Spatial Cycles: Notes from Working in a University Heritage Museum

by Zeny May Dy Recidoro

- View Zeny May Dy Recidoro's Biography

Zeny May Recidoro is a cultural worker based in Quezon City, Philippines.

Spatial Cycles: Notes from Working in a University Heritage Museum

Zeny May Dy Recidoro

Spatial Cycles is about the secret life of the re-purposed space of the Bulwagan ng Dangal University Heritage Museum at the University of the Philippines, Quezon City. The work will look into the its specific audience, characteristics, and its artistic and educational programming. I will respond to the spaces and communities surrounding it. Their past and current concerns and the process of transformation it has undergone, from its inception in 2009 to the present. This essay also considers the question of what constitutes 'heritage' and the shape and appearance of an 'art space' or 'museum'. It will serve as discourse to envision futures that are more open to the presentation and programming of art forms that are transitioning into transdisciplinary practices and newer media.

1. Hinges and Fringes

I began this essay at a laundromat. It was a hot afternoon and I faced the warmth of a dozen dryers. Next to me were two women who talked about urban legends; they segued into dead bodies found along avenues, wrapped in tape and with accusatory placards placed around their necks. 'Is it real?' they asked, 'what if it happens to us?'. Clothes spun inside the machines, as did the thought of imaginary bodies outlined by fabric tumbling inside in a confusion of color and awareness of non-being. One of the machines contained my clothes, objects that were also one of the many spaces where I placed my body and assumed an identity or several. Everywhere there was laundry that had to be unpacked and aired out; I had my own, and I was suffocating in mechanical heat, the smell of detergent and uncertainty.

This essay is also an airing and sorting out, an unfolding. However, I shake off any impulse to think that these things need to be put in their place, or any place. And I begin again by defining my former and current definition of heritage, and what I think constitutes it. As an undergraduate, the idea I had of 'heritage' consited of churches. This is perhaps founded upon my earliest learning experiences of local history and geography, when churches comprised a bulk of known and popular local historic sites, followed by old stone houses, bodies of water, mountains and caves; animals and plants also play a part in heritage too. Shopping malls have a special place in every clogged heart. Churches are literally and figuratively a looming presence in every Philippine town, a main feature and go-to place in every school trip and tourist itinerary. They are emphasized as spaces that all aspects of history and culture hinge upon, and are seen as structures whose colonial narratives have both enriched and cancelled national history. The extent with which the church has ingrained itself to the social body has also led to the emergence of traditions and rituals that have become indexes of memory and nostalgia. Albeit, some of these traditions and rituals emerged out of a measures response to violence and oppression. The church also functions as an ideological institution, and a panopticon with which the local response was to course expressions of identity through memory, community, and resistance. The church as a tool for surveillance is best demonstrated by the 18th century work by P. Modesto de Castro, Urbana at Felisa, in which the correspondences of two sisters, on a superficial level, outlines good manners and right conduct as defined by a colonial mindset. Taking into account context and subtext, it is also a warning of the dangers and pitfalls of an extremely righteous and impervious surveillance state. The church has extended itself not only in the spiritual and social life of communities but they have also informed and controlled the cultural, economic and political consciousness of the Philippines.

Part of my views on heritage, as structure and concept, leans upon the institutional. Things that are considered heritage persist because they are valued and managed by specific institutions, or in some cases a community or family. The necessity of institutional support, either from a private or state entity, has always been emphasized. In turn, these institutions survive based on their ability to effectively perpetuate and promote what has been considered or what has qualified, based on a set of guidelines, as heritage. There is an emphasis on the mandate of museums as a repository for objects thought to be of national importance in order to help forge a sense of national identity; for museum workers to be carers for and conservers of objects that are considered indexes and definitions of locality and identity. Art and culture are linked with history and community. Through thethe conservation of art and the preservation of heritage, and the re-telling local stories, help to ensure a continuity. Recognizing what constitutes our creative and intellectual traditions create for us a distinct way of doing things - practices that present and affirm; a public poetics that provides for the individual an identity moored in tradition and binds them in harmony with society (Cruz-Lucero, 2007). I also think of space, of cities, as moving or silent archives, in which everything that exists is an index of something else, an idea or a story that has been erased or cancelled by the last flood or demolition. In turn, the awareness of what is, what has been (lost), and what could be (recovered) can also foster an understanding of what lies beyond our own index. Considering heritage, which encompasses art and culture, and history, is a double act of narrowing and expanding horizons.

