Follow the Blind, Mimic the Wind, Become a Worm: Sonospheric Mappings by a Bag-Lady Soundwalker

by JANNA HOLMSTEDT

- View Janna Holmstedt's Biography

Janna Holmstedt is an artist and researcher interested in listening as a situated practice, the cultivation of care and environmental attention, human-soil relations, and composition in the expanded field of genre-disobedient art practices.

Follow the Blind, Mimic the Wind, Become a Worm: Sonospheric Mappings by a Bag-Lady Soundwalker

by Janna Holmstedt

Figure 1

FLOCK, FREQUENCY, COLONY

The restricted frequency range of human perception effectively limits what we deem worth listening to, and also what we habitually might consider part of our "flock" and thus are prepared to give a (political) voice. If we take feminist posthumanities seriously, which I intend to do, humans have never been "human," (Haraway, 2008, 305) and the human flock consists of more-than-human assemblages and symbiotic relations down to the smallest cell (Tsing et al, 2017). We are holobionts (Margulis, 1991). From this point of view, the environment is not something "out there" and "I", at a closer examination, turn out to be a multispecies colony. The words "flock", "frequency", and "colony", for me function as hooks for the imagination, or points to circle around, while critically and creatively imagining possible more-than-human relations, less colonizing settlements, and reflecting on our ability and inability to tune in to other frequencies than the human.

This essayistic journey will relate notes, thinking-doings, images and stories from an ongoing research process that harbors several sub-projects. Thus, there are many beginnings and trajectories. Rather than laying them out in a storyline, I present a bundle, a collection of telling "things" that have been gathered in my carrier bag on a homeward journey. With this bundle, I hope to evoke a resonant spacetime where a sonospheric sensibility can be traced and made sensible. The journey seeks to explore what it might mean to become sonospheric communards, membranes, where listening and following can be seen as forms of participation, not necessarily as in social interaction with other human beings but as co-habitation and participation in a shared environment. Acts of following (Kontturi, 2018) and listening are closely related in that both encourage receptivity and openness in a dynamic process of touching and being touched, changing and being changed. Homeward, in this context, refers to practices through which a sense of belonging can emerge, neither through claiming a territory, nor through a search for roots.

Ursula LeGuin's writes in "The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction" (1989) about the bag as a container technology that manages to hold and harbor the diverse and contradictory that emerge from a nomadic practice of wandering and gathering. This is in contrast to dominant narrative forms that are driven by conflict and follow the logic and trajectory of the heroic spear in the quest for new territories. With LeGuin's striking and amusing wordings, the technology of the spear "[is] starting here and going straight there and THOK! hitting its mark (which drops dead)." Donna Haraway cracks this carrier bag theory into a new materialist and feminist research method, the bag-lady practice of storytelling, where the unexpected, frail, diverse and irreducible is gathered into bags or bundles that create "messy tales to use for retelling, or reseeding, possibilities for getting on now" (Haraway, 2013). In turn, the wanderer and gatherer in this essayistic journey twists this line of thinking further, into a bag-lady practice of soundwalking. In the bundle of tales that I offer you here, we find experiments in interspecies communication, sensory deprivation, deep listening, the echolocation clicks of a blind woman, Eros, earthworms, and seeds of zea maize.

Now, let's start to drift.

Figure 2

FLOCK

The pack, the horde, the gaggle, the troop

The swarm, the throng, the crowd

The school, the pod, the nest, the pace

The clowder, the army, the smack

The glaring, the brood, the rag and the bask

The murder, the litter, the bunch

The gang, the skulk

The band, the bale

The pride, the muster, the crash

Companion or parasite?

"I", a hive, a composite

My body a colony, a teeming dark ecology

Flock, flockings

The cry of the flock

Flocculate

1.5 kilos of microorganisms

10,000 different species

"I", a nomadic, interspecific fraternity

I sit in an anechoic chamber, surrounded by an intense muteness. Nothing penetrates these sound proof walls. Nothing reverberates. If I close my eyes and let my vocal cords vibrate (singing, humming), I can feel how the room shrinks. The walls close in, and my voice hovers just outside my mouth.

There is a whale that sings at the wrong frequency, 52 hertz--unusually high-pitched for a baleen whale. Humans have tuned in to its song since 1989, but no one has ever seen it. It might be a blue whale. It might be a male. Attempts have been made to find Blue 52, who has been called the loneliest whale in the world. It is assumed that if it sings at the wrong frequency, no one of its own kind will ever hear it.

It may be that Orcas do not perceive themselves as separate, that their sense of self is distributed among them. The self is spread throughout the pod. Orcas synchronize their breathing and form a circle as they submerge their bodies in the water to rest. Like other dolphins, they sleep with one hemisphere of the brain at a time.

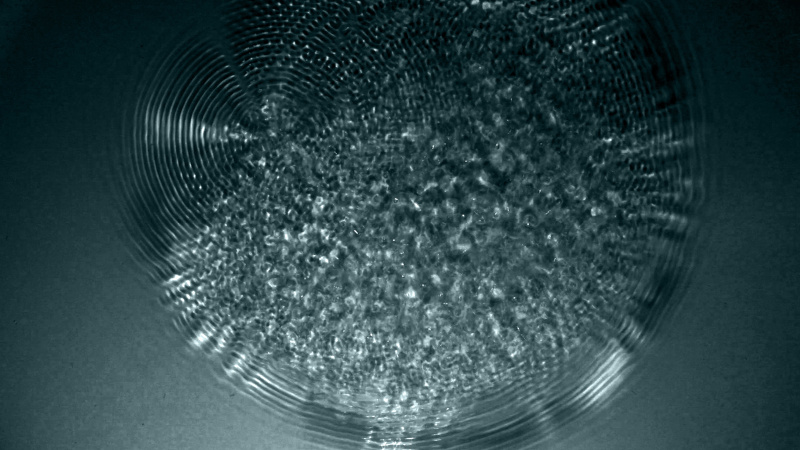

Figure 3

FREQUENCY

The Nonhuman Voice

-You be good. I love you, says Alex.

