Residual: Art Beyond the Event of Maralinga

by JESSIE BOYLAN

- View Jessie Boylan's Biography

Jessie Boylan is a photomedia artist based in Chewton, Victoria, and a lecturer in Photography at La Trobe University in Bendigo, Australia.

Residual: Art Beyond the Event of Maralinga

Jessie Boylan

A plinth signifies a memory, an act; an occurrence, an event.

WARNING

☢

RADIATION HAZARD

RADIATION LEVELS FOR

A FEW HUNDRED METRES

AROUND THIS POINT MAY

BE ABOVE THOSE

CONSIDERED SAFE FOR

PERMANENT OCCUPATION

1) Taranaki Test Site, Maralinga, South Australia 2011. Photo: Jessie Boylan.

And, there's another sign:

☢

KUKA PALYA

NGURA WIYA

(You can hunt, but you can't make a home here)

2) 'Kuka Palya, Ngura Wiya' sign at Maralinga, 2011. Video Still: Jessie Boylan.

For me, it is this second sign that is more powerful. For Anangu, Aboriginal Pitjantjatjara traditional owners relocated from Maralinga, not being able to return 'home' is like taking part of the spirit away and forcibly erasing culture and heritage. Ms Smart from Yalata (far west South Australia), for instance, has recounted how:

the old people wanted to go back to home... They wanted to sleep in that peaceful place, the red sand, is connected to their skin and their body.... makes them feel strong inside (Smart 2015).

For Anangu, such as Ms Smart, home is then central to story and place-making, home is site of memory, history and family.

Maralinga

Located 1200 kilometres north-west of Adelaide, Maralinga was once a landscape contoured by snakes and spinifex, mulga and malu1, but now, this land has been transformed from an open hunting range, a place for making camps or simply moving through, to a surface stripped of its original soil; soil in which tiny specks of plutonium became so populous it had to be scraped into pits three meters deep and capped with twelve inches of concrete, in an attempt to remove its very presence from the surface of this earth.

Plutonium and uranium fallout from 15 nuclear tests conducted by the British government between 1961 and 1963 contaminated Aboriginal lands. Although the British government declared the Maralinga site safe following a 1967 clean up, surveys in the 1980s proved otherwise, prompting a new clean up project. Conflicts of interest, cost-cutting measures, shallow burials of radioactive waste, and other management "compromises" have left hundreds of square kilometers of Aboriginal lands contaminated and unfit for rehabilitation (Parkinson 2002, 77).

This landscape is one of trauma and amnesia and the signs are not only a warning, but a reminder of the state of play. Once a home, now a prohibited zone and tourist site; The Maralinga Tours website claims:

Not Kazakhstan, not Nevada...but South Australia's Maralinga... Maralinga Tours -- an insight into our hidden past. Learn about a very, very dark chapter in Australia's history. One Tree, Marcoo, Kite, Breakaway, Tadje, Biak and Taranaki: innocuous sounding names that in the 1950's provided headlines in the British and Australian press that heralded a growing capacity for Britain to offer a nuclear deterrent to the perceived threat of the Cold War. Maralinga Tours will give you an amazing insight into this dubious period of Australia's History. (Maralinga Tours Website 2016).

3) Tour Group at Maralinga, 2011. Photo: Jessie Boylan.

Ever since my first visit to Australia's atomic testing ground in 20112, I had been rehearsing in my mind various ways to make sense of Maralinga. In a 2006 piece titled Maralinga: Theatre from a Place of War my colleague Paul Brown had written that it might be hard for Australians:

to stomach the idea that their country was actively 'at war' for more than a decade in the 1950s and 1960s... [Maralinga is] still contaminated and uninhabited, in the heart of a country where Cold War politics and science have had unrecognised impacts (Brown 2006).

The reality that Australia was 'at war' only truly sunk in once I was standing at ground zero, looking 360° around me at semi-flattened land, erased surfaces and windblown spinifex; the stark contrast with the white-skinned boffins3 conducting nuclear explosions in this semi-arid landscape was tantamount to the hidden realities of Australia's participation in the Cold War.

