Becoming Bird: an artist's reflection on listening and making

by Dr Anna Walker

- View Anna Walker 's Biography

Anna Walker is an artist, researcher and storyteller based in the UK. She is a member of the Transtechnology Research group at Plymouth University, UK, and ARE (Artists, Resilience and Economy).

Becoming Bird: an artist's reflection on listening and making

Dr Anna Walker

Introduction

Becoming Bird is a journey through three artworks: The Language of the Birds (2018) by Genie Poretzky-Lee, Dawn Chorus (2007) by Marcus Coates and the recently completed video Becoming Bird 1: Spring (Walker 2022). The intention is to track the intra and inter-relational space communicated between humans and animals, in this instance birds. I am interested in the performative aspect of the artworks to determine what new and varied information can be disseminated and what the work requires of us, the audience. Moreover I will be asking how the performative can be used to negotiate current ecological dialogues, and create space for restorative reflection.

Erin Manning and Brian Massumi consider every artistic practice an activation of thought, for example, dancing is thinking in movement, and painting — thinking through colour. They regard writing as a productive interference that communicates within the fragile difference between modes of thought. "For it is in the breaching that thought acts most intensely, in practices co-composing" (Manning and Massumi viii). For Donna Haraway thinking-with leads to becoming-with and staying-with "naturalcultural [sic] multispecies trouble on earth" (Haraway 2008, 40).

In response, this essay functions on several inter-related layers. Linked always — though at times tenuously, the essay is about becoming through thinking, writing and listening. It is an entangled tale of interference, woven through and enfolded in the other; methodological abundance, which embraces autoethnography and connects to Michel Serres's notion of desmology, a medical term used to describe "not so much the state of things but the relations between them" (Serres 204). It also calls upon the tentacular thinking that Haraway employs to feel and to try to tell the story of the Chthulucene (31), differentiating the ecological philosophy where everything is connected to everything, from everything is connected to something, which in turn is connected to something else.

For example, I have grown accustomed to the many songs of a blackbird, perched at the top of a tall silver birch tree at the end of my garden. He was there through the past two years of lockdown and is still there no matter how the day unfolds. It is hard to imagine this little blackbird is singing to attract its mate, mark its territory and announce that he is healthy, vital and strong. The sounds he exudes are a harmonious medley intertwined with the distant faint noises of traffic, the call of a magpie that also sits atop the tree, and the sharp whistle of the red kites that circle above. Listening, I am aware of the differentiating tones between one and the other of the same species, and I wonder if I am imagining that they are singing individual songs. The cooing of pigeons is plentiful, almost like a chorus and I am reminded of Gertrude Stein's refrain: "The pigeons on the grass, alas, the pigeons on the grass alas", for a moment I am back in New York sitting in a seat at the Metropolitan Opera House (Stein). So, like Anna Tsing, in The Mushroom at the End of the World, I ask: "[c]an I show landscape as the protagonist of an adventure in which humans are only one kind of participant?" (Tsing 154) Will it change how one perceives something of the world? To do so, requires other ways of making worlds, alternative ways of listening and seeing. In Haraway's words: "Vocation: calling, calling with, called by, calling as if the world mattered, calling out, going too far, going visiting" (126).

As we advance with all of our messy humanness we participate in bringing forth the world in its specificity. It is therefore important that this entry into entanglement begin with a declaration of care, for "[i]t matters what ideas we use to think other ideas [...] what thoughts think thoughts." (Haraway 34-35). It is a journey that also calls for an embodied and practical approach, one that takes into consideration all of its connectors, its ligaments, and various assemblages: open-ended gatherings that move beyond the human to all species that occupy the same space. In Tsing's words:

Assemblages don't just gather life ways, they make them. Thinking through assemblages urges us to ask: How do gatherings sometimes become 'happenings', that is, greater than the sum of their parts? If history without progress is indeterminate and multidirectional, might assemblages show us possibilities? (23)

