Understorey: Community Radio and the Nuclear Age

by ADRIAN GLAMORGAN and ELIZABETH PO'

- View Adrian Glamorgan's Biography

Adrian Glamorgan is a community radio journalists based in Perth.

- View Elizabeth PO's Biography

Elizabeth PO' is a community radio journalists based in Perth.

Understorey: Community Radio and the Nuclear Age

Adrian Glamorgan and Elizabeth PO'

Introduction: broadcasting voices

Understorey is a weekly environment community radio program, evoking the view from below, celebrating ecology, while also examining the multiple environmental crises around us.1 Our starting place is in the heart of one of the world's biodiversity hotspots, the South West province of Western Australia (WA), original and continuing home of the Noongar people. This region might describe the limits of our FM broadcast but our ecological fascination extends to state wide and international concerns about the causes and consequence of climate change, loss of biodiversity, declining water and air quality, urban congestion, loss of arable land and fisheries, gyres of waste on land and sea, and nuclear threats.

As volunteer radio feature/documentary makers, our pre-produced programs vary in capacity and artistry: sometimes as a single interview if limited time or subject matter suits; although when possible we prefer to edit with several voices and soundscape to create layering, with several perspectives that reflect the many voices and stakeholders, and to explore the creativity of radio documentary as an art form.

Figure 1. Understorey promotion for 'Beyond Nuclear War and Radioactive Peace'

Radio is a medium of long distance, a mass communication blowing silent in the wind, and yet sometimes a wonderfully intimate space.2 Mia Lindgren reminds us that "Radio and audio forms have long privileged the human voice and the emotions of living" (Lindgren 2015, 11). These shared stories, told so intimately, can reveal the 'other' and transcend polarized thinking. The well-told story finds a space and claims time in an information-noisy world to both go inward and connect outward.

Because of this mood of intimacy, and the richness of stories that can be told, radio documentaries (and their cousins podcasts, and audio found on blogs and websites) are experiencing a listening renaissance. Audiences appear to enjoy programs weighted in favour of first person stories rather than 'aural aesthetic' or 'radio film' arts experiences pioneered in Australia in the 1970s (Lindgren and McHugh 2013, 106). This American Life (Glass, 1995) has been widely influential, strengthening the mix between narrator; the actuality; and backing music (to set the mood, create continuities, and indicate speakers). Community radio documentaries made in Australia cannot draw on the same level of resources, but even with a week's production turnaround, a good story goes a long way.

Understorey episodes are requested for rebroadcasting by other radio stations across Australia, and each episode is available for re-streaming from the web, providing a public record locally, and a resource for niche global audiences and communities of interest. We imagine our audience as informed and active citizens -- listeners seeking more than the public policy analysis provided by the local 'mainstream' media, including underfunded local public broadcasters. But a specialist audience also exists inside the corporate and political world: those who read media monitoring reports and therefore may realise their decisions are being scrutinised. We have been told that news of our broadcast (if not a transcript) sometimes finds its way to influential offices and strategic desks, encouraging belief that community radio has a role within the fourth estate to scrutinise the executive, and press for greater corporate social and environmental responsibility.

Nuclear stories blowing in the wind

Perth may seem like a remote city, yet our 'local' nuclear narratives challenge what constitutes 'community' in our radio practice. WA experienced the first ever British Empire nuclear weapon, detonated at Monte Beloo Islands in 1952; and Understorey interviewed a Monte Bello veteran recalling his 'shorts and sandals' exposure to the initial atomic bomb test, and describing how his skin cancers are regularly removed each month (Glamorgan and PO' 2103). Aboriginal people have recounted to us atomic bombs detonating near their own desert communities in South Australia at Emu Field and Maralinga, with stories of chance radioactive encounters and forced evacuations -- in some cases bringing their families to WA, only to find themselves living close to uranium deposits. Despite safety concerns and a lack of profitable economic modelling, a conservative WA state government expressed eagerness in 2008 to develop the nuclear industry, and lifted the state's ban on uranium mining (Clarke 2008). For Understorey we researched proposals that would leave uranium tailings on dry salt lakes, despite the dangers from the next flash flood; we have covered erratic environmental protection decisions; and governments and corporates apparently brushing off safety concerns and Aboriginal protests. Which corporation could faithfully manage intermediate nuclear waste repositories for millennia to come? Another program considered radioactive rare earth minerals being shipped to Malaysia, linking us beyond our shores. Then a Class 7 nuclear disaster at Dai Ichi reactor in Japan, fuelled by Australian uranium, showed Australian trade could poison country far away. A Japanese Buddhist pilgrim to WA via Fukushima, Hiroshima and Nagasaki, participated in a reconnection with land and Aboriginal country in the northern Goldfields known as the Walkatjurra Walkabout (2017), and told us she us she was protesting uranium mining in WA because here was "the beginning of the nightmare."

1) from Understorey 20130515, 1'57", Beginning of the Nightmare.

