Connecting collections and collecting connections: Reconstructing the life of Mrs Edith Coleman

by DANIELLE CLODE

- View Danielle Clode's Biography

Danielle Clode is a natural history writer and academic at Flinders University, Adelaide.

Connecting collections and collecting connections: Reconstructing the life of Mrs Edith Coleman

Danielle Clode

When, owing to contortion or careless pressing, important characters are lost, they may be revived by boiling the specimens for a few moments. The segments, absorbing moisture, resume their original shape. The flowers may then be floated out, and examined under a lens. - Edith Coleman 1934 (8)

In 1934, Edith Coleman celebrated the opening of the new National Herbarium of Victoria with an article for The Argus newspaper. Edith hoped that the 'handsome, dignified exterior of the building will encourage a better acquaintance with its contents' as more than just 'a vegetable mortuary, in which, in paper cerements, thousands of flowers that once brightened the earth and scented the summer air lay awaiting inevitable decay.'

As a plant collector herself, Edith Coleman knew well the value of the plants stored in the herbaria: for botany, biogeography, taxonomy, and agriculture. Even after centuries, these dried specimens 'tell their stories as clearly as on the day they were pressed. They really are plant biographies.'

And yet, these specimens do more than record the biographies of plants. They also record the biographies of their collectors, revealing hidden or lost aspects of their lives, friendships and connections. These herbaria store not just isolated sightings of rare, little known or forgotten species, but also fragments of the lives of their collectors that may otherwise have been lost or forgotten.

The researching of Edith's biography has required many different approaches - genealogical research of her family history, archival research, compilation of her published works, literary analysis of her writing, scientific analysis of her biological work, location research and interviews with family members (Clode 2018). This essay traces just one of the many research methodologies that have made up the process of writing Edith Coleman's biography - following the trail of her specimens scattered across Australian herbaria.

Edith Coleman is known to experts in pollination and orchids for her work on pseudocopulation - the phenomenon whereby orchids entice male wasps to pollinate them by mimicking sexually receptive female wasps. Her work, along with that of the English and French amateur botanists, Colonel Masters Johnson Godfery and Maurice-Alexandre Pouyanne, resolved a long-standing mystery of orchid pollination that had confounded even Charles Darwin (Double 8-16).

From the 1930-50s Edith Coleman was one of 'our foremost women naturalists'. ('Mainly about people' 10) She was a writer who 'needed no introduction' (Your Garden 28). Her local colleagues compared her work to that of Darwin (Rupp 15 March 1933) and international experts, like Professor Oakes Ames of Harvard offered unreserved praise:

Nothing I have done in reviewing the literature of pseudocopulation would take even a breath of wind out of your sails. So far as I am concerned you are to windward of me, and my little orchidological boat is becalmed by your magnificent biological canvas. I say this in all sincerity, because you have made a substantial contribution to the world's story of knowledge. (Ames, 12 October 1937)

Edith was the first woman to be awarded the Australian Natural History Medallion for her work in 1949. Over her 30 year career she published over 350 popular and scientific articles, in the Age, the Argus and various magazines, as well as journals like the Victorian Naturalist.

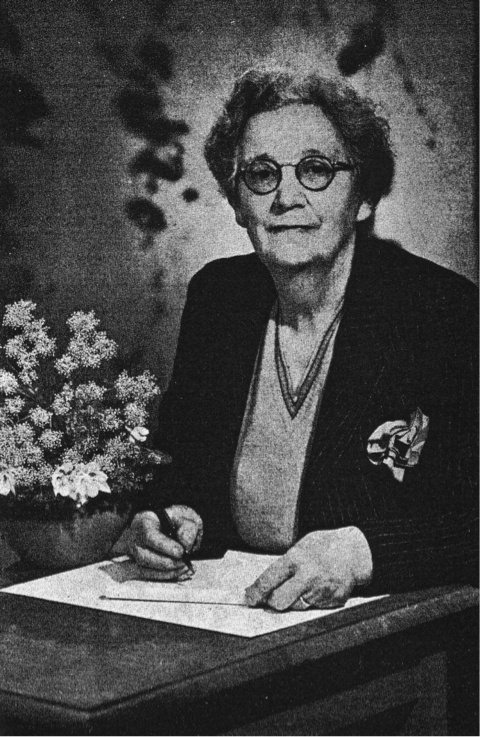

Mrs Edith Coleman, 1950 (Source: D. Coleman, Victorian Naturalist)

Today, few people have heard of Mrs Edith Coleman. Despite her prolific output, Edith is much less well-known than her contemporary Australian nature writers and naturalists like Donald Macdonald or Alec Chisholm. When I first started researching her life, I had little more than an entry in the Australian Dictionary of Biography (McEvey) and an obituary in the Victorian Naturalist (Galbraith 46). There have been few other references to her in other secondary literature at all (Clode 2005).

