Curatorial Subjectivity: The Universal Aesthetics of Herbaria

by EMMA LANSDOWNE

- View Emma Lansdowne's Biography

Emma Lansdowne is a writer and horticulturalist based in Victoria, BC, Canada.

Curatorial Subjectivity: The Universal Aesthetics of Herbaria

Emma Lansdowne

In March of 2017, I had the opportunity to examine a nineteenth-century herbarium collection created by a British amateur natural historian, Christian Broun, Countess of Dalhousie. The collection of approximately 300 specimens, housed in the Royal Botanical Gardens Herbarium (HAM) in Hamilton, Ontario, Canada, documents various native plant species found on and surrounding her property in Southwestern Quebec in the 1820s. Each specimen was meticulously pressed, dried and mounted on its blank page, small strips of linen keeping the delicate plants in place. To see such a collection in person was a rare treat; I feared for the potential damage that could be inflicted by my clumsy hands, yet the pages and plants, despite their time-worn fragility, exuded a quiet strength. The drying of plant specimens remains one of the most successful long-term preservation methods in botany, and indeed, one can still make out minute details such as the veining on a leaf or the serrated edge of a petal. With each mounting comes a carefully scripted label in the Countess's hand denoting the plant's genus and species, the date and, in many cases, the location of collection. The Countess's specimens are a study in simplicity, allowing the beauty of the plants to speak for themselves, even now, nearly two centuries on.

Such beauty, however, reveals only a partial history. In the wake of Canada's celebration of 150 years of confederation, borne of the continuing consequences of settler colonialism, it behoves us to take notice of stories that are not told and cultural elements that remain invisible. In the pages of Christian Broun's herbarium, we gain little understanding of the region from which she collected her plants, or the particularities of the plants themselves - less still of the cultural significance of these plants to the Indigenous communities that may still have inhabited the area despite colonialism's best efforts. Indeed, the sanitised nature - however beautiful - of her herbarium makes it almost impossible to locate her specimens within their ecological, cultural and political contexts. These glaring gaps in imparted knowledge impel us to ask by what process did the Countess choose her specimens? And, by what criteria were plants included or excluded in her collection? Such collection practices are informed by a curatorial subjectivity that, functioning under the guidance of an aesthetic regime, requires deciphering to fully understand its cultural and sociopolitical significance. But the Countess is not alone in this exclusionary endeavour; rather, she is one in a long line of European natural historians who sought to understand, universalise, and exert control over the overwhelmingly diverse natural world and its infinite inhabitants with little regard for the cultural complexities that influence and are influenced by such a practice.

This essay interrogates the herbarium as an aesthetic practice, choosing as its site of inquiry late seventeenth- and eighteenth-century herbaria associated with European colonial expansion. Finding within the construction of herbaria a set of tensions between often conflicting but mutually reinforcing philosophies of natural history and aesthetics, I argue that the herbarium, as a form of creative engagement, is governed by a scientific aesthetic regime that creates and narrates political subjectivity through exclusion, denoted by visual conventions of clean simplicity and limited ornamentation and information. This exclusionary regime is largely guided by the universalising project of Linnaean taxonomy, which sought to unify all flora under a single classificatory system. Yet, the inescapably sensorial nature and impact of empirical observation and knowledge production remains evident in these herbarium collections, suggesting a more complexly layered set of aesthetic principles at work. This paper dismantles the layers of this scientific aesthetic regime to demonstrate the ways in which the eighteenth-century herbarium is an artefactual representation of the extractive colonial process of decontextualisation and alienation through natural history that supported a collective notion of European superiority and served the insidious colonial project of Indigenous erasure.1

Several decades of work by cultural theorists have exposed the significant power exerted by systems of representation in the production of meaning,2 and a long line of philosophers from the early twentieth century up to the present day have examined and debated the political nature of aesthetics, and the aesthetic nature of politics.3 Meanwhile, the fields of anthropology and cultural studies have increasingly focused attention on materiality and human subjectivity in the everyday.4 This wide range of work provides a valuable and intersectional critical framework through which to engage with and understand the curation and display of object collections. However, while museum studies has actively worked to recognise the inclusionary or exclusionary political nature of exhibitions (Lidchi 153, 205), the herbarium as both an aesthetic practice and cultural collection has not been given the same attention, despite the connection between colonialism and botanical classification that has been established. Keeping in mind the active role still played by herbarium collections in the present day, both as historical artefacts and cultural signifiers, I suggest that such an interrogation is not only timely but necessary to reiterate the pervasive political power of representational systems in both aesthetic and scientific practices, at the intersection of which we find, as exemplified by the herbarium, material expressions of human experience.

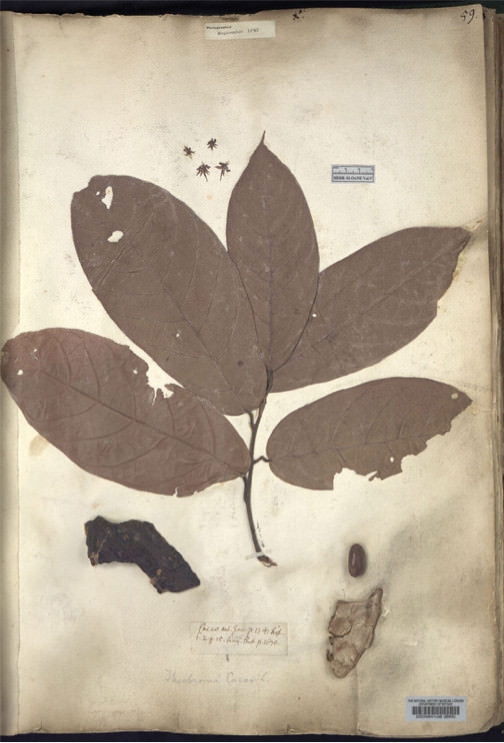

Figure 1: Theobroma cacao L., collected by Sir Hans Sloane, 1687-1689. Source: Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom.