She goes on to explain assemblages in terms of polyphony, where to appreciate polyphonic nuances and subtleties one must listen to the separate melody lines and how they come together in unexpected moments of harmony and then dissonance. So too one must attend to the assemblages' many separate ways of being at the same time as watching how they come together in sporadic but consequential coordination. Assemblages coalesce, change, dissolve and re-form (23-25). Expanding Tsing's places of listening is to emphasise a specific type of listening, which is to say it is listening in as well as out to enlarge what is possible, to make important what is necessary, and to find other stories, other solutions beyond what is human. Here, listening-in leads to making, which in turn leads to writing; an entanglement — a mixed up nonsensical space of disparate and correlative thoughts, doings and eventual happenings. Writing is also a process of exploration, of finding something out from this continual becoming, locating in the in-between fragmented place something sensed but not yet known. In this instance, it is writing through to the making of the video: Becoming Bird, 1: Spring, (14 mins, 2022) and back to the word, which I will discuss in Proposition III. This kind of listening answers Maria Puig de la Bellacasa's insistence that care be an entry point into an embodied and practical ethics of moving through the world.

Thinking care as inseparably a vital affective state, an ethical obligation and a practical labour has been from very early on at the heart of feminist social sciences and political theory; an endeavour that has become more visible with increased interest in the 'ethics of care' (197).