In our small, volunteer, two-person enterprise, we seem to bump into nuclear stories, finding that radioactive entanglements -- like the streams of radiation blown around the world since 1945 -- are both here, there and everywhere. Our own family histories suddenly emerge, remembering a Nuclear Age that others too might discover in their own lives -- for one of us, a mother who grew up in the 1920s near a large uranium deposit in the desert, the same place local Aboriginal people still call sickness country. By co-incidence, Elizabeth's cousin's husband remembers his own father's stories about being a POW in Nagasaki, the day the second atomic bomb dropped. The cousin's father, journalist Norman Milne, managed to witness and report the first Monte Bello Islands test.3 Then for Adrian: his son's maternal great grandfather went over east as a civilian carpenter, it seems possibly to Emu Field, coming back to Perth irreparably damaged by some secret accident, spending the remainder of his life incapable, and sometimes curiously playing by repeatedly knocking down toy soldiers blasted along a trench. Around that same year, half a world away, Adrian's father marched on parade in Bermuda (Stevens 2014, 135), guarding Churchill and Eisenhower, whom we now know were earnestly discussing in this 1953 meeting whether to use nuclear weapons on China (Boler 2003). In 1957, Adrian avoided being tested in the womb with medical radionuclides at Swansea Hospital, in Wales, only to be subjected a few days later to the winds blowing from a secret accident at Windscale (now Sellafield), which sent high levels of radiation across the local valleys (Penny et al. 2017). When five, in October 1962, Adrian's father left for work, kissed his mother goodbye, both of them dreading it was for the last time, anticipating the Cuban Missile Crisis could end the world before the end of my father's factory shift. The sub-atomic realm has powerfully shaped global geopolitics in this nuclear age, but its impact on affected populations in these small biographical ways remains to be systematically examined.

2) from Understorey 20131204, 3'56", Nancy Milne

Beyond such surprising discoveries, we had other chance encounters -- including a university chaplain in Fremantle, who happens to be an American from Hanford -- the place where the Nagasaki plutonium bomb was constructed, and whose school basketball team sports the mushroom cloud logo (Glamorgan and PO', 2014). We also met someone at a wedding, who was planning an early Walkatjurra Walkabout in solidarity with traditional owners from Yeelirrie.4 Another friend recalled an earlier time outside NATO headquarters in Brussels, trying to stop Europe being laid waste by tactical nukes; meanwhile we encountered two friends who each separately turned out to be brave adventurers sailing the Pacific to defy the French at Mururoa; also an expert on failed uranium waste dumps, whom we met at a conference; and the local Red Cross, applying their international humanitarian law mandate to oppose nuclear weapons in Perth.

3) from Understorey 20150826, 1'36", Max Kimber.

Making Good the Fourth Estate

In 2015 The Bulletin of Atomic Scientists' Doomsday Clock updated their decades' old warning, moving the symbolic minute hand significantly forward, to three minutes before midnight. The alert about the threat to human civilisation was worth a paragraph or two, for a news cycle or two. In early 2017, when the Doomsday hand was brought to two and a half minutes to midnight, media response remained minimal, until some time after the US presidential inauguration. The flare-up and sudden escalation by mid-2017 of North Korea and an unpredictable new American president brought nuclear weapons suddenly back onto main stage, and front page. As matters worsened, this attention was obviously merited, but media gaze fixated towards the Korean peninsula. This was American foreign policy, not nuclear anxiety alone. Millions dying in Pyongyang or San Francisco would be an unprecedented tragedy; but surely warnings that hundreds of millions could die across the globe because of a South Asian nuclear conflict precipitating a global nuclear winter (Toon et al. 2007), should be of equal or even greater ongoing media concern? Apparently not. In early 2018 the Doomsday Clock was moved to two minutes to midnight (Bulletin of Atomic Scientists 2018).

Media's ongoing focus on perceived military enemies, who are judged to be the wrong hands too near the button, rather than questioning the existence of any button connected to mass slaughter, is a form of War Journalism that does not serve the democratic process (Galtung 2013, Lynch and McGoldrick 2005). The public does not maintain a consciousness about the global network of legacy mishaps from plutonium-spoiled islands and deserts and experiments (de Brum 2015); hears too late about nuclear missile accidents in buried silos (Schlosser 2013); and is heavily informed about the threat of America's enemies proliferating; but sits in media's strategic silence about Israel's illegal possession of nuclear weapons. The earliest diplomatic anxiety is broadcast when Iran or North Korea threaten imitation. While North Korea is understandably condemned and sanctioned for nuclear acquisition, the Australian government and mainstream media alike draws scant alarm about the dangerous tensions and unstable relations between nuclearised Pakistan and India -- even though these trouble spots appear to present a far greater ongoing risk to global environmental and public health safety through nuclear winter (Toon et al. 2007; International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War 2017). Soothing metaphors of 'nuclear umbrella' and 'extended nuclear deterrence' go unchallenged, despite not appearing in any treaty or promise between the United States and Australia.