Edith's career as a naturalist and nature writer began at the age of 47, on the evening of the 11th of September 1922. In the halls of the Royal Society, Edith presented her first paper, on temperate orchids of autumn, to the Field Naturalist's Society of Victoria. The paper was subsequently published in the Victorian Naturalist (Coleman 1922). It is a mature, confident, accomplished work of two and a half thousand words. Her writing is accessible and engaging, yet effortlessly authoritative, strewn with the poetic phrases of Browning and Burns, Swinburne and Shelley. She invites the reader to join her on her rambles through the Australian bush, guiding and informing her audience about the treasures they might not otherwise notice. For the next 30 years, Edith would produce an average of five papers per year for the Victorian Naturalist on a wide variety of topics - from orchid pollination to echidna hibernation. Within just seven years, her work on orchids will be internationally recognised.

There is nothing obvious from Edith's past that would predict her sudden and rather spectacular transformation from suburban housewife and mother into an internationally renowned naturalist and writer. She had emigrated from England at the age of 13 and had no academic training other than teaching. Her father was a builder with a love of nature, her mother was a 'nurse child' with an unexpected love of literature (Baker 15). She married the pioneering motoring enthusiast James George Coleman, had two daughters, Dorothy and Gladys, and moved to a large garden block in Blackburn in outer suburban Melbourne.

I could find little evidence of Edith's involvement in writing or nature study before the age of 47, when she joined the Field Naturalists. I assume, conventionally, that she had been prevented from pursuing these activities because of her domestic duties - that the pram in the hall has been the enemy of good art. Edith began her career just as her own two daughters set out on their own - studying at Melbourne University. Freed from domesticity, perhaps, she was able to finally pursue her own interests.

Like most nature writers of her era, Edith hardly mentioned herself, or her family, directly in her writing. She used the personal pronoun rarely, mostly disguised in the ambiguous plural 'we'. Like most English and Australian nature writers of the time, she wrote with the 'eye' not the 'I'. Her subject was explicitly, almost exclusively, nature for its own sake. Several articles are written from different places in her travels but her focus was so firmly located on the landscape in front of her, that it is sometimes difficult picture the author at all. Edith's own words often feel like a barrier that stops me from seeing her, forcing me to look only where she has directed my gaze.

There are occasional references to her daughters and husband, but they are often oblique and easy to miss. In a rare, non-natural history article on early motoring in Victoria, Edith mentions the three founders of the RACV: Mr Syd Day, Mr Harry James and a third unnamed originator of whom "I could say some find things if space permitted' (Coleman 1931 8). The third member of this trio, was her husband, James Coleman (Priestly 2). The only 'James' she mentions by name are long-dead kings, politicians and poets.

James was reported to be entirely supportive of Edith's work, but there is no evidence that he had any direct interest in it. He had his motoring interests and Edith had her natural history interests. According to family history, they shared an interest in gardening, albeit with very different approaches. James kept the garden in order with an impeccably sharp scythe. Edith loved her 'garden wilderness'.

Other members of the household stand for law and order, even in a garden, but no mother grieved more over the loss of her baby boy's curls than I over the shorn tendrils of my truant border plants. (Coleman 1929 3)

Edith is far from alone in omitting her spouse from her work. E. J. Banfield famously neglected to mention the presence of his wife, Bertha, in his reminiscences of his 23 year seclusion on Dunk Island. Donald Macdonald hardly mentions his wife Jessie and daughter in his writing either (Griffiths 356). Their focus is on the external, not the personal.

In searching for precursors to Edith's work, I come across reference to an article published in 1920 - two years before her appearance in the Victorian Naturalist.

The Gum Tree for December contains a chatty article by Miss Edith Coleman (sic), of Blackburn, entitled "Forest Orchids," in which a number of our orchids are briefly described. (February 21 1921)

The paper does not change my impression of Edith's writing, or development (Coleman 1920 5-8). It is as well-developed as any of her later papers. But it is notable for being illustrated by her daughters, Gladys and Dorothy. Dorothy was a skilled artist who would go on to pursue a successful art business as the inventor of Nucraft modelling clay in later life (Whitford-Hazel).

