Dissonant Creatures: Birds, Language and Theatricality in Jannis Kounellis's 'Poor Art' practice

by Elyssia Bugg

- View Elyssia Bugg's Biography

Elyssia Bugg is a writer and PhD candidate at the University of Melbourne researching performance practices in the Arte Povera movement.

Dissonant Creatures: Birds, Language and Theatricality in Jannis Kounellis's 'Poor Art' practice

ELYSSIA BUGG

"I desperately seek unity, albeit difficult to attain, albeit Utopian, albeit impossible and therefore dramatic."

- Jannis Kounellis, 1982 (32)

"Kounellis: Hey! What's going on? Hey! (to the parrot)"

- Jannis Kounellis, 1967 (12)

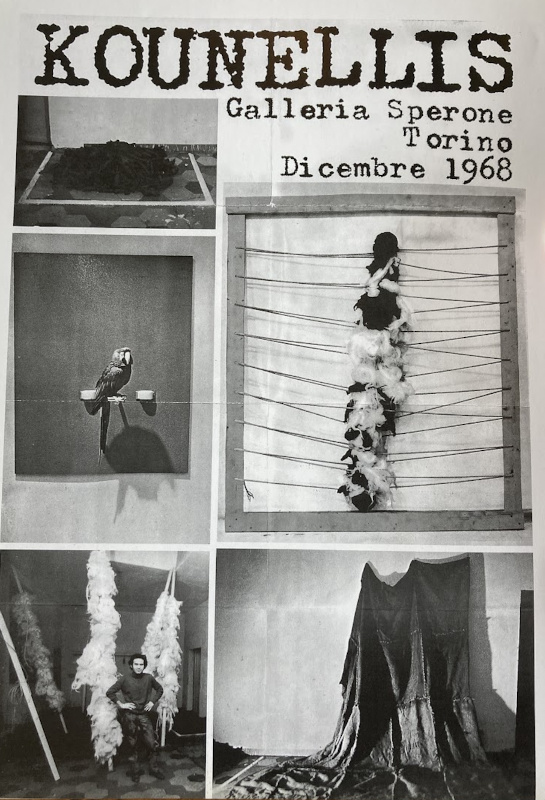

Photo credit: Kounellis Sperone Gallery Flyer 1968 - from: Gian Enzo Sperone. Turin Rome New York. 35 years of exhibitions between Europe and America

The catalogue essay for the 1967 exhibition Kounellis, held at Galleria L'Attico in Rome, is a script. The dialogue documents a conversation that took place in the gallery space in front of one of the titular artist's works. From the text the reader can gather that at least four children, the artist, and a parrot are in discussion, and together they speak to their surroundings — What colour is this? What's this thing? There are no profound statements trying to grasp at overarching themes, just observations about specific material details and the physical space they are occupying.

Of those in conversation, the parrot is the only one constituting a formal component of the artwork. The installation features four rows of cacti planted in an iron garden bed, a large steel prism bursting at the seams with white cotton, and a panel of wall-mounted metal with a perch, on which the live parrot stands. Though the parrot is "on stage" (Bätzner, Kounellis 422) while the rest of the participants in the script act as observers, the format of the catalogue text suggests that there is a particular kind of mutability being established between the work, its audience and the space.

This play — of structure and variability, spectator and spectacle, language and materiality — is typical of Jannis Kounellis's practice. There is a sense in his work that the combination of seemingly disparate factors is a way of resisting disjuncture, rather than fostering it. In particular, a desire for unity between the artistic, and the real and concrete, comes across, such as in the plain-speaking conversation in the catalogue text. As Ara Merjian writes, "despite their physical confinement to gallery spaces, Kounellis's works remain redolent of a world outside those walls". In this essay I will argue that Kounellis achieves this in many of his pieces through the composition of theatrical scenarios that are immersive in a manner that doesn't implicate the viewer in the work, so much as envelop the work in the context of the wider world.