The crisis in the media business model only partly explains this reporting neglect. The South Asian threat existed when classifieds still sold newspapers. The rise of the security state is a psychological frame which also might shape fourth estate neglect. A major nuclear power plant disaster, and the proximity of a perceived nuclear threat, also presents challenges for press freedom (Kingston 2017). If this is so, then under-resourced, volunteer-based, community radio, can play a part in making good the fourth estate.

Alternative media needs to include but cast beyond its own 'usual suspects' and 'serendipitous encounters': to seek out more inclusive conversations with corporate and government officials that otherwise go unreported. When yellowcake sales to the United Arab Republic and India were being promoted by WA politicians and mining CEOs, Understorey reminded listeners that Australian uranium fuelled the disastrous Fukushima nuclear plant, challenging ongoing assurances of the efficacy of 'international safeguards.' The radio station's website, archiving past programs, also helps salvage such a 'buried' national story.5 Officials may ignore or decline the invitation, (just as regularly as Australia's Foreign Minister, Western Australian MP Julie Bishop, has done,) and the requests themselves remind these public figures of assertive civil society, and their civic duties and responsibilities to serve, to be transparent and accountable.

In this way community radio contributes to strengthening the Fourth Estate. For example, when alternative radio is streamed on the web, Fukushima listeners no longer need be baffled by the World Health Organisation's early role in March 2011 as it played down Fukushima's radioactive public health risk. If mainstream media has to 'localise' -- atomise -- news to make it entertaining, a community radio can 'ecologise', request interviews from officials from international agencies -- such as WHO in Geneva, and IAEA in Vienna -- to connect the citizen with the largely invisible frameworks that shape our human experience.

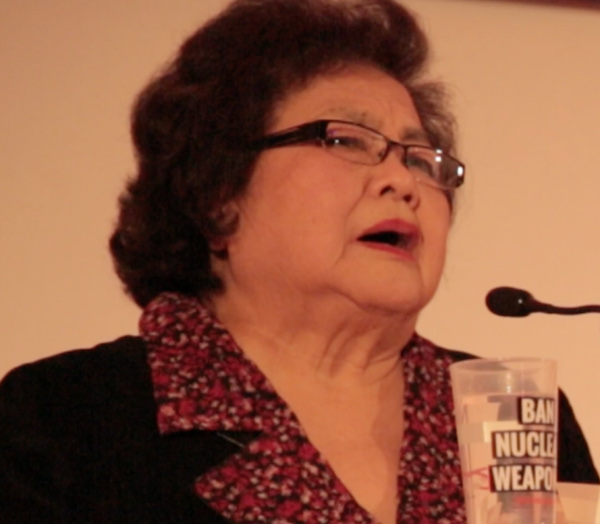

Figure 2. Hiroshima atomic survivor Junko Morimoto addresses a rally in Western Australia, to celebrate the 2014 Fremantle Declaration, co-sponsored by Mayors for Peace and the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN).

Understorey has featured several interviews with mayors involved in building cultures of peace, and opposing nuclear weapons, from all around the world.

The focus of peace journalism also challenges community radio's own limits on volunteer custom and practice. In 2013 we decided to self-fund a radio-interview trip to Fukushima, Hiroshima and Nagasaki.6 We wanted to bring back stories that the big networks in Australia and the United States disregard, and we met nuclear survivors (hibakusha), community health workers, children's advocates, peace campaigners and organizations including Peace Boat, Mayors for Peace, Women's International League for Peace and Freedom, International Physicians for the Prevention of War, and the International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons. Inspired by all these people, we became much more mindful of global stirrings to abolish nuclear weapons, crafting interviews into programs we could broadcast 'locally' in a series we called Beyond Nuclear War and Radioactive Peace.7

5) from Understorey 20131106, 1'05", Fukushima Alarm

6) from Understorey 20131120, 35", Hiromi Kurosaka Fukushima

7) from Understorey 20131113, 1'30", Kenichi Hasegawa Fukushima farmer

8) from Understorey 20131113, 4'33", Koriyama

Setsuko is counting on us

"I am counting on you," says Setsuko Thurlow. Her voice is a determined, unshakeable plea to the assembly of diplomats, scientists, civil society, and media who have gathered in the Hofburg Palace, Vienna. It is three weeks before Christmas 2014, and 150 nations of the world have sent their representatives.8 Aged in her eighties, Setsuko is calling for swift action to end the era of nuclear weapons, within her lifetime. As a survivor of an atomic bomb attack - widely known by the Japanese term hibakusha -- Setsuko carries a rare and magnetic moral authority to speak.

Hibakusha often begin their stories from the ordinary, setting a benign scene preceding unimaginable horror. As a thirteen-year-old schoolgirl, on August 6th, 1945, Setsuko begins her very first day doing war mobilization work. The sky is blue. It is summer. There is a plane in the sky. An atomic flash comes from outside Setsuko's second floor office window. The ferocity of the blast throws her around the collapsing building, leaving her pinned beneath the rubble, bewildered and feeling she may soon die. Rescuers arrive, and give Setsuko back her life. She stumbles outside, but her old world, as well as yours and mine, is torn catastrophically asunder.

