction of these birds recalls Zhao's characterisation of the long-tailed parakeets — but what is of especial interest in this case is the narrative of invasion. The native range of the Javan mynah originally encompassed the islands of Java and Bali in the Indonesian archipelago. It was introduced to Singapore in the early 1900s, eventually becoming so successful in its adopted home that it outnumbers endemic mynah breeds today.30 Invoking the image of trespassing hordes, the film claimed that, on a daily basis, "nearly three thousand litres of high-pressured water are commandeered to scrub away evidence of avian incursion", a reference, of course, to the birds' waste. The idea of incursion was reiterated in a letter published in The Straits Times, Singapore's main daily, the author of which cast the issue in binary terms of overwhelming foreigners and overrun locals: "The International Union for Conservation of Nature has declared the mynah one of the world's most invasive species ... While we welcome nature and small animals in our habitat, the rampant growth of the mynah population has led to a co-existence that is too close and raucous for comfort."31

The spurning of any possible co-existence reflected the perceived threat to native ecosystems, and the implied comparison to human cross-border movement only too apparent; that Javan mynahs are considered an invasive species fed into broader, extant conversations about indigeneity and, by extension, immigration.32 The issue of avian incursion and excrement in Man vs Birds served to evoke the common perception of poor immigrants as dirty, unhygienic individuals, as the letter in the Lianhe Zaobao Forum page insisted of migrant workers. Elsewhere, protests by the residents of a neighbourhood where a workers' dormitory was to built were likewise premised on "fears that the low-skilled foreigners will soil their parks, clog up their streets as well as violate their children and womenfolk."33 Anxieties over numerical and ecological superiority in the Straits Times letter simply reinforced tropes of foreign domination through sheer numbers. These tropes are often expressed in the use of disaster-related terms such as deluge and flood — e.g. "a flood of foreigners" — and in a manner that dilutes "aggregate individuals into an undifferentiated mass quantity" ... [and] effaces their humanity", singular subjectivity lost to view amidst fear of the crowd.34 The enlacing of speciesist instinct and anti-immigrant sentiment is manifest in the conflation of an invasion of avian annoyances and an influx of foreign labour. The lines drawn between native and alien, whether mynah or worker, are bound up in an economy of socioecological inequality that analogises the humanised animal and the animalised human, based as much on socio-political structures as on metaphorical cogency. Speciesism, after all, not only denotes"a logical or linguistic structure that marginalizes and objectifies ... but also a whole network of material practices that reproduce that logic as a materialized institution and rely on it for legitimation."35 These institutional practices, apropos of Singapore's migrant worker community, involve acts of silencing — acts mirrored in the visual silence of Robert Zhao's images.

Silence

As Zhao noted, numerous exercises were undertaken over the years by the authorities to discourage the Orchard Road mynahs from their nightly mass appearance, attempts that clearly failed to achieve the desired results. In 2009, several malls on the Orchard strip utilised sonic devices to scare the mynahs away, while elsewhere on the island, where the birds proved themselves an equal nuisance, the Agri-Food and Veterinary Authority experimented with aiming laser beams at gathering flocks to deter them.36 Other methods included pruning their trees of choice, applying spicy gel to the branches, and the use of large net traps to capture the mynahs, after which they were "humanely euthanised" with carbon dioxide.37 One particularly noteworthy method was the employment of the services of a predator — namely, a hawk. The accipitrine and its handler were loaned from the Jurong Bird Park but, as matters transpired, the bird of prey proved to be too intimidated by the overwhelming numbers of its ersatz prey.38

The attempts to literally silence a supposedly invasive, non-indigenous species is representative of the state's efforts in regulating and muzzling the voices of other non-indigenous communities. If the imperatives of capitalist dominance that underlies speciesism may be understood as an analogue for channels of profit-driven, socialised control, then the attempts to mute the mynahs of Orchard Road may be read alongside other forms of enforced inarticulacy, an intersection of the physiological and socio-political. For the typical migrant labourer in Singapore, imbricated in the reality of their powerlessness is the condition of their silence, enforced through means political, cultural and bureaucratic.39 The precarity of their presence in the highly regulated island-state is assured by their exclusion from the nucleus of rights afforded to citizens. As a conceptual lens though which to view labour conditions, the idea of precarity is understood to refer to work marked by uncertainty, instability and high risk. The so-dubbed global "precariat" is theorised to be a class of workers subject to forms of labour-related insecurity, doing without income security (assurance of an adequate stable income) and employment security (protection against arbitrary dismissal), among others.40 Generally understood to be a symptom of neo-liberal capitalism, low-skilled, low-wage — and sometimes illegal — migrant workers are especially ripe to be exploited and abused, their "lack of access to collective organisation, social protection and citizenship entitlements ... seen as desirable qualities that make them particularly susceptible to insecure and potentially exploitative employment conditions."41

