Invisible Memorial: Augmented Reality at Maralinga

by LINDA DEMENT

- View Linda Dement's Biography

Linda Dement has worked in arts computing since the late 1980s. Originally a photographer, her digital practice spans the programmed, performative, textual and virtual.

Invisible Memorial: Augmented Reality at Maralinga

Linda Dement

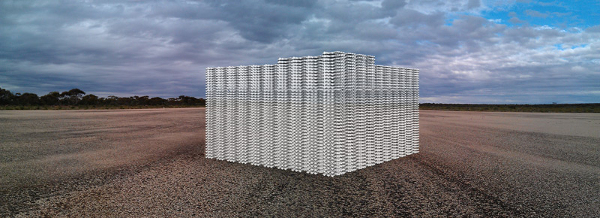

1) Stockpile of Babies Bones: image superimposed on Maralinga Airstrip. Photo and Augmented Reality by Linda Dement.

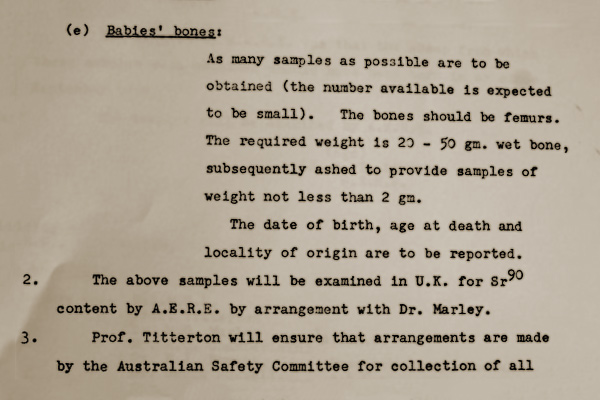

DEFE 16/808 1.(e)

Between 1957 and 1978 in hospitals around Australia, bones were secretly removed from 21,830 bodies. The bones were reduced to ash and sent away to be analysed for the presence of Strontium 90. One of the products of nuclear fission, Strontium 90 is a 'bone seeker', as is calcium, and if present in the environment deposits will invariably be found in human and animal bones, especially neonatal and infant. This was a program aiming to discover the extent and severity of radioactive fallout from the British atomic tests at Monte Bello, Emu and Maralinga (Walker 2014, prologue).

2) Detail from Defence Report DEFE 16/808, 1957, British National Archives

Defence Department Report DEFE 16/808 1957, outlines the specifications for samples to be taken from soil, vegetation, milk, animal carcasses and babies' femur bones. For the latter, hospitals in Adelaide, Brisbane, Melbourne, Sydney and Perth participated, excising femurs post-mortem, reducing them to ash and sending them on for analysis.

Although the DEFE report specifies babies' femurs, 20 to 50 grams, wet bone, it seems that femur and other bones from variously aged corpses were also taken during the 21-year program. (National Health and Medical Research Council Australian Health Ethics Committee Report 2002, 4)

Initially the ashed bone was sent to the UK for testing, then from 1970 to 1978 analysis was undertaken in Australia. The program was at first run under the auspices of the British Atomic Weapons Tests Safety Committee, then from 1973 onwards by the Australian Ionising Radiation Advisory Committee. (Redfern Inquiry Report 2010, ch 11 items 74--76)

3) Femur-no-shadow. Image by Linda Dement.

Ash

This secret violation of corpses was documented, government approved, paid, official business of Australian and British medical staff, technicians, bureaucrats and defense department employees for over twenty years (Walker 2014).

Permission was not sought from parents or next of kin for the removal of bones during autopsy, as indicated in the NHMRC Australian Health Ethics Committee Report (2002, 4). As this report recommended, there have been relatively recent attempts to return remaining identifiable ashed samples to the institutions they came from, and from there be available to any next of kin who might choose to enquire. Some remaining ashes are identifiable and some not.

No one is really sure who all of the 21,830 dead were. They don't have names. Their own mothers and fathers weren't aware of what was done at the time. If a child you know died in Australia during the years 1957 to 1978 perhaps they are one of those whose femurs was taken. Perhaps not.