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Proposition I

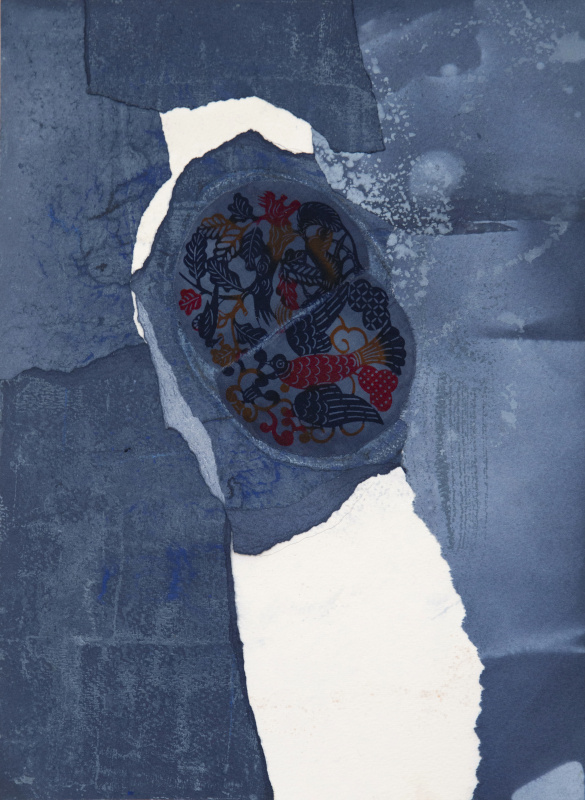

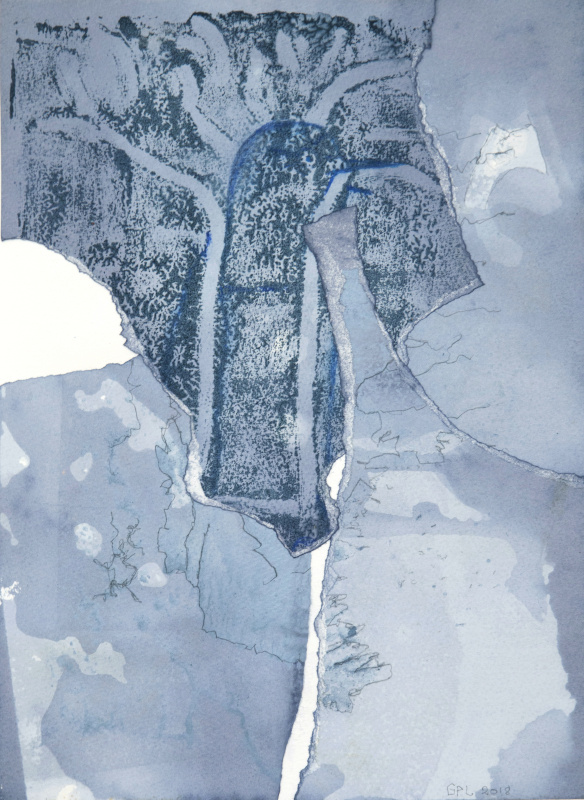

The Language of the Birds is a series of 30 monoprints created in 2018 by the artist Genie Poretzky-Lee. She was inspired by the secret language of the French medieval troubadours and the poem The Conference of the Birds (1177) by the Sufi poet Farid Ud-Din Attar (1145 - c.1221). The medieval troubadours were regarded as celestial messengers of love; bestowed with divine knowledge they travelled from the East to the West harbouring a secret language and a hidden doctrine. They were thought to be the inheritors of the Kingdom of Heaven — a mystical heaven known for its purity, noble life, and holy aspirations. Instructed to carry these mystical traditions of Eastern arcane lore from place to place, they did so through poetry, song, and musical composition. Similarly, in the Kabbalah, the language of the birds was considered the key to perfect knowledge (Bar-Asher 895-898). In Norse mythology, it was a sign of the ultimate wisdom (Guénon 172-175). The god Odin had two ravens — Huginn and Muninn, who flew around the world and told Odin what happened among mortal men; while Dag the Wise, the legendary king of Sweden, had a sparrow which constantly brought back news to him.

In a ritualised fashion of making, Poretzky-Lee repeatedly applied variations of woad paint — a natural blue dye, which contains low concentrations of indigo compounds — and powered pigment to a glass surface. She drew into the paint before pressing leaves, fabric and collaged pieces or sheets of paper to the glass. It was a ritual that moved between roller, ink, glass and paper. The artist then paused to let each one dry, reflecting on what other component was needed to achieve each image. It was a practice that proceeded for over two months until all 30 monoprints were completed. Through intention and contemplation, her process turned the repetitive nature of monoprints into a ceremonial dialogue between the artist, the birds the blue ink and the paper. Marks emerged, some faint, others purposefully mimicking the trail a bird leaves across a surface, tracking a pathway through the poetic and mystical words of Attar's poem. Poretzky-Lee's line, drawn into the woad ink surface, also maps her own physical and metaphysical journey as she moves between her studios in India and England crisscrossing the migratory pathways of birds. Her work exemplifies Natasha Eaton's nomadic theory of colour as a way to think about cultural exchange, tracking the line of flight of colour as and beyond a narrative subject (3). The work was created in London in 2018 before being safely stowed away in her luggage and transported across continents to Goa Museum in India for exhibition. It was as if she were carrying the birds from country to country, protecting them from their hazardous journey, birds like the European flycatcher, the brown-breasted flycatcher, or barn swallow that all fly from Europe to India in search of a warmer climate in the winter before returning to breed in the summer.

In Attar's poem, the birds of the world gather to decide who is to be their sovereign. The Hoopoe, considered to be the wisest of them all, suggests they seek out the mythical bird the Simorgh, which entails an arduous quest across seven valleys. Renowned Iranian poet and writer, Sholeh Wolpé describes how the birds hearing the description of the valleys become distressed, some even died of fright but still, they set off on their pilgrimage (17-18). On the way, many perished, and only 30 birds made it to the Simorgh and so there are 30 drawings, untitled and unnumbered, without hierarchy.1

The monoprints are not sequential, they do not follow a linear passage of storytelling, but nonetheless, there are hidden narratives embedded within the work. Each monoprint is layered with its own story. To fully appreciate the monoprints, and the imaginary world of wonder and myth that is embedded within each one, it is necessary to enter a space beyond the cognitive — to feel one's way into them, with tentacular progression. In Drawing Fig. 1, for instance, two semi-circles of finely printed fabric are collaged onto a patchwork of ripped and layered woad mono-printed blue paper. On the fabric, which appears to be flying off the edge at the upper left corner, two birds are printed in red, orange, and blue. They both eat berries from a tree. One of the birds looks like a pigeon, the other is much smaller, the species difficult to determine. There is a desire to feel the roughness of the torn edges, to touch the fabric and stain the fingertips with its blueness, as if nothing is fixed, and everything is mutable, transferable. The faint and ghostly markings of what could be another bird can be seen in the top left corner, perhaps one of the birds that perished in Attar's poem, and so remembering is required for all those species of birds that have been lost to extinction.