The Herbarium: An Introduction

An herbarium is a collection of dried plant specimens, often arranged in sequence within an accepted classificatory system. The herbarium serves as an educational reference for scientific study, aiding botanists in the accurate identification of plant species, as well as providing useful historical botanical information in terms of plant distribution and availability. The practice of drying and pressing specimens has been in use in Western culture for over four hundred years, a testament to the longevity of dried specimens and the high degree of detail that is preserved. Its popularity grew steadily through the early modern period, and by the second half of the eighteenth century, the exchange of specimens between collectors had become commonplace and institutional collections were established. Herbaria continue to play an important role in botanical research and such collections have become a key reference source for taxonomists (Massey 1974). Plants also continue to be collected for use in herbaria, although the design of such collections and the informational detail they contain has changed significantly due to advances in technology and developments in the field of botany.5

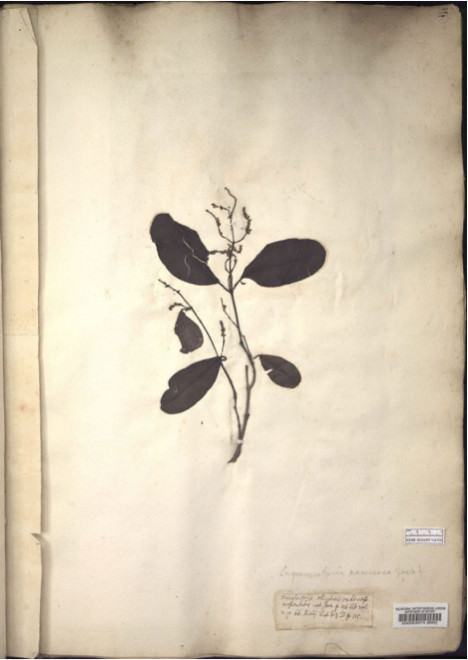

Figure 2: Laguncularia racemosa, collected by Sir Hans Sloane, 1687-1689. Source: Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom.

Beyond their value in scientific botanical research, herbaria may be seen to be cultural signifiers of the era in which they were constructed, reflecting the knowledge, value systems and, equally, the biases of their makers. Although herbaria as scientific material objects have traditionally been conceptualised as objectively framed specimens designed for the biological study of plants, it is my contention that such collections are a source of significant cultural information, based as much on what is excluded from the specimen page as what is included. Inasmuch as historical herbaria continue to be housed in publicly available museum collections and used in the study of horticultural history, their status as objects that reflect nuanced, politico-cultural histories cannot be ignored simply by dint of being "scientific" in nature. Natural historians, legitimised in their benign pursuit of knowledge, widely contributed to the European colonial project by way of possession through knowledge. Herbaria are the visual expression of this possession.

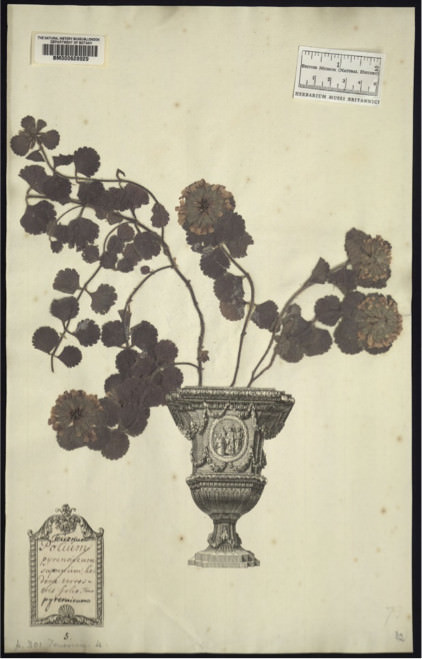

Figure 3: Teucrium pyrenaicum, collected by George Clifford, ca. 1720. Source: Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom.

That natural history, and botany in particular, exerted significant influence on European colonial expansion and commerce in the eighteenth century is widely acknowledged.6 While the roots of eighteenth-century botanical practices most definitively lie in early modern understandings of natural history, the eighteenth century saw significant and widespread developments in the systemisation of botanical study, aided by large and well-funded oceanic expeditions that sought out "undiscovered" and "unexplored" regions of the world. Most prominent among such attempts at classification was the development in the 1730s of a universal system of binomial nomenclature by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus, which remains the basis of botanical classification today.7 Several well-known herbaria collections were created during this period, including those of Sir Hans Sloane (1660-1753), George Clifford III (1685-1760), and Sir Joseph Banks (1743-1820). Their collections reflect widespread adherence to European taxonomical systems, which dictated the visual organisation of herbarium specimens, as well as the informational data included. While Sloane's specimens (Fig. 1 and 2) are labelled according to a polynomial taxonomy based on the work of John Ray ("A Specialist's Guide" 2),8 Clifford's specimens (Fig. 3) most likely originally adhered to Boerhaave's classification system of 1719, with changes later made in accordance with Linnaeus' binomial system.9 The majority of Clifford's herbarium sheets are adorned with ornamental urns as well as matching labels and ribbons with which to affix the specimens onto their pages, all of which were printed on separate sheets and then cut out and glued in place. Such urns were commonly and solely used in Dutch herbaria of the eighteenth century (Wijnands and Heniger 136-137). After having been bought and resold several times after Clifford's death, the herbarium was eventually purchased in 1792 by Sir Joseph Banks (ibid 142).