I am, however, still inclined to ask the following questions, given how the fields of culture, heritage and the arts has been largely trivialized or relegated within the boundaries of commerce and tourism: what constitutes heritage in relation to its guests and to the communities it seeks to serve or represent? From a historical standpoint, for whom were these spaces meant for? What does the effect of an adaptive re-use signify for a community and for the space itself? And beyond preconceived notions of heritage and museum space, where can we possibly locate emerging and alternative art spaces and what facets of culture and history do these spaces respond to?

When perceived as a space, the museum is somehow akin to a church as a place of sacred stillness and forbidden things (no touch, no noise, and so on). This is not, of course, a complete and direct analogy. Both places could be considered sites of silent yet palpable contentions. Local cultures have insisted and persisted in spite of cancellation or destruction; when reasoning does not suffice, there are the subtle acts of subversion and sedition that arise from the undercurrents of a text, an artwork, song or performance, a story, even in rituals and food. There also is the constant and direct engagement of those at the fringes with groups and institutions at the perceived center of Philippine society. An example of which would be how indigenous people's from the island of Mindanao will come to the metropolis to voice out their plight and educate students in state universities and colleges of their ongoing fight to reclaim their lands and lives.

2. Fist and Phantom Limb

The Santa Cruz-Carriedo area. Manila City is a mixture of commercial, residential, office, and heritage buildings. Among the buildings seen in this photo are Plaza Fair (far left), a high rise condominium (back), and the Don Roman Santos Building (center), a neo-classical building built in 1894 and expanded in 1957.

Negotiations -resistance and insistence- are imaged or performed within and beyond their premises. The threads that connect art spaces and museums to the re-purposing and re-articulation of heritage and tradition can also help arrive at a re-consideration of heritage. The motions and initiatives to restore or re-purpose a space hinges upon its significance and importance to local history and its direct relation to communities and society. In spite of my position as a local, I am still in the process of learning more deeply and holistically of local culture defined by scenes, smells, and spatial oddities. This paradigm among museums, art spaces, heritage sites and their respective public and educational programs is changing. At times, I have the tendency to think of cities or towns as museum complexes in flux or inhabited, living art spaces. Localities which contain cultural objects -may it be a piece of architecture in the form of a colonial stone house or a fragment of oral literature- are curated through better land use plans and further work on cultural mapping programs. Heritage, as spaces, structures, and features of a society's cultural landscape, can be considered not only for what they arebut for what each space has been and what it could become. To think of heritage both as structures and as an idea or ideal conjured to inspire pride or nostalgia, I inevitably find myself returning to my experiences of urban landscapes.

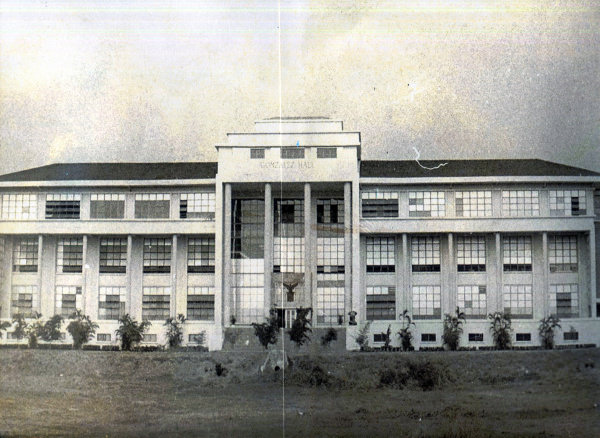

From the busy thoroughfare of the Elliptical Road and branching off from Commonwealth Avenue is the stately President's Avenue which leads to the cool shades of acacia trees along the Academic Oval of the University of the Philippines, Diliman (UPD) in Quezon City. Situated at the south-wing basement of the UP Main Library is Bulwagan ng Dangal (BnD), the university heritage museum. In English, this roughly translates to Hall of Honor. However, 'dangal' also means 'fist'; to affirm honor with the fist. The raised fist is a significant gesture specifically in UP's university culture, harking to its continuing tradition of integrating scholastic pursuits with activism. The museum's history can be connected from the inception of the Philippine educational system under American colonial rule which provided the foundations for the university's inception in 1908. Eventually, UP was envisioned by former president Manuel L. Quezon as a part of a grand civic plan for Quezon City, located some eleven kilometers from Manila City, to become the Philippines' new capital in 1939 (Milestones in History). It was also through this that UP, from its neo-colonial architecture, was shaped to become a 'modern university'. The transfer of the campus and administration of UP from Manila to Quezon City transpired in 1949; UP Manila was retained as the university's medical school, while UP Diliman became the main campus and seat of the university system's administration. UP Diliman's design was patterned after the City Beautiful ideology (Lico, Diliman: Tracing the Terrain 2) though some of its first buildings were quonset huts which had been used during the second world war and were re-purposed as homes for university faculty and employees (Gonzalez and Lico xviii).

