The Lost Garden of Recherche Bay: First Contact Plantings in Tasmania - Painting as Archival Countersign

by AMANDA JOHNSON

- View Amanda Frances Johnson's Biography

Amanda Frances Johnson is a writer and artist from Melbourne and is a Senior Lecturer in Creative Writing at The University of Melbourne.

The Lost Garden of Recherche Bay: First Contact Plantings in Tasmania - Painting as Archival Countersign

Amanda Johnson

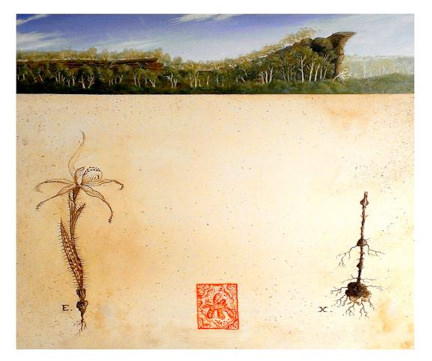

Gone to Seed: French Garden. Amanda Johnson, synthetic polymer and oil on canvas, 2015.

In pre-colonial, remote Van Diemen's Land, a French expedition planted a garden. Ship's gardener Felix Delahaye records for posterity that:

I had large quantities sewn everywhere in the woods, in the more open spaces and where the soil was more friable. It was not possible to sow any more in the soil[,] which is very difficult to cultivate, and in the season which did not allow it. I sowed mixed seeds everywhere thrown at random, where I believed they could succeed. (Duyker, M. 36)

That garden, located at the bottom of the known world, remains a romanticised site of eighteenth century knowledge discourse. In any case, the pre-settlement gardens sewn by French and English expeditions at Adventure and Recherche Bays failed (Duyker and Duyker; Mulvaney; Diane Johnson; d'Entrecasteaux; Labillardière), though William Bligh's stunted apple tree is mentioned in d'Entrecasteaux' posthumously edited Voyage records (Duyker and Duyker; d'Entrecasteaux). Two hundred and thirty years on, I recast the image of the dying tree for the exhibition, Friable, as mock-biblical tree in the garden of Eden and, as literal and metaphorical thorn in the side of colonial foundation myths.

This essay presents art works and research documentations developed in response to mythic inheritances around the French garden site for the exhibition Friable: The Lost Garden (Geelong Gallery 2015), arguing for ways in which painting may make a critical postcolonial response to the French expedition's first-contact botanical empire building, or 'colonisation by seed'.1 The essay begins as an historical essay situating the garden plantings in context; this section is then grafted to an exegetical section exploring the creative process of entering, critiquing and re-assembling the archive.

Drawing on Tasmanian field trips, French voyage archives and research frameworks from historian Bill Gammage, ethno-historian Bronwyn Douglas, art historian Alison Inglis and others, I aim to show how contemporary painting interrogates enduring terms of European visual connoisseurship: 'landscape' and 'garden' as well as powerful white myths of origin attaching to notions of first-contact plantings. To that end, I show how specific archival voyage texts (botanical, topographical and scientific) may be deconstructed and parodied in order to delineate ethical and intercultural postcolonial questions of environment, land and garden.

Lost Garden: Sky Blue Sun Orchid (Thelmitra jonesii). Amanda Johnson, oil and acrylic on canvas, 2015. Symbols used (Endangered [E], Extinct [X]) derive from classifications given in the Threatened Species Protection Act 1995 and Endangered Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999.

Introduction: Planting history

It is nearly two hundred and forty years since Indigenous Nuenonne and Lyluequonney encountered William Bligh (1788 and 1792 Bounty expedition) and Bruny d'Entrecasteaux (1792 and 1793 Recherche and Esperance expedition) at the remote Tasman South East Cape.2 Though these gardens perished and sank into myth, French navigator D'Entrecasteaux, and also the English Captain William Bligh, impose the earliest European agricultural templates in remote, unmapped Van Diemen's Land. As Alison Inglis writes:

The garden was not simply a symbol, it became a practical expression of eighteenth-century Europe's scientific and imperial endeavours, ranging from the landscape 'improvements' of Capability Brown, to the botanical fieldwork of the great expeditions of discovery undertaken by Cook (1768-79), La Perouse (1785-88), Bligh (1788, 1792) and Bruny d'Entrecasteaux (1791-93). On these voyages, the collecting of plant specimens often went hand in hand with gardening, as 'European seeds' (of fruit trees and vegetables) were planted en route, at various locations 'most favourable to their multiplication'.3 These gardens were intended to provide vital fresh produce for the expedition crews as well as future European visitors and settlers, thus forming part of the 'civilising mission' of the voyages.4 (3)

In 1792, the French planted chicory, cabbage, sorrel, radishes, watercress and potatoes at the northern end of Recherche Bay by Coal Pit Bight (Galipaud et al. 16). Scattered gardens are also evidenced as having been planted a little south of this site at Rocky Bay during a second French stopover in 1793. This expedition also deposited a pregnant nanny goat and a billy goat at Port du Nord and more goats at Adventure Bay (141, 161 Duyker and Duyker). The goats, as with the gardens, perished.

D'Entrecasteaux's journal entries, recorded during respective lay-bys at Adventure Bay and Recherche Bay, observe that the British had, some four years earlier, planted pomegranates, quinces, figs and apples. The British had carved an inventory of these plantings on nearby trees. D'Entrecasteaux also observed other inscriptions regarding watercress and cabbages (Duyker and Duyker 159)

The British plantings were made in relative haste; elsewhere, majestic blue gums (Eucalyptus globulus and Eucalyptus Obliqua) were being summarily botanised and cut down for ship's repairs and a myriad other functions.

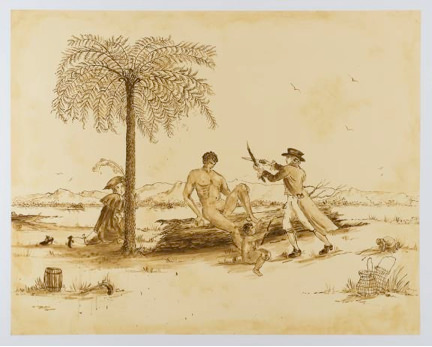

Ship's artist George Tobin did not record the plantings, but he recorded picturesque images of these majestic giants, often incorporating them into watercolour vistas that celebrated the British lay-bys and the proprietary nature of 'discovery', and this, at the expense of foregrounding Indigenous occupation (see collage re-working of Tobin's 1792 sketch 'Adventure Bay', below).

Adventure Bay without Adventure, after George Tobin. Amanda Johnson, collage on paper, 2015.