At the level of the everyday, migrant workers in Singapore are subject to draconian employment requirements intended to circumscribe their social participation and economic autonomy, institutionalising the conditions of precarity and silence. Indigent migrant workers often incur substantial debt — involving payments to an intermediary such as an employment agency — to secure a visa, and be able to travel to Singapore to take up employment. This financial indebtedness already ensures a "compliant, diligent and stable worker" at the outset.42 In Singapore, the bureaucracy of the employer-sponsored work permit system allows for an inordinate amount of control over foreign hires. For one, employees may only switch employers with consent, which may be denied without reason. Employers are, under the law, also empowered to unilaterally cancel work permits, the result of which is repatriation to the individual's home country. This state of affairs, quite naturally, feeds into an asymmetrical dynamic where employers wield unchecked power against their foreign workers, with employees fearful of repatriation — often for no stated reason — maintaining silence in the face of labour abuses; as various accounts have indicated, there have also been cases of employers cancelling work permits to avoid paying salaries, or using the threat of so doing as leverage against possible complaints to the authorities.43 To that end, a survey conducted in 2013 by researchers at the Singapore Management University reported that some 65% of work permit holders with salary or medical claims workers surveyed reported having been threatened by their employers with premature repatriation.44

Foreigners in Singapore are, of course, also shut out from the political processes and decisions that directly affect them; their speech is, consequently, untethered from any means of political agency. For many migrant workers, this political impotence is embodied in a host of regulations that not only deny them due protections in the labour market, but also individual liberties that a citizen would take for granted. Holders of work permits may only reside at an address specified by the employer; they may not marry a Singapore citizen or permanent resident without official approval; women should not get pregnant or deliver a child in Singapore (unless already married to a Singapore citizen or permanent resident).45 This radical circumscribing of personal freedoms is further amplified by cultural and linguistic barriers that compound the want of knowledge about Singapore's legal system and administration, simply constituting yet another channel through which silence is ensured. The Singapore government, ultimately, demands compliance through the absolute ability to expel undesirable foreign elements. It "justifies the right to expel workers as part of its sovereign power ... one of the conditions under which foreign nationals are allowed the privilege to come here to work is that they can be repatriated if, for example, the Minister assesses them to be security threats."46 The net effect of this, of course, is both actual and rhetorical silence, socio-political precarity registered as the absence of speech, and muteness signifying a foreclosure of agency.

The voicelessness of the migrant worker dovetails with modes of silence operative in Zhao's work. Salient in the manipulated tableaux of the Great Sign series is a curious fact: the optical illegibility of his avian subjects, compositionally obscured and visually precarious. These images extend the documentary language of the camera to the very edge of the cognisable, where the feathered creatures teeter on the brink of anonymity, non-spectacles evading the grasp of the gaze.47 And A Great Sign Appeared (Thailand-Singapore) pictures the flock of openbill storks as a premonitory phenomenon in the sky, their collective appearance resembling the eponymous harbinge, while Long-tailed Parakeets, Vulnerable/Feral shifts the otherwise crepuscular roosting habits of the parakeets into the dark of night, their slight forms seemingly only decipherable by lights emanating from apartment windows nearby. Other images in the series likewise reduce the visual accessibility of their subjects. And A Great Sign Appeared (Things from the Heat) captures a separate sighting of the storks, relegating them to a mass of minute, barely discernible shapes hovering around what looks to be a transmission tower, their presence and significance dwarfed by the comparatively more monumental scale of other elements in the scene: a tower, trees, apartment blocks and vehicles.