Edith sometimes mentions 'her daughter' in her articles, noticing some biological curiosity or accompanying her on a collecting trip. I assume these refer to Dorothy, who was well known for having assisted her mother in her work.

Her [Edith's] own amazing achievements can hardly be considered apart from the sympathetic collaboration of her daughter, Miss Dorothy Coleman; indeed many of the best articles are the result of joint effort, the younger lady embellishing them with life-like sketches or confirmatory observations. (Willis 99)

But sometimes the daughter seems to be Gladys, discussing galls on trees with an expert at Sydney University or observing birds in her Eltham garden. Gladys was a skilled scientific and botanical illustrator (Playne 232-3). She studied botany at University and supported her family through nature writing for the newspapers. By 1924 she was writing a semi-regular column for the local Blackburn Leader newspaper called 'Sketches from the Bush'. After her marriage and move to Sydney, she wrote a weekly column for seven years, for the Sydney Mail called 'Little Glimpses of Wildlife'.

I had assumed that Edith's daughters followed their mother's interests, but now I'm not sure. This early involvement suggests a more reciprocal interest. Perhaps her daughters facilitated, rather than hindered, their mother's natural history interests?

Edith must have had a large collection of pressed plants. She supplied and received collections across Australia and the world within her network of correspondents. She was renowned for her generosity in providing material for others. Reverend H. M. R. Rupp was only one of her regular correspondents and by 1926 she was writing to him 'pretty much every week'. Rupp was impressed by Edith's dedication.

'She, I think, sends me more specimens, living and pressed, than any other correspondent I have - and that is saying a good deal,' he said (Rupp 4 March 1927).

Edith frequently comments on the techniques of posting, pressing and preserving orchids. She stresses the importance of fresh specimens, carefully pressed.

The orchids should be picked quite fresh, and if packed in layers in a cardboard or tin box, between layers of wet paper or moss, and the air excluded, they will carry quite well to the other side of Australia. ('Collecting Orchids' 47)

Edith required no fancy technical equipment is required. She obtained her best results 'under two weighty books, Ben Jonson and Dante's Inferno, illustrated by Dore' (Coleman 1934 8).

Even though Edith knew that characteristics used by plant taxonomists are not lost in drying or pressing, she was always searching for better ways of preserving her specimens. She was an enthusiastic photographer, first with a No 1. Box Brownie and later with a Thornton Pickard ¼ plate camera. She tried other techniques too. In 1932, Edith wrote to fellow collector, Rica Erickson:

I have little jars, all labelled, many of them with your name - in which I have preserved a specimen or two of such as have reached me in a living state. These are in a 10% solution of formalin and show every part. These too, someday, will go to the Herbarium. (Coleman 10 April 1932)

There is no record of Edith's personal collection being lodged with the National Herbarium of Victoria after her death, nor any other public collection. I suspect that her research materials were distributed to colleagues in the Field Naturalist's Club of Victoria. Her specimens are scattered, in herbaria across Australia, most likely as part of other people's collections, like Rupp in NSW, Rogers in South Australia or Erickson in Western Australia.

I find just over two thousand specimens collected by someone called Coleman in the Virtual Herbarium database, which provides online access to the collection of Australian herbaria. I scan through and delete all the ones with the wrong initials, from countries Edith never visited, those outside her lifespan. I am left with two hundred and thirty eight specimens which might be hers. Most, but not all, are designated as Mrs Coleman, E. Coleman or Edith Coleman. They range from 1904 to 1949 but over 90% were collected in the 1920s, half in 1926 alone. The vast majority are orchids. And most are collected around Melbourne - particular near the three areas where Edith lived and holidayed: Blackburn, Healesville and Sorrento. The broad contours of this map match perfectly with those of Edith's published articles, tracing the peak and swell of her interest in orchids. There are few outliers, nothing unusual or revealing.

There are a handful of Coleman specimens collected near Saddleworth near the Flinders Ranges. Some are by Mr Coleman, others by local farmer, Frederick Coleman. One is by D. Coleman. I speculate that Frederick is a relative that Dorothy is visiting even though I don't think James had other family in Australia. Closer inspection reveals that the D. in the database is [D.] which means the initial is assumed. The specimens are all agricultural weeds more likely, then, to have been sent in by a farmer.