Bligh revisited Adventure Bay at Bruny Island in 1788 and, with botanist Nelson, planted on the east side of the bay a number of fruit trees that he had brought from the Cape of Good Hope.

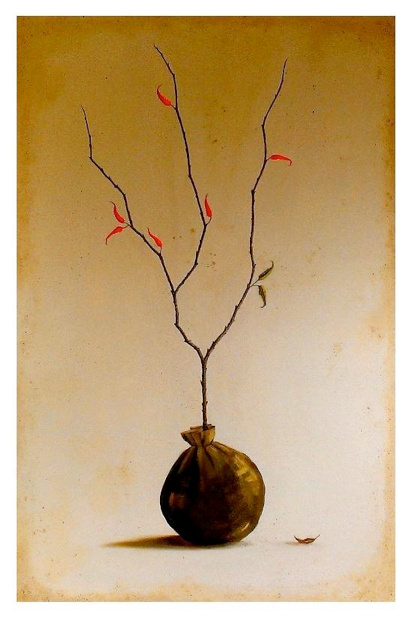

Bligh's Appletree: Stunted Varietal. Amanda Johnson, synthetic polymer and oil on canvas, 2015.

When Bligh returned in 1792, he found one apple tree still growing, the others having been consumed by fire. It is often said colloquially this was the first Granny Smith apple tree, though this claim appears to be an egregious exercise in colonial agricultural mythmaking. One-and-a-half centuries later, Tasmania would become known throughout the world as the 'Apple Isle'; but modern orchardist seed stocks bear no traceable bio-genealogical links to Bligh's original tree stock.5

Nonetheless, Bligh's and d'Entrecasteaux's ephemeral, vestigial pre-settlement plantings and gardens impose early European agricultural/horticultural templates, long before the settlement of 'Hobarton' in 1804.

Thus the global export of species from Tasmania - not only as conserved botanical exotics but as economic transplants, as with the idea/dream of the productive European garden - begins with these voyages. Other significant forms of cultural and intercultural exchange occurred as part of French botanical and horticultural exploration. Botanist Labillardière's collecting and naming of the majestic, hardy and fast-growing species Eucalyptus globulus (Tasmanian blue gum or Southern blue gum) is the prime example (Clode no pag).6

But soon after the D'Entrecasteaux expedition reached its disastrous terminus at the port of Batavia, the botanist's seed collections were confiscated; the ailing French expedition limped into the port of Batavia, only to discover that revolutionary France and the British were at war. The Dutch, an English Royalist ally, confiscated the French scientific findings and collections. But, within a few years, French collections were returned to France with signal intervention from Labillardière's colleague, English botanist Joseph Banks. Eucalyptus seeds were planted out within the 'Tasman garden' that featured in Empress Josephine's garden retreat at Malmaison. This task, ironically, was undertaken by voyage survivor, gardener Delahaye himself.

So, while the productive garden in Tasmania, untended, was inevitably shortlived, the translocation of indigenous seed stocks meant that Tasmanian native plants and trees were swiftly disseminated as exotics in European parklands and gardens. Seeds were exchanged from collection to collection, the economic potential of the tree swiftly exploited. Over decades, the blue gum became less of a parkland trophy than one of the most successful global cultivars, used mainly for railway sleepers, ship building, bridgeworks and paper pulp.

While on one level this distribution may be a happy economic story, naturalists, ecologists, and the United States National Parks service consider Eucalyptus globulus an invasive species due to its ability to quickly spread and displace native communities. It has also become a fire hazard across the state of California (Young). The practice of firing areas of wet schlerophyll forest by Indigenous Australian custodians in order to encourage the flourishing of open grasslands and sedgelands adjacent to forests of dedicated globulii is of course not part of American Indigenous land practice. As Gammage has noted in his magisterial account of Indigenous controlled burns, this practice was observed right through the remote South Cape areas from east to west to promote balanced species growth. He reminds us that the invasion of introduced species and the proliferation of unchecked native species:

... make 1788 hard to recognize now. It was even a different colour. It had more green grass in summer, much less undergrowth, and fewer trees. In 1888 it had more trees than in 1788, deceiving newcomers into thinking that regenerating forest marked virgin land. Today there are fewer trees on farms, swampland, and I suspect arid and semi arid country, but more in forests, national parks and remote places. Soil and water have changed, species have come, gone or moved. Australia is a world leader in animal and plant extinctions, reflecting how ancient and vital 1788s unnatural fires were. (Gammage 320)

But from the time of d'Entrecasteaux's and Bligh's expeditions, a Tasmanian export 'garden', or its most monumental symbol, Eucalyptus globulus, proliferated on a global scale. The Tasmanian garden was planted in situ, but through economies of exchange, its Indigenous counterpoint was also transplanted, however unsustainably, across space and time.

There are therefore many versions of the 1792 garden to consider, or at least many versions of the 'garden' arising from the 1792 French first-contact encounter at Recherche Bay. This in part enables the accreted romantic myth surrounding the actual kitchen garden planted on so-called Van Diemenonian 'wilderness' to be re-positioned. The kitchen garden may finally be seen and redrawn as one of many distinct outcomes of the imperial economic and cultural mission.

D'Entrecasteaux may have planted vegetables as a means of resourcing future lay-bys in what was a sheltered harbour, rich in fresh water and food, but his diaries also show, paternalistically, that he also designed the garden as a means of relieving the labour of the Indigenous women, 'this school of nature' which he witnessed spending long hours diving for crayfish and abalone (Duyker and Duyker 188, 234). Even Labillardiére, possibly naively, hoped that the naturalised offspring of Delahaye's seedstock might 'occasion total change in the manner of life of the inhabitants, who may then become pastoral people, quit without regret the borders of the sea, and taste the pleasure of not being obliged to dive in search of food, at the risk of being devoured by sharks' (Labillardiére vol 1. 79).

And yet, the French scientist's anthropological certitudes, riven as they are with Rousseauiste Europeanist assumptions around labour, culture, nature and society, provide a critical account of Lyluequonney and Nuenonne life where few historical accounts exist.

What is known is that the French garden was designed as a more planned and fortified construction than the random British attempts to propagate fruit trees. A formal garden design was undertaken by ship's gardener Delahaye while 'the savants' (the scientists and naturalists aboard) made exhaustive documentations of the plants, animals and landfalls of southern reaches of Van Diemen's land. The planting took place across a five-week lay-by in 1792 and during a second, three-week soujourn in 1793 when the French returned to Recherche Bay in some excitement, keen to see if the garden had flourished. It had not. Labillardiére observed:

I accompanied the gardener to the ground where he has sown different European seeds. This spot, which was very well dug for an extra nine metres by seven, had been divided into four patches; it afforded a soil in which clay was too predominant to ensure the success of the seeds that had just been committed to it. (Labillardiére vol.1, 175.)