-I love you, too, says Pepperberg as she prepares to leave the lab.

-You'll be in tomorrow?

-Yes, I'll be in tomorrow, Pepperberg replies to Alex, an African grey parrot, after yet another day of work together.

-I can can I I everything else, says Bob.

-Balls have zero to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to me to, says Alice.

(FACT CHECK: Did Facebook shut down an Artificial Intelligence experiment because chatbots developed their own secret language?)

In November 1961--eleven years before the spacecraft Pioneer 10 was sent out into space with a message from humanity--a prominent flock of researchers were invited to a semi-secret conference arranged by NASA's Space Science Board to discuss a subject not yet considered scientifically legitimate: What are the conditions required for establishing contact with other worlds? (M0786, 1961). Carl Sagan had invited Dr John C. Lilly because of his pioneering work with dolphins and his thought provoking question: if we are unable to communicate with another intelligent species on our own planet, how could we possibly communicate with an alien? To suggest that an animal could be intelligent was at this time controversial. Nevertheless, the idea that engaging in communication with dolphins could prepare humans for an encounter with nonhuman intelligence was worth considering. Inspired by Lilly, the conference participants dubbed themselves as belonging to "the Order of the Dolphin" (Baur, 1975).

The day when communication is established, the particular other species becomes a legal, ethical, moral, and social problem ... They have reached the threshold of humanness, as it were.

(Lilly,1961, 211--212)

Lilly's curiosity about dolphins did not start either with questions of interspecies nor with extra-terrestrial communication, he was interested in their large brains. As a respected neurophysiologist in the 1940s and 1950s, he had mapped the brains of monkeys at the National Institute of Mental Health (NIHM), Maryland, USA, and dreamed of creating a brain-recording machine. His team had penetrated the skulls and grey matter of living animals with electrodes in order to register behavioral reactions to electric stimuli. In 1951, Lilly managed to create a "brain-television" using a cat (Lilly, 1950). Electrodes were connected to glow lamps by which the live activity of the cat's brain was made visible as a series of moving forms, shapes, and figures--the mysterious workings of the brain were written with light in real time. But that which had started as an attempt to map the remarkably large brain of the bottlenose dolphin would eventually transform into a high profile interspecies communication research project and the establishment of Lilly's own dolphin research facility, the Communication Research Institute (CRI), partly funded by NASA. The turning point came 1958 with the unexpected appearance of an animal voice, when a dolphin in the lab--fixed in a cradle on dry land and stimulated with electricity--suddenly seemed to imitate the researchers. If the scientists in accordance with scientific training and tradition were accustomed to think of themselves as modest witnesses (Shapin and Schaffer, 1985), who objectively reveal and articulate the wonders of a mute natural world, they would here suddenly find themselves in a situation where that mute otherness started to speak back. Donna Haraway has referred to this scientific ideal of modest witnessing as one of the founding virtues of modernity, which authorizes the scientist to become a "ventriloquist for the object world" (1997, 23--40). In Lilly's lab though, the ventriloquist's mute doll had come alive.

Lilly later wrote about the incidence that they had felt the uncanny "presence of Something, or Someone who was on the other side of a transparent barrier which up to that point we hadn't even seen" (Lilly, 1963). After this occurrence, the dolphins were referred to by names rather than numbers and Lilly decided to replace the electrodes with sound recording equipment. Instead of stimulating their brains with electricity, the dolphins were in various language lessons encouraged to mimic human speech with their blowholes. But to produce evidence of the dolphins' mimicking abilities in the form of recorded sound objects was not as easy as one might expect. The shift in technology and sensory domain, from visual to aural, would confront Lilly with an array of problems. Apart from the limited frequency range of the recording and playback technology, human hearing was in comparison to dolphins very restricted. The dolphins seemed to figure this out fairly soon and adapted their soundings accordingly. In addition, their vocalizations were extremely rapid. Even though the dolphins' speech was intelligible to Lilly and his research team, they discovered that, when recorded and played back to other researchers, the articulations were not clearly evident, or even recognizable as words. In order to overcome some of these obstacles, the researchers started to manipulate the tapes, slowing them down and thus altering the pitch to make the mimicking attempts more audible to a human ear. These manipulations of sound material would spark a series of elaborate sound and listening experiments where Lilly tried to extract the signal from the noise. But the attempt to amplify the uttered word and make it more clear and distinct seemed to have the opposite effect, even if it was articulated by a human. When Lilly created sound loops of cut-out words and played them back to observers who reported what they heard during extended listening sessions, the signal instead seemed to produce noise, as the observers did not only report one word, but thousands of them. Lilly also played his sound loops for educational purposes in some of his lectures and noted that they caused around ten percent of the audience to trip out (Lilly, 1972, 65).