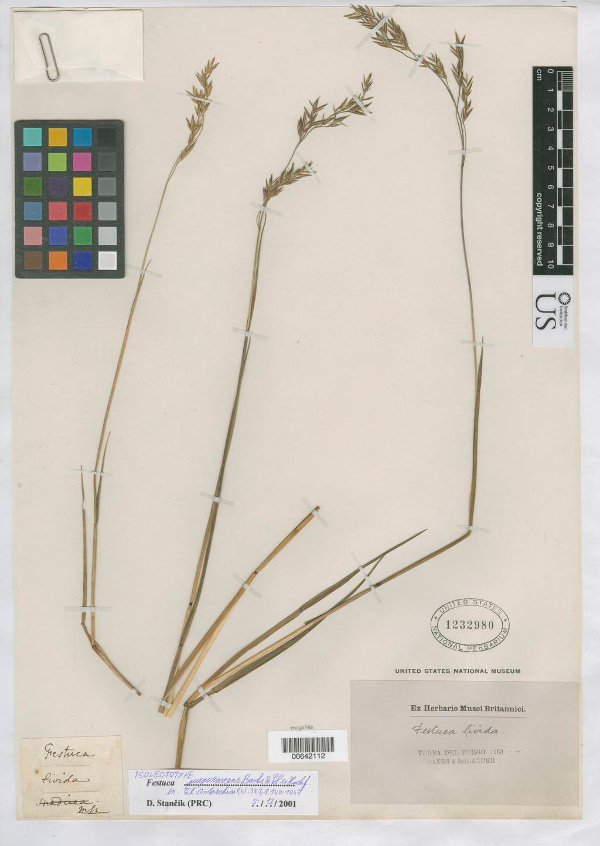

Figure 4: Festuca purpurascens, collected by Sir Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander, 1769. Source: Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, Washington, D.C., United States.

The specimens collected by Banks and Swedish botanist Daniel Solander (Fig. 4) during Captain James Cook's first voyage on the Endeavor (1768-1771) strictly adhere to the Linnaean binomial system. Over his lifetime, Banks greatly expanded his herbarium through exchange or purchase of additional specimens and whole collections. He particularly sought out herbaria with a Linnaean provenance, such as that of George Clifford III as mentioned above, and including Linnaeus's own collection as well as several others (Hodacs 6). For this reason, we can assume that the majority of Banks's amassed herbarium adhered to the binomial taxonomical system.

Unlike the collection of seeds or live specimens that carry with them the goal of future cultivation, the construction of herbaria is aimed at the long-term preservation of plant specimens which, through the modificatory processes of drying and pressing, become visual representations of plants rather than living ones - much like taxidermy, these specimens are an aspiration to life-likeness. The mounting of each specimen on a blank page enhances the impression of a plant that is no longer a plant; rather, it is a portrait of one, carefully framed by the toneless field against which it is set. Such construction, I argue, is a form of creative engagement, an aesthetic practice that offers a reductionist visual structuring of the natural world - what English scholar Jeffrey Nealon identifies as a "representational regime" (6). For Nealon, this regime refers to Foucault's understanding of an eighteenth-century natural history epistemology fundamentally based upon classification and naming of that which is visible on the surface alone; however, I suggest that Nealon's term can equally refer to the aesthetic qualities of the herbarium as a constructed material object that is fundamentally sensorial in nature.10 This essay will analyse and dismantle various manifestations of the aesthetic representational regime evident in the herbaria of Christian Broun and Joseph Banks. However, before doing so, I shall construct a theoretical framework based upon the aesthetic theories of Ben Highmore and Jacques Rancière. This short theoretical discussion is mandatory to the historical analysis that will follow.

The Sensorial World: A Convergence of Science and Aesthetics

While it can be tempting to situate the scientific and the aesthetic in separate and even conflicting realms in the study of eighteenth-century Europe, a re-evaluation of the nature and significance of historical herbaria underscores the ways in which the pursuit of science was informed by and expressed through the senses. Despite attempts "to represent their interests in terms from which passion was evacuated" (Thomas, "Licensed Curiosity" 118), eighteenth-century natural philosophers failed to convincingly separate the sensorial from their pursuit of knowledge, for the pursuit itself was fuelled by a passionate curiosity, a desire to understand the natural world (ibid 116). Indeed, empiricism itself, a basic tenet of natural history, made the inescapable presence of human passions abundantly clear.11 Enlightenment philosophers found themselves unable to dislocate the fickle sensorial self from empirical pursuits, at once requiring its capacity to perceive the world and decrying the unstable nature of such perception. As a creative product of the pursuit of knowledge, the herbarium resides at the intersection of science and aesthetics.

As the work of Ben Highmore makes clear, science and aesthetics converge in their shared goal of knowing and making sense of the world. In his argument for an aesthetic theory of the everyday, Highmore insists that art and 'reality' are inextricably connected.12 For him, the relationship between creativity and knowing-the-world can be explained through a study of aesthetics, for aesthetics names the subject as respondent to the sensate world; we perceive the world with our senses, and art is the expression of this experience (Highmore 23). Human passions - the varying results of our sensing of the world - are not passive, but rather inaugurate action, and it is here that creative expression finds its place. Eighteenth-century natural historians desired to expand their knowledge of the natural world, and this desire took creative expression in both abstract forms, such as the development of a taxonomical system, and material forms, such as gardens and herbaria. Foucault terms such material expressions "unencumbered spaces in which things are juxtaposed" (131); I suggest that, more effective than the living garden, herbaria allowed for a standardised form of representation that most closely resembled the table - the "non-temporal rectangle" that Foucault identifies as the "locus" of natural history (131).