On their return to the site in 1792, Labillardiére and gardener Delahaye found only disappointment. They happened across Lyluequonney people close to the garden location and:

... we took them to the garden we had created the previous year at Port du Nord. M. La Haye inspected it with more care than on the first occasion; he found that a few chicory plants, cabbages, sorrel, radishes, cress and a few potatoes had grown, but had only produced the first two seminal leaves. While he examined with extreme attention all the parts of this garden, one of the natives showed him the plants which he had lifted up; he was making a perfect distinction between them and the indigenous plants, although they were nearly imperceptible. M. La Haye ascribed with good reason, the lack of success of his vegetable garden to the seeds having been sewn in too advanced a season. (Duyker and Duyker 141-142)

Labillardiére records with manifest irritation:

... these plants would no doubt have thriven better nearer to a rivulet that we perceived to the westward. I had at least expected to find the cresses planted on its banks; surely this could have proceeded only from the forgetfulness of the gardener. 7 (Labillardiére vol. 2, 37-38)

An interesting question arises: how had the most brilliant botanists and practical scientific minds of revolutionary France (who had not met with any Indigenous people on their first lay-by at Recherche Bay) assumed that the European garden would be tended? Would it be tended by gods? Or by noble savages, who were, in French cultural parlance, close to gods?8

Archeological versions of the lost garden and the push for heritage

A general nostalgia pervades questions around the origin and the location of the French garden. This nostalgia, as much as the plantings themselves, remains a central driver for the exhibition discussed. But in 2002, the wider nostalgia threatened to become reality when an exciting archeological find was made. Stone fortifications were discovered by two white local environmentalists near the site of the Recherche Bay landings, were believed to be the stone structure of Delahaye's garden.

Photograph: Recherche Bay, proposed garden site. John Mulvaney, 2003.

The discovery was optimistically reinforced by historian and archeologist John Mulvaney and by historian Diane Johnson in turn. Poets, playwrights and folk singers celebrated the discovery of the garden and the French landings in a spirit of great optimism. The intensifications of garden fever built.

In January 2003, the entire north‐east peninsula was nominated for entry in the Tasmanian Heritage Register (THR). In February 2003, the Tasmanian Heritage Council provisionally entered in the THR 'La Haie's Botanic Garden' and the 'Observatory' on the north‐east peninsula. This registration laid the groundwork for land conservation initiatives of sections the Recherche Bay area spearheaded by Tasmanian environmentalist Bob Brown and entrepreneur Dick Smith. But, for environmentalists, historians and artists alike, a major obstacle existed in relation to field work around the designated heritage sites: the garden and environs at the bottom of the world were located on private land and slated for logging, rendering prosecution of land conservation claims impossible (Mulvaney 21).

While key historical documents provide information on the approximate locations of the various sites used and visited by d'Entrecasteaux, many of the claims had not been seriously tested. The objective of 2006 fieldwork carried out by a cooperative French-Tasmanian archeological survey, led by Jean-Christoph Galipaud, was 'to locate and study some of the onshore areas used during the d'Entrecasteaux expedition in Recherche Bay' (Galipaud et al. 9). The resulting report states that 'Detailed reconnaissance exploratory geophysical archeology surveys were carried out in order to complement the traditional methods of historical archeology' (Galipaud et al. 9). 'In most cases unfortunately, the information gathered was not sufficient to accurately pinpoint remnants of those activities' for which major claims had been made (9). As botanist Sib Corbett attested in a report prepared for the Tasmanian Land Conservancy:

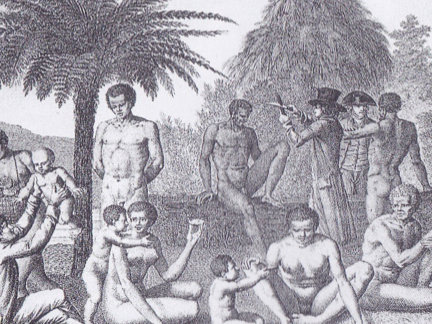

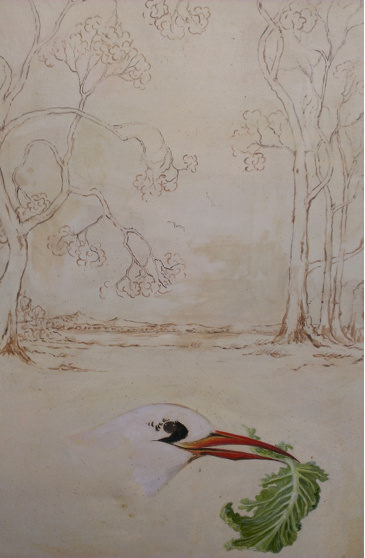

The site of the French garden lies on the northern side of the southern fire corridor, and is covered by eucalypts perhaps 100 years old. It seems certain the French would not have chosen a garden site in an area covered by gum trees. Finally, there is an engraving [see engraving after Piron, below] of French sailors and Aborigines together, in which a good deal of artistic license has been applied, but it seems likely the setting is on the Black Swan Lagoon. In the middleground is an isolated manfern, such as only happens after fire has removed the forest. (Corbett 37, quoted in Galipaud et al. 13)

Sauvages du cap de Diemen. Jacques Louis Copia (1764-99), engraving after a sketch by Piron, plate no. 5, Jacques Julien Houtou de Labillardière, Atlas pour servir à la relation du voyage a la recherche de La Pérouse, Paris, 1800. Expedition leader D'Entrecasteaux expostulated on French intellectual superiority on meeting Lyluequonney people for the first time: 'Oh! how much would those civilised people, who boast about the extent of their knowledge, learn from this school of nature!'

Neither Corbett nor Galipaud et al. speculate how Piron's neo-classical visual vocabulary, the exaggerated and stylised physiognomies and exploitation of a familial, arcadian narrative, reinforce idealising tropes of noble savagery in relation to Indigenous peoples. Galipaud et al.'s report notes, nonetheless, that as the 'stopover in Recherche Bay was the longest of the expedition, the idea that traces of the camp or of its impact on the area still exist is plausible' (Galipaud et al. 9).

But the elusive garden was not the only reason for Recherche Bay to attract considerations of heritage listing. For a range of numerous cultural, historical and environmental heritage reasons, foregrounded in a campaign team that included Bob Brown and Christine Milne, the Recherche Bay site (about 385 hectares) and surrounds was finally listed as a permanent reserve in 2005 (Australian Heritage Database).