Womb Music

The body is the first archive, the first recorder. That is what I am thinking while browsing through the content of box after box in Lilly's research archive, i.e. the John C. Lilly Papers at the Department of Special Collections and University Archives at Stanford University Libraries. Occupying almost 74 meters, the archive contains 116 boxes with documents and photos, and 1432 reels of magnetic tape, with over 800 hours of recordings of dolphin experiments conducted between 1961--1968. Every day at noon automatic sun blinds roll down to shade the enormous windows, their descent marking the passage of time. I can feel the baby tumbling in my belly. I am a metronome, my body and bones function as an instrument and amplifier where a continuous pattern of strong and weak beats--heartbeats and breathing--is produced. This is womb music, vibrations transmitted by amniotic fluids to the ear and the skin of the foetus. The first waltz is created by a muscle:

LUB-dub-( ) LUB-dub-( ) LUB-dub-( )

The fetus literally floats in sound, touched by voices, rhythms, noise; the vibrations envelop not only its ears, but resonate through its bones and skin. My speech is heard in the womb as melodic patterns where consonants disappear, accompanied by gurgling from the intestines, swallowing, digestion, and the sound of blood flowing through the umbilical cord. The fetus, six months old, has already started to be able to distinguish my voice from others, speech from music, and it attunes itself to the prosody of the Swedish language. The uterus is all but silent. Its acoustic environment and watery sonosphere creates a template for recognition, forming emotional patterns tied to pulse, variations of timbre, frequency range, and amplitude. The human mind is a musical mind, born in and from a tactile, acousmatic situation of vibrating skin, bones and fluids (Snowdon and Teie, 2013; Ullal-Gupta, et al, 2013). This reminds me of Peter Sloterdijk term sonospheric communard: "In the wall-less house of sounds, humans became the animal that come together by listening. Whatever else they might be, they are sonospheric communards." (Sloterdijk, 2011, 520). We become members of this sonic commune not necessarily through speaking, but through listening to the sounds of our environment as well as to the sounds we jointly make. With his spherology Sloterdijk attempts to develop a spatial vocabulary of inter-psychic space and a theory of relationality, or a theory of the shared inside. Not surprisingly, he refers to the mother-child (and fetus) relationship as a prototype for his theory, arguing that the model of subjectivity emphasized in a Western philosophical tradition since the Enlightenment disregards a primary intimacy, instead prioritizing a "cerebral individualism," i.e. the belief in a solitary, autonomous brain (Sloterdijk, 2011, 265). Though spatially oriented, it strikes me that Sloterdijk's theory is guided by a sonic sensibility. It is a sonic spatiality he brings forth, which serves to avert the gaze and its claims on the subject matter.

Etymology is playing tricks on me, the Greek word for womb and vagina is delphys, closely akin to the word delphis (dolphin). In addition, Delphi was the place where the oracle Pythia gave her body over to voices. Neither ventriloquist nor a doll, her body became a medium through which the incomprehensible sought to be articulated. At CRI, the dolphins tried to form and adjust their blowholes and bodies in various ways to produce the sounds they perceived. "R" could be imitated if the blowhole was partially submerged in water, which caused a rolling and bubbling sound to emerge.

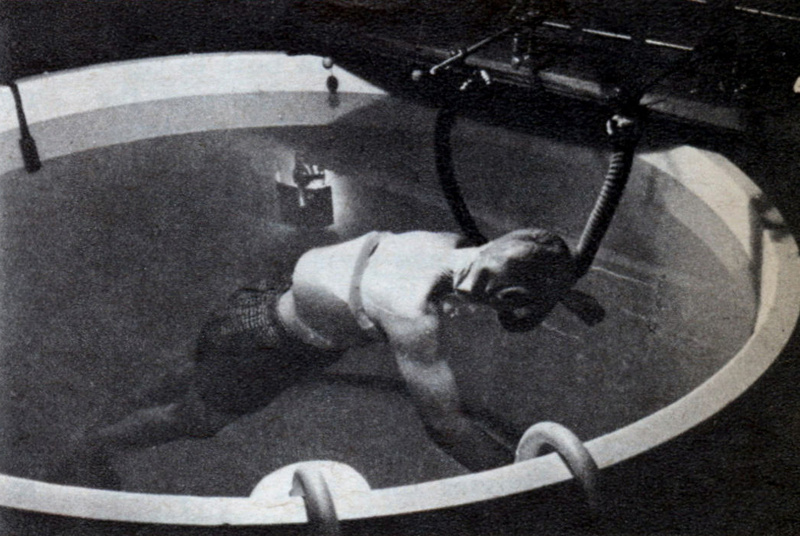

Figure 4

ECCO

In parallel to his early work on the dolphin brain, Lilly had conducted research on the effects of sensory deprivation, which would both influence and spur his interest in dolphins in unexpected ways. Lilly wanted to, through sensory deprivation, test two conflicting hypotheses that were dominant at the time about the mind and the brain. Does the brain need stimulation from external reality for consciousness to remain active? Or, is the origin of consciousness to be found in the brain's cell circuitry itself? In short: would consciousness "shut down" if external physical stimuli were to be reduced to the lowest possible level? To investigate this, he invented a technique where the subject was not merely physically isolated in a dark and silent cubicle as in earlier sensory deprivation experiments, but suspended in water. At NIMH Lilly found the perfect conditions, a sound proof building with a pool. In these experiments, Lilly developed a respiratory mask, which he tested together with different floatation devices [1]. Lilly used the pool himself regularly from 1954--1958, partly for self-analysis as he regarded the sessions in the tank to be a continuation of the psychoanalytic work he had done between 1949--53. He also saw it as an opportunity to study the brain and the mind from within rather than probing it externally with electrodes. It was quite clear from his very first experiments that the brain certainly did not shut down, and that the isolation and sensory deprivation resulted in a rather frightening experience. As earlier research on humans had shown, isolation could result in psychosis. After intense training to overcome his initial anxiety, Lilly found that the solitary confinement offered the most profound relaxation and rest that he had ever experienced. He also saw the floatation sessions as a form of mental training through which preconceptions about dolphin consciousness and limiting ideas about the nature of human consciousness could be overcome. Lilly attempted to approach dolphin-ness by surrounding himself with water. He also nurtured the idea that floating in solitude in the tank somehow simulates how the dolphins experience the world, as a pure mind in the waters. With sensory input brought down to a minimum (auditory, visual, olfactory, tactile), and with his body suspended and relaxed in lukewarm water, the boundaries of the body seemed to dissolve and the mind expand. He was able to enter into altered states where he left his human body behind. For Lilly, this was transformative. Nevertheless, for many years he was careful about what he said publicly regarding these very personal experiences. In this way, he somewhat unexpectedly began his journey as a psychonaut, which would come to influence his scientific research considerably. Or, as he himself put it: "Research at the frontiers of science is not a clean-cut, dry, planned affair" (1961, 208).