Photo credit: And A Great Sign Appeared (Things from the Heat) (2021), Robert Zhao. Image courtesy of the artist.

Swallows, Arrived tells the tale of migratory swallows which, between October and February, roost in apartment blocks in certain areas of Singapore. Zhao writes that, "It is not known why these swallows would choose only certain apartment blocks. Experts believe that this could be due to the urban heat effect, where the warmer, built-up areas provide these small birds with their preferred environment for roosting."48 Paralleling the absence of certainty about the avian motives is the lack of visual clarity. The image borders on the almost completely abstract, the bodies of the birds reduced to little more than a field of diminutive specks set against a nocturnal sky, with the tops of the rectilinear outlines of buildings just perceptible in the gloom.

Photo credit: Swallows, Arrived (2021), Robert Zhao. Image courtesy of the artist.

In a series of images centered on birds, the avian subjects are decentered, poorly glimpsed enigmas. The vocabulary of ocular interference in these works, a visuality that actively eludes the scopophilic impulse — or what Laura Mulvey referred to, via Freud, as the "controlling and curious gaze"49 — manifests a deep-seated unease with the demands of vision. Elsewhere, I have written of the non-affirmative character of images that rebuff the viewer's scrutiny, that refuse to affirm the desires of scopophilia, as an alignment with the configurations and connotations of the poor image.50 According to Hito Steyerl, the poor image is "a ghost of an image, a preview, a thumbnail, an errant idea, an itinerant image ... ranked and valued according to its resolution."51 It is lo-res and lo-def, pixelated and out-of-focus. It is blurred and indistinct through copies and downloads, its illegibility consistently inscribed onto multiple iterations. Steyerl adduces the example of a character in Woody Allen's film, Deconstructing Harry, who is played by Robin Williams: "... the main character is out of focus. It's not a technical problem but some sort of disease that has befallen him: his image is consistently blurred ... His lack of definition turns into a material problem. Focus is identified as a class position, a position of ease and privilege, while being out of focus lowers one's value as an image." The class position of focus, and, by extension, clarity, definition and resolution, feeds into the political economy in which poor images and their modes of dissemination play a part. The pictorial inadequacy of these images must be measured against the "classical public sphere mediated and supported by the frame of the nation state or corporation." Against, in other words, the rich image, found on theatre screens, HDTV, magazines and other authorised media — pictures possessed of the requisite sharpness and clarity. The poor image not only resists the resolution fetish of its orthodox counterpart, it likewise gainsays big business and the state apparatus.52

Steyerl's use of economic metaphors is telling. In the foreground, once more, are issues of class differentiation. As she points out, "Poor images are poor because they are not assigned any value within the class society of images ... Their lack of resolution attests to their appropriation and displacement." While Zhao's photographs may hardly be thought of as poor of resolution or definition, his deliberately cryptic, frustratingly elusive avian forms certainly seem redolent of Robin Williams's character, at once out of focus optically and socially. The implications of socio-economic class in his work may perhaps best be understood by reading the circumvention of the desires of the gaze as a mode of visual silence, a scopophobia that is simultaneously a synaesthetic analogy for muteness — with the absence of the voice, an expression of individual subjectivity, serving as a signifier of the loss of agency. Both bird and man play, ultimately, the role of the subaltern in broader social networks. Human and nonhuman actors are linked in the alterity of their respective positions in the socioecological field, assuming the position of the Other to those for whom the boon of citizenship and species confers the privilege of subjecthood. The intersection of intra- and inter-species discrimination may be extended to one particular aspect of the theoretical formulation of the subaltern, who is caught in disparities of power, his subordination constituting one term in a binary relationship of which the other is hegemony.53 The distinguishing characteristic of the subordinate class is, fundamentally, its exclusion from the mechanisms of dominance. Gayatri Spivak has observed that the work of subaltern studies project is "a task of"measuring silences", of what a text cannot or refuses to say.54 The subaltern consciousness remains in many ways elusive to the praxis of history, or to its elite makers and writers, which, despite its attempted recuperation,"is never fully recoverable, ... is always askew from its received signifiers, indeed ... is effaced even as it is disclosed."55 It is those signifying silences, always already hidden from privilege, that intervene between the commentator and the subaltern subject; access is finally mediated through"elite documentation that give us the news of the consciousness of the subaltern."56