Another survivor stands bewildered, another is collapsed, but most have died or disappeared, incinerated. Everything depended on a random position in space-time, that one fulcrum moment, deciding life, or sudden annihilation. Yours and my picture of stable existence is vaporised by the instantaneous, inhumane, blinding, radiating death, killing, demolishing, deafening, battering, dissolving, searing. A whole city gone. Fires burning in all directions. Humans turned to ghosts. Flesh torn from civilians, organs exposed, bewildered, helpless. There is no help. In a nuclear attack, the city's doctors and nurses are mostly killed, or burned, or irradiated too. Hospitals are mostly demolished, too. There is everywhere confusion.

Setsuko wanders in the Boschian nightmare that transforms Hiroshima, 6 August 1945. To stagger amongst the desecrated living, the city turned to trashed bricks and irradiated soot, those with the unquenchable thirst, the filthy black rain, this is the worst day, the first, of a hazardous existence dictating what is left of a life.

Figure 3 Setsuko Thurlow addresses the Vienna ICAN Conference. Photo by Adiran Glamorgan.

9) from Understorey 20150805, 3'57", Setsuko Thurlow testimony from Vienna

The hibakusha stories do not end on August 6^th,^ 1945. At Nagasaki on August 9th the dead are too many to count, school after school, emptied of students. Mutterings about war crimes get louder.9 The United Nations' first resolution hopes for nuclear disarmament, but meanwhile 'remote' testing locations are sought out and identified by those nations seeking prestige, power, or a salve to their proliferating fears. A nine-year-old fishing with his father in the northern Marshall Islands sees everything turned red, from the 1954 Bravo shot at Bikini Atoll, two hundred miles away. Between 1946 and 1958 the Marshall Islanders receive an equivalent of 1.6 Hiroshima shots per day, for twelve years (De Brum 2015). The women give birth to "jellyfish- and monster-like bodies" and there are cancers (Anjain-Maddison 2014, 34). In the Monte Bellos, soon after the first British test, Royal Australian Navy sailors land at ground zero to inspect the debris, receiving undisclosed doses of radiation (Glamorgan and PO' 2013). In Emu Fields and Maralinga, service personnel are exposed; and Aboriginal people dispossessed, or physically hurt, just as with any other hibakusha in the testing era. GIs stand up in Nevada, and watch the mushroom cloud rise high into the sky, while they are surreptitiously monitored by doctors for ill effects. Housewives in St George, Utah are reassured by governments, but oncologists proliferate: as survivor Michelle Thomas tells Understorey, the nuclear weapons were being used by the government against their own people. (Glamorgan and PO' 2016).

10) from Understorey 20150826, 4'01", Sue Coleman Haseldine and Tillman Ruff

Meanwhile, on the other side of the irradiated Iron Curtain, villagers in Kazakhstan are summarily evacuated: while ten folk left behind are given vodka by the Soviet military officers 'to protect them from the radiation'. Close to these sites 'jellyfish babies' are born; families feel pain, horror and shame, and only some children are sent to school. (Glamorgan and PO' 2015).

Figure 4. Karipbek Kuyukov, Kazakhstan nuclear test survivor born in 1968 (right) and translator (left) at the Hofburg Palace, Vienna. We interviewed Karipbek and other nuclear survivors for Understorey at the 2014 Vienna meeting of the open ended working group on the humanitarian impacts of nuclear weapons, a key step towards the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.

Those avoiding the bitter, staggering death from radiation in the first few days, months and years, are still prone to relentless maladies. The war finished, but surviving hibakusha contend with aftereffects on their wellbeing, fertility, longevity, and the frustrations of official silence. Meanwhile a disrupted DNA might betray a beloved child. If descendants are born, they might carry the irradiated changed genes, damaged by that single atomic weapon, those fateful microseconds, split gene segments borne downward into untold future generations. Nuclear weapons are genocidal, travelling through the DNA of subsequent generations. With the mystique comes the social exclusion. Mere mention of a city of origin could end the prospect of any suitor. For many Japanese hibakusha, the shame, disgrace and social isolation of being a nuclear survivor can last for decades. Then around 70, something stronger seems to take hold: In gratitude for a long life (albeit often affected by cancers and unusual illnesses, dizziness, poor immunity, or a mosaic of unusual maladies) some survivors contemplate the meaning of the grace of survival, and they end a long silence. They now call for decisive action: the global banning of nuclear weapons.

11) from Understorey 20151007, 4'54", Karipbek Kuyukov in Vienna

Understorey's interviews with nuclear survivors explore and promote a shared future -- to first understand how capable we all are of planning, making, and using nuclear weapons while facing their consequences, and then identifying opportunities for humanity's emancipation from their threat. However, as hibakusha recount the nightmare, how many details should the peace journalist pass on? Each hibakusha may have recounted experiences many times, perhaps at personal cost. In our 2017 program 'Avoiding Hiroshima', hibakusha Miyake Nobuo acknowledged that he sometimes withheld material; and that his own brain blotted out several hours of grotesque experiences of that terrible day (Glamorgan and PO' 2017). When it came to broadcasting some of the graphic testimony shared by second generation hibakusha Mariko Higashino we baulked: quite apart from community radio broadcast prohibitions on difficult material, how much of the details do our audience need to know? Mariko's mother searched for Mariko's grandmother, finding her five days after the bomb, just before she died: eye exploded and dangling out, one side of her body burned to charcoal, her family member longing for water and comfort. Do we broadcast such terror? How many times? Is their greater dignity in our telling or not telling? Can we afford the ignorant to underestimate the atrocity of a crime against humanity?