Others are out of place, but I can't entirely rule them out. In 1925, there is a specimens of mulga oats, a native grass, collected from the Dromedary Hills of inland Western Australia. The database provides co-ordinates - longitude and latitude for the collection site - with reassuring precision.

And yet I know this apparent precision is misleading. The original collectors did not have GPS co-ordinates. The numbers are simply derived from whatever information was recorded with the specimens - perhaps only a general place name. They are approximations at best for older specimens. X very often marks the centre of a radius, rather than the spot itself. But databases don't deal in approximations. They turn best guesses into absolutes.

The Dromedary Hills are in the middle of nowhere. There is barely a trace of human occupation on this landscape for miles in all directions. Surely this is another false lead. And yet the record is for E. Coleman. She did travel regularly to Western Australia, and her brother Hervey held a mining lease at Gwalia, south of Leonora in 1909 before moving to Geraldton. The Dromedary Hills lie 500km in each direction between these two locations.

I find one greenhood orchid in the Australian National Herbarium collected simply from 'The Look-out'. The database has no co-ordinates for this: no country, no state, no region, no local government area. But I recognise the date, the place and the species. The details are the same as an orchid collected from 'The Look-out' at Wilson's Promontory by Edith in 1926, which is in the Adelaide Herbarium. The Canberra herbarium has no record of how this specimen came to be in their collection. Perhaps it was a gift from another institution.

Two specimens in the Tasmanian Herbarium belonged to Florence Perrin, a local seaweed specialist.1 They illustrate the complex path such specimens take to their final resting place. One of them is labelled 'Herbarium of Australasian Orchids (R.S.Rogers)' with the collector handwritten as 'Mrs Coleman'. A transaction in at least four parts.

I realise now how personal collections are broken up, distributed, swapped and exchanged. The botanist is a minor detail, the act of collecting merely a servant to the shared body of public knowledge it contributes to. Specimens are stored in vast racks of plastic trays - sorted by species, not by collector. Details of the collector might be reduced to a scrawled name on a label or even only be identifiable by skilled analysis of handwriting or characteristic styles of specimen preparation. Natural history collections are intentionally biocentric.

The historical context of human activity is secondary in science. When collections are digitised their associated data are tested, analysed, consolidated and parsed to ensure rigorous standards of quality. There is no room for uncertainty in this recoding. Data is either accepted and included, or rejected. Yes or no, 0 or 1. But much information is lost in the process: the ephemeral, the suggestive and the possible. What was once an uncertainty becomes solidified into an error, replicated and repeated like a mutation through generations.

Edith's orchid specimens are proving capricious and ephemeral, fragments that flicker in and out of other people's archives.

The earliest four Coleman specimens I can confidently identify are all orchids. The two leek orchids Prasophyllum odoratum and Prasophyllum patens were collected from the Yarra Ranges in November 1920. The next year, in July, two helmet orchids Corybas aconitiflorus and Anzybas unguiculatus were collected, again in the Yarra Ranges, near Healesville, where the Colemans owned a cottage. These specimens are part of the Rogers Collection, preserved in the State Herbarium of South Australia. But the specimens were not collected Edith. They were collected by her eldest daughter Dorothy.

Dorothy was 20 at the time she sent in those first orchids, but this was not her first foray into natural history. She had joined the FNCV as a junior member at the age of 14 and regularly attended events there. She, and her sister Gladys, maintained a regular correspondence with Donald Macdonald in his newspaper column 'for boys' between 1913 and 1917. Their letters reveal knowledgeable, confident young women with a keen environmental awareness and enthusiasm for conservation, the outdoors and ethical treatment of animals.

If Edith's career began when she joined the Field Naturalist's Club in 1922, she was preceded by her daughter by some nine years.

In October of 1921, Edith collects the first specimens which will ultimately find their way into the State Herbarium of South Australia. She is recorded variously as "Edith Coleman" or "Mrs Coleman". The specimens are again all orchids, Caladenias and Prasphyllum leek orchids. They have been sent to Dr Richard S. Rogers, who remains a long-standing family friend.

I arrange a time to visit the State Herbarium, located on the edge of the Botanic Gardens in the parklands surrounding the city of Adelaide. The Herbarium is more than just a collection of pressed plants, important though that is. It is also an archive, of books, letters, photos, articles and miscellaneous artefacts.