Significantly, with regard to the theme of Birds and Language, it is the sensual components of these works, and in particular the incorporation of dynamic factors such as live animals, that is key to Kounellis's practice. Reviewing Kounellis's 2015 show at Galleria Christian Stein, Paolo Nicolin writes, "his work always suggests a register beyond the range of the visual. Indeed, the dense industrial materials, earthen hues, and odors that are typical of Kounellis's art elicit in me a magical synesthetic response; a textured noise accompanies my direct experience of the work." With this 'register beyond the range of the visual' in mind, I will analyse the way in which select works by Kounellis from the late 1960s access this holistic sense of worldliness. Specifically, I will take works in which he situated live birds within his compositions as exemplary of both the artist's theatrical sensibility, and his interpretation of the concept of Arte Povera (Poor Art) that his work came to be aligned with.

Kounellis was born in Piraeus, Greece in 1936. In 1956, he moved to Rome, Italy, where he would advance an artistic practice that qualitatively bridged theatre, performance, sculpture and installation art, but which (as I will discuss throughout this article) the artist self-definitively situated in the medium of painting. In his 1967 manifesto for Arte Povera, Germano Celant described Kounellis's particular contribution to the movement thus;

...struck by the richness of his existence, [Kounellis] recuperates artistic gesture in feeding bird food to birds, in detaching roses from a painting, and he loves to surround himself with banal but natural objects like coal, cotton, or a parrot. Everything is reduced to a concrete knowledge that struggles against all conceptual reductions of itself...

This concreteness was applied by Kounellis across mediums. In addition to his own practice, Kounellis collaborated on a number of theatrical productions. Describing this aspect of his work in a 1996 essay, he writes, "I have worked as a theatre person, with Carlo Quartucci or Heiner Müller, in new and classical spaces such as the Gobetti Theater or the Deutsche Theatre, or at the Opera in Amsterdam or in Berlin, but with liberties unknown to a set designer" (101—102). The concrete application of these liberties is evidenced by a 1968 performance titled I Testimoni (The Witnesses), that Kounellis collaborated on with director Carlo Quartucci. The set for this work consisted of a great many live birds. Nike Bätzner writes in the essay Jannis Kounellis: Action as Vibrant, Fulfilled Duration, "On the back wall of I Testimoni's set...there were 110 bird cages with finches in them. It is hard to even imagine the noise made by so many birds, plus the intermittent cries of a toucan in yet another cage" (147). As Nicolin does when reflecting on the 2015 show, the aspect of this work that Bätzner identifies as striking is the noise, a factor she links to Kounellis's desire to work "'with' the theatre" to develop a "critical presence" (ibid). In this way, we can see the likes of this avian cacophony, birds in general, and the particular theatricality with which they are deployed in Kounellis's practice, as making for an artistic strategy that fosters 'presence'. This 'critical presence', in the context of Kounellis's work, and the Arte Povera movement it assisted in shaping, is ultimately enacted through processes that ground art objects and art making within the plane of everyday experience.

From early in his practice, Kounellis's compositions demonstrated both a tendency toward the theatrical and a specific kind of materiality. In performance pieces reminiscent of Dadaism, Kounellis staged activations of works on canvas that saw language and text rendered material. For example, Giovanni Lista writes of a 1960 activation of Kounellis's Alfabeti (Alphabet) series wherein Kounellis, "wearing a toga and a paper mitre" performed chants using the numbers and letters stencilled on the canvasses (11). This signifies a particular synthesis of theatricality and painting that Kounellis would adapt and elaborate on over the course of his career. It was a practice developed as a conscious response to the work of artists like Alberto Burri, whose gestural incorporation of burlap sacks and industrial materials within the visual field of the canvas is repeatedly cited by Kounellis as an inspiration for his own work. Speaking to Willoughby Sharp for Avalanche Magazine in 1972, Kounellis provides an example of how he actioned this influence in his pre-Arte Povera era pieces:

In 1960...I did a continuous performance, first in my studio and then at the Galleria Tartaruga in Rome, in which I stripped unmounted canvases coated with Kemtone, an industrial housepaint, all over the walls in the room, and then painted letters on them which I sang. The problem in those days was to establish a new kind of painting — something to follow the Informal Art period (143).