Is this a simulation of the brain in a vat? Or, is it an American version of Heidegger's hut, a hyper-hut, where some real thinking can be done--not in the "provinces" as Heidegger phrased it, but at the very "frontier"? Or, do we yet again witness a staging of the age-old Cartesian quest of going inward and giving up all relationships in search for pure knowledge that can be brought back to society and presented to other human beings "out there"? Although extremely monotonous, Lilly's set-up did not delete sensorial input; the skin becomes utterly sensitive in this watery condition. Rather than sensory deprivation, I would call it sensory Verfremdung, i.e. an act of making strange [2]. What did he encounter then, when he sensed he was finally freed from his body? A nonhuman intelligence. Lilly would many years later describe the transformative experience at NIHM in 1958 as the "Conference of Three Beings." The beings represented an organization that Lilly called ECCO, "Earth Coincidence Control Office" (Lilly, 1997, 109--115). In his artificial delphys, Lilly became a vessel for extraterrestrial voices.

If for Lilly the traditional distance and barriers between the scientific observer and the research object began to crumble around 1958 following his encounter with first Someone and then ECCO, the defining lines between science, ethics, politics, metaphysics, and mysticism began to blur as well. Everything mixed. Lilly became increasingly convinced that cetaceans are sensitive, compassionate, ethical, philosophical beings, and are keepers of a long-held oral tradition. Lilly would eventually come to see dolphins as superior to humans in intelligence. From the 1970s onwards he opposed the exploitation of animals when he was struck by the realization that at CRI he himself had operated a concentration camp for his friends (Lilly and Lilly, 1976, 200). He became politically engaged in protecting animals and their natural habitats, and, after been considered persona non grata in scientific circles, he re-emerged as a media celebrity--now in the guise of a New Age guru. On a more scientific note, Lilly concluded that dolphins are acoustically oriented and that humans are visually oriented, thus referring to how well-developed the brain is in various mammals in terms of processing aural versus visual impressions (Lilly, 1978). At the same time, I suggest, his remark touches on how a traditional Western knowledge system, informed by an ocularcentric and textual logic, is structured and staged, i.e. how well (or ill) adapted the academic knowledge apparatus is when it comes to accommodate multimodal, dynamic, situated and generative processes and knowledge practices that literally asks us to come to our senses. Lilly actively tried to erase the influence of the senses, as they contaminated the research results. Despite his attempts at breaking out of limiting frames of mind, and his willingness to accept the existence of nonhuman minds, he completely neglected both bodies and environments. Yet, to set up a simple opposition between seeing and hearing and divide the sensorial tangle into discrete channels, which in turn are designated to represent different faculties (such as intellect and affect for example), echoing what Jonathan Sterne has called the "audiovisual litany" (2012, 9), would be too simplistic [3]. Rather, Lilly could be described as belonging to a visualist tradition that, as Don Ihde has pointed out, stems from the classic period of Greek philosophical thought that elevates sight and links vision with thinking. This reduction to vision is, according to Ihde, "complicated within the history of thought by a second reduction, a reduction of vision" that separates experience from the real, or sense from reason in modern metaphysics (2007, 8-9).

Figure 5

SONOSPHERIC MAPPINGS

Sonic skin

I am in London for a short visit. While trying to navigate the Underground -- an unfamiliar, noisy and visually intense environment-- I follow a blind woman getting off the tube. I literally follow in her footsteps and attune myself to her body, imagining what it might be like to be blind. Suddenly, I become aware of the surface beneath the soles of my feet as we pass over the rough area that marks the platform's edge. The field of sound shrinks radically as we approach and are funneled up the stairs. The sound of her cane, which taps rhythmically on the wall, becomes quiet when the staircase ends and we round a corner; the tapping resumes when the stairs continue. I have difficulty keeping up with her as she moves skillfully through the sea of people. The sight of her back serves as a mental sound amplifier. When I narrow my gaze, it is as though I have suddenly turned up the volume or pressed a high definition button. I am surprised by the impact of this imaginative act on the field of perception, and how clear and immediate sounds become. The woman's cane is not just an extended arm, it even produces echolocation clicks where the place's architectural space, material, and character emerge around the body in motion. Although I focus my gaze on her back in front of me it feels like I have the omnidirectional vision of a fly. It is as if I, for a moment, saw and heard with my skin. The skin becomes a global sense (Serres, 2009) that both contains and connects--a porous border between what I habitually call "me" and the "environment". I am not pretending that through this sensory experiment I know what it is like to be blind, but I am learning something about listening.