Dr. Rogers was a well-known Adelaide figure in the medical establishment - a 'doctor-soldier and forensic pathologist who described 82 new orchid species (66 from Australia)' (Pearn 52-4). He left his archives to the University of Adelaide, who retained the medical material and transferred the botanical material to the Herbarium, along with his orchid notebooks, photographs, correspondence and artefacts, all minimally catalogued. The curator seeks out the relevant boxes for me, placing them on a large table in the library, alongside trolleys loaded with neatly numbered notebooks. It is testimony to Roger's original orderliness that the collection is so easy to navigate. Everything is in alphabetical order, much as he left it, clearly labelled and indexed, with page numbers. Rica Erickson's notebooks in the State Library of Western Australia are just like this too, organised by date or taxonomy, filled with small, neat handwriting and exquisitely labelled illustrations. I imagine Edith's 'busyness' room filled with similar materials, inscribed with her scrawling rounded handwriting, pages overflowing with notes in preparation.

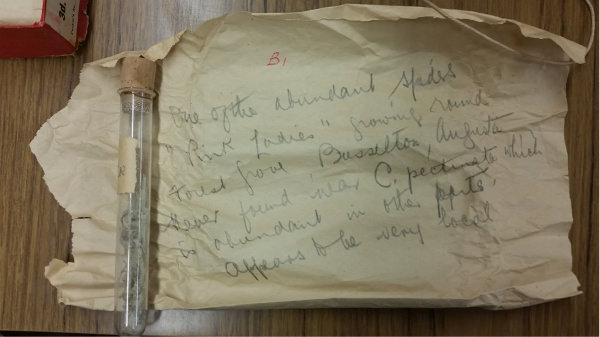

One of Edith's tube specimens from the Rogers Collection, Adelaide Herbarium

A pile of cylinders, roughly wrapped in paper, unroll to reveal glass test tubes stoppered with cork. The glass is frosted grey, like the desiccated material within, the 10% formalin solution that protected them long since evaporated. The orchid within looks like a curled-up huntsman spider (another of Edith's favourite topics). These are Edith's specimens of 'fresh tissue'. Her handwriting scrawls collection notes on the inside of the paper. They remind me of that motif so often used in time travel stories - a flower from the past, perfectly preserved in an airtight glass capsule, only for the past to suddenly catch up with it, withering before our eyes.

I turn the tube in my hand, imagining that I might magically revive the plant inside, as Edith had once suggested, by boiling it. But even if that were possible, I am sure it would only transform for a moment before, like the flower from the past, disintegrating - lost as soon as it was found.

The pressed specimens have preserved better. The curator retrieves the specimens that Edith sent Rogers in 1921, gently unfolding the sheets of card that surround them. The leek orchid has long lost its lilac-lavender hue, faded to a yellowed sepia. It was a new species and Rogers named it Prasophyllum colemanae. It's listed as P. colemaniae in the Atlas of Living Australia. It has only ever been collected by Edith, twice in 1921 from Ringwood and Bayswater and once in 1930 from Anglesea. It is presumed to be extinct - a species lost almost as soon as it was discovered.

I assume Rogers named the species after Edith, but the curator points out it should be called colemanarium, because it is named after the Colemans plural, not Coleman singular. In his paper describing the new species Rogers writes:

Named in honour of Mrs Coleman and her daughters, enthusiastic collectors of orchids in Victoria. (Rogers 337)

Not just Edith, not just Edith and Dorothy, but both daughters: Gladys as well.

This family connection makes me realise that I should be searching for all the Colemans, not just Edith. I find 24 specimens collected by Dorothy, nearly all from the Healesville area, a few from Sorrento and Wilson's Promontory. I find specimens collected by Gladys Coleman from north Queensland, where she was travelling with her husband, anthropologist Donald Thomson. I re-search under her married name and find six more specimens, including several fungi. One of them is the tropical epiphytic orchid Chiloschista phyllorhiza collected from Cape York. Gladys sent it to Dr Rogers in October 1933, perhaps too early to help him resolve the taxonomic dilemma he outlined in a paper on the subject, published in December.

More surprising still though, are nineteen specimens collected by a 'J. G. Coleman' from 1923-1926. They are all orchids. They all come from the same places as Edith's collections. They are all collected in the peak period of Edith's collecting interests. It cannot be a coincidence.