We can see the impact this influence had formally in terms of the kinds of materials and processes the artist would engage. But additionally, this description provides evidence of the conceptual impact these earlier artists and movements had in terms of the way Kounellis conceived of his practice as operating within the medium of painting. This is notable because, at a glance, his installations, in their combination of ready-made items, live components and sculptural features, would appear to be more akin to an extension of theatre than painting.

Kounellis addresses this assumption directly in a 1968 interview for Marcatré Magazine, stating;

My work is absolutely the opposite of sets for the stage. It's like the difference between natural and naturalistic. Burri is natural, Tàpies is naturalistic. He rebuilds a wall, for instance, and therefore is scenographic. (130)

This is a useful insight, in that it identifies the function of the theatrical in Kounellis's work and goes some way to explaining the resonance his practice has with Arte Povera's conceptual project. In terms of the former, we can take from this interview that Kounellis did not, in 1968, see his compositions as merely suggestive. This theoretical position is perhaps self-evidently manifest in a work such as the 1967 installation at L'Attico, where the parrot, presented as active participant, defies those modes of interpretation that would seek to read it as either sign or signified. Rather than being gestural in the sense of generating an index for the act of creation, Kounellis's works appear to contain within them an element of involvement that is much more live and present. As such they are closer to, as he says, the natural rather than the naturalistic, in that his works are, at least in part, comprised of that which they also depict.

The use of text in this regard is worth noting, as it would in some ways seem contrary to Kounellis's experimentation with the conflation of the actual into the act and exhibition of painting. Text, and language, as referential systems could on one level be seen to create remove that connotes rather than truly captures its subject matter. However, Kounellis saw the relationship between the painting and the live performance as fostering a level of engagement that grounds the text in physical action. As he describes, "They turned into 'something-that-you-read', into matter; they were meant to prompt a kind of life ritual..." (ibid). In this way we might see the theatre of staging the canvas stripping and singing the subsequent text as removing the static or suggestive qualities the medium may otherwise adorn its content with. Instead, the text, like the house-paint becomes matter to be handled and experienced, manifesting again that 'synesthetic response' and 'textured noise' Nicolin writes of.

This quality of highlighting materiality through action, though diverse in its expression, appears frequently throughout the oeuvre of the Arte Povera movement, and is arguably one of the defining features of much of the associated work produced in the 1960s. Spanning from 1967 to the mid-1970s the Arte Povera movement was initially heralded by curator Germano Celant as an artistic strategy promoting gestures "that don't contrapose themselves as art to life, that don't lead to the fracture and creation of two different planes of the ego and the world, and that live instead as self-sufficient social gestures, or as formative, compositive, and antisystematic liberations". Featuring work by Italian artists, with at times disparate approaches to materials and mediums, the movement is often spoken about as being united by the "poverty" of the materials artists used — that is, the tendency to use plaster and granite in place of marble, or as Kounellis famously did, to display everyday objects, such as sacks of maize and beans, as artworks. However, the reading of 'poverty' as relating to the materials alone has since been problematised by scholars and was pushed back against by the artists themselves. When pressed on the centrality of this framework to his practice in a 1979 interview, Kounellis stated plainly that, "It's not a question of materials" (159).

Instead, what is increasingly being reflected on in the literature, and was at the time seemingly very clear to the artists working within the Arte Povera movement, is that the 'poverty' of these works is often located not in the materials themselves, but in the relations they establish and perform — in concert with objects, the viewer, the gallery space and aspects of the world more broadly. We can thus chart from Michelangelo Pistoletto's mirror paintings to the chemical transformations of Gilberto Zorio's installations, the way in which the live, interactive and fluctuating aspects of the pieces are regularly foregrounded and constitute the structuring principles and conceptual core of the works.

The 2020 exhibition Entrare nell'opera: Processes and Performative Attitudes in Arte Povera took this understanding of the movement as its starting point, exploring some of the specifically performative and theatrical influences on, and trends within, Arte Povera. The exhibition's co-curator, Nike Bätzner, describes the general characteristics arising from these factors in the exhibition catalogue thus;

What is specific to Arte Povera is that objects play a crucial role in their actions, and that they operate with something, so that object and action enter into a mutually reinforcing relationship...The objects used are not mere props, but are more like partners of the respective subject, acting both as adversary and ally, while even the mise-en-scene comprise equal spatial devices rather than mere stage sets — thus tapping into the spaces of possibility (Sculptural Performance - Performative Sculpture 75).