The silence of the subaltern, then, inheres in Zhao's images. His digitally altered photographs of barely recognisable, indistinguishable birds and their numerous, anonymous, repetitive forms, bordering on the microscopic, deny the viewer's agency. The correspondence here is between the rhetorical silence of the migrant worker and the visual antipathy of his feathered creatures, one that transposes the muteness of the first into the lack of clarity in the second. If vision aspires to lucidity — if seeing connotes the desire to see unimpeded and unproblematically — then the optical inaccessibility of the supposed objects of interest in these works finds a correspondence in the structural dichotomy that frames the existence of the subaltern. Subalternity as a theory wherein the agential impulse develops in a bottom-up trajectory yet remains displaced from the consciousness of the privileged classes, is signalled by these visual texts. The obscurity of the birds suggests an effective obstruction of the gaze, the loss of visual legibility redolent of the occluded consciousness, and the silence, of the subaltern, removed from systems of privilege. The poor image, in Zhao's hands, functions as an analogue of the figure of the migrant labourer — the poor image that is unallied with those mechanisms of power that maintain the scopic regime consumed by the public, a regime premised on the sharpness and definition devised by capitalist resources and hegemonic political power.57 The migrant worker in Singapore is alienated, disenfranchised and silenced, a non-citizen and non-subject distanced from and understood poorly by the populace at large. What is poorly visible, in this case, becomes symptomatic of what is ill-understood.

The contiguity between human and nonhuman animals in twenty-first century Singapore may be located in the analogic space that subsists between the silence of the subaltern, and the scopophobia of Zhao's work. While the sciences have been primarily responsible for the provision of a naturalised source of empirical knowledge, justifying the dominion of man over his animal counterpart with the language of biological superiority, those power relations, where evolutionary might is right, are expressed in daily life in explicitly political and socio-cultural ways. The encounters behind his Great Sign series are rhetorically framed in all-too-human terms, describing his avian subjects as neighbours yet simultaneously erasing identifiers of these feathered creatures. They oscillate between proximity and anonymity, subjecthood and scopophobia, speaking evocatively and obliquely to the precarious figure of the migrant labourer in twenty-first century Singapore. At a juncture when the island-state has been experiencing a fierce public debate on its treatment of migrant workers, as well as the role of continued immigration in its future, the otherwise parallel strands of subalternity — economically instrumentalised and socially marginalised human labour, and disposable, invisible nonhuman migrants — find a point of intersection in situating Zhao's avian engagements within their specific socio-historical moment, a socioecological nexus of class, race and speciesism marked by the language of metaphorical echoes, and silence.

The author thanks Robert Zhao, the organisers of the Julius Baer Next Generation Art Prize and the Silvana S. Foundation Commission Award Exhibition, and Juria Toramae.

Footnotes

- Unless otherwise stated, all works in the series, And A Great Sign Appeared, are dated 2021. Zhao was the recipient of the inaugural Silvana S. Foundation Commission Award in 2020, which commissioned the series. The works were featured in the 2022 exhibition, Rediscovering Lost Connections: Silvana S. Foundation Commission Award First Edition. The individual piece, And A Great Sign Appeared (Thailand-Singapore), was also the second prize winner in the Still Image category of the Julius Baer Next Generation Art Prize in 2021, and was featured in its virtual reality exhibition of finalist works. The author was the curator of both exhibitions. ↩