If it was simpler for some eighteenth-century natural historians to ignore the problematic nature of human observation, it was for others a keen object of study, forming part of a more general investigation of human life. As a theorising of passion, aesthetics at that time was "aimed at both describing the \'lowly\' realm of sensorial perception and directing sensitivity towards virtuous goals" (Highmore 22). These goals developed from the understanding of passions as external forces that motivate human action (Highmore 33). For natural philosophers such as David Hume, these external forces carried an inherent danger that could only be addressed through principles of good taste.13 For Hume, belief in a universal standard of taste offered a solution to manage the "bundle of different perceptions" which existed in "perpetual flux and movement" (Hume, Treatise sect VI par 4); and the discernment of taste required experience, cultivation, and practice (Hume, "Taste" 7, 9). Hume's belief in such a standard is echoed in the observational practices of eighteenth-century natural history, in which certain visible distinctions of things, specifically, sound, taste, and smell, were considered subjective, and therefore unreliable.14 Although sense of touch was acceptable, its capacities are narrowly limited, leaving sight "with an almost exclusive privilege" (Foucault 133). As I will discuss in further detail in the following sections, it is in the wake of these exclusions that the herbarium finds its place as a pedagogical material expression of natural history. The herbarium offered a simple, universally recognisable format of visual representation complete with binomial taxonomical labels.

The empirical practices of Hume's discernment of taste and the study of natural history share an adherence to a hierarchy of perceptions that reflect their common historical, socio-cultural and political contexts.15 The importance attributed to experience and observation in the accumulation of knowledge rested upon a necessarily tangible, material world against which inductive generalisations could be measured. Equally based upon sensorial perception, the discernment of taste and the discernment of species employed a system of comparison based on relational similarities or distinctions; the herbarium was a tool in the amassing of material objects whose comparative existence would point to larger, objectively proved systems. Yet, in a show of collective denial, creators of herbaria held a profound belief in their capacity for detached contemplation. As expert witnesses, naturalists were imbued with the authority of "truthful" representation; the network of signs and symbols borne from a naturalist's observations made manifest what they and their patrons believed to be an "exact knowledge of nature" (Lafuente and Valverde 135). However, natural history was not simply a method of depicting the planet as it was; rather, it was an interventionist process of imposing order (Pratt 31). The scientist was seen to have a discerning eye that drew the world out of chaos and entanglement and into a system of global unity (ibid). As will be shown in the historical analysis below, the desire to find order in chaos exemplifies the way in which the herbarium collector, as an aesthetic author, responds to his or her own sensate world and, through the affective production of this instinctively curatorial work, becomes source, communicator and redistributor of the stimuli of the world. While the eighteenth-century natural historian may attempt a clinical, empirical pedagogy, the herbarium is necessarily drawn from personal, sensorial experience that, through its aesthetic construction, becomes transpersonal in its communicability.

Political Aesthetics: Colonial World-making through Material Culture

As Highmore's discussion of aesthetic theory reminds us, the value placed on so-called 'tasteful' intellectual pursuits such as the study of natural history contributes to a wider collective program of creating and maintaining power (45). With this in mind, if it is true that cultural and intellectual value is drawn from the notion that aesthetic experience necessitates standards of taste, the cultural expressions governed by those standards will necessarily continue to perpetuate the same value judgements. Highmore asserts that while experience leads to artistic, cultural expression, this expression in turn informs experience (42);16 creative expression both shapes and is shaped by our experience of the sensate world. To return to the notion of value, then, creative expression equally shapes and is shaped by applied values. This process Highmore terms a transpersonal sensual pedagogy, or, what Rancière refers to as a "distribution of the sensible" (Highmore 53). This distribution of the sensible "organises a historically specific orchestration of what is seen or felt as notable, perceivable, valuable, noticeable and so on" (Highmore 23). For Rancière, this distribution of the sensible resides within the aesthetico-political regime (Rancière 1).17 The ability of creative engagement to create and narrate power and meaning effectively exemplifies the ways in which the sensible cultural world may be managed by aesthetic regimes that serve to define the field of social and sensorial perception. If aesthetics sees the individual as respondent to the sensate world, a distribution of the sensible under an aesthetic regime is a collective response to and imagining of the world. Thus, as we will see the plant specimens preserved by Banks, on the collective level, the herbarium is a political pedagogical tool that creates and maintains a perceptual reality built around a European scientific system of knowledge that assigns privilege to European hegemony. Its design as a material object, or in other words, its aesthetic regime, contributes significantly to its efficacy in this sensorial, political, pedagogical process.

The distribution or management of value schemes within the aesthetic regime of the herbarium takes place through processes of decontextualisation and exclusion, reflected in its visual construction. Plucked from its natural environment to be pressed and mounted on a blank page, a plant specimen destined to be part of an herbarium was forcefully relieved of its environmental, historical, and cultural contexts - deemed to be of no value - and, renamed in Latinised scientific terms,18 was given a new identity divorced from its own ecology. As I will discuss in more detail below, the plant became an aesthetic representation of European scientific knowledge that reinforced the intellectual superiority of not just the individual collector but the colonisers as a collective force, and this intellectual superiority became a collective notion upon which the complex hegemony that defined the relationship between European and non-European was based. The knowledge accumulation and dissemination that took place within the engines of colonial expansion and of which botany was a particular focus must be understood as a distribution of the sensible - the drawing of attention to something considered worthy at the expense of many others that are not and as such, a large-scale designation of what and/or who will be visible or invisible. Such designation or distribution worked to reaffirm the political power of European nations bent on the colonisation and/or exploitation of new lands through the aesthetic constitution of an abstracted world that could be visually dominated with the drawing of maps and the categorisation of collected specimens.