This is not a shared inside, as Sloterdijk called it. Instead, in and through listening, I experience a mingling of world and body. Through the skin, I live the paradox of being neither inside nor outside. I become not only a member of a sonic commune, but also a membrane in a sonosphere. Michel Serres suggests that we approach the senses as discrete variations, knots, and sites of exchange. "Each sense, originating in the skin, is a strong individual expression of it," he writes (2009, 70). At the same time the skin receives all the senses together, in this the global skin-sense all the senses, in themselves mingled, flow together. In turning one's attention to one sense organ alone, certain aspects could be said to be amplified, yet still perceived in and through the skin. Sound has the power to penetrate through, even dissolve, what we usually conceive of as the borders of the physical body. It troubles boundaries in both fruitful and threatening ways. Opening up to the intimacy and vulnerability that listening implies might therefore also evoke a fear of being exploited and manipulated, of losing oneself.

Anne Carson writes in Eros the Bittersweet about a certain awareness of edges and their dissolution, which she connects with the use of a new technology, i.e. the written alphabet, and with Eros. "Eros is an issue of boundaries," she writes, "he exists because certain boundaries do" (1998, 30). The experience of desiring love is a paradoxical condition of losing oneself and finding oneself at the same time. Eros is lack, a desire for that which we never knew we were missing. Writing too is an issue of boundaries. With writing comes an intensified awareness of the self, the bounded entity both appears and dissolves in writing. With writing, as with desire, arises a heightened awareness of that which separates. This awareness of edges can, Carson writes, be seen in ancient Greek lyric poetry, and she asks: "Is it a matter of coincidence that the poets who invented Eros, making of him a divinity and a literary obsession, where also the first authors in our tradition to leave us their poems in written form?" (1998, 41). Thus she begins her inquiry into writing and its consequences. Language, as well as the senses, are radically altered and reoriented in the process of alphabetization. "A written text separates words from one another, separates words from the environment, separates words from the reader (or writer) and separates the reader (or writer) from his environment. ... written words project their user into isolation" (1998, 50). From this isolated position, the textual practice of separation could be said to be projected back onto reality. This strikes me as a perfect description of Lilly's efforts to isolate the scientific observer, in an attempt to escape both the body and the outer world. In Greek lyric poetry Eros is described by metaphors such as melting, roasting, crushing, piercing, or bridling. Carson here traces "a sensibility acutely tuned to the vulnerability of the physical body and of the emotions or spirit within it" (1998, 41). And, continues:

As an individual reads and writes he gradually learns to close or inhibit the input of his senses. ... Literate training encourages a heightened awareness of physical boundaries and a sense of those boundaries as the vessel of one's self. To control the boundaries is to possess oneself. ... When an individual appreciates that he alone is responsible for the content and coherence of his person, an influx like eros becomes a concrete personal threat" (1998, 44--45).

Submerged in a highly literate culture as I am, and while writing of the effects of listening, I cannot help but think that sound recording technologies, this new form of writing, makes us re-live the ancient Greek experience, but in reverse. In listening we yet again become acutely aware of boundaries, edges, and their dissolution. Listening awakens Eros, that daemon of the in-between [4]. Infected and overcrowded by sound, with its symbiotic, sometimes erotic and invading energies, we are struck and alarmed by this acute vulnerability.

Deep Listening

What is the pitch of wind? I am sitting in an octagonal water tower, at the very top floor beneath a tin roof. Thin wooden planks separate me from the echoing belly down below, the former water cistern. Following a score by Pauline Olivieros as part of her deep listening practice, I'm trying to reinforce some of the sounds I hear (Olivieros, 1971). My voice finds it difficult to mimic or strengthen the perceived sounds; my body, throat and vocal tract try to form and adjust in various ways to funnel the wind from my lungs, as if I were a dolphin trying to imitate a weird sounding "R." Something similar to throat-singing emerges [5]. I have no sense of time passing. I'm in a resonant spacetime where relations emerge and reveal themselves as a fluctuating whole. I become part of a milieu, a resonance circle, which engages situational, contextual, and participatory sensibilities. I listen, follow, tune in, and participate in a sonic more-than-human commune. I am a membrane, like the tin roof, a sonorous belly, like the cistern. I too am wind. I have not been able to reproduce the weird overtone soundings again, outside of that tower. Somehow, my voice is in the way of sounding.

Aristotle distinguished between voice as mere sound, a cry or moan (phóné), and voice as speech, word, reason (lógos). The latter belonged to political life, to the human realm, the former to bare life reduced to animality. This differentiation between phóné and lógos marks the difference between animal and human in a long tradition of Western thought. Voice as lógos is intimately connected to life in the polis: those who speak intelligibly are included as citizens and granted rights. "They have reached the threshold of humanness," as Lilly put it (1961, 211--212), and only then have they become an ethical problem. In this construct, there is no such thing as nonhuman rights.

In sonorous time, in and through listening, one could be said to perform in concert with the things heard while at the same time being changed by them (Olivieros, 2010). Listening does not only concern the ear but the entire body, it is a mode of bodily interaction and engagement that I find embody what Karen Barad refers to as intra-action (2003, 826). Intra-action does not presume the prior existence of independent entities with inherent characteristics that precede the intra-action. Or as Donna Haraway writes, "Beings do not preexist their relating" (2003, 6). What kind of relatings would I like to be shaped and co-created by, if I had the means to choose?