As soon as I had left I wanted to return to Maralinga to make work that expanded on what I had done previously, so when in 2014, I was invited to be a part of the Nuclear Futures community arts project at Yalata, it was a great opportunity for me to not only learn more about the stories and issues I had been focusing on in my work, but to make personal connections with, and hopefully make work with, the community most directly affected by nuclear testing at Maralinga.

4) 'Avon Hudson at Taranaki' clip from Maralinga Pieces, 2012 (1:12mins)

While the impacts of the British nuclear tests at Maralinga had very real and disastrous immediate effects, the ongoing impacts to health, connections to land and country, memory and history deepened over time. Some key questions being asked by the Nuclear Futures group were: what would the landscape and associated communities look and be like in the future? What role would art play in this nuclear future? And, how can the event of Maralinga be "inhabited by art" as commentator Jill Bennett asks:

Social and historical events, like wars or terror campaigns, of course, have no precise temporal boundaries; it is never clear when they begin or when their effects cease to be felt. They are structured by relations with other events, and they often involve long periods when it appears that nothing is happening. So can such events, as amorphous and indeterminate as they are, in some sense be inhabited by art, and what happens when they are? (Bennett 2006, 67-68).

Our response to the stories of Maralinga and intentions in making new work was to ensure that the 'event' of Maralinga was not relegated to a specific moment in history alone, but rather, showed it as situated on a continuum, ever-changing and presenting new complexities over time.

My involvement with the Nuclear Futures Partnership Initiative was as visiting artist for a series of linked community-based creative residencies with multiple atomic survivor communities. This project linked strongly with several themes I had been exploring at the same in my postgraduate studies, which expanded from focusing on a specific site or issue, to bigger questions or ideas about place, connections to land and country, history and its implications for the future (Boylan 2015).

I became more interested in establishing a process that was less a didactic call to arms, but rather a process that would allow for a contingency in photographic meaning and documentary storytelling (Sekula 1978, 859). It is this contingency that allows for fluidity in the meaning of the work, or, for something else to happen (a more visceral or emotive response perhaps) that allows the issue of Maralinga to speak about its place in the bigger picture---nuclear weapons modernization and disarmament, Aboriginal sovereignty, colonialism, war, greed, and capitalism.

The project resonated with me strongly and led to a new artwork titled Ngurini (Searching for home) a multimedia video designed for immersive installation which told the story of the forced relocation of Anangu-Pitjantjatjara from Ooldea as well as the establishment of a new home at Yalata.

Ngurini (Searching for Home)

My own journey to Maralinga, the discussions about 'home' (prompted by the sign Kuka Palya, Ngura Wiya), and my growing understanding of the many ways Maralinga was and still is 'inhabited' have often taken me back to the basics of Australia's colonial history. The notion of terra nullius (empty land) still lingers in Australian society and culture today as it did during the colonisation period of this country's history. An underlying belief in this concept is often why so much can happen out there (out of sight out of mind), e.g. atomic testing programs, large-scale mining projects, and interventions into Aboriginal communities. Terra nullius flows into the idea that the desert, or the outback, is the 'middle of nowhere', and this statement is repeated countless times in news stories, personal travel anecdotes and travel advertisements. The idea of 'the middle of nowhere' implies someplace strange and bizarre, perhaps a desolate or sparse location, or an unintended destination.

Yalata, in this colonial mindset, would be one of those 'middle of nowhere' places -- located a few kilometres off the Eyre Highway on the far west coast of South Australia and 200 km south of Maralinga. With a population of around three hundred people, Yalata is a dusty community with white sand, not far from the Southern Ocean. Its government-built houses and sealed streets are all contained within a 500m^2^ radius, and from there the extensive spider web dirt track system snakes out in all directions into the Mallee and bushland beyond.

5) Early Yalata Community. Ara Irititja Archive

"Yalata" is a name with uncertain origins. Some people in Yalata say that it's a Scottish word brought when the mission was established, others say that it is the name of a crater on Mars. Other possibilities are that it was named after a steamship (built in Germany in 1955), or that it is based on an Aboriginal word for 'oyster'.