In general terms, the herbarium is a collection of specimens, one whose significance to the pursuit of scientific knowledge is almost entirely dependent on the mutual comparison of those specimens and, therefore, their collective existence (Pearce 301). However, if the pursuit of knowledge is part of a wider program of not only understanding the world but controlling it, the collection of specimens must also be understood as an essential facet in the creation of an abstracted world that this human control necessitated.19 If, as French philosopher Bruno Latour argues, possessing a place equates to possessing knowledge of a place, bringing new knowledge back to the bosom of power requires material evidence that proves the possession of this knowledge, such as maps, ethnographic objects, live specimens and/or herbaria. This process Latour terms a "cycle of accumulation" (ibid 220); each cycle permits additional explorations equipped with greater knowledge and, therefore, greater power, tipping the balance in favour of the encroaching Europeans (Latour, Science 221).20

But while Foucault finds the "power of writing" to be an essential component in these machinations of power (Foucault, Discipline 189), it is clear from Latour's work that the visual object is of equal, if not greater importance. Possessing a faraway place through knowledge is a mobilisation of events, places and people through a change of scale that is visually expressed.21 The geographer reduces the world to the size of an atlas; the botanist reduces the seemingly infinitely varied flora of the world down into a single classificatory system represented by a stack of dried specimens.22 The visual apparatuses of natural history, as much as or more so than the written accounts of voyages, were the basis of the global knowledge-gathering that propelled European hegemony (Pratt 15). The expression of this hegemony through a mobilisation of worlds is the creation of "centres of calculation" whereby a group or individual in a single geographical location has the power to act at a distance on many other points (Latour 222). To put it in Ranciérian terms, a centre of calculation is as an aesthetico-political regime, and the accumulation and subsequent dissemination or use of knowledge is a distribution of the sensible, a making of worlds within which are drawn lines of social, economic and political division.

There is no doubt that the herbarium facilitates the making of such centres of calculation. In utilitarian terms, the herbarium was a reliable sort of material object, allowing for safe preservation of specimens that could be efficiently stored with minimal space and withstand long voyages. Latour highlights three criteria necessary for a successful accumulation of material evidence: it must be mobile; it must be stable; and it must be combinable into collections of various sorts (Science 223). We can see that the herbarium surpasses the option of live specimens in meeting these criteria, therefore it was the ideal material representation of botanical knowledge .23 And, like the map that allows ownership of a coastline, the herbarium provides "the ability to visually dominate all the plants in the world" (Latour, Science 225). As such, the herbarium transmits a narrative of constructed power and meaning.

Curatorial Subjectivity: Collection and the self

Eighteenth-century collections of exotic material objects lent themselves to a conception of the world as an "enframed totality" (Mitchell 227) that, through the display of such objects, could be visually construed as reality. More, perhaps, than other material objects, natural history specimens lay claim to an objective truth: rather than their painted or drawn counterparts, collected plants are just that - real plants turned souvenirs - therefore the legitimacy of the knowledge they impart has, until recently, largely been taken for granted. Yet, the knowledge that herbarium specimens carry with them is, consciously or unconsciously, constructed. Like all modes of sensible distribution, the herbarium has the power to define what shall be visible or invisible, acknowledged or unacknowledged. In the eighteenth century, local knowledge of indigenous communities encountered during European exploration was depended upon for the successful discovery and accumulation of new floral species, yet that local knowledge was later ignored and deemed to be of lesser value or, in many cases, invalid.24 For Linnaeus and his disciples, universality was the proper object of natural history, and visual representations of his classification system in the form of herbaria underpinned this goal through a reductive scientific aesthetic regime.25 In utilitarian terms, this simplified structuring was useful to colonial enterprises, intended as it was for prompt production (ibid 329), for any reduction in time and hard work led to greater economic efficiency (Lafuente and Valverde 141), and the basic format of herbaria would have saved the botanical collector a fair amount of time.

Moving beyond the design of herbaria, however, I suggest that an engagement with the choice of plants will offer significant insight into the curatorial subjectivity of the collector and his work. Equally important as the number of plants on each page, or the labels that record limited data, are the types of plants that were chosen as new additions to a collection. The general idea, of course, was either to catalogue the plants of known regions or to discover new species in a given region requiring inclusion into a taxonomical system, and to preserve them by drying and pressing for future reference. This does not mean, however, that all new species in each region were collected, due as much to the varying interests of the collectors as to issues of accessibility and time. Specific fascinations with types of plants, such as trees, shrubs, perennials etc., could lead to thematic collections, and the ostentatious beauty of a flower often drew greater attention than, for example, a species of scrubby grass. Those plants that were considered "weeds" in familiar regions were always excluded, as were cultivated plants.26 The herbarium of Christian Broun, for example, appears to consist almost entirely of native or naturalised species, with only two cultivated specimens included in the extant collection (Pringle 15). Although it is possible that the collection is incomplete, anecdotal evidence suggests that the Countess had an aversion to collecting familiar European species, and chose to focus on Canadian native species that were novel and, for whatever reason, of aesthetic interest to her (Galbraith). Likewise, Sir Hans Sloane omitted several common species in his herbarium of plants from the West Indies, including Swietenia mahagoni, the West Indian Mahogany, now quite rare, Portlandia grandiflora, and Cordia gerascanthus, all of which would have been quite accessible to him ("A Specialist's Guide" 5); his reasons for such omissions remain unclear, although we do know that as a trained physician, he had a special interest in plants with medicinal properties. The curatorial subjectivity necessarily guiding the compilation of herbarium specimens supports Highmore's notion of sensual pedagogy, in which the creator is affected by and simultaneously affects, communicates, and distributes stimuli.