This description resonates with Kounellis's work in particular, not least because the reference in counter-point to stage sets aligns with the artists own painterly framework for understanding his practice. Returning to the parrot perched in front of the metal sheet, we can see this mutually reinforcing relationship at play. The iron mounting, though physically static, is active in the composition as it is the feature of the work that renders the presence of the parrot expressive of a particular set of relations. Likewise, the parrot is engaged in visual dialogue with the space, the objects and, to a literal extent in the catalogue text, with its audience. As Bätzner suggests, this kind of relationality conveys a sense of possibility with regards to reconsidering the hierarchies that dictate the processes and outcomes of different modes of artistic engagement.

The most famous of Kounellis's experiments to this end is his 1969 piece, Untitled (12 Cavalli). The work featured twelve live horses tethered facing the walls of L'Attico. The gallery space, still bearing the large open-plan dimensions of its life as a former garage, exhibited the horses for three days (Fuchs, Larratt-Smith, et al). I start here discussing this work, not because it chronologically was a precursor to Kounellis's bird pieces (it in fact came later), but because it is the image of this work that has become symbolic of Kounellis's broader practice, and of the Arte Povera movement. Though grander in scale than the works featuring parrots, toucans or finches, it nonetheless shares these works' interest in the dynamics of framing the unexpected liveness of animals within the mediating frameworks of artistic convention. The Phaidon monograph on Kounellis suggests that the work "encapsulates the constitutive contradictions that structure all of his art. In it, organic and inorganic, human and nonhuman, mythic and everyday, nature and culture, ephemeral and eternal, history and the present are dialectically comprehended and united" (ibid).

In retrospect, Kounellis's precursory use of live birds can be seen as a nuanced expression of these tensions and the manner by which Kounellis unites them. Birds appeared recurrently in Kounellis's work in the late 1960s, with the first instance being presented in the exhibition Il giardino, i giochi (The garden, the games) at L'Attico in March 1967. The untitled work featured canvases adorned with white cloth roses, surrounded by a frame of twenty-four zebra finches housed in individual birdcages. As in 12 Cavalli and the aforementioned work featuring the parrot, we again see the variable expressivity of the natural world (the finches) placed within the structured framework of an aesthetic language (both the cages and the gallery space).

This relationship between the live component and the formality of the space it is contained in has typically been discussed with regard to Kounellis's work, in terms of its subversive effect and the potential for institutional critique it proposes. The play of stark contrasts in both the piece featuring finches and the work exhibiting the cacti and the parrot seems to suggest an antagonism between their live protagonists and the space they occupy. In a 1972 interview with Willoughby Sharp, Kounellis sought to explain the latter work as follows:

"The parrot piece is a more direct demonstration of the dialectic between the structure and the rest... The structure represents the common mentality, or the sensitive part, the parrot is a criticism of the structure, right?" (144).

Contrary to this framing, where the structured parts of the work are described as 'sensitive', it is the birds in Kounellis's work that may be considered the direct 'sensitive', or mutable, counterpart to the highly structured immutable elements. The latter is used to frame the former, seemingly elevating the natural phenomena to the plane of art through the (de)contextualising, impersonal iron scaffolds. It may then be seen to follow that the critique Kounellis is making is of the gallery space, and the tendency of art to create remove from that which it seeks to represent. Indeed, Kounellis's practice appears to challenge a limited view that would see art defined as a discrete system of representation necessarily aloof from the material reality of its content—that of art as opposed to life. But though Kounellis does have a critique of the gallery "as a bourgeois reality, as a social structure" (Structure and Sensibility 145), these works are not simply concerned with showing up the constrictive, formal limitations of the space in which they exist. Instead, Kounellis's interest appears to lie not with a critique of the confines of art, but in the expansion and sensitisation of the medium of painting.