Subsequently, and with grudging last minute assistance from the Tasmanian government, the privately owned site was bought out and provisionally entered on the Tasmanian Heritage Register in 2010 (Tasmanian Heritage Council). Somewhere in this newly acquired southern Tasmanian land conservancy, the original garden site, many amateur and professional enthusiasts concurred, might still be found.

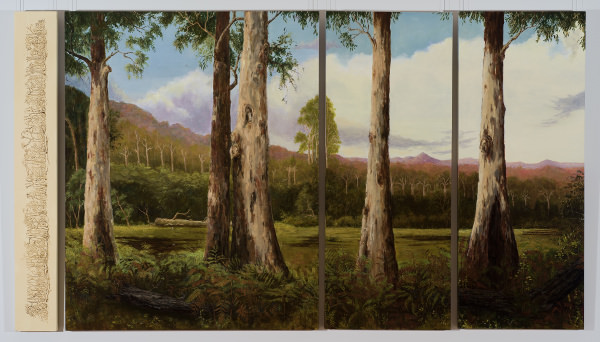

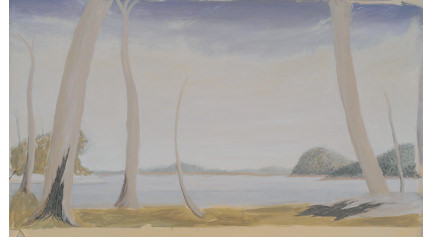

Tall trees/fired country/garden site, Amanda Johnson, synthetic polymer and oil on canvas, 2015.

Mapping methods

The Heritage Tasmania archeology report (Galipaud et al.) makes for relevant reading in relation to my unfolding postcolonial visual survey of these histories and their archives. It highlights fascinating anomalies from maps and drawings that show the garden improbably and variously located on an unsuitable dolerite outcrop. What is as intriguing as it is puzzling is that naturalist Labillardière and famed cartographers, Beautemps-Beaupre and Jouvency respectively, could hardly have made such acute errors unless the maps, perhaps, were adjusted later, just as the voyage journal of d'Entrecasteaux was posthumously edited by Lieutenant Rossel. The garden sited on maps of the area made by the French also appears aggrandised, overscaled. As Galipaud et al. attest, 'the discrepancy between the written accounts and the measurements on the maps indicate most certainly that the garden has been purposely drawn larger on all the maps in order to make it more visible' (26). The distance of the garden to the shore, at 150 to 170 metres, is nonetheless quite similar on all three maps compared by the archeologists (Galipaud et al. 26).

This stresses a symbolic importance for the garden, rather than an error, just as the variation of inscription suggests there can be no one true reading. Such imaginative notations provide clues for postcolonial creative work seeking to problematise official voyage records and the monological history that linear colonial maps convey. In my field trips I worked with these cartographic confusions, using old maps and new to physically retrace and document possible garden sites around Recherche Bay as sketches and photographs. This part of the process enabled me to exploit the historical archival discrepancies for new visual gain, and ultimately, through forms of painterly 're-mapping', suggest that there were and continue to be, many versions of the garden, mythic and actual.

Reproduced from Galipaud et al. 27. Several representations of the garden of Delahaye. A is the published engraving. B the colourised map, and C the final proof for the engraving. Note the difference in the layout between C and A.

The notion that the map might contain markings or inscriptions of symbolic rather than informational importance is supported by voyage journal testimonials showing that the esteemed expedition leader d'Entrecasteaux took a personal interest in documenting the garden on the maps that were made:

Various seeds sowed by M. Delahaye, gardener-botanist, might in future furnish supplies to navigators who will shelter in this haven, if however their produce escapes the destructive zeal of the natives who might mistake the new plants, the properties of which they are ignorant of, for all the other herbs which they seem to allow to perish with their fires. (D'Entrecasteaux, quoted in Duyker, M. 162).

We can only see it as a symbol of the French expedition leader's intention to take very seriously the role of the garden beyond that of food supply for the voyage and as part of a somewhat misguided, even poetical attempt to 'civilise' via imposed horticultural example. Elsewhere in his enormously readable Enlightenment Voyage account, d'Entrecasteaux writes, as mentioned above, of the garden as providing a form of economic relief relieving the backbreaking work of Indigenous women witnessed diving for shellfish over long periods (Duyker and Duyker, d'Entrecasteaux 162). Fruit and vegetables were therefore sewn as resources for the expedition lay-bys and, in the case of the French, as gifts to local inhabitants. Finally, though, in a traceable shift in tone, D'Entrecasteaux's optimistic 'school-of-nature' reportage and altruistic sentiment modifies into the mournful, racist inflection, for the Lyluequonney 'were not finally civilized enough to know the value or utility of such presents (Duyker and Duyker, d'Entrecasteaux 162).

D'Entrecasteaux explicitly asked that this garden be marked on the chart of the bay and this, Galipaud et al. deduce, rather too speculatively perhaps, but in keeping with Inglis' emphasis on the symbolic and cultural importance of the Enlightenment garden, that 'this can be taken as an indication that the Van Diemonian garden was meaning more to him than the generally performed spread of European plants of trees in newly found lands during 18th century expeditions' (Galipaud et al. 21). Galipaud et al. note that:

The time used to prepare the ground, the diversity of plants that were sown and the mapping of the place are indications of D'Entrecasteaux's will to acknowledge his visit with a lasting memory. A place with no fierce inhabitants or fauna, a climate close to the one in Brittany must have been an appealing place for a sailor. (21)

For the Lyluequonney people, who were used, in Gammage's terms, to maintaining their own sophisticated, delicate ecological maintenance of country via firing and seasonal migration to where food sources were abundant, the planting of introduced economic plants must have read as an absurdity.9 The garden, however well-intentioned, was a pro forma for colonisation by seed and by weed in Tasmania. It ushers in the dark side of 'gardening Australia'.

Bill Gammage, in his descriptions of what explorers would have seen in 1788, as opposed to what they might have seen in 1888, focuses on Botany Bay; this exhibition research more narrowly confines itself to French (and British) expedition visits to pre-settlement Recherche Bay and Bruny Island. Nonetheless, the Recherche and Adventure Bay coastal profiles appear strikingly similar to what French observers would have seen in 1792. For example, a topographical painting of wooded coastline of certain South Cape areas executed today may appear almost identical to watercolour studies made in the past.