12) from Understorey 20170809, 5'58", Miyake Nobuo Hibakusha Hiroshima

As Setsuko Thurlow told the Physicians for Global Survival in 2003: "I have to brace myself to confront my memories of Hiroshima. It is exceedingly painful to do this because I am overwhelmed by my memories of grotesque and massive destruction and death" Setsuko warns: "My message could be painful to you as well, as I intend to be as open and honest as possible in sharing my experience and perceptions." (Thurlow 2016). How should a journalist respond? Mia Lindgren recommends Harrington's 'hybrid ethical outlook' which, similar to an anthropologist, protects and honours the interviewee's "dignity and privacy" (2015, 12). There may be no final resting place on this matter, only a sensitivity and ethic, which a community radio station, any media outlet really, and certainly every journalist, should consider carefully.

Journalism and the Nuclear Weapons Ban Treaty

Beyond this is the larger story, the one the hibakusha wish to challenge: the humanitarian consequences that the nuclear states prefer us to forget. Australia's national defence policy supports "extended nuclear deterrence" or END: a supposedly protective theory of mutual menace that has Australia participating in a threat to inflict nuclear war on cities. As we write, many nuclear weapons around the world are on high alert, ready to do this very deed. There have been too many past miscalculations, 'normal accidents' (Perrow 1999) to suggest our global luck will last indefinitely. Hibakusha, and the International Red Cross and Red Crescent movement, assure the world that no meaningful humanitarian response would be possible. Disregarding these concerns, nuclear states argue nuclear governance established by the 1970 Non-Proliferation Treaty is sufficient for the time being, but this has failed to convince a number of significant Cold War 'hawks' who have faced the realities of the nuclear threat. Since 2007 former Secretaries of State George P. Schultz, Henry Kissinger and Colin Powell, as well as former Secretary of Defence William Perry, and former senator Sam Nunn, have campaigned for the elimination of nuclear weapons (Taubman 2012).

13) from Understorey 20141001, 5'12", Red Cross IHL Yvette Zegehagen

Australia's role in preparing for variations of World War III, through 'joint' facilities such as at Pine Gap near Alice Springs, highlights our preparedness, in certain conditions, to play an essential role in killing these millions of innocent civilians in China or Russia. Since natural justice and moral repugnance might cause us to baulk, collective amnesia is a necessary step in preparations for war: lest we remember the humanity of others, and regret our commitment threatens actual genocide and crimes against humanity.

With his journalist's eye for detecting cant and deception, George Orwell identified the role of doublethink in preparations for war (Orwell 1949). There is a little of Nineteen Eighty Four in nuclear states, and supportive allies, encouraging amongst their citizens a numb business-as-usual normality, assuming an absence of terror and risk, so that civilian populations may shrug off the horror, deny any military immediacy, attend to the ordinary, and wave through preparations for genocide. Survivor accounts like Setsuko's expose, in all their horrific particularity, the barbarous outrage of the real consequences of indiscriminate nuclear mass warfare. A journalism that values remembering consequences of war, can awaken citizens and leadership from self-deception.

The assembly at the Hofburg Palace in 2014 included 127 countries who, within six months, formally endorsed the Austrian 'humanitarian pledge'10 to provide an approach to energise the nuclear possessor states' commitment to work towards disarmament already outlined in Article 6 of Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. But in 2014, in that rococo palace made famous by Metternich, the United States and its ally Australia expressed hope for nuclear disarmament -- but not until some indeterminate time in the future, when there will be more willing partners and conducive conditions.11 Australia was keen for a new treaty to be "inclusive,"12 that is, to maintain the primacy of the nuclear powers granted by the Non-Proliferation Treaty.

On 7 July 2017, a majority of United Nations member states in conference adopted the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons (UN News Centre 2017). By March 2018 all of 57 countries had signed the treaty, and seven ratified. Despite nuclear states' expressed willingness in certain extreme conditions to use nuclear weapons on each other, they eerily remain united, in fierce agreement, that a treaty to ban nuclear weapons is no way to disarm the world. The treaty now needs 50 ratifications to become international law.

Australia's opposition to this process of disarmament still does not attract much domestic media. North Korea certainly does. In that context, Australian and Japanese foreign ministers speak of the 'nuclear umbrella' as if it is a substantive thing, rather than a metaphor or expectation vindicated by game theory, a certainty based on a bet. In the case of Australia, there is no treaty protection. Article Three of the ANZUS Treaty is no more than a promise to consult, and if the hope of mutual aid means an agreement to kill millions of civilians in counterstriking an attacker, should the instance arise, it is a debate in which civil society has yet to be fully entrusted or included. Yet Johan Galtung's "peace journalism," encourages us to openly interview the diplomat defending extended nuclear deterrence, and critically analyse the methods of anti-nuclear activist hoping for unilateral disarmament. This is not a matter of polarities, but of building conversations, and possibilities (Galtung 2003; Lynch and McGoldrick 2005; Youngblood 2017).