The university plan, initially prescribed by American architects William Parsons and Harry Frost, became at once both a reflection of and a challenge to the dominant cultural ideology of the time, specifically in the promotion of this advocacy through architecture in relation to state education. During the period of the Philippines' Americanization, terms such as 'benevolent assimilation' and 'altruistic design' (Siglo 20: A Century of Design and Style in the Philippines 3) were used to promote an imperial worldview and way of life, which permeated fields in the social sciences, technology, and the humanities with the aim to transform Filipinos into potential American citizens (Lumbera 2017). While it would be right to acknowledge the benefits it has bestowed upon the Filipino cosmopolite, these practices have been effected at the expense of local culture and further deteriorated indigenous ways of life that have managed to survive through centuries of disparagement. It is often said that the university is a microcosm of society and one can get a sense of what these designs intended to be, as university narrative that corresponds to national history, from the size and breadth of the paired edifices lining the academic oval. From the seat of administration, Quezon Hall, to the site of BnD, Gonzalez Hall, also known as the Main Lib, a contrast of formal, neo-colonial structures, a meeting of green spaces and modern design mark the university's geography. Within this are also marks of a spatial pastiche belying issues on land use and increasing privatization: behind the commercial and business spaces of the UP-Ayala Techno Hub is the university's arboretum, pockets of old villages and informal settlements. And less than a kilometer away are the thoroughfares of PhilCoa, Commonwealth Avenue, and the Elliptical Road shining with the dust and fury and roar of buses, jeepneys, and cars. These rumbling avenues drag with it urban bric-a-brac: grief in a plastic bag, love notes to the oppressed, laughter and lust fermenting beneath skirts and between shorts. The noise sharply declines into the hum of suburbs -spaces which also correspond to the life and energy of the university.

The University of the Philippines Main Library in Diliman, Quezon City. Photo from the University Archives.

In the creation of a brand of university pride, specifically of its spaces forged under American colonial rule, one can also describe the structures and the entire landscape of the university as charming and 'nostalgic'. However, closer scrutiny will also reveal marks of benign, if not outright, neglect. Issues on land use and maintenance of old buildings, considered 'heritage structures', are rife within the university. In 2015 and 2016, the University's College of Arts and Sciences Alumni Association (CASAA) cafeteria, the Alumni Center, and the Faculty Center were lost to fire. In a message issued by university chancellor Dr. Michael Tan in UPDate Diliman, he states that the university is "looking mainly into compliance with several policies related to fire prevention". Another report states that "Authorities said that faulty electrical wiring could have caused the blaze". The building, which housed the departments and operation offices of the College of Arts and Letters and the College of Social Sciences and Philosophy, was seen not only as a hub of scholastic life but a repository of national and local knowledge; a quarry of collective and personal memory. Two exhibitions installed at the Bulwagan ng Dangal, recovering FC: space and memory (2016) and Re-place: Mapping the Story of FC (2017), elucidates and attempts to process the loss through a series of works that seeks to remind and to provide a measure of comfort in remembrance.

The Faculty Centre a few months after the fire of April 2016.