Figure 6

COLONY

Bonding with Maize

Lately, I have been trying to bond with maize (Holmstedt, 2018; Holmstedt et al, 2019). It might seem odd, as corn is today the world's most cultivated and genetically modified grain. It is one of twelve crops that dominate the global agricultural industry. Twelve crops alone, and five animal species, make up 75% of the total global food production. The genetic diversity inherited from previous generations has decreased drastically since the 1930s. In Mexico for example, 80% of the genetic diversity in maize has disappeared. This means that a massive part of the global food production rests on a very vulnerable genetic base. In my preferred habitat, a newly acquired allotment--which is by the way referred to as a koloni in Swedish, i.e. "colony," I have grown an heirloom variety that has been cultivated by hand from more than 70 different varieties, many of them now extinct, collected from Indigenous peoples and homesteaders across North America.

Lilly's claim in the 1960s that dolphins are intelligent was controversial since animal behaviour was considered mechanistic. Lilly declared though, that it was possible to be intelligent without being human. While animal intelligence is more readily accepted and studied today--though we are still, generally speaking, in the habit of comparing and rating nonhuman animals according to a human-centered notion of both language and intelligence--it remains provocative to ascribe intelligence to nonhuman beings, especially if they are not even included in the animal kingdom. When a group of researchers in 2006 claimed that plants are intelligent and coined the term "plant neurobiology" (Baluska et al, 2006), it was controversial since plant behaviour is considered mechanistic--and, they do not have neurons. Monica Gagliano insists though, that it is possible to be intelligent without having a brain. She has also paved the way for plant bioacoustics and studies of acoustic communication between plants. Extended sound experiments with maize seeds have shown that when exposed to bass sounds for several hours, the germination rate of the seeds is increased. Old seeds start to sprout. In addition, it has been found that maize roots both generate and respond to sound. The roots orient themselves towards frequencies around 220 Hz (Gagliano et al, 2012).

I have to admit that I was tempted to tune in to the frequency of the maize plant and its neuronlike electrical activity. With electrodes, I tried to connect my sensorium with that of the plant in hope of capturing its action potentials--not so dissimilar from Lilly, I realized. Using non-invasive electrodes and lacking the controlled environment of the lab, it is extremely difficult to discern what is being registered. To touch a leaf can trigger an action potential, but what the technical apparatus also captures is a change in electrical conductivity. The plant acts as ground for my electrical charge. I am the cause of the electrical activity, and I do not even have to touch the plant for this effect to occur. What I managed to pick up, turned out to be something akin to galvanic skin response. The same set-up, hooked up to a human instead of a plant, is called a lie detector. Through the electronic set-up, the plant simply becomes a component in a biofeedback system that sonifies and amplifies me. This strikes me as an illustration of what we, despite good intentions, often use animals and plants for.

Figure 7

Meanwhile, in the colony, I notice that this allotted land, with its soil, is transforming me. I no longer think of it as a garden to cultivate or design, but as an ecosystem where I might fit in. Through growing, I become part of a bundle of collaborative systems in a specific habitat. Soils are complex living systems, teeming with microbial life. The soil is a vital part of the plant's metabolism. The soil could be said to be the plant's stomach and intestines. This insight is slowly working its way through me, as a wave in slow motion. How my stomach is like soil, teeming with microbial life, and soils are like stomachs. My perspectives and my body are suddenly turned inside out. I am but a microbe in a stomach of soil. Or, if I look at the kind of functions I perform, digesting plant tissue and offering my urine to the majestic maize, I am actually a kind of earthworm. At least, that's a clan of creatures I strive to belong to, as I have plenty to learn from these ancient transformation masters, soil-makers, and great digestive fermenters. I also notice that I have adapted my being and behaviour according to the needs of the maize plants. Maize could be said to have cultivated and modified me, rather than the other way around. Instead of using sensors and electrodes, I am becoming sensitized. The allotment as interface, or rather, the koloni as a situation of shared surfaces, has over time made me attentive to intricate relations and reverberations across multiple membranes--of colony forming processes, and circumstances under which they might become colonizing.

Among Indigenous peoples, who have cultivated maize for centuries in the Americas, singing and dancing is often part of planting ceremonies. Rather than an exclusively human affair, I understand this to be an expression of interspecies sociality and friendship, as well as of knowledge. Next year, I might sing and dance for my maize-companions. A microbial worm-dance in the stomach of the plants.

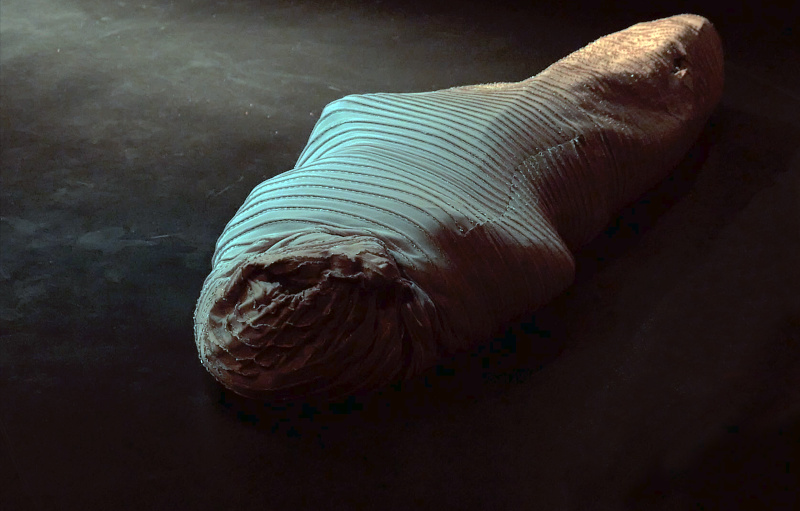

Figure 8

A Worm Session

We prepared our second skins, our membranes (Cederqvist and Holmstedt, 2019). We sewed tubes of fabric, prepared our food and temporary habitat, and for several hours entered a worm-like state. It was hard work and weirdly satisfying--a playful and deeply de-centering experience. We were through bodies, movements and sound drawn into a co-created meaning-making that seemingly could have continued endlessly. I do not pretend that I through this sensory experiment, or act of sensory Verfremdung, know what it is like to be an earthworm, but I am learning something about modes of making common, of becoming sensor (Myers, 2017), as we together try to cultivate more careful ways of knowing.