By 2014, the Doomsday Clock had been reset many times, civil society had organised, and many middle powers had convened three major conferences to abolish nuclear weapons, yet the treaty debate did not merit much 'national' reporting inside Australia. At the Vienna conference itself the American media was entirely absent, save one reporter funded by a progressive evangelical group. The mainstream media and thus the wider world did not witness in the Hofburg Palace the majority of UN member states' recoil in palpable anger at the United States' attempt to unbalance the process. In another palatial room, an Australian radio station interviewed Sue Coleman-Haseldine and the head of the Red Cross in Australia Robert Tickner by phone. The attendant Australian ambassador could not speak to us on the record, for reasons of protocol. Back at home the (local, Western Australian) Foreign Minister of Australia regularly declined to speak with us, for reasons not given. If the debate doesn't get covered in the media of public record, perhaps it never happened.

"As a tool to think": Peace journalism and the search for solutions

If investigative journalists aspire to expose wrongdoers, we aspire instead to be peace journalists (Galtung 2013).13 Our business cards subtitle us as "journalists seeking solutions". Our program foregrounds the voices of researchers, writers, citizen scientists, environmental campaigners and public policy advocates who are often ignored or underreported by mainstream media. We also recognize the need to seek out those in power -- people surprisingly often not sufficiently scrutinized -- to bring their account of policy, understand their perspectives, re-evaluate listeners' own projected stereotypes. That may mean we give a Minister of Mines a full program to explain about allowing uranium mining, or to an interview with management at Japanese company TEPCO about systems failure at Fukushima. The aim is to reveal and share, not score points; to identify where progress might be made, to imagine conversations between stakeholders. We hope that radio with its practices that favour shared listening and insight might engender conversation, understanding, and even transformation.

Figure 5. Recording a meeting at Hiroshima. Maralinga Tjarutja delegates, other Australian peace workers and Hibakusha representatives. April 2016. Photo by Jessie Boylan from the Nuclear Futures Partnership Initiative.

In his book Hiroshima, a 30,000-word account of six atomic bomb survivors, John Hersey first opened the average American eyes to the reality of the savagery of the weapon (1946). It was published in its entirety (without cartoons, or reviews) in a single issue of The New Yorker. Not only did the edition sell out immediately, but the Book of the Month club distributed it free to members, and syndication and reprints followed. Radio in particular played a particularly vital role in reaching Americans "across socio-economic groups" (Forde 2011, 569). The US ABC radio network broadcast the entire text over four half-hours (incidentally winning the George Foster Peabody Award for the Outstanding Educational Program of 1946), thus generating a high peak of discussion both in the media and the community. With nearly all American households with radios, on air discussions by popular radio personalities were able to use Hersey's Hiroshima as "a tool with which to think":

They used it in various ways: to reify the role of American journalism and media in shaping social thought and national identity (by praising the editorial courage of the New Yorker and the report's contribution to knowledge); to consider the ethical implications of atomic bombs; to discuss the problem of a likely atomic arms race; to champion the idea of world government; and to make passionate calls to American citizens to join forces in demanding national political action to control atomic power in the world. (Forde 2011, 570).

These themes have hardly disappeared in the decades since 1946, but changes to the media business model, and technological fragmentation of news distribution, makes the chance of 'mainstream' media touching on such issues highly dependent on, and vulnerable to, passing current events, and even then, as suggested, confined within the dynamics of a debate about "normality" practiced as journalism. The journalist as peace advocate does well to consider an inner journey too. In the 1980s, many anti-nuclear activists knew, by warhead, how many millions of people would die if a confrontation occurred. This kind of intimacy with mega-deaths can be personally, physically, mentally and spiritually exhausting. With our own limited volunteer resources, we occasionally hold experiential workshops, working with the stories; and although humble in reach, we wonder if we they could be reminiscent of popular engagement arising from John Hersey's New Yorker article in 1946 -- by inviting participants to interact within an 'open circle' to strengthen individual and community resilience. Such folk became dependable experts, and yet would often suddenly withdraw from activism altogether.14 Many activists undertook Joanna Macy's Buddhist-informed "despair and empowerment process" that suggests these feelings must be acknowledged, felt, and then decisively foregone; although the vulnerability and self-discipline of such a practice will reliably revitalize efforts (Macy 1983). Activists found it beneficial to identify and reconcile with their own "inner Trident" that channeled inner violence through the guise of social change. Self-awareness became an essential practice then, as it might be now for the journalist reporting nuclear events.