This is the only suggestion I have that James directly participating in Edith's natural history work, other than gardening. The specimens are lodged in the National Herbarium of NSW. The database records don't indicate how they got there. I wonder if they were sent to H. M. R. Rupp, who left his orchid collection to the NSW herbarium.

Two of the specimens are from Wilson's Promontory, collected in September of 1926. They are both slender greenhoods, Pterostylis foliata. Edith described this collecting trip for the Victorian Naturalist:

'A party of four (Dr. and Mrs. R. S. Rogers, of Adelaide, my daughter and myself), spent an interesting week at the National Park, Wilson's Promontory, early in September.' (Coleman 1926 211)

Surely Edith would have counted James if he had been in this party? It is a strange and unlikely omission. The database reveals nothing further. I will have to go to Sydney to see the source material myself if I am to answer this mystery.

Generous curators retrieve the specimens from their individual trays. Most of the specimens have indeed come from Rupp. Each sheet, with its delicately pressed plant, contains a series of annotations, snippets of paper glued to the page in different hands and typeface, from different times. One contains a browned strip, cut from Rupp's original collection which records, in his handwriting, the collector as 'Mrs. J. G. Coleman'. A later typed label reduces the name simply to 'J. G. Coleman'. The source of the error seems clear. It is a mistranscription. I am reminded of the adage I learnt early in my career about data entry - 'rubbish in; rubbish out'. Of all the specimens we can locate, all can be attributed to Mrs not Mr Coleman.

Occasionally a specimen also includes a note by Edith herself. She never refers to herself as 'Mrs. J. G. Coleman' in these notes. I can't recall her doing so elsewhere either in her writing or letters. It is Rupp who refers to her by her husband's name. It is Rupp who has created this erasure of her identity, this potential confusion of her work with that of her husband.

I am reminded of a comment the geologist Charles Lyell once made of the mathematician Mary Somerville:

Had our friend Mrs. Somerville been married to La Place or some mathematician we should never have heard of her work. She would have merged it in her husband's and passed it off as his. (Alic 190)

Such was the fate of Edith's own daughter Gladys, whose early work is largely combined into the collections and work of her more famous husband Donald Thomson.

But Rupp seems to have been aware of his error. On several sheets, in a different pen, he has added 'Edith' in brackets above J. G. On others he goes further, scraping away both the initials and the addendum and reinscribing Edith as her first name. The erasure of Edith's identity has itself been erased. She is reinstated in her own right.

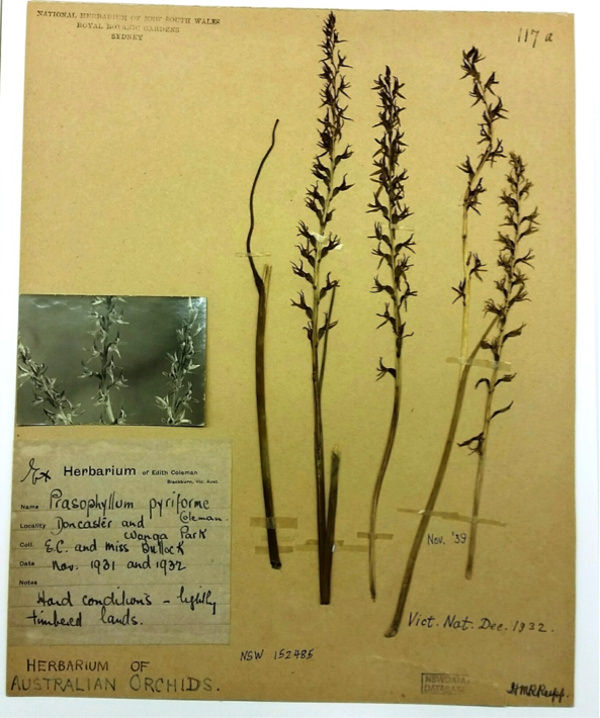

The type specimen for Prasophyllum pyriforme, from Edith's personal herbarium

For the first time in all my research, I find a sheet that comes directly from the pages of Edith's own herbarium. It is contained in an orange folder to designate that it is the type specimen for the leek orchid Prasophyllum pyriforme. This is the specimen against which all other specimens of this species are compared, the specimen that defines the species. It is a species that Edith herself discovered and described, in Latin, in 1932. Scrupulous as ever, she acknowledges her co-collector as Miss. F. Bullock (Coleman 1932 195).