- Audrey Tan, "Hundreds of Asian openbill storks spotted in Singapore", The Straits Times online, 8 December, 2019. Retrieved from https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/environment/hundreds-of-asian-openbill-storks-in-singapore-in-rare-sighting-with-possible. Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- According to the relevant page on the website of the Institute of Critical Zoologists (ICZ), "And A Great Sign Appeared". The ICZ is a fictional construct that serves as an ongoing umbrella project for Zhao, under which individual works and series are subsumed. Retrieved from . Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- A note on foreign labour in Singapore: the city-state's economy is reliant on a substantial foreign labour force, which, in 2021, counted for some 1.2 million individuals out of a total population of almost 5.5 million. Imported labour is differentiated between skilled, mostly white-collar migrants, referred to by the complimentary sobriquet "foreign talent", while low-skilled, low-wage labourers are deemed "migrant workers". The latter category is comprised largely of employees in the so-called CMP (construction, marine shipyard and process) industries and MDWs (migrant domestic workers) — terms utilised by the relevant authorities. Policies and regulations impacting these different groups vary vastly, with migrant workers afforded few liberties and protections. Studies of class-based divisions in Singapore's foreign labour may be found in Junjia Ye, Class Inequality in the Global City: Migrants, Workers and Cosmopolitanism in Singapore (London and New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2016), and Brenda S. A. Yeoh, "Bifurcated labour: The unequal incorporation of transmigrants in Singapore", Tijdschrift voor Economische en Sociale Geografie, vol. 97, issue 1 (2006): 26-37. For the latest statistics, refer to the relevant page on the Ministry of Manpower's website at https://www.mom.gov.sg/documents-and-publications/foreign-workforce-numbers. Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- Justin Ong, "How S'pore tamed a Covid-19 outbreak at workers' dorms, avoiding a 'major disaster", The Straits Times online, 22 January 2022. Retrieved from https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/how-spore-tamed-a-covid-19-outbreak-at-workers-dorms-avoiding-a-major-disaster. Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- Shibani Mahtani, "Singapore lost control of its Coronavirus outbreak, and migrant workers are the victims", The Washington Post online, 21 April 2020. Retrieved from . Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- The text of the letter, translated from the original Chinese, is reproduced in Joshua Lee, "Covid-19 outbreak in dorms due to migrant workers' poor hygiene and bad habits: Zaobao forum letter", Mothership, April 15, 2020. Retrieved from https://mothership.sg/2020/04/migrant-workers-zaobao-letter/. Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- Peter Singer, Animal Liberation (New York: Ecco, 2002), p. 6. Singer's tome, first published in 1975, is now considered a foundational text in the animal rights movement, credited with popularising the use of "speciesism", though the term was coined by activist Richard Ryder in the early 1970s. ↩

- Ibid., 9. ↩

- The roots of speciesism as a concept resonates with the aims of intersectional theory, which examines the ways in which markers such as gender, race and class are imbricated in the construction of identity and alterity. For overviews of these ideas, and the scholarship that has contributed to the understanding of animals rights and intersectionality, see Anthony J. Nocella et al, "Introduction: The Emergence of Critical Animal Studies: The Rise of lntersectional Animal Liberation", in Defining Critical Animal Studies: An lntersectional Social Justice Approach for Liberation, eds. Anthony J. Nocella et al (New York: Peter Lang, 2014), pp. xix-xxxvi, and Maneesha Deckha, "Animal Advocacy, Feminism and Intersectionality", DEP, vol. 23 (July 2013): 48-65. ↩

- The label, "animal", in fact, was indicted as an uncritical generality by Jacques Derrida, who remarked: "... as if all nonhuman living things could be grouped without the common sense of this "commonplace,"the Animal, whatever the abyssal differences and structural limits that separate, in the very essence of their being, all"animals,"..." Jacques Derrida, trans. David Wills, "The Animal That Therefore I Am (More to Follow)", Critical Inquiry, vol. 28, issue 2 (Winter 2002): 369-418. See p. 402. ↩

- David Naguib Pellow, Total Liberation: The Power and Promise of Animal Rights and the Radical Earth Movement (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2014), p. 7. ↩

- Cary Wolfe, Animal Rites: American Culture, the Discourse of Species, and Posthumanist Theory (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), p. 8. ↩

- Language politics confronting Singapore's migrant worker community are examined in Rani Rubdy and Sandra Lee McKay, ""Foreign workers" in Singapore: conflicting discourses, language politics and the negotiation of immigrant identities", International Journal of the Sociology of Language, vol. 2013, issue 222 (2013): 157-185. ↩

- Qtd. in Satveer Kaur-Gill, "The COVID-19 Pandemic and Outbreak Inequality: Mainstream Reporting of Singapore's Migrant Workers in the Margins," Frontiers in Communication, vol. 5, article 65 (September 2020), unpaginated. Retrieved from https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcomm.2020.00065/full. Last accessed August 4, 2022. For a further look at how the pandemic impacted migrant workers in Singapore, see Mohan Jyoti Dutta, "Singapore's Extreme Neoliberalism and the COVID Outbreak: Culturally Centering Voices of Low-Wage Migrant Workers", American Behavioral Scientist, vol. 65, issue 10 (September 2021): 1302-1322. ↩