Conclusion

While Understorey covers a range of local environmental stories, we have also followed the intersecting trails of nuclear narratives, discovering a worldwide community engaged in action. Making programs for Understorey over the years has shown us that the nuclear narrative beats many paths criss-crossing the globe, connecting the local to the cataclysm. We have also worked with the potential of radio documentary and community radio within a reconstituted local/international fourth estate to foster remembering and produce listening and insight, to encourage critical understanding, and promote courage. We have had the privilege of meeting with remarkable people in Australia and globally, people who carry nuclear narratives in their hearts, minds, and sometimes even their own radioactively damaged DNA, people whose words and images might yet change the world.

Peace -and solutions- journalism faces grim details, bravely offered by hibakusha and others, then facilitates storytelling evoking the best qualities of human beings: people's courage, dignity, and love for each other and the environment. Whether civilian, nuclear veteran, or Indigenous, the richness of their stories contrasts and energises the humanitarian perspective, and we learned the value of hearing stories being shared by voices worst affected by the Nuclear Age, survivors who have witnessed at close hand the ferocity of a chain-reaction hotter than the surface of the Sun. But the soulless profits of the corporations cannot distract the nuclear peace journalist from the humanity of the weapons manufacturer, or the deepest aspirations of the diplomat. Each of us plays an innate inescapable role in humanity's stepping back from destruction. To tell the nuclear story we need to play a long game, and also one that attends to connecting us, person by person by person across a globe of self-discovery, towards peace with the other today.

Works Cited

Anjain-Maddison, Abacca. 2014. 'Human consequences: testimonials on the health, environmental, socio-economic and cultural impact of nuclear tests.' in Federal Ministry for Europe, Integration and Foreign Affairs, Republic of Austria. *Vienna Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons Conference Report. *

Australia's statement at the Vienna Conference, 2014. Web. Accessed on 22 May 2017.

Boler, David. 2003. 'Bermuda: Model for Summits to Come.' Finest Hour, 119. Web. Accessed 21 May 2017

Bulletin of Atomic Scientists. 2018. Doomsday Clock. Web. Accessed on 21 April 2018.

Clarke, Tim. 2008. 'Barnett lifts WA uranium ban.' Watoday. 17 Nov. Web. Accessed 4 June 2017.

De Brum, Tony. 2015. Statement of Marshall Islands to the 2015 Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty Review Conference. Web. Accessed 27 April 2015.

Department of Foreign Affairs. 2013. Australian Government's stance on nuclear weaponry. Web. Accessed 27 April 2015.

Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade File 15/2850. 2015. in Conference on the Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons 8-9 Dec [2014]. Web, Accessed 29 June 2017.

Forde, Kathy Roberts. 2011. 'Profit and public interest: A publication history of John Hersey's 'Hiroshima'.' Journalism and Mass Communication Quarterly. 88(3), 562-579.

Glamorgan, Adrian and Elizabeth PO'. 2013. 'Shorts and Sandals Nuclear Policy', Understorey. First broadcast on RTRFM 92.1 on 4 Decembee. Web Web. Accessed 4 June 2017.

Glamorgan, Adrian and Elizabeth PO'. 2014. 'Generations of Nagasaki'. Understorey. First broadcast on RTRFM 92.1 on 7 September. Web Accessed 4 June 2017.

Glamorgan, Adrian and Elizabeth PO'. 2015. 'Arms across the Earth'. Understorey . 2015. First broadcast on RTRFM 92.1 on 7 October.

Glamorgan, Adrian and Elizabeth PO'. 2016. 'Downwinders', Understorey. First broadcast on RTRFM 92.1 on 27 April.

Glamorgan, Adrian and Elizabeth PO'. 2017. 'Avoiding Hiroshima', Understorey. First broadcast on RTRFM 92.1 on 9 August.

Galtung, Johan. 2013. 'Peace journalism.' Media Asia. 30 (3), 177-180.

Glass, Ira. host. 1995. This American Life. Chicago Public Media.

Hersey, John. 1946. Hiroshima. Nicholls.

International Physicians for the Prevention of Nuclear War. 2017. Nuclear famine: climate effects of a nuclear war. Web. Accessed 30 June.

Joint Standing Committee on Treaties. 2011. Official Committee Hansard. 31 October.

Kingston, Jeff, ed. 2017. Press Freedom in Contemporary Japan. Routledge.

Large, John H. 2005. Development of nuclear weapons technology in the area of North East Asia (Korean peninsular and Japan). Ref R3126-A1. Greenpeace International.

Lindgren, Mia and, Siobhan McHugh. 2013. 'Not dead yet: emerging trends in radio documentary forms in Australia and the US.' Australian Journalist Review, 35(2). 101-113.

Lindgren, Mia. 2015. 'Balancing personal trauma, storytelling and journalistic ethics: a critical analysis of Kirsti Melville's 'The Storm''. RadioDocReview, 2(2). Accessed 4 June 2017. ro.uow.edu.au/rdr/vol2/iss2/8.

Linnane, Richard. 2014. Statement on Australia's position at the Vienna conference.PDF. Accessed on 22 May 2017.

Lynch, Jake and Annabel McGoldrick. 2005. Peace journalism. Hawthorn.