Although Yalata was officially established in 1954, it was set up as a mission prior to that by the Lutheran Church and populated by Anangu people who were brought there following the forced closure of the Ooldea Mission in 1952 when Britain also commenced its nuclear testing program at Maralinga. The community was transferred to the Yalata Community Council in 1974 that then chose to cease its operation as a mission.

Many influences have shaped my understanding of Maralinga, and the Yalata family stories that would become the basis of Ngurini. Among those influences is a piece of film, a 1994 video shot at Ooldea by filmmakers Dave Clarke and Michelle Anderson and featuring Anangu elder Hughie Windlass. On the day the Ooldea mission was to close, orders had come in from the Government and military personnel told everyone that they had to leave. Hughie Windlass said:

It was a sad day, when we left... It wasn't a happy day, wiya [no], sorry, sad, gone, pack up and go, we could hear people crying, howling... I was crying, children were crying, because they lost the school, the church, [they] just went off, just start running, following their mothers (in Clarke and Anderson 1994).

Everyone started walking and families were separated in the confusion; some people went south, some went north, east and west. Russell Bryant, a community elder and Lutheran Pastor in Yalata said:

While they were walking, they were leaving their tracks on the ground so people can follow behind them... Some people were left behind, they never followed the tracks (in Boylan et al. 2015).

Between 2014-2015 I visited Yalata as an artist with the Nuclear Futures program six times, and each time we stayed in dongas that sit behind the old Yalata Roadhouse, now mostly abandoned, crumbling and decrepit, and made of deadly asbestos fibres too expensive to deconstruct -- although there are plans to redevelop the site into an arts and cultural centre and new roadhouse.

The tiny rooms, which come with functioning A/C systems, a single bed, fridge, microwave and electric frypan, are used primarily for contractors, or visitors like ourselves, who won't be staying for long. The roadhouse is about four kilometres from the Yalata community.

6) Collaborators Danielle Marwick, Rico Ishii and Paul Brown from the Nuclear Futures partnership initiative accessing the internet 'hot spot' at the Yalata Roadhouse accommodation. Photo: Jessie Boylan

The first project to arise from the Nuclear Futures partnership initiative in Yalata consisted of a series of digital storytelling and media workshops for younger women in the community, a men's sculpture project, and providing assistance to Christobel Mattingley who was working on a new book Maralinga's Long Shadow about the artist Yvonne Edwards (See Brown and Mattingley, this volume). During our time there it became clear that the story of displacement from Ooldea and Anangu traditional lands was one that needed to be a part of the Nuclear Futures public showcase. We had just finished making and showing two works that focused on Avon Hudson and the nuclear veterans story, Ten Minutes to Midnight and Portrait of a Whistleblower, as part of the Adelaide Fringe Festival and while the Anangu story sits parallel with the veteran story it is often overlooked or not fully understood. Members of the Yalata community -- Russell Bryant, Ms Smart and Mr Peters -- wanted to tell the story and make it public. So with very little time in the lead up to a showcase at QUT, we began work on Ngurini.

While editing Ngurini, the narration about 'home' kept leaping out at me, I questioned if I could ever understand what it meant to be permanently dislocated from 'home'. British travel writer, Robert Macfarlane has said:

Every place exceeds your knowing of it. When you're dealing with a geological context, its age exceeds your knowing, exceeds your comprehension. Deep time is dizzying and vertiginous (in Allen 2016).

I realized that as places exceed our knowing of them, so too do issues and ideas associated with them. While spending time in Yalata and hearing the Maralinga stories, the significance of the sign Kuka Palya Ngura Wiya, became overwhelmingly clear, so too did the deep impacts of Britain's nuclear testing program at Maralinga; more so than I had previously imagined.

Driving into community at dusk, puffs of smoke rise from the bush camps and from people's front yards, as life is lived mostly outdoors. At Yalata, our connections became most strong with the Bryant family, namely Russell and Rita Bryant whom we had met on our very first trip there. Each time I returned to Yalata I would bring back photos from previous trips to give back to the community. This time I was looking for Rita to give her some photos and found her at a camp in an empty plot with about seven other people sitting on the ground in front of a fire, outside of an old canvas tent constructed like a wiltja (traditional shelter). They were chatting and I sat down next to Rita who started to talk to me in a beautiful soft voice that mixed English and Pitjantjatjara so much I couldn't tell which was which.