- Kirsten Han, "Singapore Is Trying to Forget Migrant Workers Are People", Foreign Policy, 6 May 2020. Retrieved from . Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- France 24, "'Like prison': Singapore migrant workers suffer under Covid curbs", 13 November 2021. Retrieved from . Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- Qtd. in Ewe Koh, "Singaporeans Are Divided Over a Company's Plan to Transport Migrant Workers in Lorries That Look Like 'Animal Cages", Vice, 15 May 2020 Retrieved from . Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- Qtd. in Nick Marsh, "Singapore migrant workers are still living in Covid lockdown", BBC News, 24 September 2021. Retrieved from . Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- Various animal theorists have noted the dangers of the anthropomorphic bent in discussing animalian subjectivity. Both sides of the argument are laid out succinctly in Derek Ryan's Animal Theory: A Critical Introduction (Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, 2015), pp. 36-41. ↩

- ICZ, "And A Great Sign Appeared". Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- It should be noted that the long-tailed parakeet is a species endemic to the Malay peninsula and Singapore, rather than a migratory one. ↩

- ICZ, "And A Great Sign Appeared". Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- As Cary Wolfe has pointed out, cross-species analogies between human and nonhuman are ordered on a scale: animalised animals occupy the lowest rung of the ladder, used and abused by the animal industrial complex; humanised animals include pets, the ostensibly human-like characteristics of which spare them the fate of the previous group; animalised humans are the victims of socio-cultural rubrics that legitimise subordination and violence by their fellow man; finally, the humanised human reigns "sovereign and untroubled" atop this system. See Wolfe, p. 101. ↩

- ICZ, "Singapore Javan Mynah Society." Retrieved from https://criticalzoologists.org/javanmynah/index.html. Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- On the use of fictional narratives in Zhao's practice, see Yeo Wei Wei, "Zhao Renhui's Frame of Fiction", Reflect / Refract, 01 (2013): 21-32. ↩

- Allen Jeyarajasingam, A Field Guide to the Birds of Peninsular Malaysia and Singapore, 2nd ed. (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 2012), p. 333. ↩

- The first quote is from David Ee, "Orchard Road: Less of a bird street?", The Straits Times, 15 October 2012, p. A3. The second is from Lee Jin Hee, "Javan Mynahs, 'Invasive Species' and Belonging in Singapore", Eating Chilli Crab in the Anthropocene, ed. Matthew Schneider-Mayerson (Singapore: Ethos Books, 2020), pp. 139-57; see p. 140. ↩

- Man vs Birds (2015), directed by Kylie Tan and Priscilla Goh, was produced as part of Discovery's SG50 Singapore Stories series. All quotes from the film refer here. It is available for viewing at . Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- Jeyarajasingam, p. 333. ↩

- Neo Lin Chen, "Control mynah population too", The Straits Times online, November 16, 2015. Retrieved from https://www.straitstimes.com/forum/letters-on-the-web/control-mynah-population-too. Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- Yasmin Y. Ortiga, "Multiculturalism on Its Head: Unexpected Boundaries and New Migration in Singapore", Journal of International Migration and Integration, vol. 16, issue 4 (November 2015): 947-63, is a useful summation of the recent immigration debate in Singapore, as well as related questions that arose concerning the country's much vaunted but increasingly frayed multicultural ethos. ↩

- Qtd. in Rubdy and McKay, p. 165. ↩

- Ibid. ↩

- Wolfe, p. 101. ↩

- Cynthia Choo, "'Cacophony' of mynah birds a headache for some Potong Pasir residents", Today, 9 August, 2018. Retrieved from . Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- Lee, "Javan Mynahs", p. 139. ↩

- Jessica Lim, "Hawk no match for pesky mynahs", The Straits Times, October 14, 2012, p. 8. ↩