But though sketched distant coastlines appear similar over time, the canopy and understorey retain likeness to 1792 in silhouette only, and Gammage's main points regarding rapid changes to country, initiated by the disappearance of sustainable Indigenous land practices (320), are crucial considerations. The understorey/canopy likeness at Recherche Bay is a remnant likeness; the ecosystem has been altered by introduced species, including weeds. Species loss has greatly impacted the area. For example, though a listed site, blackberries now thrive at Recherche Bay as part of a choking understorey that Sid Corbett (quoted in Galipaud et al. 13) argues would not have corresponded to the French's more capacious view in 1792 of cleared and fired coastal vistas punctuated by blue gum plantations.10

Heated topographical: warm coastal/cool coastal, Amanda Johnson, synthetic polymer and oil on canvas, 2015.

I set out to ironise the topographical view, pouring over works by Piron, Tobin and other voyage artists and mimicking the look of voyage documents that assumed that the natural world was one of endless bounty and profusion. Alongside, I examined other contemporary artists' responses to the Tasmanian landscape. In particular, I was drawn to examine the work of the late Tasmanian artist and printmaker, Bea Maddock. In her major 1998 work, Terra Spiritus ... With a Darker Shade of Pale, Maddock created a circumlittoral, incising and drawing 51 parts of the entire coastline of Tasmania, with each feature labeled with both the English and Aboriginal topographical names.11 In my own topographical 're-views' I emphasised the presence of smoke along coastal vistas as indications of Aboriginal presence and agency and also introduced images of dry-rooted seedling stock and weeds. Thus, I aimed to interrupt the long (and proprietal) view typical of the scenic genre, foregrounding the European's systematic approach to creating gardens in the antipodes as a colonisation by seed and weed.

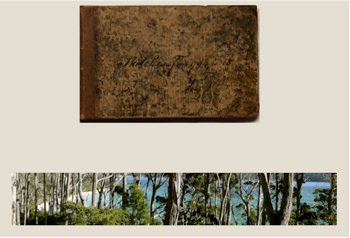

Sketchbook, George Tobin sketchbook, Watercolour on paper. 1792

This is the complicated ecological, cultural and economic colonial inheritance in which mythologies of lost gardens have played (and continue to play) an important ideological role. Ideas pertaining to first contact plantings have flourished in ways that the actual garden could not, did not, massaging the way for the agricultural ambitions of impending Tasmanian settlement, for associated ecological depredation and dispossession. Even now, idealised poetic tropes of the French garden contribute to a beguiling foundational narrative that diminishes subsequent impacts of colonial agricultures and resource-heavy industries. The garden is made and remade as a leafy arcadia in white colonial imaginaries, naturalising the take-up and decimation of Indigenous flora and fauna resources, the sowing of seed, any kind of introduced seed, as just and right.

Raiding voyage archives and undertaking field trips were clearly crucial methodological drivers for this painting project. But what critical frameworks did I avail myself of to help frame my research process and the unfolding pictorial results?

Planting the image: Archival countersigns

The creative research underpinning the making of Friable: The Lost Garden has been dependent upon gleaning visual countersigns, confusions and contradictions in the archival records (the stunted tree, the cartographic confusions, the words of journals, traces and non-traces in the biophysical environment) in order to evoke seams of contestation in the imperial story. Confusions in mapping the garden have been one starting point, suggesting an important 'countersign' for the pictorial imaging of this project.

In their book Oceanic Encounters: Exchange, Desire, Violence, ethno-historians Margaret Jolly, Serge Tcherkézoff, and Darrell Tryon use the term 'countersign'; they also eschew the term 'first contact'. They stress the necessity of decentering traditional accounts of initial meetings between European explorers and Pacific Islanders and, instead, advocate taking a critical look at a wide variety of meetings that resulted in confrontation and transformation on both sides of the encounter. Deploying historian Greg Dening's pivotal conception of the 'beach' as a site of encounter, the authors explore a diversity of meetings throughout a range of Pacific locales and moments in time.

I have variously mined French voyage and Indigenous and ecological, environmental accounts of South Cape country in support of field trip excursions to the South Cape. My experiences of the 'beach' and re-tracing of paths that French naturalists took during their lay-bys helped me to better imagine and to forge an understanding of intercultural encounters particular to this voyage. Field trips additionally furnished notational photographs and sketches which supported meetings and encounters with local Indigenous elders, settlers and experts across a range of fields. As a non-scientist, I had been constantly reminded of my studied, flawed efforts to grapple with botanical and ecological metiers. I needed to obtain a generalist's understanding of these fields, otherwise a postcolonial, parodic visualisation of the French garden's symbolic, botanical and ecological legacy could not proceed.

The big question, then, was how to assemble the comprehensive information and formulate it as a cohesive visual interrogation of an Enlightenment garden, exported to unsettled Van Diemen's Land. At one stage, embroiled in research, I was overwhelmed by the sheer amount of research 'gleanings', unsure how to resolve the pictorial project in a cogent way. I sat with the disparate information, the many sketches and photographs, but drew blank after blank.

I re-looked at the archivally informed print work of Tasmanian artist Maddock, her fastidious, exhaustive postcolonial topographics a hyper remapping of culture and coast. My topographical sketches were hardly geographically comprehensive, but they took from Maddock's work a sense of the vista from within and without. Could the topographical image be exploited further, I wondered? Could it be opened up to produce a sense of the imagined garden from the distanced arriviste point of view, which could then be contrasted with more interior, intimate views of the garden and its ruin? A combination of different kinds of views, conceived as material archival parodies, it seemed to me, might enable me to create new vistas and speak back to Enlightenment agendas of nature with an ecocritical voice.

As Mbembe (22) points out, the status of the archive is ultimately an imaginary one, regardless of whether the individual archival document exerts 'a debilitating power over doubt', and regardless of the impressively sacramental power of the thick-walled institutions (the sundry museums, libraries, government archives) that have evolved to consecrate the statuses of particular objects, papers and other items.

Even time, then:

[...] has a political dimension resulting from the alchemy of the archive: it is supposed to belong to everyone. The community of time, the feeling according to which we would all be heirs to a time over which we might exercise collective ownership; this is the imaginary which the archive seeks to disseminate. (Mbembe 21)

The final destination of the archive, according to Mbembe, is therefore 'always situated outside its own materiality, in the story that it makes possible' (21).

Mbembe's thought may be applied to visual art work or to the 'story' of the particular art work or painting that seeks to deconstruct colonial time and the reverential power of the archive. Or, in Indigenous terms, it might apply to the story of place or country where a dimension of epic time, markedly different to the teleological pulse of colonial time, always counterpoints ordinary time.