In relation to the museum and university spaces, an article from the Philippine Daily Inquirer cites a postgraduate study on rapid fire risk assessment by engineer Harold Aquino from the UP College of Engineering in which he states that "the Main Library has about the same fire risk level as the Faculty Center". As a response to these events and urgent matters, specifically for heritage structures such as the Main Library, academic and administrative units have made the necessary yet painfully slow steps to implement long overdue structural upgrades and improvements. As such, it seems that CASAA (College of Arts and Sciences Almuni Association cafeteria), the Alumni Center, and FC were collateral damage in what must have been a long drawn warning. More than a year later, the future of the Faculty Center is still subject to speculation. At present, the Faculty Center has been demolished and is like a phantom limb - students and jeepney drivers still refer to the now empty space by its name, 'FC'

3. Library and Cellar

The back of the Main Library looks over the Sunken Garden, an open field where students can play frisbee or soccer, and hold concerts or events. Visitors hold picnics or lounge at the grass slopes overlooking the field; children from neighboring villages and settlements also play and explore the vast campus grounds. In between these two university landmarks are a strip of trees, wild grass and bushes. From the distant sounds of cars and jeepneys rumbling past the Academic Oval, one can also hear the buzzing and bustling of a million tiny lives beneath a layer of dead leaves, debris, and trash. Here, animals are in their element. An unverified story tells that the library had been built over a large pond still accessible, it has been said, through an entryway at the back of the library. It seems plausible, as its territory had been marshland and jungle. It had also once been a stronghold in the late 19^th^ century for revolutionaries fighting against the Spanish(Milestones in History quezoncity.gov.ph), before an American university town had been transplanted over it.

The Facade of the UP Main Library at present, surrounded by thick foliage.

The interiors of the Bulwagan ng Dangal, with its permanent collection on exhibit. The artworks were donated by UP alumni and faculty, among them four National Artists for Visual Art.

I arrived at BnD in 2015, after a brief stint teaching humanities at a Catholic university. A former professor and mentor Dr. Cecilia De La Paz got in touch with me and asked if I were interested to return to museum work. This was also the time when the Philippine educational system was transitioning from a ten year elementary and secondary school program to K-12 (adding two years in high school). This meant a weaker influx of college students in universities, including the one I worked for. I was faced with uncertain prospects. In a dim hallway of the old Faculty Center I readily agreed. In considering the BnD as a structure that signifies ideals and ideas revolving around an academic and public community, requires a consideration of its geography; to see it from a distance before exploring what it is within. The roads that lead to BnD inform its history and the places that surround it supply us with a vision of its trajectory. Further, imbued within these decidedly nondescript avenues, streets and sites are histories which have also worked or 'simmered' to subsequently shape its current form and its continuous transformations, part of which is the university heritage museum.

BnD was formed in 2008 by then director of the University Theater Complex and Office of Initiatives for Culture and the Arts, Dr. Ruben Defeo, with the support of the university's Office of the Chancellor. In 2009, the Main Library's southwing basement was converted into a museum under the supervision of Dr. Gerard Lico of the College of Architecture. Prior to the conversion of the UPD Main Library's southwing basement into BnD, the area had been a reading room and storage for volumes from the Filipiniana section. Lico described the site as 'ideal for adaptive re-use', citing its symbolic potential to rationalize the movement of converting a 'dusty and underutilized basement into a University Heritage Museum' (Pag-Asa ng Bayan 4). Of its inception, Defeo writes that BnD was "an integral part of the plan to convert the campus into a heritage site" (ibid 8). The initiatives led by Dr. Defeo and Dr. Lico were important undertakings that warranted responsibility, organized thought, and a deep sense of care. This had been and remains evident in the lineage of exhibitions and events that seek to present the University of the Philippines' Art Collection "to further inflect the legacy of UP with urgency and imagination" (ibid 1) to its current vision-mission goals in which the museum seeks "to foster interdisciplinarity between academic communities. This will also help forge emergent practices and works that can provide new ways of understanding and responding to current social and cultural issues of national importance".

It is easy to fall comfortable into the high-minded language and overwrought idealization of institution and tradition in forging a brand of pride in/of people and place. Assuring that museum programs are aligned to its original ideas and intentions has always been a constant act of balancing administrative responsibility with intellectual rigor. Underlining the balancing act are bureaucratic maneuverings (UP being a state university meant that its administrative arm was a government office like any other), extremely limited resources, and the lack of tenure to ensure continuity and the presence of dedicated rather than ad hoc ("emergency") administrators and personnel. All this was accompanied by a re-alignment of my own views of UP, taking into account my ideas of it as an outsider, as an undergrad, and as a current employee (albeit contractual). Like most of my peers and predecessors, I also bore the romanticized and lofty view of the university. And before even stepping in as a student, I already took impressions of the university gleaned from popular television and literary references. The university as a place of freedom of expression and experimentation, where the hip hung out, where wunderkinds roamed, and one could possibly walk to every place. The unquestioning affection I had naturally devolved into disillusionment, and was eventually tempered into acknowledgment and a willfulness to make do and do good. This decision to 'make do and do good' is drawn from years of growing with the university and seeing it change as I changed. As an employee, I also commit to the physical and ideal spaces of the university through the kind of exhibition programs the museum has decided to support, organize, and curate. Works and pieces that often harbor timely advocacy: Batang Lumad: Children of the Soil (2016), Fast Fashion: the Dark Sides of Fashion (2016), and the forthcoming Dissident Vicinities (2017), that encompass local and global issues on human rights, the plight of indigenous peoples, the effect of large industries on the well-being of people and the environment.