In the scheme of the vast range of questionable intentions and immense damages assembled within the complexities of atomic testing in Australia, the abuse of these small bones is not the most outrageous offence. These beings had died from other causes well before their thighs were cut open. Probably none of them had received radiation doses great enough to cause leukaemia or damage the health of their grand-children. They have little cause for complaint in comparison to those on the ground during and after the atomic blasts, those forcefully displaced, those deliberately, accidentally and negligently contaminated, those whose pasts and futures and DNA are threaded through with the seeping black mist of the Australian atomic tests.

Intensive Care

Babies who die often do so after a time of traumatic, painful medical intervention in the germ-free harshness of well meaning hospitals. In 1988 I had a job printing photographs by Australian photographer Jonathon Delacour from his 1987 series Scenes of Every Day Life: 1. Intensive Care. The photographs were made during a period of residency in an infants' intensive care ward. Months afterward I worked in his darkroom producing prints of sick, dying and dead babies, their mothers, their fathers, their siblings, the tubing and blades and injections, the nurses and the clean bright floors.

4) Image from series Scenes of Every Day Life: 1. Intensive Care, Neonatal Intensive Care Unit, Children's Hospital, Sydney (May 5, 1987). Photograph by Jonathon Delacour. Used by permission of the photographer.

One photograph I loved was of a tiny dark round-faced girl, staring at the lens in what seemed to me to be pained indignance, with her lower body encased in casts and hoisted up in traction. She was a baby resentful of the assaults and inflictions she didn't understand, angry at the world for its intrusions, certain that the hardships of her every day life were unjust.

It is always children and their mothers who have historically borne the brunt of our institutional cruelty, and it seems that we still cannot think about that, acknowledge that the traumatic experiences of children are concreted into the foundations of the Australian nation state. (Wright 2018, 12-13)

21,830 small corpses, of most likely already traumatised beings, were desecrated to produce useful objects for the nation state at a time of almost war.

Maralinga Airstrip

In 2015 I stood on the Maralinga airstrip as part of a Nuclear Futures team. We were there to film and record material for artworks about issues of the cold war and governments, of atomic test veterans, of the displacement of Anangu people, of generations of cancers and over 20,000 years of contamination.

5) Linda Dement, Maralinga airstrip. Photo by Jessie Boylan 2015.

The massive Maralinga airstrip is the site that received the plane loads of personnel, equipment and materials that would eventually, as Strontium 90, infiltrate bones. It is the site where planes arrived with equipment and personnel essential to the testing of the atomic bombs that would disperse the toxicity. The airstrip itself, now a tourist attraction rarely used for planes, has the immensity, solidity and longevity of a memorial. Its kilometres of flat concrete and bitumen mark the comings and goings, input and output, transactions and transfers of this particular cold war project. It was the nexus, a concentration of traffic, intentions, weapons and substances, a field of transmission, a knotted juncture of vectors of toxicity.

21,830 small ghosts hover there in the ether, furious at the world for its abuse, concealment, theft and absence of accountability. They buzz Emu Field and Taranaki but return again and again to swarm and mill in agitation at the Maralinga airstrip. They find nothing but dead air, empty sheds and no one left to blame. Whoever took their bones is no one, is someone long gone, is a faceless bureaucracy, is a whole government, or two, or more, now disbanded.

6) Image of babies bones at Maralinga Airstrip using a phone. Augmented reality by Linda Dement. Photo by Jessie Boylan.

A.R.

Geo-located augmented reality (A.R.) allows the overlaying of digital information over a view of the real world on the screen of a mobile device. If a user is standing within range of a certain latitude and longitude, imagery, audio, video and/or digital 3D objects can be superimposed on their camera's view. It is an almost reality of elements that are, in terms of information, in that location and though they are invisible to the naked eye, can be revealed on screen.

21,830 Babies' Bones is an almost memorial, a virtual memorial for these nameless ghosts placed at the centre of their discontent, Maralinga airstrip. Precisely geo-located on the tarmac, virtual models of 21,830 infant femur bones stand in orderly stacks to honour these wronged voiceless dead. It is invisible, as are they, as were the scientists and bureaucrats and medical staff and defence force members who cut open the legs and removed the bones and burnt them to ash and sent them to labs.