We can see this in the way that the live animals in the work, in themselves pose a paradox with regards to the visual language of representation. Notably, these are not figures entirely alien to the language of art, and in fact in some ways are just a more concrete manifestation of imagery that has art historical precedence. Just as horses as a figure echo a long art historical lineage, featuring in portraits of nobility on horseback and the surrealist subconscious alike, the choice of birds resonates not so much with a single historical movement, but with the history of visual culture in general. In his book The Art of the Bird: The History of Ornithological Art through Forty Artists, Roger J. Lederer argues that birds have been a mainstay of artistic representation for over 40,000 years (6). Lederer identifies the wide variety of purposes they have served as characters in folklore, figures of myth, religious or moral symbols, and exotic ornaments, or decorative marginalia. Given this eclecticism, Kounellis's reference point in using birds repeatedly does not seem to be a specific one. Instead, it is the quality that has made birds such a consistent feature of visual culture that Kounellis is drawing on — that is, their innate aesthetic sense of drama and spectacle. Despite being a figure of nature, the movement, shape and colour of birds has consistently been used artistically to add a heightened, theatrical (at times symbolic or mythical) attribute to works of art, and it is this contradiction between the natural world and its theatrical expression that Kounellis uses to advance his conceptual project in the 1967 pieces. It is the dual character of the bird as being both naturally occurring, and yet a visually extravagant spectacle, that, in the context of Kounellis's work, proposes a rethinking of the art versus life divide. Because this capacity for the creature to be at once an aesthetic object and an unmediated, live subject implicates the austere iron structures that surround it in dialogue rather than dispute.

Further to this, we can again take as example the use of the parrot in the 1967 piece. The parrot, a creature often associated with its ability to perform mimesis, on one level acts as a conceptual stand in for the work of art in general, and as Kounellis is deploying it. We might think here of the archetypal scenario of marvelling at a bird's ability to imitate speech—to perform the lines fed to it by a human interlocutor. The uncanny, performative factor in this instance is the bird and its ability to mimic 'real' speech. The theatre of the situation elevates the bird to a position distinct from its reality as a thing of nature. It becomes a mirror to the actions and abilities of its human counterpart. In contrast, in Kounellis's work, the thing that is shocking or jarring is the appearance of this live creature in the gallery space. The mimesis being performed is an inversion of the typical talking parrot act. Because rather than reflect the content fed to it, the parrot, in the context of the gallery, is the genuine article — the element of the real — that art conventionally is tasked with repeating back to us in an affected manner. The purpose of featuring birds, or later horses, in these pieces then is to position the act performed by the work of art, as firmly grounded in reality. Like the artist's early works that rendered text and language material, the birds locate the structures they are installed in, in the concrete relations of the world as it exists beyond the affectations of the gallery space.

In this context, the works should not be understood simply as a juxtaposition of the organic against the constructed, or the real versus the represented. There is considerable interplay between these elements that undermines both the interpretation of the birds as purely 'natural', and the apparent rigidity of their framing device. This interplay is in service of Kounellis's expanded definition of painting. Writing of the use of birds in the works he argues, "They are alive, real, but above all they are signs of an image constructed on relationships; and, in the long run, they're both painting to me. I am asked if I'm a realist painter, and the answer is no. Realism represents while I present" (Black and White 100). In this way, Kounellis appears to be using the birds not as a subversion of the conventions of painting, but as a means of drawing out and amplifying its relational qualities — specifically its relationality with regards to the material world it is in dialogue with.

With reference to the conversation between Kounellis, the parrot and the children, Mario Codognato and Mirta d'Argenzio write;

The work... pushes the Western tradition of representation executed on the surface of a canvas to its breaking point. The parrot, a living creature, therefore no longer conforms to a code of representation but, rather, is "presented" in front of a metal structure, to play the role of a dramatic actor. In the same way, K. and the children stress its "sensitive nature" by the very act of holding an active conversation with it (8).