In Fig. 2, faint pencil marks and lines are reminiscent of country borders on maps and what could very well be the Hoopoe makes an appearance. In Poretzky-Lee's artwork this majestic little bird rises from a blue background, with a feathered crown embedded in a camouflage of leaves and tree branches. As Attar describes:

They argued how to set about their quest.

The hoopoe fluttered forwards; on his breast

There shone the symbol of the Spirit's Way

And on his head Truth's crown, a feathered spray (42).

In another monoprint, Fig. 3, a bird squawks as it wings its way over a pale blue surface, and on over the ghostly printed traces of a landscape. It is as if we are glimpsing the sweeping terrain through the eyes of the bird in flight. In four of the drawings, the artist has laid her hand and drawn around it, a signature perhaps, or a reminder to the artist to remain grounded on this imaginary and mystical flight. Applying a deeper reading this could well be the human imprint that threatens the journey of the birds. Climate change, the loss and degradation of habitats due to deforestation, industrial farming, and coastal corrosion have all left their mark on the rapidly declining species of birds. In the majority of her monoprints, the paper is torn. The tearing is the disruption of the rectangular edges to create a different relationship to the original white surface of the paper, it is also demonstrative of how we humans have torn asunder the surface of this planet, how we have disturbed the fine ecological balance of the earth to disastrous consequences. Each rip is an indication that there is no way back, once torn there is no reparation. That said each piece is a creation of something new that is not without potential. The layers that push up against or lie on top of each other are the artist's memories, accumulating year after year. The laying down of piece by piece of paper and then printed on top represents an intertwining of the past with the present, and a process to create new insights and new ways of being in the world. Though Attar's poem is present throughout the monoprints, it is not necessary to have read the poem to appreciate the many layers of story and verse embedded within the work.

In Language of the Birds, Poretzky-Lee was performing for and through Attar's spiritual journey, seeking out a language of love. Her drawings offer the viewer an experience based on her knowledge of the words of Attar, and their shared love for birds, which with their trials and challenges move through Attar's words and on to Poretzky-Lee's paper. It is a shared becoming through the performative action of both writing (Attar) and making (Poretzky-Lee). Through the artists' attentiveness, there is an intimate entanglement between materials, history, metaphysics and nature: an entangled becoming-with.

Figure 4

Figure 5

Proposition II

Dawn Chorus (2007) by Marcus Coates is an immersive 14-screen installation that explores the relationship between birdsong and the human voice and the similarities between animal and human behaviour. It was an ambitious project with scientific as well as artistic outcomes. Coates worked with scientist Peter McGregor and wildlife sound recordist Geoff Sample to capture a total of 576 hours of birdsong — valuable data recorded in a challenging and dense acoustic environment that contributed to an expanding archive of scientific knowledge on bird communication and song. Supported with funding from the Wellcome Trust, Dawn Chorus builds Coates's earlier work (e.g., A Guide to the British Non-Passerines, 2001), in which the artist endeavours to understand the natural world through quixotic mimicry. Coates hired a camper van, and with Sample, a 24-track digital recorder, and 14 microphones recorded six dawn choruses from 3-9 a.m. across three locations in Northumberland, England. With the microphones placed high in trees, low in bushes, and between rocks, each morning for a week they collected the songs of 14 birds.