Edith died on the 3rd of June 1951. On June the 12th, the Field Naturalist's Club held their annual general meeting, where her specimens are still held today. Despite bad weather, the 80 members in attendance observed a minute's silence, fittingly, in the rooms of the National Herbarium.

'She will be sorely missed,' Rupp concluded in his obituary, 'but her work has a place in that great fabric of scientific truth which is slowly being built up through the years and it shall not perish' (Rupp 1952 122).

In pursuing the life of Edith Coleman I have, perhaps unintentionally, followed the same path as many other biographers of women before me. As a writer, I sought my models in nature writing rather than feminist biography, in Robert Macfarlane's Landmarks, Helen Macdonald's H is for Hawk, The Story of My Heart as rediscovered by Brooke and Terry Tempest Williams and recent biographies of Australian plant collector Georgiana Molloy. And yet, in attempting to reconstruct the life of a forgotten or neglected female naturalist, I have inevitably employed the genre of biography to enact a feminist revision (or correction) of history. As such this project faces all of the typical challenges to restoring women's history - the loss of records and archives, absence of commentary and critical appraisal, the multi-stranded nature of women's lives and questions over the value of woman's work. A biography of a woman by a woman is not necessarily a feminist work (Caine 247), but I find my work has many of the elements of a feminist biography identified by Mary Mason (Stanley 58).

Fragmentary biographies may demand a greater level of creativity in their construction, placing greater demands on the author to bring themselves into the story. Autobiographical elements intertwine with the biographical (Alpern et al. 3). I have found that my subject's life and story has profound relevance to my own. I've realised that the precision and fine resolution of biography captures details missing in broader historical analyses, from which women's lives have already gone unrecorded or been erased from the record. As others have found before me, closer inspection of one woman's life reveals a more richly complex intertwined set of relationships between public and private lives than traditional biographies of national 'heroes' or men of achievement (Alpern et al. 6).

And yet this is also a scientist's biography, a subgenre with its own unique challenges (Shortland and Yeo), not least of which is the separation of the intellectual from the personal and emotional. The particular taxonomic thread explored in this essay may appear to be more scientific and intellectual than others, and yet it nonetheless reveals the tenacity and perspicacity of Edith's character, the complexity of the social environment she lived in and the richness of the connections she built, within her family and among her colleagues. It was a Latin suffix that convinced me that my conventional assumptions about motherhood and writing were probably wrong. Even the most scientific of data contains an emotional history if we know how to read it. Edith Coleman the international expert in orchid pollination was an extraordinary scientist, but close examination of her entire life - her life cycle - reveals a great deal more.

In 2011, a lilac leek orchid was photographed in Gippsland. It was the first time anyone had identified Prasophyllum colemanarium since the specimens Edith had collected from different sites around Melbourne. And yet here it is, eighty years later and 120kms east, rescued from extinction and restored to life. Such disappearances and reappearances are not uncommon among rare species, particularly in this age of mass extinction and ecological catastrophe. It reminds me how transient and ephemeral, yet resilient, orchids can be in life - difficult to find, complicated to understand and hard to classify.

Just like their collectors.

Works cited

Alic, Margaret. Hypatia's Heritage: a history of women in science from antiquity to the late nineteenth century, London: Woman's Press, 1986. Print.

Alpern, Sara, et al. 'Introduction.' The Challenge of Feminist Biography: Writing the lives of modern American women, Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992. Print.

Ames, Oakes. Letter to Edith Coleman, 12 October 1937, quoted in Baker, 13-14. Print.

Baker, Kate, Biographical sketches 'Silhouettes', Series 2. File 3 Edith Coleman (Box3-4), Papers of Kate Baker 1893-1946, MS 2022, National Library of Australia. Print.

Caine, Barbara. 'Feminist biography and feminist history', Women's History Review, 3.2 (1994): 247-261. Print.

Clode, Danielle. The Wasp and the Orchid: The remarkable life of Australian naturalist Edith Coleman, Sydney: Picador, 2018. Print.

Clode, Danielle. 'Professional and Popular Communicators: Norman Wakefield and Edith Coleman.' Victorian Naturalist, 121.6 (2005): 274-281. Print.

Coleman, Edith. 'A New Victorian Prasophyllum.' Victorian Naturalist, 49 (1932): 195. Print.