This notion of the bird as an actor is useful, in that it goes some way to accounting for the way in which it is both 'real' and alive, and also performative. It allows the parrot to be at once a presentation of the thing in itself, and a representation of a broader set of relations. Understood in this way, the bird is then not an affront to the limits of artistic expression, but a means of involving the viewer and the world they inhabit in a particular mode of expression. Its liveness, as the act of conversation with the parrot further elicits, opens the work up to incorporate the immediacy of the present and the act of reflection involved in engaging with it. It consequently renders the work as a whole, sensitive to the world, in a way that the distance required of painterly representation must ordinarily deny.

Reflecting on the 2015 exhibition at Galleria Christian Stein, Nicolin writes that Kounellis's work appears to, "presage a spate of recent works by artists ranging from Pierre Huyghe to Marc Camille Chaimowicz to Anicka Yi that have ushered living organisms into the gallery". While it is true that Kounellis's work with animals is formative in this regard, his practice and its context is significantly different to that of the artists Nicolin lists. This distinction is in part indebted to the framework of artistic poverty that Kounellis's practice developed in relation to.

Artists like Huyghe arguably use their artistic framing to make the natural components in their work seem alien and strange. Conversely, the artistic framing devices in Kounellis's work — specifically the use of theatricality and liveness — are employed as a means of grounding the spectacle of art in the everyday. Just as singing the text in his paintings was meant to transform the signs into matter, the intensity of that which is normally represented being a real, living, breathing entity in the gallery becomes a vector through which to see the encounter with the gallery as in concert with — rather than exempt from — the engagements of everyday life. This is consequently the characteristic of Kounellis's work that is 'poor' in the most artistically sophisticated sense of the term. In this way, looking at the role theatricality plays in Kounellis's bird works from the late 1960s provides a framework for interpreting the potential of birds as theatrical and aesthetic subjects, but also for understanding the concept of 'poor art' as a relational, rather than purely material, artistic strategy.

Moreover, it suggests that artistic poverty is not necessarily just a matter of stripping back the aspects of a work to its most basic elements. There is a sense of rich extravagance to the parrot's shock of blue and yellow plumage, or to bringing twelve horses into the gallery, and this is significant in terms of Kounellis's project and conception of himself as an artist. Although many have read works like Untitled (12 Cavalli) as an attempt to dismiss or break with the established language of artistic expression, there is no evidence that this was the artist's primary intention. Working in the theatre at the dawn of Italy's Nuovo Teatro movement, similar charges were levelled at Kounellis and his collaborators and he responded thus; "We have tried to rebuild theater. But do not talk to me about crossing limits. I don't know what that means. I have never overstepped limits" (Black and White 101-102).

This statement gestures towards the real triumph of Kounellis's expression of povertà, as the artist takes limits themselves as the material with which he rebuilds and reimagines what it means to make art in a particular space or medium. This is apparent in the concrete way in which the components of his work sit in stark contrast against each other, and the manner that, through their theatrical engagement, these points of contrast become the lens with which to see discrete objects relationally. Specifically, it is the tension between art and life that Kounellis situates in seeming opposition — the living parrot on its clinical metal perch, the cacti in their angular iron beds, the horses in the pristine white-walled gallery. Yet it is in, and in fact through, the establishment of these oppositions that he locates unity — the bird is an actor, the iron of the scaffold is elemental, a child's observations about art held in the same breath as their most basic urges and sensations ("I'm sleepy", "it hurts").

Historian Robert Lumley writes, "Kounellis shifts the frontier of what can be defined as art, but there is never the idea that art should be dissolved into life. On the contrary, art is given a new meaning as a rite of initiation through which to re-experience life" (34). This speaks to the way in which the language and limitations of art are not, in Kounellis's practice, so much undermined as they are incorporated into the work as a functioning feature of it. This too, is artistic poverty, as it connotes a practice that takes up and makes use of the very limits of its own expressive potential. Despite the theatricality of the compositions there is little excess, as the structuring principles of artistic expression, along with the likes of burlap sacks and text and exotic birdlife, are all made material and are legible in the visual field.

It is precisely for this reason that we might be inclined to believe Kounellis when he says — despite installing all manner of sculptures and live animals in the gallery — that he is a painter. Because it is through the theatrical friction of such contradictions and tensions that Kounellis sought a profound unity between his art practice and the corporeal qualities of the world beyond the gallery walls. And ultimately, while total unity of this kind may be 'difficult to attain...Utopian... impossible', the partial realisation of such an achievement can still be glimpsed in those contradictory encounters that fill the gallery with the smell of manure and soil and paint stripper, or the sounds of chattering children and twittering finches.