Bronwen Douglas, in her key essay on the scientific voyage of d'Entrecasteaux at the end of the eighteenth century, argues persuasively that the presence and agency of Indigenous people infiltrated the writings and pictures produced by sailors, naturalists and artists in the form of 'countersigns in the very language, tone and content of their representations' (175). 'Indigenous countersigns permeate voyagers' representations but are often camouflaged in the ignorance, prejudices and ethnocentric perceptual processes of European observers' (175), she says.

As Tiffany Shellam has noted, in support of Douglas's argument:

Using European (observers') texts to reconstruct the meaningful past actions of Aborigines (the observed) and their interactions with the newcomers can only be achieved by the meticulous scrutiny of such texts, by paying sharp attention to the author's tone, emotion and rhetoric. (6)

If Douglas and Shellam are right, that these countersigns can be identified through critical attention to disparities and correspondences between particular representations across a range of media, such countersigns are a key resource for artists and writers generally. Aside from contemporary Tasmanian artists' works, I began to look again at paintings and drawings from the period in which these voyages took place. Were there things I had missed, as other artists had once missed?

Over the garden wall and into the gallery: The final project

I took the time to revisit the early botanical and landscape voyage archives I had looked at once, twice, thrice: Labillardière, Tobin and Piron (as well as later artists of the Tasmanian view such as Glover, Tebbit, Piguenit, Maddock). Many works on paper, I saw, were replete with the damage of time: illusions of paper stains and foxing. I began to take notes, small visual quotations drawn from these artists' paintings and drawings of native and introduced species. Their visual documents conceived 'Van Diemonian nature', 'wilderness', 'Indigene' and 'garden' in particular ways. But what had the artists excised or distorted?

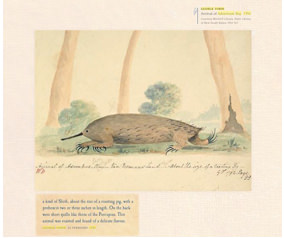

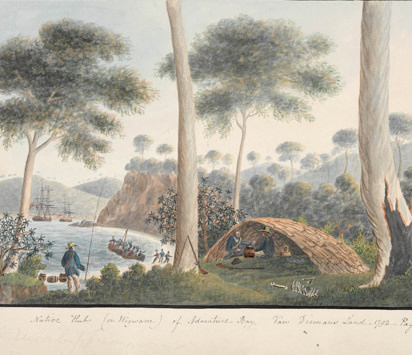

Tobin's and Piron's voyage drawings, made for two different voyages, suddenly struck me in differently influential ways. I re-looked closely at two Tobin watercolour sketches, View of Adventure Bay and Animal of Adventure Bay, both demonstrating grandiloquent plays of scale. Tobin aggrandises the body of a marsupial echidna, for example, as monster in an unpeopled Eden.

Animal of Adventure Bay, George Tobin, Watercolour on paper, 1792.

His repeat use of the same constructed landscape scenography in relation to the Adventure Bay site is the setting for many drawings, against which features of the new world, with the exception of Indigenous human beings, play out. In another sketch, Native Hut, or Wigwam of Adventure Bay, a Nuenonne hut is unusually foregrounded, occupied by awkward white 'picnic makers' who seem intent on 'trying out' the habitat of 'the other', without the niceties of exchange, without knocking, as it were. There are no signs of local people, who are only ever implied. Indigenous presence has been elided, become a house museum for the white visitors' purview.

Native Hut, or Wigwam, of Adventure Bay. George Tobin, watercolour on paper, c. 1792.

Focusing also on the aged surfaces of these documents, I examined various works for errors and mould, for scribbles and blotches. I upscaled the original paper documents, transferring sepia backgrounds into paint and onto large-scale canvas stretchers (see below), stripping out details signifying colonial inheritance (e.g. boats, ships, 'wigwams', officers, guns).

Working Sketch: Adventure Bay without Adventure. Amanda Johnson, oil and acrylic on canvas, 2016.

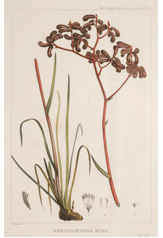

I also colour-heightened re-versioned botanical subjects, as if to parody early agricultural and botanical empire building. The original botanical samples, in the French instance, had been tenderly drawn with an assumption in mind that such flora would exist in perpetuity.

Anigozanthus rufa. Hand-coloured engraving, after Labillardière, 1808. Originally published in Atlas du Voyage à la Recherche de la Pérouse, No. 22. Labill. (Pierre Joseph Redouté, printer) 1797.

After examining Labillardière's detailed drawings anew, I wondered about melding contemporary classification symbols of species loss and extinction with painterly evocations of the original botanical classification notes.

Broken Fern, Asplenium polyodon. Amanda Johnson, oil and acrylic on canvas, 2015.

As Inglis writes of the final paintings:

... a particularly virulent orange pigment becomes the sign for botanical contagion. Vestiges of fluorescent paint can be found lurking throughout the exhibition - in a pool in a sketchy Glover-like landscape (Friable: Dirty Landscape (2015)), or sprouting from a sapling fruit tree (Reverse Archive: Blight's Appletree, Bruny Island, 1788 (2014)), or blown in the form of ember-like seeds across a distant plain (Seeded: Weed with Extinct Orchid (2014). (4-5)

My departure point was historical but, drawing on a range of archival sources and re-cueing certain information from postcolonial artists such as Maddock, I finally found ways to revivify the sepia nostalgia of the archival images. All the works had that in common: I used hints of bright colours while exaggerating the distressed, foxed surface of the original botanical prints. What I ended up with were large-scale paintings that drew attention, I hoped, in the best pop art sense, to mythologies of colonial progress in relation to fragile local ecologies and species loss.

Desecration of the First Kitchen Garden, Recherche Bay. Amanda Johnson, oil and acrylic on canvas, 2015.

Conclusion

The colonial imaginaries embodied in the images and texts of a particular set of voyage archives were, for me, compelling subjects for postcolonial visual interrogation. The exhibition may finally be considered as a postcolonial ecocritical imagining of first contact 'ecological imperialism'. That is the influential term of British environmental historians, Alfred Grove and Richard Cosby, whose work analyses 'the historical embeddedness of ecology in the European imperial enterprise' (Huggan and Tiffen 3). White settlement saw the violent appropriation of Indigenous land and the ill-considered introduction of domestic and non-domestic livestock and of European agricultural practices (Huggan and Tiffen 3). The Rousseauesque ethnographies and botanical activities of the d'Entrecasteaux landings at Recherche Bay interlink with, yet predate, more virulent forms of settler ecological imperialism in Van Diemen's land.