Back in his studio, Coates slowed down the recordings. He then auditioned amateur singers to sing along with the new version of the bird song. He chose 14, and filmed each one at dawn in their homes or at the office, representative of their natural habitats. The singers pushed the boundaries of normalcy and challenged physical and social constraints. They sucked in air, grunted, hummed and clicked, singing along to the bird sounds for extended periods. Thereafter the recordings were sped up to the original 'bird speed'. The result was a host of characters that twitched and tweeted like real birds. A review in The Guardian by Viv Groskop described some of the responses from the singers involved in the project. Blackbird, aka Piers Partridge states:

It was quite meditative [...] I found myself going deeper and deeper into the quality of the sound. The blackbird had one or two favourite riffs, so I'd think, 'OK, here he goes.' I imagined myself as a blackbird on a spring morning, very early in a high place, having that freedom not to think but just to let the sound come out. With that came some interesting movements — I was cocking my head to look around. I felt really spaced out. When it finished I was miles away. (Groskop)

In 2015, the work was exhibited in its entirety (all 14 screens) at Fabrica Arts Gallery, Brighton. Coates, making connections between the Gallery's church interior and the quiet reverence of woodlands, installed the screens around the space at various heights and levels, mimicking the birds' habitation and the places where Coates and Sample had originally placed the microphones. Coates was utilising the human body as an instrument to understand something other. He was creating a place for the irrational and the magical, which was as much about discomfort as it was about animal metamorphosis and the surreal. Oddly moving, the work evoked the desire to understand through becoming. Through masquerade and sleight of hand, Coates, breaking down the barriers between animal and human worlds, is offering us, his audience, the opportunity to question what it means to be human.

Dawn Chorus is a mythical place of story and metamorphosis, an in-between space of possibility. It places the viewer into a state of uncertainty and doubt through this interaction with the other, and requires the viewer to listen and grapple-with to understand what it means to be worldly. His artistic practice draws on anthropology, mythology and empirical scientific methodology to create phenomenological experiences where dimensions tangle, and new potentials are created. Dawn Chorus, in particular, delivers a different kind of dialogue to engage with place and the creatures that occupy that place, that is, to rethink one's relationship to the birds, and to birdsong. In effect, Coates was asking how we reconcile the human animal divide to readdress the ways in which we have been culturally defined to separate ourselves from the natural world. Through Dawn Chorus, he was extending the possibility of becoming others, in the artist's words: "creating the opportunity for immersion, almost to a level of endurance, [...] They're performing this bird. They are becoming this bird" (Coates). This meeting place between bird (animal) and human is a making-up, a fabrication in order to understand. It is a seeking through attentiveness, a curiosity about the other, an occupying, shape-shifting process of inquiry — in Haraway's words an other-worlding (92).

In When Species Meet (2008) Haraway decries the lost opportunity when Derrida meets the gaze of his cat, which he describes in a lecture given in 1997, And Say The Animal Responded? In her words: "[...] he arrested that lure to deconstructive communication with the sort of critical gesture that he would never have allowed to stop him in his canonical philosophical reading and writing practices" (20-21). Where Derrida fails, Coates jumps in with an intersecting gaze, his passion and respect for birds undeniable. What I am left with, as a viewer, is the desire to follow the threads of the intimate entanglement of bird, bird song, bird habitat, and human in Dawn Chorus. Held within the work through the care and attention of Coates, there is tenderness, and gentleness, and though there remains still a binary position between humans and nature there is a blurring of boundaries that offers the potential to be in contact with the natural world in a completely different way, one where there exists the opportunity to recognise ourselves, and our humanity as experienced through every living thing.

Proposition III

The video, Becoming Bird. 1: Spring (2022, 14 mins), was created by the author in conjunction with writing this essay. The video is a layered sound and imagery assemblage that coalesces, changes and reforms in its journey across the screen. Through the work, I am extending the idea of knowledge — experiential knowledge — in an attempt to challenge the definitions of animal to human boundaries and the experience of being in a merged/shared world. The collection of footage and sounds began in February 2022 with a request to a group of colleagues and friends to leave voicemails or messages with and about the bird song they heard as they walked through parks, fields, or city streets. In exchange, I would call them and leave similar messages.