Works Cited

Bätzner, Nike. "Sculptural Performance - Performative Sculpture." Entrare nell'Opera: Processes and Performance Attitudes in Arte Povera, ed. Nike Bätzner, Maddalena Disch, Valentina Pero, Christiane Meyer-Stoll, Kunstmuseum Lichtenstein, Vaduz, 2019, pp. 75-86.

—. "Jannis Kounellis: Action as Vibrant, Fulfilled Duration." Entrare nell'Opera: Processes and Performance Attitudes in Arte Povera, ed. Nike Bätzner, Maddalena Disch, Valentina Pero, Christiane Meyer-Stoll, Kunstmuseum Lichtenstein, Vaduz, 2019, pp. 144-155.

—. "Jannis Kounellis." Entrare nell'Opera: Processes and Performance Attitudes in Arte Povera, ed. Nike Bätzner, Maddalena Disch, Valentina Pero, Christiane Meyer-Stoll, Kunstmuseum Lichtenstein, Vaduz, 2019, pp. 418-440.

Celant, Germano. "Arte Povera: Notes For A Guerilla War." Flash Art, Issue 261, July 2008, www.flashartonline.com/article/arte-povera/. Accessed 3 August 2022.

Codognato, Mario and d'Argenzio, Mirta. "Kounellis: The Ship in the Maze." Echoes in the Darkness: Jannis Kounellis Writings and Interviews 1966-2002, ed. Mario Codognato and Mirta d'Argenzio, Trolley Ltd, 2002, pp. 6-9.

Kounellis, Jannis. "'Hey! What's Going On? Hey!' (to the parrot) (1967)." Echoes in the Darkness: Jannis Kounellis Writings and Interviews 1966-2002, ed. Mario Codognato and Mirta d'Argenzio, Trolley Ltd, 2002, pp. 12-13.

—. "Techniques and Materials (1968)." Echoes in the Darkness: Jannis Kounellis Writings and Interviews 1966-2002, interview by Marisa Volpi, ed. Mario Codognato and Mirta d'Argenzio, Trolley Ltd, 2002, pp. 130-131.

—. "Structure and Sensibility (1972)." Echoes in the Darkness: Jannis Kounellis Writings and Interviews 1966-2002, interview by Willoughby Sharp, ed. Mario Codognato and Mirta d'Argenzio, Trolley Ltd, 2002, pp. 140-151.

—. "Interview (1979)." Echoes in the Darkness: Jannis Kounellis Writings and Interviews 1966-2002, interview by Robin White, ed. Mario Codognato and Mirta d'Argenzio, Trolley Ltd, 2002, pp. 156-177.

—. "Man of Antiquity, Modern Artist (1982)." Echoes in the Darkness: Jannis Kounellis Writings and Interviews 1966-2002, ed. Mario Codognato and Mirta d'Argenzio, Trolley Ltd, 2002, pp. 32.

—. "Black and White (1996)." Echoes in the Darkness: Jannis Kounellis Writings and Interviews 1966-2002, ed. Mario Codognato and Mirta d'Argenzio, Trolley Ltd, 2002, pp. 97-103.

Larratt-Smith, Fuchs, et al. "How Jannis Kounellis and 12 horses made an Arte Povera masterpiece." Phaidon, 2021. Accessed 3 August 2022.

Lederer, Roger J. The Art of the Bird: The History of Ornithological Art through Forty Artists, University of Chicago Press, 2019.

Lista, Giovanni. Arte Povera, Milan: Continents Editions, 2006.

Lumley, Robert. Arte Povera, Tate Publishing, 2004.

Merjian, Ara. "The Lingering Presence of Jannis Kounellis." Hyperallergic, July 2019. Accessed 3 August 2022.

Nicolin, Paolo. "Jannis Kounellis." Artforum, trans. Marguerite Shore, October 2015. Accessed 3 August 2022.