A closer look at the relationship between the collector and the collected object, however, points to a more personal aspect of collecting practices: that of possession. Jean Baudrillard, in his "Systems of Collecting," argues that the foundation of object collection is our passion for personal possession, which he calls "a process of passionate abstraction" (7-8). This kind of possession has the effect of divesting an object of its function and making it relative to the subject (possessor).27 This relationship between subject and object represents a system through which the subject seeks to construct his world, or "personal microcosm" in an "enterprise of abstract mastery" (ibid). Collection, then, is a subjective process and system of meaning-making, of world-making, designed by the collector. Indeed, Baudrillard terms the collected object an "ideal mirror" in that it reflects the collector's desires.28 In this way, we can read the choice of plants in an herbarium as a reflection of the plant collector's desires. We can imagine that the Countess of Dalhousie, in passing over the weeds and non-native plants, unconsciously exposes her desire to imagine a frontier landscape of undiscovered plant species, revelling in the novelty of a New World. Or, for someone as enterprising and commercially-minded as Banks, his collection might reflect the desire for an uninhabited landscape rich with botanical resources. But as Baudrillard points out, the mirror is ideal in that it does not reflect what is in fact real; collected objects, he suggests, are the site of "tenacious myth" (11). The Countess's landscape, rather than being an undiscovered frontier, is in fact already occupied - both by indigenous communities who would most likely take issue with her labelling of many plants as weeds, and by colonists who have introduced familiar European species in order to recreate home; and the plants of Banks's collection are invested with complex histories and carry rich local meaning. Collection is a curatorial process of world-making based on inclusion and exclusion whose structure and content are reflective of and constituted by the subject.

Artefactual Representation: Natural history collections in the museum

The myth-making identified by Baudrillard in systems of collecting brings to mind traditional museum practices in which representations are generated and value and meaning are ascribed according to culturally and historically specific schemas (Lidchi 160). As a collection of objects that gain meaning through their categorisation and their very place in a collection, herbarium specimens are situated, like those in a museum, in the precarious position of having the power to mobilise and support specific classificatory systems that operate within often-fraught political frameworks.

The collecting practices of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century naturalists led to a stockpiling of various kinds of specimens that found their way into cabinets, museums, and university collections. Still extant in collections across the globe, herbaria are what I call artefactual representations of the "inflexible theoretical frameworks" (Schiebinger 128) that informed the colonial project, whose interpretive biases are made manifest in a scientific aesthetic regime. While colonialism is by no means a bygone global project, the historical herbaria found in present-day museum collections are artefacts of empire, standing as visual illustrations of the scientific tenets of eighteenth-century European colonial expansion. Equally, however, herbarium collections reflect the larger problematic of museum exhibition.29 Herein lies the complexity of the historical herbarium: as a visual representation and narrative of European political subjectivity, it resides within an equally fraught institution founded on an interpretative practice that legitimises the act of collection while simultaneously authoring its own narratives of subjectivity through politically-charged curatorial practice and display. Moreover, as part of wider museum collections, objects such as herbaria "take on additional significance specifically by dint of being part of the collection" (MacDonald, "Companion" 82). In this way, museums provide a secondary process of de- and re-contextualisation for the already stripped and revalued specimens.

Natural history collection has long been supported by the private cabinet and the public museum, the latter of which has acted as the principal means of "bringing together and organising objects in order to attempt to map the world's patterns" (MacDonald, "Companion..." 84). Greater perhaps than its role in organising and mapping, however, has been the museum's role in shaping the modern nation-state. Like the herbarium, the museum has played an indispensable part in the demonstration of mastery by colonial powers through the accumulation of material culture and the encoding and dissemination of exclusionary knowledge (Golinski 98; Thomas "The Inhabited Collection" 334).30 In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, newly-founded national museums became symbols of the nation-state through their status as houses of national collections, as well as through their ability to construct knowledge and re-narrate history and, in doing so, legitimise the power of the state (Golinski 96; MacDonald, "Companion..." 85).31 Beyond their pedagogical aesthetic function, then, the role of natural history collections in the establishment of national museums confirms the status of the eighteenth-century herbarium as an aesthetic and artefactual representation of colonial mastery and as a tool of state legitimacy.

While this conclusion is interesting, it is hardly ground-breaking considering the decades of cultural critique in which museum studies has been engaged. 32 The more interesting question, then, is how the scientific aesthetic regime of eighteenth-century herbaria has worked to attribute value and construct difference in a way that supports European hegemony through exclusion. If the project of domination is employed, as Rancière writes, in the "parcelling out of the visible and invisible" (19), I argue that the herbarium as an aesthetic process and collection in fact goes a step further, making invisible the visible through exclusion. Rather than simply a process of making certain things visible, or distinguishing between what is already visible or invisible, the herbarium forces what is/was visible into invisibility through the act of exclusion.

To underscore the distinctive nature of herbarium aesthetics in perpetuating the colonial myth of European superiority, I wish here to contrast the herbarium as a botanical collection with ethnographic museum collections as explored by Henrietta Lidchi. Such ethnographic collections, and the exhibition of these collections, are made up of objects taken from non-European societies that are deemed to have cultural meaning, but whose members have traditionally been viewed as not only 'exotic,' but "'pre-literate,' 'primitive,' and 'savage'" (Lidchi 161). The cultural significations attributed to such objects are not only constructed but fluid, depending on historical context and classification systems as well as the interpretative texts that accompany an exhibition (ibid 168). Inasmuch as ethnographic displays are constructions directed by certain motivations, Lidchi argues that such exhibits must be understood as representational systems that seek veracity based on the presence of "cultural" objects. The museum appropriates and displays these objects in order to arbitrate meaning and legitimise the credibility of knowledge frameworks that are created and/or supported by the museum (ibid 178-179; 198). I do not contest Lidchi's analysis of ethnographic museum practice; rather, what interests me is the physical presence of non-European cultural objects. Looking beyond the morally questionable appropriation of such objects and their vulnerability to changing interpretations and politics, such objects nevertheless occupy space in the Western institution that is the museum, and therefore the culture from whom an object is appropriated and which the object represents is given at least a marginal degree of visibility and acknowledgement.33 Such ethnographic items, by the very fact of being constructed by the non-European communities that are the subject of a given exhibition, bear the markings of their culture. In contrast, the herbarium is a collection of botanical specimens that have been stripped of any non-European cultural significance, without which they bear no mark of their cultural and ecological heritage. Constructed with the intention of representing a system of universalised nature that is exempt from specific physical, cultural, or political contexts, the herbarium excludes more information than it includes, thereby leaving us to wonder what, indeed, is missing. ...