7) Yalata Camp, 2014. Photo: Jessie Boylan

We organised to go out to dig for punu (tree roots for artefacts) the next day and it became a feature of the subsequent trips too. On these trips Rita would sit up the front and point and nod towards different old stations, camps, roads and other markers, describing her life as a young woman, at bush school with her teacher Mr. Minning, walking from one place to the next, learning about white and Anangu ways of life. She would go into detail about the kinds of food they would have at the school for lunch: "potatoes, onion, bread, sugar, tea," she would say, again and again, laughing as she remembered it.

As the roads snaked in all directions Rita would point out which one to follow, and sometimes when she didn't I would ask "which one, which one?" and everyone would laugh, Rita included, as they all ended up on the same track anyway. Along the way Rita taught us songs in Pitjantjatjara, what she would teach the children -- heads shoulders knees and toes -- all of us doing the actions as we drove.

8) Road into the scrub, Yalata, 2014. Photo: Jessie Boylan

Rita loved school and loved learning, which lead her to be an Anangu teacher when she was older. She also described meeting Barka Bryant, Russell's father, and how there was a photo of him dancing for her in the courting process. Barka was instrumental in getting the plutonium removed from Maralinga after he travelled with Archie Barton and Hughey Windlass to London, bringing with them two bags of Maralinga soil to Britain's Defence Ministry to demand that Maralinga be cleaned up and returned to the traditional owners.

9) Rita Bryant, still from Ngurini 2015. Image Jessie Boylan

For the development of Ngurini, we worked primarily with Ms Smart, as well as Russell and Rita Bryant and their family, who each provided narrative direction. We consulted heavily with them about what images we could use from the Ara Irititja Archive4 as well as what could be included from the footage and audio we recorded while there.

Russell was very keen to tell the story of the evacuation of Ooldea, in Pitjantjatjara and in English and we knew this would form the basis for the story. They took us out to the old sunken water tank at Ooldea and we all sat down to hear about the school days, and life on the mission. Russell mentioned Anangu coming across wombats for the first time, how and how "they were thinking, what is this? This is a good meat." Rita began drawing lines in the sand and teaching us the words for kangaroo (red and grey), wombat and bush turkey, "malu, wadu, gibra..." We then re-enacted the scene of walking in the sand from Ooldea to Yalata, with Russell and his sister Sharon as the stars, trying not to laugh while shooing Russell's little dogs out of the scene.

Driving back to Yalata, Rita continued teaching us songs in Pitjantjatjara, songs adapted from English: Noah took those animals in his ark | two by two by two by two... and Jesus loves me, yes he does, oh Jesus loves me...

10) Rita Bryant sings Noah's Ark

11) Danielle Marwick filming Ngurini with Russell and Sharon Bryant. Photo: Jessie Boylan

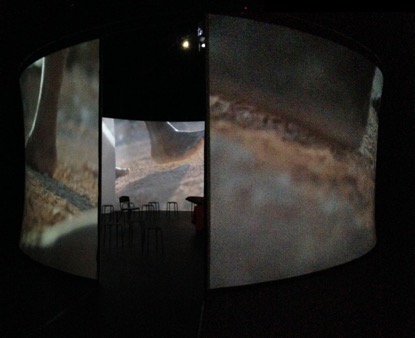

12) Ngurini installation: screening within a cylindrical arena. Photo: Linda Dement

Ahead of us were intense and concentrated periods of editing the content into something that could be digested, experienced and understood as a real story that is ongoing yet shifting over time. An ongoing and rigorous debate between artists centred on whether the content should be more abstract or more documentary, with the resulting work sitting somewhere in between.

Being entrusted with such a deep and powerful story was a great privilege as well as weight, a kind of collaboration that required mutual trust. When Ms Smart, Russell and other community members viewed Ngurini for the first time at the opening of the showcase at QUT in Brisbane, some were in tears and were extremely proud and happy that this story was being told in this way, for us this was a great affirmation that we had done the story justice.