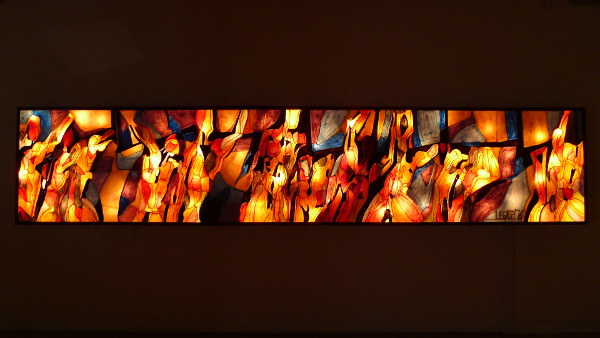

The museum's mandate had been established through its inaugural exhibits, Pag-Asa ng Bayan (Hope of the Nation) in 2009 and Diliman: Tracing the Terrain, Monochromed Memories: UP Landmarks in 2011, as a space where one can recollect and recall (ibid 13). Both exhibitions featured works pertaining to university heritage, albeit prescribing to a purely institutional narrative that cancelled the presence of surrounding communities and how student culture has shaped university identity. In Dr. Patrick Flores' essay Call of the Cellar, he states that "A collection with a long past finds its path towards the future only because it is remembered, made to belong again to a community of other works" and which enables each one to inhabit a common ground and moment (ibid). It invokes the concept of the museum as a heritage space that corresponds to a wider scope of national heritage, expressed through its university art collection, of the museum's very name which "speaks of the possibility of change that animates a forever expectant nation and people" (ibid 14), and its "resonances of the history of the locus" (ibid 15). To further these iterations, more apparent is the museum's potential and ability to promote university heritage beyond its communities, to continuously assess and affirm its position and purpose within the university, and to redefine what the university is, what it has been, and what it can still become. In Call of the Cellar, Flores explains the future of re-purposed spaces, or of any cultural space, through the frame of interdisciplinary practice, as he writes that BnD is "more akin to a creative laboratory, interdisciplinary in orientation, open to the importuning of contemporary art" (ibid). It is also of some interest how Flores described the museum's location at the basement space as the "guts" of the Main Library complex. He adds as a final note: "It is said that such a place is for fools... This is why we are all here. Real work on earth begins "out of this world"" (ibid 17). Passing through this threshold of a statement, we enter this museum underground, feel sound and interact with light. Seen from outside, the BnD is a nondescript and unassuming extension of the Main Library complex. Inside, it has a sense of both astounding loftiness and intimacy. A long stretch of open, cavernous space, its silence was broken by the occasional soundtrack of a film on view at the adjoining Library Media Center or the rolling of mobile shelves. An important depiction of the transition of the space are marked by two exhibitions: A Man and His Relations, which celebrates the life and works of National Artist for Visual Arts Cesar F. Legaspi installed at the BnD Main Hall, and at the Atelyer gallery LangueLounge: forgetory by Jose Tence Ruiz, who had exhibited his installation work Shoal at the Philippine pavilion upon its return to the 2015 Venice Biennale after fifty-one years of absence.

4. Pride and Protest

From its plain white walls and open spaces, the addition of partitions and color lends a sense of direction and focus; the high coffered ceiling amplifies sound and aura which also corresponds with spots of light and dark - a state warranted by an exhibition of works by an artist whose work broke both physical and social boundaries, and who has been endowed with the highest honor. Legaspi was awarded by the national government National Artist for Visual Arts in 1990. A pioneer of the neo-realist genre in painting, he was prominent member of the Thirteen Moderns, and is widely known for his contributions in Philippine Modern Art. His style transformed Western visual grammar into localized textures and scenes, enriching modern design and technique for subsequent generations of Filipino artists. Cesar Legaspi graduated in 1936 from the UP School of Fine Arts, which had been situated at the third floor of the Main Library. This casts an affinity for the space that goes beyond appearances. A Man and His Relations challenges the idea of singular genius in the arts. It rather posits the thought that without love and support from mentors, peers, family, and an entire community, the artist as mentor and master would not come to fruition.