Footnotes

- It is important to note that the motivations and consequences of the colonialist projects are varied and complex; however, this paper focuses on the ways in which a politics of exclusion is expressed in the aesthetic regime of the eighteenth-century herbarium, resulting in a subtle, overlooked form of indigenous erasure. For a more wide-ranging look at the motivations of colonialism, see Dening 1996. ↩

- See, for example, Stuart Hall 1997. ↩

- See, for example, Adorno 1997; Benjamin 1999; Baudrillard 1993, Bourdieu 2010; Jacques Rancière 2004; Ben Highmore 2011; ↩

- See, for example, Lisa Overholtzer and Cynthia Robin 2015. ↩

- Contemporary botanist J.R. Massey refers to the herbarium as "a special kind of museum" or "data bank" (1974), drawing attention to the dual role played by such collections as tools of both historical and current scientific research. ↩

- See, for example, Beinart and Hughes 2007; Drayton 2000; Grove 1995; Jardine, Secord and Spary 1996; Pratt 1992; Spary 2000; Schiebinger and Swan 2005. As Schiebinger and Swan succinctly state, "botany both facilitated and profited from colonialism and long-distance trade ... the development of botany and Europe's commercial and territorial expansion are closely associated developments" (3). ↩

- Linnaeus's classification system was based on the fundamental notion that all organisms reproduce sexually. He designed a method to classify plants based on a set of distinctive characteristics of plants' reproductive systems; in doing so, he created a taxonomical hierarchy that is still in use today, although it has been expanded to accommodate growing numbers of species. Binomial nomenclature was introduced by Linnaeus to formally classify and name organisms according to their genus and species in a universally-applicable way that was easily incorporated into his taxonomical hierarchy and avoided inferring bias about the quality or value of the species being named (Muller-Wille, "Carolus Linnaeus"). ↩

- Polynomial taxonomy was standard throughout the early modern period and up to the mid-1700s, when Carl Linnaeus (1707-1778) published Species Plantarum in which he proposed a binomial taxonomical system. Although Linnaeus was not the first person to work towards a more concise naming system, his publication is considered a turning point for the universal adoption of binomial nomenclature. Whereas the purpose of older polynomial taxonomies was to provide a Latinised label and description of a plant and its physical particularities, the binomial system adopted by Linnaeus sought simplicity and standardisation, giving each plant a generic and specific name, respectively, which could be universally applied ("Polynomial;" Müller-Wille, "Carolus Linnaeus;" Müller-Wille, "Walnuts" 34). ↩

- Based on this evolving taxonomy, Wijnands and Heniger write, "Clifford's herbarium reflects the development of generic concepts from Tournefort to Linnaeus" (130, 142), making it an historically valuable resource of significant interest to this study. Some of the changes to Clifford's herbarium are thought to have been made by Linnaeus himself, as Clifford hired him as personal physician and horticulturalist to his estate, Hartekamp, south of Haarlem in Holland. During his time under Clifford's employment, Linnaeus was requested to name and classify specimens - living and dried - according to his own taxonomical system ("Linnaeus and Hortus;" Wijnands and Heniger 130, 136). ↩

- It is important to note that herbaria were often accompanied by field notes or journals written by the collectors, although Massey notes an "unfortunate policy" of scanty field notes and lack of concern for original labels by early collectors, highlighting historical inconsistencies in this regard (Massey). Moreover, such notes that were made were often lost or destroyed during tempestuous sea voyages or terrestrial mishaps. The intrepid plant collector David Douglas, for example, had several setbacks while traveling through the Pacific Northwest, on one occasion lamenting the loss of hundreds of plant specimens as well as his "journal of occurrences, as this is what can never be replaced" (qtd in Nisbet 268) after having his canoe dashed to pieces in river rapids. Many field notes and journals, too, have been simply lost to history and, even if they do survive, they are not necessarily displayed or made available alongside an historical herbarium collection. As part of larger collections, herbarium specimens draw interest as much for their aesthetic qualities as for their scientific usefulness, making accompanying field notes or reference volumes to be of variable interest depending on the audience. In light of this inconsistent availability or display of field or reference notes, this paper does not consider them to be of significant value to an analysis of the aesthetics qualities of herbaria. ↩

- As Highmore notes, "The mindful and creaturely body is empiricism's first and only analytic instrument," yet because the human being is both individualistic and changing in its perceptions and passions, "the productivity of this instrument is guaranteed by precisely that which might lead you to wonder about its reliability" (26). ↩

- Highmore writes that, "Creativity, [Raymond] Williams makes clear, is not some special realm of sensitivity and expression, but the daily business of making sense of the world around us, of reflecting on it, of narrating it and communicating to others" (7). ↩

- As Highmore writes, "Taste mattered because our pleasure and inclination could so easily direct us towards the 'bad', the unworthy, the evil" (10). ↩

- "Hearsay is excluded, that goes without saying; but so are taste and smell, because their lack of certainty and their variability render impossible any analysis into distinct elements that could be universally acceptable" (Foucault 132). ↩

- Indeed, Hume applied his own emphasis on repeated and repeatable empirical verification for the discernment of taste more generally to all "nonmathematical facts" (Harris 9), under which category both human nature and natural history resided. ↩

- Highmore writes that "[i]n this way aesthetics (as an arena where experience and expression necessarily meet) becomes the living cultural expression of experience that is also constitutive of experience" (42). ↩

- Aesthetics is always political, for "The arts only ever lend to projects of domination or emancipation" (ibid 19), while at the core of politics is necessarily an aesthetics: both control, limit, and manage social divisions (Rancière 3,12-13). ↩