Worms are hermaphrodites and have neither eyes nor ears, they see and sense through their skin. They breathe through their skin. Contact could be said to be their mode of knowledge. The outer world continuously passes through them as they transform decaying matter into fertile soil. In the process they aerate the earth, and move nutrients and minerals from deeper layers up to the surface. The massive scale of their labor eludes human notice. This is slow and dirty work, invisible regenerative work, body work. These ancient agriculturists represent the generic design for all animal life--a body stretched between mouth and anus. I too am a body stretched between mouth and anus. Digestion, I realize, is a form of reason, of biosemiotics even, through which bodies and worlds mingle.

Into the compositional and decompositional process of our co-created worm sessions, initiated by me and Åsa Cederqvist under the joint name Holi Biont (2020), we bring sound, soil, play, objects, moving images, conversations and storytelling. We choose the relatings we would like to be shaped and co-created by, as an act of resistance, a temporary pocket of air. Play is our reason, the resonance circle where a collective intelligence emerges, together with a sense of belonging. The sessions allow us to invite guests, hold space, and imagine other possible worlds, where we willfully shift frequency range, redistribute desires and experiment with flock-formations and colony-forming processes. The earthworm urges us to take the skin and digestive tract seriously as shared surfaces, as that which connects multiple insides and outsides. We are membranes at work, mucous membranes. Soil, plant and worm work urges me to listen differently, and tune up the sonospheric sensibility of a shared in/side/out. The earthworm also awakens Eros; infected and overcrowded, I try to welcome this acute vulnerability as I continue to follow, be moved, troubled and disturbed, and live the paradox of being neither inside nor outside.

List of figures

Figure 1: Worms and human worms, photo: Åsa Cederqvist, from Coming into Being--a Worm Session #1, and #3 (2019). Drone photo: Lars Siltberg, from Anthropomorphic Interfaces (2019). Water and maize, photos: Janna Holmstedt, from The Blowhole (2016), and A Feeling for the Organism (2018). Cover (detail) of Hardcopy vol. 13, no. 11 (November 1984). Lilly Papers, box 45, folder 8. Courtesy of the Department of Special Collections and University Archives, Stanford University Libraries. B/w photo: Sensory deprivation mask, early version, photo: Ben Ross, in "Experiment in Loneliness," Mechanix Illustrated (May 1962), 56-57, posted May 24, 2006 on Modern Mechanix website, accessed May 12, 2015.

Figure 2: Eisenia fetida, photo: Åsa Cederqvist, from Coming into Being--a Worm Session #1 (2019)

Figure 3: Soundwaves in water, photo: Janna Holmstedt, part of the work The Blowhole (2016)

Figure 4: Sensory deprivation, early version of floatation tank. Photo: Ben Ross, in "Experiment in Loneliness," Mechanix Illustrated (May 1962), 56-57, posted May 24, 2006 on Modern Mechanix website, accessed May 12, 2015.

Figure 5: Human skin, photo: Janna Holmstedt

Figure 6: Dried maize ear, drone photo, and allotment hut, photo: Lars Siltberg, all other photos: Janna Holmstedt, from Anthropomorphic Interfaces (2019).

Figure 7: Maize diary photo: Janna Holmstedt, part of the work A Feeling for the Organism (2018).

Figure 8: Photo: Åsa Cederqvist and Janna Holmstedt, from Coming into Being--a Worm Session #3

Works cited

Baluska, F., Mancuso, S. and Volkmann, D. (2006) Communications in plants. Neuronal aspects of plant life. Berlin Heidelberg New York: Springer.

Barad, K. (2003) Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter. Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 28 (3). 801-31.

Baur, S. (1975) Kneedeep In the Cosmic Overwhelm with Carl Sagan. New York Magazine, September 1.

Carson, A. (1998) Eros the Bittersweet. London: Dalkey Archive Press.

Cederqvist, Å. and Holmstedt, J. (2019) Coming into Being--a Worm Session #3. Fylkingen, Stockholm.

Cederqvist, Å. and Holmstedt, J. (2020) Holi Biont, artistic collaboration [ongoing].

Gagliano, M., Mancuso, S. and Robert, D. (2012) Trends in Plant Science, 17 (6). 323-325.

Haraway, D. (1997) "ModestWitness@SecondMillenium". In ModestWitness@SecondMillennium. FemaleMan©_ Meets_OncoMouse™: Feminism and Technoscience. New York: Routledge. 23--40.

Haraway, D. J. (2003) The Companion Species Manifesto. Dogs, People, and Significant Otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press.

Haraway, D. J. (2008) When Species Meet. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Haraway, D. J. (2013) "Sowing worlds: A seed bag for terraforming with earth others." In Beyond the Cyborg: Adventures with Donna Haraway, eds. Margaret Grebowitz and Helen Merrick, 183-195. New York: Columbia University Press.

Herzing, D. L. (2014) "Profiling Nonhuman Intelligence: An Exercise in Developing Unbiased Tools for Describing Other 'Types' of Intelligence on Earth," Acta Astronautica 94 (2014): 676--680.