- It is worth noting that, on a symbolic register, the rhetorical silence of the South Asian migrant labour community in Singapore was disrupted in an unprecedented way on December 8, 2013, when a riot broke out in the Little India district. A scaffolding company employee from India, Sakthivel Kumaravelu, was involved in a fatal bus accident in the neighbourhood, which resulted in an angry mob of South Asian migrants turning on first responders and security forces. It was, as numerous reports pointed out, the first instance of a riot in the tightly policed island-state in more than four decades. For reflections on the event in the context of Singapore's climate of discrimination, see Jaclyn L. Neo, "Riots and Rights: Law and Exclusion in Singapore's Migrant Worker Regime", Asian Journal of Law and Society, vol. 2, issue 1 (May 2015): 137-168, and Satveer Kaur et al, "Media, Migration and Politics: The Coverage of the Little India Riot in The Straits Times in Singapore", Journal of Creative Communications, vol. 11, issue 1 (March 2016): 27-43. ↩

- As defined in Guy Standing, The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class (London and New York: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011), p. 10. ↩

- Grace Baey and Brenda S. A. Yeoh, "'The lottery of my life':Migration trajectories and the production of precarity among Bangladeshi migrant workers in Singapore's construction industry", Asian and Pacific Migration Journal, vol.27, issue 3 (September 2018): 249-272. See p. 253. ↩

- Geerhardt Kornatowksi, "Caught up in policy gaps: distressed communities of South-Asian migrant workers in Little India, Singapore", Community Development Journal, vol. 52, issue 1 (January 2017): 92-106. See p. 97. ↩

- For specific case studies in which Singaporean employers of migrant workers have abused the system, refer to Baey and Yeoh, as well as Sallie Yea and Stephanie Chok, "Unfreedom Unbound: Developing a Cumulative Approach to Understanding Unfree Labour in Singapore", Work, Employment and Society, vol. 32, issue 5 (October 2018): 925-941. ↩

- Neo, "Riots and Rights", p. 143. ↩

- Regulations relevant to work permit holders are found on the website of the Ministry of Manpower, at https://www.mom.gov.sg/passes-and-permits/work-permit-for-foreign-worker/sector-specific-rules/work-permit-conditions. Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- Neo, "Riots and Rights", p. 148. ↩

- While the obscured subject is often witnessed — or unwitnessed, as it were — in Zhao's images, he has also utilised the close-up as a visual tactic, in works such as Sleeping Mata Puteh #2 (Winner of the Last Bird Song Competition to be Held at 'Red House' Tiong Bahru in 2005) (2012) and A Guide to the Flora and Fauna of the World (2013). ↩

- ICZ, "And A Great Sign Appeared", at: criticalzoologists.org/greatsign/index.html. ↩

- Laura Mulvey, "Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema", Screen, vol. 16, issue 3, Autumn 1975, pp. 6-18. See p. 9. ↩

- In the context of the photographic work of another Singaporean artist, Jason Wee; see Louis Ho, "The Non-Affirmative: Jason Wee, Photography, Scopophobia", Reflect / Refract, 01 (2013): 87-106. ↩

- Hito Steyerl, "In Defense of the Poor Image", e-flux Journal, issue 10 (November 2009), unpaginated. Retrieved from . Last accessed August 4, 2022. ↩

- See Ho, p. 91. ↩

- On the dangers of ascribing subaltern silence to the nonhuman animal and the seeming corrective of human language, see Kari Weil, Thinking Animals: Why Animal Studies Now? (New York and Chichester: Columbia University Press, 2012), pp. 5-7. ↩

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, "Can the Subaltern Speak?", Marxism and the Interpretation of Culture, edited by Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988), pp. 271-313. See p. 286. ↩

- Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, "Subaltern Studies: Deconstructing Historiography", Selected Subaltern Studies, edited by Ranajit Guha and Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1988), pp. 3-32. See p. 11. ↩

- Ibid, 12. ↩

- Film theorist Christian Metz coined the term "scopic regime" in "The Imaginary Signifier", Screen, vol. 16, issue 2 (July 1975): 14-76, as an explication of the differences between cinema and live theatre. Martin Jay would later utilise the idea of scopic regimes, as visual subcultures with "multiple implications of sight", in his essay "Scopic Regimes of Modernity" in Vision and Visuality, ed. Hal Foster (Seattle: Bay Press, 1988), pp. 4-27. ↩