Though the French voyage was not a colonising mission per se, arguably the bringing of European seedstock and trees to the remote South Cape instigates 'colonisation by seed'. This seeding of the southern reaches of Australia with economic plants is the beginning, in the southern landfalls, of problematic agricultural exchanges that initiate the environmentally destructive and economically productive aspect of the broader colonial encounter, particularly colonisation by weed and the devolution, through dispossession, of appropriate Indigenous land management.

In ecocritical postcolonial terms, the exchange between the French and the Lyluequonney people of Recherche Bay can therefore be described as part of an originating ecological imperialism in which discourses of racism and sexism entwine. As Huggan and Tiffen (3-4) observe, Val Plumwood in particular has successfully attacked dualistic thinking structuring human attitudes to the environment,

where this is linked to the masculinist, 'reason-centred culture' that once helped secure and sustain European imperial dominance, but which now proves ruinous in the face of mass extinction and the fast approaching 'biophysical limits of the planet'. (Huggan and Tiffen 4, with quote from Plumwood 5)

In high-blown, deceptively universalist rhetoric, the original 'King's Memorandum' for the French voyage specifies that the voyage's first objective to find the famed explorer La Pérouse '... does not exclude anything else that might relate to the enlargement of human knowledge and to useful discoveries, [and as such] savants and artists capable of rendering this expedition interesting to all nations have been embarked ...' (Duyker and Duyker 281). The phrase 'anything else' intrigues with its implications of hierarchy and opportunism.

While no flags were planted, this was clearly a voyage intent on the colonisation of knowledge - scientific, ethnographic, botanical and geographical. In Douglas's terms, this voyage was '... a synecdoche for the era's dawning enchantment with primitivist idealisation of the noble savage (le bon sauvage) and its supplanting by negative, ultimately racialised attitudes better aligned with a new age of intensifying European imperialism' (Douglas 177).12

The monological voice of the d'Entrecasteaux's Voyage, which, though eminently readable, is also, as Douglas opines, 'irresistibly quotable for examples of the ethnocentric, infantilizing universalism of Enlightenment primitivism, with tropes like "this first natural affection" and "this school of nature"' (Duyker and Duyker 234, and also quoted in Douglas 183). 'Oh! How much would those civilised people, who boast about the extent of their knowledge, learn from this school of nature!' d'Entrecasteaux writes (234). Yet Duyker and Duyker write that there is genuine humanity and honesty in d'Entrecasteaux's statement regarding the Indigenous people that neither:

... in their behaviour nor in their customs, have we noticed anything that could weaken the good opinion we held them in. Oh! How much we should blush, on having suspected them of eating human flesh! They are interesting men in every respect, with whom I would have liked to have spent all the time we have been forced to remain at this anchorage. (Quoted in Duyker and Duyker xxxix)

The exhibition Friable: The Lost Garden focalises a European revolutionary period 'paralleled by a dramatic flux in anthropological ideas and vocabularies'; yet it is important to note that this period comes before nineteenth century ossifications of racialist cultural categories (Douglas 175). As Douglas argues:

This intellectual and semantic volatility registered an analogous series of discursive shifts which in some respects were embodied or pre-figured in the written and pictorial legacy of d'Enrecasteaux' voyage. In art, empirical naturalism supplanted neoclassicism. In literature, Romanticism displaced classical Enlightenment values including idealisation of the primitive. In the natural history of man holistic humanism gave way to the rigid physical differentiations of the science of race and in the process, the modern biological conception of race was distilled out of the term's older, ambiguous, environmentally-determined connotations of "variety," "nation," "tribe," "kind," "class," or sometimes, "species". (176)

My painting project therefore problematises '... the assumed centrality of white male European, actors in pre and post revolutionary expedition narratives and in cross-cultural encounters' (Douglas 175).

Stripped Landscape after Piron: Manfern and Man. Amanda Johnson, synthetic polymer on canvas, 2015.

Some paintings both mimic and parody the look of botanical documentations made by French white male actors who assumed, with Enlightenment confidence, that the planted garden, as with the documented botanical subjects and the garden of nature, could and would exist forever. The exhibition Friable contests voyage assumptions and mythologies built up thereafter, namely that the first contact French and British lay-bys in southern Van Diemen's land were, in essence, botanical and intercultural idylls.

Cover of George Tobin's sketchbook. Amanda Johnson, photograph, 2015.

Recherche Bay Landscape: Eucalyptus globulus. Amanda Johnson, photograph, 2015.

Works cited

Australian Heritage Database. "Place Details: Recherche Bay (North East Peninsula) Area, Southport, TAS, Australia." Web. 20 June 2017.

Barko, I. "The French Garden at La Perouse." Australian Garden History 24.2 (2012): 9-10, 34. Print.

Clode, Danielle. "Seeing the Wood for the Trees." Australian Book Review 366 (2014): 40-50. Web. 1 July 2017.

Corbett, Sib. "Appendix 3: Vegetation of the Tasmanian Land Conservancy block - Recherche Peninsula [2006]." Max Kitchell and Denna Kingdom. Recherche Bay Northeast Peninsula Reserve Management Plan. Hobart: Tasmanian Land Conservancy, 2007. 36-42. Print.

Douglas, Bronwen. "In the Event: Indigenous Countersigns and the Ethnohistory of Voyaging." Eds Margaret Jolly, Serge Tcherkézoff and Darrell Tryon. Oceanic Encounters: Exchange, Desire, Violence. Canberra: ANU E Press, 2011. 175-198. Web.

Duyker, Edward. "A French Garden in Tasmania: The Legacy of Félix Delahaye (1767-1829)." Pacific Journeys: Essays in Honour of John Dunmore. Eds Glynnis M. Cropp et al. Wellington: Victoria University Press, 2005. 21-35. Print.

Duyker, Edward and Marise Duyker. Eds and trans. Bruny d'Entrecasteaux: Voyage to Australia and the Pacific, 1791-1793. Carlton South, Vic.: Melbourne University Press, 2001. Print.

Duyker, Marise. Ed. and trans. "Translations of Felix Delahaye's 1792 and 1793 Journals in Van Diemen's Land (Tasmania)." Explorations 37 (2004). Print.

Fyfe, Mona. "When the applecart tipped." Griffith Review 39: 60-65, 2013. Print.

Galipaud, Jean Christophe et al. The Recherche Bay d'Entrecasteaux Visit in 1792 and 1793: A Tasmanian-French Collaboration Archaeological Project (2006): Final Report. Hobart: Heritage Tasmania, 2007. 90. Print.

Gammage, Bill. The Greatest Estate on Earth. Crows Nest, NSW: Allen and Unwin, 2011. Print.