- Latin was the lingua franca of eighteenth-century science, as well as being considered more widely as an elite language within Europe. As such, the use of Latinised plant names would have had the effect of excluding Europeans uninitiated in the language from fully participating in this developing scientific knowledge system. ↩

- In his seminal 1987 book Science in Action, Latour equates eighteenth-century voyages of exploration to attempts to possess new regions in the sense of possessing knowledge of those regions. Explorers, he writes, are not interested in the place they are exploring so much as they are interested in bringing the place back, first to their ship and then to the power(s) that sent them (Science 217). ↩

- This supports Foucault's understanding of the relationship between knowledge formation and the increase of power as a circular, reinforcing process (Foucault, Discipline 224). ↩

- As Timothy Mitchell puts it, the world set up "as a picture" (220). ↩

- Fittingly, Linnaeus himself conceptualised his taxonomic order as a 'map of nature' (Gascoigne, "Joseph Banks" 167); and, as Latour succinctly writes, "the history of science is in large part the history of the mobilisation of anything that can be made to move and shipped back home for this universal census" (Science 225). ↩

- Although natural historical plates were in some ways more stable, a lack of standardised conventions governing the balance between design aesthetics and factual fidelity made them problematic (Miller 23-24). ↩

- Meanwhile, as Beth Fowkes-Tobin writes, the kind of knowledge that can "circulate shorn of specifics and locale became valorised for being 'scientific' and universal" (26). ↩

- Following Linnaeus's own guidelines, the herbarium, "better than any picture, and necessary for every botanist" (Philosophia Botanica 18) requires that each specimen be given its own page, and that after pressing and drying a plant in such a way that the various parts are evenly spread out, it should be arranged "methodically" and glued onto a folio sheet. The classification should be limited to genus and species, with any additional explanation written on the back (Linnaeus, Philosophia Botanica 18). ↩

- It was not until fairly recently, in fact, that weeds and cultivated plants have begun to be worthy of inclusion (Massey), which has proved invaluable in the study of so-called "invasive" species. For more on the language of weeds and invasive species, see my forthcoming article, "Crisis of Invasion: Militaristic Language and the Legitimization of Identity and Place." InVisible Culture 28 Contending with Crisis, Spring 2018. ↩

- "In this sense," he writes, "all objects that are possessed submit to the same abstractive operation and participate in a mutual relationship in so far as they each refer back to the subject" (7). ↩

- Through a narcissistic projection, Baudrillard writes, "it is invariably oneself that one collects" (12). ↩

- Drawing an instructive and apropos parallel between science and public exhibition, Sharon MacDonald writes that "Exhibitions tend to be presented to the public rather as do scientific facts: as unequivocal statements, rather than as the outcome of particular processes and contexts" ("Politics" 2). ↩

- Golinski writes that museums "encode and shape particular configurations of knowledge; they display objects but they are never simply windows to the world beyond" (98). However, Thomas goes further, arguing that the museum collection is "made out of insecure narratives, principles of inclusion and exclusion, and forms of order and affiliation" ("The Inhabited Collection" 334). ↩

- Prominent natural historians of the period played a significant role in building these collections, often donating large portions of their own private collections to fledgling institutions. Most notably, Sir Hans Sloane and Joseph Banks were both instrumental in building the natural history collections at the British Museum. In his will, Sloane allowed his private collections to be purchased significantly under value by the state after his death, these forming the basis, or "founding core" of the British Museum at its opening in 1759; and Banks acted as trustee to the Museum during his lifetime, subsequently bequeathing upon death his entire herbarium and library ("About;" Chambers xiv-1). Both collections are still extant and reside in the Natural History Museum, London, United Kingdom. ↩

- However, there has been significant push-back regarding the legitimacy of classificatory systems used to organize collections, as well as the practice and pedagogical role of collections in museums. Various attempts to question the impartiality and objectivity of collection and display, and the legitimacy of the museum in its role as authenticator and valuator have been gaining currency since the 1970s (MacDonald, "Companion..." 92). The museum as a representational system of cultural meaning-making has been extensively explored, too, by prominent cultural theorists such as Stuart Hall, who have argued that meaning is produced or constructed, rather than found, through various forms of language (Hall 4-5). For this reason, the classification, categorization, and representation of various cultures by museum curators has become a subject of great debate, and a general consensus has been reached among cultural theorists that, at the very least, "Museums do not simply issue objective descriptions or form logical assemblages; they generate representations and attribute value and meaning in line with certain perspectives or classificatory schemas which are historically specific" (Lidchi 160). This statement can easily extend beyond the museum to the already-extant collections they house, for herbarium collections most certainly employ a classificatory scheme that is historically specific; therefore, again we see that a body of work (the herbarium) that is already impregnated with the cultural, social, and political values of its maker resides in an institution (the museum) that is ruled by its own sensual pedagogy and aesthetic regime. ↩

- To be clear, there are a plethora of problematic ways in which ethnographic objects are stripped of meaningful context. In a study of engraved illustrations of ethnographic artefacts from Cook's voyages, for example, Nicholas Thomas makes clear that the manner in which the objects are represented abstracts them from their human uses and purposes, problematically placing them at "a severe remove" from the ordinary flow of experience ("Licensed Curiosity 120). Similarly, the Royal Museum of Victoria, BC, Canada houses a collection of Pacific Northwest Indigenous ceremonial masks, carefully mounted on a darkly painted wall in a darkened gallery in what Janet Berlo et al. call an arbitrary "formal, aesthetic and intellectual" template that privileges the "sense of sight over other modes of knowing" (6). Designed, it would seem, to evoke fear while educating the audience, the masks are backlit in random succession while a narrator competes with a soundtrack of indigenous drumming to explain what each mask supposedly represents. Other examples abound, even in this age of post-colonial critique. ↩