What started to filter through were the descriptions of colleagues' walks, their thoughts and intimacies, the sounds of bird song, the noise of the traffic and life as it unfolded around the walker as they carved a space through time and place. Through the voicemails that arrived from around the world, I slowly began to piece together the moving imagery; a journey North by train, the farthest I had travelled since the beginning of lockdown, became the main footage of the video. Other footage was retrieved from an archive I have been building since 2012, recordings made by colleagues, and found footage of birds in flight on YouTube. All of the imagery is layered, animated and/or slowed down. It flows across the screen in various formations, the boundaries of the black screen holding both the connection and disconnect of the divide between the human and animal worlds.

The sounds are assembled in various explorations of speed and volume. For example, the crows are slowed down, as is the call of seagulls, which is a faint underlying high pitched almost angelic sound that holds the sound-work together, (recorded in Plymouth in 2013). Also slowed down are field recordings of the wind, the rustle of the trees and the fall of rain. Woven into the background is the ghostly melody of the BBC's first known recording from 19 May 1924, of a Nightingale, accompanied by Beatrice Harrison as she plays the cello. Described as a duet between bird and musician, "a magical nocturnal event that captivated the nation, inspiring a million listeners, tens of thousands of fan letters and repeat broadcasts every year until 1942" (Alberge), but earlier this year it was revealed as fake. Harrison was performing for and with an understudy for the nightingale, (thought to have been Maude Gould, a whistler or siffleur known as Madame Saberon). Together they were becoming bird to understand birdsong, in this instance the nightingale's song (The inclusion of both the sound and the story — here and in the footnotes, is to highlight the steep decline of nightingales and other bird species due to climate crisis and loss of habitats, and emphasise the necessity of consistently naming and including as a matter of care).2

Underlying this project of Becoming Bird, 1: Spring, were several intentions. Firstly, I was asking others to focus and listen both into and out of themselves. Birdsong accompanies us, it is there in the background but through asking, it created a different kind of listening — listening with care and attention. In the beginning, the messages were a little forced, self-conscious, manufactured even, but as the project progressed and friends became used to the process, the performative element shifted into a sharing of self, and as the voicemails continued they become more reflective, increasingly interior.

Secondly, the project was about contact: being in contact with others, and inviting them to be in contact with me. After lockdown, being in touch felt important, caring for the self and each other. This notion of care expands to a care-full listening to others. The intimacy of hearing the messages through headphones extended to a consideration of the other's space, their thoughts and their walks. For example, listening to a message from one of the participants —musician Stacey Blythe, it was as if I was there in her garden observing through her eyes. This artwork is not about performing like a bird per se but rather about listening, becoming through listening and through noticing. It is also about building community, an expanding circle of listeners, telling a story through voicemails, and building an archive of care.

There is a contemplation of time: of time passing with the movement of the body through space, time stills in the listening, in the leaving of the message. These actions become, through their sharing, performative expressions of attentiveness, of listening and contact. It is a shared walking and seeing through each other's eyes that begins to include the birds as part of the story. We each move through the landscape differently, hearing with different ears, and paying attention with different eyes. When I hear the voicemails, I imagine the other bodies in motion, and as I edit, my listening deepens, I feel the position of their bodies, the thinking through their bodies. As I make, I reflect upon the spaces of encounter, the relationship between foot and ground, ear and the bird, the movement of the trees and the weather, and in the making, the embodying of others' knowledge, I both make and become the work. Writing now is part of that process, it continues the captured moment of voicemails, thinking through to visuals and words so that the voicemail is no longer finite, it moves on into another form. I become a witness to others' witnessing of time and place, and in so doing hold it dear. Telling stories about the landscape in this way is to know but a very small part of the landscape, nevertheless it is a beginning. It is absurd to think that this work will have any effect on the landscape but it is a dialogue with the reader, the viewer, and with the landscape. It is noticing.