Holmstedt, J. (2016) The Blowhole, lecture performance performed in various versions between 2016-2020.

Holmstedt, J. (2018) A Feeling for the Organism, artistic research project [ongoing].

Holmstedt, J., Siltberg, L., and Nilsson, E. (2019) Anthropomorphic Interfaces, artistic research project.

Ihde, D. (2007) Listening and Voice: Phenomenologies of Sound, 2nd ed. Albany: State University of New York Press.

Kontturi, K. (2018) Ways of Following: Art, Materiality, Collaboration. London: Open Humanities Press

LeGuin, U. (1989) "The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction." In Dancing at the Edge of the World. New York: Grove Press.

Lilly, J. C. (1950) A Method of Recording the Moving Electrical Potential Gradients in the Brain: The 25-Channel Bavatron Electro-Iconograms. Conference on Electronic Instrumentation in Nucleonics and Medicine, New York, N.Y., October 31--November 1 and 2, 1949. 37--43. New York: American Institute of Electrical Engineers.

Lilly, J. C. (1961) Man and Dolphin: Adventures of a New Scientific Frontier. Garden City, New York: Doubleday.

Lilly, J. C. (1963) Productive and Creative Research with Man and Dolphin. (Fifth Annual Lasker Lecture, Michael Reese Hospital and Medical Center, Chicago, III., 1962). Arch. Gen. Psychiatry, 8. 111--116.

Lilly, J. C. (1972) The Center of the Cyclone. Looking into Inner Space. Oakland, CA: Ronin Publishing.

Lilly, J. C. (1978) "Appendix Seven." In Communication Between Man and Dolphin: The Possibilities of Talking with Other Species. New York: Crown Publishing Group.

Lilly, J. C. (1997) The Scientist: A Metaphysical Autobiography. 3rd ed. Berkley, CA: Ronin Publishing.

Lilly, J. C. and Lilly, A. (1976) The Dyadic Cyclone: The Autobiography of a Couple. New York: Simon and Schuster.

M0786 (1961). The John C. Lilly Papers, Department of Special Collections and University Archives. Stanford University Libraries, Stanford, California. Box 28, folder 8: [Program] Extraterrestrial Intelligent Life Conference, National Radio Astronomy Observatory, November 1 and 2.

Margulis, L. and Fester, R. eds. (1991) Symbiosis as a Source of Evolutionary Innovation: Speciation and Morphogenesis. Cambridge, Mass: MIT Press.

Myers, N. (2017) "Becoming Sensor in Sentient Worlds: A More- than-natural History of a Black Oak Savannah." In Between Matter and Method: Encounters in Anthropology and Art, eds. Gretchen Bakke and Marina Peterson.London: Blomsbury Academic.

Oliveros, P. (1971). Sonic Meditations. Smith Publications.

Oliveros, P. (2010) "Quantum Listening: From Practice to Theory (to Practice to Practice)." In Sounding the Margins: Collected Writings 1992--2009. Kingston, NY: Deep Listening Publications.

Serres, M. (2009) The Five Senses: A Philosophy of Mingled Bodies, trans. Margaret Sankey and Peter Cowley. London: Continuum. Originally published in French in 1985.

Sloterdijk, P. (2011) Spheres. Vol. 1, Bubbles: Microspherology. Cambridge, MA: Semiotext(e).

Snowdon, C. T. and Teie, D. (2013) "Emotional Communication in Monkeys: Music to Their Ears?" In The Evolution of Emotional Communication: From Sounds in Nonhuman Mammals to Speech and Music in Man, eds. Eckart Altenmüller, Sabine Schmidt, and Elke Zimmermann. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 133--151.

Shapin, S. and Schaffer, S. (1985) Leviathan and the Air-Pump: Hobbes, Boyle, and the Experimental Life. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

Sterne, J. (2012) ed. "Sonic Imaginations." In Sound Studies Reader. London: Routledge.

Tsing, A., Swanson, H., Gan, E. and Budbandt, N. (2017) Arts of Living on a Damaged Planet. Minneapolis, London: University of Minnesota Press.

Ullal-Gupta, S., Vanden Bosch der Nederlanden, C. M., Tichko, P., Lahav, A. and Hannon, E. E. (2013) Linking prenatal experience to the emerging musical mind. Front. Syst. Neurosci. 7(48). doi:10.3389/fnsys.2013.00048

Footnotes

- Lilly later developed a modernized and more sophisticated floatation tank which made use of Epsom salt (magnesium sulfate) in which one could float so easily on one's back that no mask was needed. These floatation tanks were also developed for commercial use in the 1970s and have since then been used primarily for relaxation.

- The term Verfremdung was introduced by German playwright and theatre director Berthold Brecht in the 1930s to denote various techniques through which social and political phenomena could be analyzed and explored in the theatre, Verfremdungeffekt is more commonly known in English as the alienation effect, or estrangement effect.

- Yet, I think Sterne's "litany" does have some bearing on how audiovisual media are commonly used for the purpose of bringing forth certain effects. Thus, this opposition tends to be reproduced.

- In Plato's Symposium, the priestess Diotima situates love as metaxu, "in-between." Eros represents an intermediary, a connecting distance.

- In Mongolian throat-singing, or overtone-singing, one vocalist produces one or several overtones simultaneously over a fundamental pitch. This Tuvan vocal tradition has, I read later, most likely emerged from imitating sounds of the natural surroundings, such as streams and winds. Available from: Smithsonian Folkways Recordings website (1 December 2019).