The exhibition consciously and carefully treads the threads of hagiography, noting that "Dealing with the narratives around a National Artist such as Cesar Legaspi makes wading through the overstatements particularly delicate because the rhetoric is expectedly laced with claims to the bragging rights of the nation itself" and yet thorough research also sheds light on the impact of "social mooring and filial enabling" (Legaspi-Ramirez 2017). A Man and His Relations succeeded a previous exhibition at the Cultural Center of the Philippines, Lying in State, which acknowledges how Legaspi's "artistic life became enmeshed in the workings of state propaganda" as he gained popularity during the period of Martial Law in the Philippines (Legaspi-Ramirez 2017) and how he constantly challenged this position in his works. This was further edified even long after Legaspi's death when his family exhumed his remains from the Libingan ng mga Bayani (Heroes' Cemetery) as a sign of protest upon the burial of former dictator Ferdinand Marcos within the same grounds in 2016. The life and works of Legaspi has been largely defined not by works that negotiate and come to terms with social constraints and crises. The Bayanihan mural, one of Legaspi's more visible public art works which had been painted on a sea wall along Roxas Boulevard, emphasizes the importance of working together towards a shared goal. The human figures, in diverse postures, blend with the background and with each other to form a continuous and flowing image. I think this resonates with the concept of identity and acting on a public poetics, in which a crisis is solved through creativity and cooperation, rather than hostility and violence. In making art, there is dignity and progress.

An homage work for Cesar Legaspi’s Bayanihan mural for Kulay ng Anyo Lahi, “Piabe-abeng sikanan” (“Combined Powers”) by 1x with Mark and Alvin Flores, 2017.

Jose Tence Ruiz's LangueLounge: forgetory is a continution of art as an iteration of protest and a document of an artist's life-work. The exhibition is a "commentary on the cult of glib, on the abundance of chatter and often pointless but possibly harmful rhetoric that floods our current media-bombarded existence" (Tence Ruiz 2017). Its installation at the Atelyer of the Bulwagan ng Dangal is a third iteration. Previously installed at the 2017 ArtFair Philippines and at the Far Eastern University, interpretations of the work vary from erotic to esoteric associations.

“LangueLounge: forgetory” by Jose Tence Ruiz. An installation work of (non-functional) electric chairs lined with velvet or assorted used cloths; the styrofoam and fiberglass sculpture of a chocolate brown tongue frames two velvet chairs.

The installation can be primarily taken as a work that explores the transformations and transitions of the meaning of objects based upon its historical context. Its accompanying write-up Easing on Velvet Speech, opens with a comment on the image and symbol of the cross as both referent to salvation and hope, and torment and suffering, and ends in defining 'velvet speech' as "a death sentence announced in lyric poetry" (Dy 2017). Another temporal thread to be considered is the lineage of LangueLounge from Tence Ruiz's Shoal, exhibited at the 2015 Venice Biennale. The biennale serves as a venue for nations to represent history and memory, as well as a brand of cultural and social development through the arts. Shoal is described by Tence Ruiz as a spectre of the "anomalous carcass of an abandoned yet over-utilized US navy vessel that lay unmoving in the Ayungin Shoal of the West Philippine Sea" (Tence Ruiz 2016). Relating the work to the narrative of nation, Tence Ruiz writes: "In the recounting of extended selves, this catatonic offspring of the Second World War chirped its hoary voice, and I listened, like with ear to a conch... ...it spoke of the curdled and encrusted blood of villages and villagers decimated into pulp in service of white skinned salvation" (ibid). It is in this context that the participation of the Philippines in an international biennale is both a point of pride and protest, and an act of acknowledgment and questioning.