Figure 6

Figure 7

Figure 8

The making of the video is performative. I collect first: compile an archive that is dated and organised into folders. I spend hours revisiting older entries in my archives sound snippets and video footage that I can reuse, animate, blend, or layer. There is a ritual to the seeking, a continual movement between mouse and keyboard, an intense period of looking, listening, sampling, and considering — flashes of imagery and snippets of sound that stay with me as I move through the landscape. As I seek and then walk, I am already layered with information. Becoming Bird, 1: Spring is therefore a building on other performative and learned actions, where my body is an archive in motion. Technology plays a vital role, in the collection of data and its storage, and of course the final video. The transfer of messages, images and sounds from phone to phone, and the means to stay in contact would not be possible without technology and yet I am acutely aware of how technology and its expansion destroys animals' habitats and depletes the earth's resources, and how it has changed the landscape I walk through.3 It is a conundrum that bleeds into the video, evidenced in the distortion of voice, the visual and sound noise from the lo-fi collection of data, and at times the confusing layering of voice upon voice, or voice upon sound. It is disturbance, interference.

Respect, contact, and attention are all part of this making practice. The finished video is an assemblage made up of the landscape, dreaming, imagination, noticing, listening, seeing, and consideration. In Becoming Bird, 1: Spring I am asking through listening to the world in this way, can an appreciation of the other, a different other lead to empathy? Can sharing and being in contact with one another expand to a consideration of the other that is not human, that is animal and nature? This video, like Dawn Chorus by Coates, and The Language of the Birds by Poretzky-Lee is a becoming-with to journey or travel another trajectory to uncover answers that our humanness and individual limitations prevent us from seeing, hearing or thinking. Compassion and empathy are necessary for change, walking in the steps of the other means to embrace a different way of being in the world. What does it mean to hold a fallen feather in your hand and wonder where it came from or ask where the bird that dropped it now resides? To imagine this is to imagine flight, which in turn is to see from above and gain another perspective, to make the elusive and intangible other (animal or bird) more real through embodied and performative storytelling. In Karen Barad's words:

The body reacts to the forces, manifest as shifting material alignments and changes in potential, and becomes not simply the received but also the transmitter or local source of the signal or sign that operates through it (189).

Finally:

Tsing, Haraway and Puig offer us the potential to understand care itself as a vital practice of critique. In Van Dooren's words: "Care-full curiosity opens up an appreciation of historical contingency: that things might have been and so might yet still be, otherwise" (291). The artworks I have presented here all speak from that place of care-fullness. They all share a desire to commune with, communicate, listen, interpret and speak to the birds. Each artwork in its own right is an intimate entanglement operating as part of Karen Barad's overarching spacetimemattering, where there is no absolute inside or absolute outside, rather it is "[...] a coming into contact with the 'exteriority within', a realisation of the active embodiment of matter, of 'being in the world in its dynamic specificity'" (Barad 377).

Hannah Arendt notably wrote: "To think with an enlarged mentality means that one trains one's imagination to go visiting" (43). Similarly, Haraway writes about the importance and the dangers of training the mind to venture off the beaten path to meet unexpected, non-natal kin, and "to take up the unasked-for obligations of having met" (130). All three artists and artworks ask: how can we reimagine our relationship to the non-human natural world, to save it from our destructive actions, placing care at the centre of our critical work?

The Language of the Birds makes real the Poretsky-Lee's metaphysical interaction with Sufi poet Attar's spiritual engagement with the world. Dawn Chorus actuates a space that isn't limited by one's self-consciousness or one's conscious thinking. Coates' participants, by dissolving themselves into bird, become bird, creating a space for the viewer to experience what it is to be bird. The artist's skill lies in the creation of an encounter that bridges the human-animal divide. Through his work, he journeys to another realm to retrieve useful and considered knowledge. The video, Becoming Bird, 1: Spring, continues this dialogue, activating a different notion of care for thinking and living in more than human worlds; in Puig's words: "Care is not about fusion; it can be about the right distance" (5). But the work of these artists is not without friction, just as reclaiming care in a new formation exposes real tensions. It involves acknowledging our participation in perpetuating dominant values and being humble enough to admit our wrongdoings to engage in new dialogues, cultivating — to borrow a phrase from Haraway — response-ability (130).