Huggan, Graham and Helen Tiffin. Postcolonial Ecocriticism: Literature, Animals, Environment. London: Routledge, 2010. Print.

Inglis, Alison. "'Let us Cultivate our Garden': Re-imagining the Lost Gardens of Van Diemen's Land." Exhibition catalogue essay. Amanda Johnson: Friable: The Lost Garden. Geelong: Amanda Johnson, Geelong Gallery, 2015. 3-5. Print.

Johnson, A. Frances. Archival Salvage. Amsterdam and New York: Brill, 2015. Print.

Johnson, Diane. Bruny d'Entrecasteaux and his Encounter with Tasmanian Aborigines: From Provence to Recherche Bay. Lawson, NSW: Blue Mountain Education and Research Trust, 2012. Print.

Jolly, Margaret, Serge Tcherkézoff and Darrell Tryon. Oceanic Encounters: Exchange, Desire, Violence. Canberra: ANU E Press, 2009. Print.

Labillardière, Jacques-Julien Houtou de. Relation du voyage à la recherche de La Pérouse: Fait par ordre de l'Assemblée Constituante pendant les années 1791, 1792 et pendant la 1ère, et la 2e. année de la République françoise / par le Cen. Labillardière. Paris: Atlas, chez H. J. Jansen, imprimeur-libraire,1800. Print.

Maddock, Bea. "The makings of a trilogy." Art Bulletin of Victoria 31 [reissued online as Art Journal of the National Gallery of Victoria 31], 1990. Web. 29 November 2014.

Mbembe, Achille. "The Power of the Archive and its Limits." Trans. Judith Inggs. Eds Carolyn Hamilton et al. Refiguring the Archive. Cape Town: David Philip Publishers, 2002. 19-26. Print.

Mulvaney, John. "The axe had never sounded": Place, People and Heritage of Recherche Bay, Tasmania. Monograph 14. Canberra: ANU E Press and Aboriginal History Incorporated, 2007. Print.

Pascoe, Bruce. Dark Emu: Black Seeds: Agriculture or Accident? Broome, WA: Magabala Books, 2014. Print.

Plumwood, Val. Environmental Culture: The Ecological Crisis of Reason. New York: Routledge, 2002. Print.

Rozefelds, Andrew C. "Acclimatisation of Plants." Ed. Alison Alexander. The Companion to Tasmanian History. Hobart: Centre for Tasmanian Historical Studies, 2006. Web. 28 June 2017.

Rozefelds, A, R, MacKenzie, "A reappraisal of the weed invasion in Tasmania by the 1870s." Kanunnah (2004). Print.

Shellam, Tiffany. Shaking Hands on the Fringe: Negotiating the Aboriginal World at King George's Sound. Crowley, WA: UWA Publishing, 2009.

Tasmanian Heritage Council. D'Entrecasteaux Expedition Sites Recherche Bay and Adventure Bay: Provisional Entry to the Tasmanian Heritage Register, Hobart: Tasmanian Heritage Council, 1 April 2010.

Young, Kristal. "Introduced Species Summary Project: Tasmanian Blue Gum (Eucalyptus globulus Labill.)." 2002. Web. 30 June 2017.

Footnotes

- The exhibition, Friable: The Lost Garden was held at Geelong Gallery, 24 October - 6 December 2015. Individual paintings from this show exhibited subsequent to the exhibition include Gone to Seed (Bayside Art Prize 2016) and Dusk History: Two Tree Point, 1788 (Bruny Art Prize 2016). ↩

- Captain James Cook also very briefly passed this way, in 1777, prior to the colonisation of Tasmania, with ships Adventure and Resolution. ↩

- Inglis quotes specific instructions given to Delahaye (Duyker, E.), the gardener on board d'Entrecasteaux's expedition. ↩

- Aside from Bligh's and d'Entrecasteaux's plantings, Inglis also observes that La Perouse's expedition established a stockade, an observatory and a vegetable garden at Botany Bay during their six-week visit in 1788. This garden pre-dates that on Farm Cove, at Port Jackson. White settlement was established at Botany Bay by the English in 1788 (after discovery in 1770), and well before the mapping and colonisation of Van Diemen's Land, so colonial and pre-colonial plantings occur within distinct temporal, economic, political and cultural contexts (see Barko). ↩

- Discussing the history of the booms and bust of the apple industry in Tasmania, Fyfe notes that by the 1950s, the mythologically denoted 'apple aisle' supported an estimated three million apple trees in the state, with all most all of them in production. By the 1970s, the industry had gone quite literally pear-shaped (Fyfe). ↩

- Clode observes: ' ... Labillardière published the very first systematic, two-volume, exquisitely illustrated account of Australian plants: Novae Hollandiae Plantarum Specimen, as well as a bestselling book of his travels. Among the hundreds of Australian plants he described from his voyage were seven eucalypts (of the myrtle family), including Tasmania's floral emblem - the Southern Blue Gum.' Clode also observes the impact of the southern blue gum globally (Clode no pag). ↩

- In 1800, following his return to France, Delahaye was given the honour of being appointed Head Gardener for Empress Josephine Bonaparte's palace estate at Malmaison on the outskirts of Paris. Delahaye planted a Tasmanian garden for Josephine at this estate. ↩

- D'Entrecasteaux's and Labillardière's subsequent, perplexing irritation on finding the garden ruined on their second lay-by at Recherche Bay overlooks the fact that Aboriginal people moved up and down the South Cape coast, following burgeoning seasonal food supplies. Such lamentation feeds conveniently into myths of terra nullius; the visiting French did meet with Indigenous people on their second lay-by and were cordially received, but no evidence exists to suggest that the French negotiated the harvesting of blue gums for ships' repairs and for general burning. Nor was permission sought to plant out the garden. ↩

- Notwithstanding that Indigenous farming techniques were seasonably undertaken alongside and as interconnected with techniques of controlled burning. Indigenous historian and writer Bruce Pascoe, in Dark Emu, documents Indigenous agrarian farming histories and the extensive role of fish trap farming across Indigenous cultures. ↩

- Putting paid to myths of pristine wilderness, it is disturbing to learn that one-third of Tasmanian flora is introduced, with the most recent census of the weed species in Tasmania, published in 1999, listing over 740 naturalised species (Rozefelds). ↩

- As Maddock observed, '"Tromemanner" is a Tasmanian Aboriginal word from the Oyster Bay tribe meaning "my own country", as in "tribal land"'. ↩

- I have written elsewhere (see Johnson) and in more detail about the intercultural encounter between the French and the Nuenonne people of Recherche Bay. ↩