Coleman, Edith. 'Wonders of the National Herbarium: World-Famous Collection of 1,500,000 Plants.' The Argus, Saturday December 8 1934:8. Print.

Coleman, Edith [E.C.] 'Thirty Years of Motoring in Australia: A Woman Looks Back.' The Age, Saturday 1 August 1931: 8. Print.

Coleman, Edith. Letter to Rica Erickson, 10 April 1932, Rica Erickson Papers, MN 1740, ACC5448A, 8588A/4.2, State Library of Western Australia. Print.

Coleman, Edith. 'A Garden Wilderness.' The Argus, Saturday 3 August 1929: 3. Print.

Coleman, Edith. 'Forest Orchids.' The Gum Tree, vol. December, 1920, pp. 5-8. Print.

Coleman, Edith. 'Orchids at the National Park.' Victorian Naturalist, 43 (1926): 211-212. Print.

Coleman, Edith. 'Some Autumn Orchids.' Victorian Naturalist, 39 (1922): 103-108. Print.

'Collecting Orchids', Western Mail (Perth WA), May 10 1928: 47. Print.

Double, Susan. 'Beautiful Contrivances.' Orchids Australia, February 2016: 8-16. Print.

Galbraith, Jean. 'Edith Coleman: A Personal Appreciation.' Victorian Naturalist, 68 (1951): 46. Print.

Griffiths, Tom, 'The natural history of Melbourne: The culture of nature writing in Victoria, 1880-1945', Australian Historical Studies, 23.93 (1989): 339-365. Print.

'Mainly about People', The Daily News (Perth, WA), Thursday September 12 1929: 10. Print.

McEvey, Allan. 'Coleman, Edith (1874-1951).' Australian Dictionary of Biography, vol. 13, Melbourne: Melbourne University Press, 1993. Print.

Pearn, John H. 'Australian orchids and the doctors they commemorate.' Medical Journal of Australia, 198.1 (2013): 52-54. Print.

Playne, Moria R. 'The Line Drawings, Paintings and Painted Photographs of Five Women Artists.' Donald Thomson, the Man and Scholar, Ed Bruce Rigby and Nicolas Peterson, Canberra: Academy of Social Sciences in Australia, 2005. Print.

Priestley, Susan. The Crown of the Road: The Story of the RACV. Melbourne: Macmillan, 1983. Print.

Rogers, Richard S. 'Contributions to the orchidaceous flora of Australia.' Transactions and Proceedings of the Royal Society of South Australia, 47 (1923): 337-341. Print.

Rupp, H. M. R. Letter to W. H. Nicholls, 4 March 1927, Item 17, Acc No. 503.0/001, 'Papers and correspondence of Rev. H. M. R. Rupp', Box 1&2, Items 13-31, National Herbarium of New South Wales Library. Print.

Rupp, H. M. R. Letter to Edith Coleman, 15 March 1933, quoted in Baker 13.

Rupp, H. M. R. 'In memorium - Edith Coleman.' Australian Orchid Review, 16 December 1951: 122. Print.

Shortland, Michael and Yeo, Richard. Telling lives in science: Essays on scientific biography, Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 1996. Print.

Stanley, Liz, 'Moments of writing: Is there a feminist auto/biography?' Gender and History, 2.1 (1990): 58-67. Print.

Whitford-Hazel, W. 'Australian invents new modelling medium', The Sun, reproduced in Baker 26-27. Print.

Willis, J. H. "First Lady Recipient of Natural History Medallion - Mrs Edith Coleman." Victorian Naturalist, 67 (1950): 99. Print.

Your Garden, 1 December 1947, 28. Print.

Acknowledgements

I am very grateful for the time and assistance of the following herbaria staff with the Coleman material in their collections: Juergen Kellerman and Lorrae West at the State Herbarium of South Australia, Lyn Cave from the Tasmanian Herbarium, Brendan Lepschi at the Australian National Herbarium, Kristina McColl, Miguel Garcia and Shelley James at the National Herbarium of New South Wales, and Pina Milne, Philip Bertling and Sally Stewart from the National Herbarium of Victoria.

Footnote

- HO 503143 (Prasophyllum lindleyanum, from Ringwood, Victoria) and HO 503242 (Pterostylis pedoglossa, from Black Rock, Victoria), extracted from Australia's Virtual Herbarium. Additional details provided by Lyn Cave, Registration Officer, Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery. ↩