Works cited

Attar, Farid Ud-Din. The Conference of the Birds. Penguin Classics, 1984.

— The Conference of the Birds. Translated by Sholeh Wolpé, 2017.

Alberge, Dalya. "The cello and the nightingale: 1924 duet was faked, BBC admits" The Guardian. Fri 8 Apr 2022 10.44 BST.

Arendt, Hannah. Lectures on Kant's Political Philosophy. Ed: Ronald Beiner. The University of Chicago Press: 1982.

Barad, Karen. Meeting the Universe Halfway. Duke University Press, London. 2017.

Bar-Asher, Avishai. "Ornithomancy in Medieval Jewish Literature". Prognostication in the Medieval World: A Handbook, edited by Matthias Heiduk, Klaus Herbers and Hans-Christian Lehner, Berlin, Boston: De Gruyter, 2020.

Coates, Marcus. "George Stubbs: 'all done' from Nature." Comparative anatomies at MK galleries. Co-organised by the Paul Mellon Centre and MK Gallery, Milton Keynes 17 January 2020.

Eaton, Natasha. "Colour, Art and Empire. Visual Culture and the Nomadism of Representation." I.B.Tauris and Co. Ltd, 2013.

Groskop, Viv. "Chirps with everything." The Guardian. Thu 25 Jan 2007 14.26 GMT April, 2022.

Guénon, René. "The Language of the Birds" The Underlying Religion: An Introduction to the Perennial Philosophy. World Wisdom, Inc. Edited by Martin Lings and Clinton Minnaar. 2007.

Haraway, Donna. Staying with the Trouble, Making Kin in the Chthulucene. Duke University Press, 2016.

— When Species Meet. University of Minnesota Press, 2008.

Manning, Erin, and Massumi, Brian. Thought in the Act. Passages in the Ecology of Experience. University of Minnesota Press, 2016.

Puig de la Bellacasa, Maria. Matters of Care. University of Minnesota Press, 2017.

— "Nothing Comes Without Its World: Thinking with Care." Sociological Review, 60:2, 2012.

Serres, Michel. "The Art of Living." Hope: new philosophies for change, edited by Mary Zournazi, Lawrence and Wishart, 2002, (PDF).

Stein, Gertrude, and Thomas Virgil. Four Saints in Three Acts. 1928, Website.

Tsing, Anna. The Mushroom at the End of the World. Princeton University Press. 2015.

Van Dooren, Thom. "Care." Living Lexicon for the Environmental Humanities. vol. 5, 2014.

Footnotes

- Simorgh in Persian translates as thirty birds, and at the end of their journey, the birds learn that they are the Simorgh, that the "majesty of that Beloved is like the sun that can be seen reflected in a mirror. Yet, whoever looks into that mirror will also behold his or her own image" (Attar 2017). ↩

- Nightingales have a rich repertoire of sounds, able to produce over a 1000, compared with about 340 by skylarks or 100 by blackbirds. The brain of the nightingale responsible for creating sound is bigger than in most other birds. There are over 600 million fewer birds in Europe than there were 40 years ago. While the decline is levelling off, some of the continent's most-recognisable birds are among the worst affected, with house sparrow populations declining by half. Europe has lost almost a fifth of its birds since 1980 as habitat destruction has wiped out the animals' homes. ↩

- "Think about your cell phone. Deep in its circuitry, you find coltan dug by African miners, some of them children, who scramble into dark holes without thought of wages or benefits... No companies send them; they are doing this dangerous work because of civil war, displacement, and loss of other livelihoods, owing to environmental degradation." (Tsing, 2015, 134) ↩