Extract from immersive projection - link to video

Final Remarks

I believe, as an act of faith, in the capacity of art to bear witness to the inscriptions of history on people and place. Being in situ with people whose living memory contains that of the blasts has made it possible for the event of Maralinga to continue to be inhabited by art, to be inhabited by works such as Ngurini. Philosophers Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari argued:

It is no longer time that exists between two instants; it is the event that is a meanwhile... The meanwhile is not part of the eternal, but neither is it part of time -- it belongs to becoming (Deleuze and Felix Guattari 1994).

The story of Maralinga is one that is ongoing, inhabiting more than the part of history in which it was made, and it is art's great privilege to be able to be part of that 'meanwhile', reflecting, interpreting and inhabiting the space in between.

14) Rita drawing in the dirt, Still from 'Ngurini'. Photo: Jessie Boylan.

Works Cited

Allen, Rachael. 2016. In conversation with Robert Macfarlane, episode 80 of the Granta podcast, Web -- accessed June 20th, 2016

Ara Irititja Archive: website

Bennett, Jill. 2006. 'The Dynamic of Resonance: Art, Politics and the Event'. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Art, 7:1, 67-81.

Boylan, Jessie, Linda Dement, Luke Harrald and Paul Brown. 2015. Ngurini (Searching), Digital Projection. Directed by Jessie Boylan, Linda Dement, Luke Harrald and Produced by Paul Brown. Sydney: Alphaville.

Boylan, Jessie. 2015. 'Atomic amnesia: photographs and nuclear memory'. Global Change, Peace and Security, 28:1, 2015, 55-73.

Boylan, Jessie. This is not nowhere: photography, the campsite and the anti-nuclear movement in Australia. 2015. Unpublished Master of Fine Arts Exegesis. Melbourne: Monash University.

Brown, Paul. 2006. 'Maralinga: Theatre from a Place of War', in McAuley, Gay. (ed.). 2006. Unstable Ground: The Politics of Place and Performance. Berne: Peter Lang.

Brown, Paul and Christobel Mattingley. 2018. in this volume: 'Project Documentation for Maralinga's Long Shadow: the Yvonne Edwards Story', in Unlikely: Journal For Creative Arts.

Bryant, Russell. 2015. in Jessie Boylan, Linda Dement, Luke Harrald and Paul Brown, Ngurini (searching for home), Digital Projection. Directed by Jessie Boylan, Linda Dement, Luke Harrald and Paul Brown. Sydney: Alphaville.

Clarke, Dave and Michelle Anderson (directors). 1994. Hughie Windlass at Ooldea: Video.

Deleuze, Gilles and Felix Guattari; translation by Hugh Tomlinson and Graham Burchill. 1994. What is Philosophy? New York: Columbia University Press.

Maralinga Tours Website. 2016. Web, accessed 27th June, 2016.

Parkinson, Alan. 2002. 'Maralinga: The Clean-Up of a Nuclear Test Site'. Medicine and Global Survival, 7:2, 77-81.

Sekula, Allan. 1978. 'Dismantling Modernism, Reinventing Documentary (Notes on the Politics of Representation)'. The Massachusetts Review 19:4, 859-883. JSTOR Web

Smart, Ms. 2015. in Jessie Boylan, Linda Dement, Luke Harrald and Paul Brown, Ngurini (Searching), Digital Projection. Directed by Jessie Boylan, Linda Dement, Luke Harrald and Produced by Paul Brown. Sydney: Alphaville.

Footnotes

- Mulga, Acacia aneura, is a type of shrub or small tree native to arid outback areas of Australia. Malu is the Pitjantjatjara word for a red plains kangaroo. ↩

- I documented this trip in Boylan 2015. ↩

- A 'boffin' is a person engaged in scientific or technical research, a term usually used by the British. ↩

- "Ara Irititja" means 'stories from a long time ago' in the language of Anangu (Ngaanyatjarra, Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara people) of Central Australia. The aim of the Ara Irititja archive is to bring back home materials of cultural and historical significance to Anangu by way of interactive multimedia software now known as Keeping Culture KMS. Materials include photographs, films, sound recordings and documents. This purpose-built computer archive digitally stores these materials and other contemporary items and repatriates them to Anangu." Website ↩