Macy, Joanna. 1983. Despair and personal power in the nuclear age. New Society.

Orwell, George. 1949. Nineteen Eighty-Four. Secker and Warburg.

Penny, W., B. Schonland, J. Kay, J. Diamond, J and D.E.H. Peirson. 2017. Report on the accident at Windscale No.1 Pile on 10 October 1957. Journal of Radiological Protection, 37(3).

Perrow, Charles. 1999. Normal Accidents: Living with High-Risk Technologies. Princeton.

Scheinman, Adam. 2014. Statement to Vienna Humanitarian Impact of Nuclear Weapons Conference: Impact of Nuclear Weapons Explosions. Web

Schlosser, Eric. 2013. Command and Control. Penguin.

Stevens, Tom. 2014. A Welch Calypso: A soldier of the Royal Welch Fusiliers in the West Indies, 1951-54. Helion.

Taubman, Philip. 2012. The Partnership: Five Cold War warriors and their quest to ban The Bomb. Harper.

Taylor, Arch. B. 2005. Pearl Harbor, Hiroshima and Beyond: Subversion of values. Revd. Ed. Trafford.

Thurlow, Setsuko. 2016. 'Meet Setsuko Thurlow'. in Hibakusha Stories. Web Accessed 23 September 2016.

Toon, Owen B. , Alan Robock, Richard P. Turco, Charles Bardeen, Luke Oman and Georgiy L. Stenchikov. 2007. 'Consequences of regional-scale nuclear conflicts.' Science, 315. 5816. 1224-5.

Transcend Media Service. 2017. Galtung's Principles for Peace Journalism. Web. Accessed 30 June 2017.

UN News Centre. 2017. UN Conference adopts treaty banning nuclear weapons. 7 July. Web.

UNESCO. 2012. Quotes on radio. Web. Accessed 4 October 2016.

United Nations Generally Assembly. 2012. Resolution 67/56.

Walkabout Walkatjura. 2017. Web Accessed 4 June 2017.

Youngblood, Steve. 2017. Peace journalism principles and practices: Responsibly reporting conflicts, reconciliation, and solutions. Routledge.

Footnotes

- Our radio station is RTR FM 92.1. For a backlist and restreaming of Understorey programs, go to https://rtrfm.com.au/blog/category/Understorey/. We also work under the name 'Yanwaves', and our email contact is yarnwaves(AT)gmail.com. ↩

- Marshall McLuhan said, "Radio affects most intimately, person-to-person, offering a world of unspoken communication between writer-speaker and the listener." (in UNESCO 2016). ↩

- Norman Milne won the 1952 Lovekin Prize for Journalism in 1952 for the best news story of the year in Western Australia for "WA Island Site for Atomic Test." ↩

- Now an annual pilgrimage/celebration of Wangkatja country "to reconnect people with land and country." See https://walkingforcountry.com/walkatjurra-walkabout/ ↩

- See coverage by the Joint Standing Committee on Treaties. Official Committee Hansard. 31 October 2011. p.9. ↩

- We also made the trip in our role as civil society support for Mayors for Peace in Australia, which provided us a means to interview mayors working for peace. ↩

- This series was finalist for a United Nations Association of Australia Environment Reporting Award in 2014. ↩

- The United Nations Generally Assembly resolution 67/56 (2012) convened an open-ended working group to develop proposals for multilateral disarmament negotiations; subsequent civil society conferences on the humanitarian impact of nuclear weapons in Oslo (2013), Nayarit (2014) and Vienna (2014) underscored the necessity to strengthen nonproliferation and disarmament processes, leading to the possibility in New York (2017) of a convention banning nuclear weapons. On 27 June 2017, the United Nations conference to negotiate a legally binding instrument to prohibit nuclear weapons, leading towards their total elimination published its second draft (UN News Centre 2017). ↩

- Former Nuremberg trial chief prosecutor for the Allies, Telford Taylor, is quoted as saying "The rights of Hiroshima are debatable, but I never heard a plausible justification of Nagasaki." Cited in Taylor 2005, 30. ↩

- Pledging states are officially listed by the Austrian government, access the PDF. ↩

- In the full speech by US Ambassador Adam Scheinman, Special Representative of the President for Nuclear Nonproliferation did not mention that a wind-down in missile numbers coincided with the end of the Cold War, and since then the intense modernization of nuclear weapons, has reducing them in number but increased them in destructiveness. ↩

- Declassified Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade File 15/2850. 2015. See also Australia's statement at the Vienna Conference, 2014, and compare this with the statement made by a former Australian diplomat in Geneva, Richard Linnane, bearing a relatively intemperate message to countries like Australia. ↩

- Johan Galtung promotes "five main principles, the '5 Cs': 1. Be Creative 2. Be Constructive 3. Be Concrete 4. Be Compassionate. 5. Be Concise." (Transcend Media Service 2017). ↩

- The work of Interhelp in the late 1980s, based in the Lismore New South Wales region, did much to promote this understanding. Through self-reflection, anger and fear can cease to be prime motivator, so that nonviolence principles can guide action. ↩