Memorialization is a process that satisfies the desire to honor those who suffered or died during conflict and as a means to examine the past and address contemporary issues. It can either promote social recovery after violent conflict ends or crystallize a sense of victimization, injustice, discrimination, and the desire for revenge. (Barsalou and Baxter 2007, 1)

Memorials can also stand in mute solid resistance to elision, avoidance, invisibility and forgetting. They can stand firm with their arms folded and legs planted and refuse to let it slide.

7) Maralinga Aerial

Augmented reality can be placed anywhere, without permission, without consultation, without approval. It can be a virtual form of graffiti on the place that provokes outrage -- a sophisticated version of the black sprayed words scrawled on a building that houses some un-prosecutable guilt. Unlike graffiti, it can't be cleaned off. The augment will last as long as its hosting and its viewing app are available and even then, can be re-formatted, re-configured to suit the next app's technical requirements, and the next.

Information Wants to be Free

The very invisibility of an augment calls for its discovery. The allure of knowing something is here and that it can be found and seen through a device as personal and familiar as our phone, compels us to search. This dynamic articulates a variant on an old truism: 'information wants to be free' (Brand 1987, 202). It is difficult and constant work to keep a secret, to trap and press down information. Secrets try to push themselves out of our mouths at moments of weakness, drunkenness and intimacy. Secrets send a scent on the air to call in those who would track them down and uncover them.

In outlining an ethically accountable and politically empowering 'cartographic' approach, Rosi Braidotti writes of the requirement to

... account for one's locations in terms of both space (geo-political or ecological dimension) and time (historical and genealogical dimension), and to provide alternative figurations or schemes of representation for these locations, in terms of power as restrictive (potestas) but also as empowering or affirmative (potentia). (Braidotti 2002, prologue)

21,830 Babies' Bones offers a particular and situated perspective by engaging the tensions of invisibility: that which was deliberately hidden; that which is other worldly; that which is entirely in the techno-airwaves; that which can be found if only we will search. As an 'alternative figuration' it aims to empower the 21,830 angry ghosts giving them a visible/invisible form and through it, engage the living in seeking out one of the details of the geo-political historical past of this location.

Memory Object in the Ether

This intangible memorial needs to be sought out, called up from the ether and airwaves inhabited by the ghosts themselves. It is a bundle of zeroes and ones in transmission over fragile outback signals. It lives in the territory of vibrations and invisible beings called down via rituals and necromancy as well as by contemporary communication devices and constant connectedness. It is situated in the digital age and the past cold war, in the realties of hardware, software and past wrong-doing as well as the unrealities of the agitated spirits of dead unknowns. It stands invisible and immaterial, intermittent with poor signal strength, but persistent, a memory object for a swarm of angry ghosts and a refusal to forget the unscrupulousness of the powerful.

Works Cited

Barsalou, Judy and Baxter, Victoria. 2007. The Urge to Remember. Report from US Institute of Peace Working Group, Stabilization and Reconstruction Series No. 5.

Braidotti, Rosi. 2002. Metamorphoses, 1st ed. Cambridge: Polity.

Brand, Stewart. 1987. The Media Lab: Inventing the Future at MIT, USA: Viking Penguin.

Delacour, Jonathon. 1987. Scenes of Every Day Life: 1. Intensive Care. gelatin silver prints, National Portrait Gallery of Australia Collection.

Ethical and Practical Issues Concerning Ashed Bones from the Commonwealth of Australia's Strontium 90 Program 1957-1978. British National Archives.

National Health and Medical Research Council, Australian Health Ethics Committee. 2002. Defence Report DEFE 16/808, UK Defence Department, 1957.

Redfern Inquiry into Human Tissue Analysis in UK Nuclear Facilities: Report. 2010. Volume 1. London: House of Commons.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. 1995. Silencing the Past; Power and the Production of History. Boston: Beacon Press.

Walker, Frank. 2014. Maralinga: the chilling expose of our secret nuclear shame and betrayal of our troops and country. Sydney: Hachette.

Wright, Stephen. 2018. A Lantern Carried Down a Dark Path, Brisbane: Tiny Owl Press.