5. Towards a Public Poetics

Tying the points stated from ideas of heritage, the history of BnD, and the two exhibitions, I still view BnD as part of a cultural landscape still leaning upon superlatives and singular greatness. As an institution, it espouses inclusiveness, and gives voice to a community to unpack and air out pressing concerns. Whether the museum succeeds in aligning with its vision and mission is still subject to further exploration, and hopefully what can tantamount to a deeper institutional self-critique for BnD and similar spaces. In the same vein, continuously questioning how we identify the value and importance of objects, spaces, and human accomplishments; what can be deemed heritage or when can something be considered one. Whether well-defined boundaries and categories are necessary at all in a cultural landscape whose fields continue to both overlap and fragment, sometimes completely eluding definition and description. It is also worth noting how small, seemingly simple things and back stories can also be valid points in criticism and research, similar to facture in art pieces or what is termed as "the secret life" of spaces; or things and states that are constantly present, even without witness or document, and intuitively felt. Within the two exhibits, one can also see how the state or any hegemonic group counts on culture, both image and (sub)text, as a tool to perpetuate a brand of economic, and political development (Legaspi-Ramirez, op. cit.), and that there are alternative ways to course through these tools to contribute honest and authentic works.

BnD will still undergo changes through cycles in its structure and programs, perhaps will even undergo another complete transformation in the future. Museums and cultural institutions have tried to continuously engage and connected with the different communities surrounding them. This aims to share information and more importantly, provide for cultural groups who otherwise have no access to platforms or resources. This is not to say that our work here is done, there is still room for improvement, especially in the current political and cultural climate of hostility and the refusal to engage on all social aspects. There is still the idea of bringing culture down to the masses rather than listening and considering their own cultural indexes and ways of doing. It is for these reasons, as well as the contexts I have written above, that BnD has inspired interest in spite my spending almost a year on figuring out what to do and how to go about cultural work under a bureaucratic system, which is circuitous and curious at best. Through its location and proximity to an academic community that continues to engage with various publics in addressing social issues, BnD has become a venue for raising awareness. It has been able to work itself towards becoming a safe space for a variety of voices.

Heritage is all-encompassing and inclusive, it is multi-faceted and diverse, and encourages continuing explorations in history and memory, culture and identity. To insist upon heritage as an index of purity and singular narrative is a step away from public poetics and unity.

Works cited

Defeo, Ruben. "Monochromed Memories: UP Landmarks", Diliman: Tracing the Terrain, Monochromed Memories: UP Landmarks, exhibition catalog, 2010, Office of the Chancellor through the Office for Initiatives in Culture and the Arts, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines.

-- Pag-Asa ng Bayan, exhibition catalog, 2009, Office of the Chancellor through the Office for Initiatives in Culture and the Arts, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines.

Dy, May. "Easing on Velvet Speech: Notes on Jose Tence Ruiz's LangueLounge: forgetory", exhibition brochure, 2017, Bulwagan ng Dangal University Heritage Museum, University of the Philippines, Quezon City.

"Fire breaks out at UP Diliman Campus", CNN Philippines, 1 April 2016. Web. 10 May 2017.

Flores, Patrick. "Call of the Cellar", Pag-Asa ng Bayan, exhibition catalog, 2009, Office of the Chancellor through the Office for Initiatives in Culture and the Arts, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines.

Gonzales, Yuji Vincent. "Evaluation of UP buildings, policies sought after Faculty Center fire", The Philippine Daily Inquirer, 1 April 2016. Web. 20 June 2017.

Gonzalez, Narita Manuel. Los Baños, Gerardo T. UP Diliman: Home and Campus, University of the Philippines Press, 2010, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City.

Legaspi-Ramirez, Eileen. "A Note on Jamming and Riffs: Yielding the Solo Spot", A Man and His Relations: The 2nd Exhibition of the Cesar F. Legaspi Centennial Year, exhibition catalog, 2017, Bulwagan ng Dangal University Heritage Museum, University of the Philippines, Quezon City.

Legaspi-Ramirez, Eileen. "Lying in State: The Artist as Citizen Agent", Lying in State: Cesar F. Legaspi Birth Centennial, exhibition catalog, 2017, Cultural Center of the Philippines, Manila City.

Lico, Gerard. "Building Integrity", Pag-Asa ng Bayan, exhibition 0catalog, 2009, Office of the Chancellor through the Office for Initiatives in Culture and the Arts, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines.

Lico, Gerard. "Diliman: Tracing the Terrain", Diliman: Tracing the Terrain, Monochromed Memories: UP Landmarks, exhibition catalog, 2010, Office of the Chancellor through the Office for Initiatives in Culture and the Arts, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, Philippines.

Lico, Gerard. Siglo 20: A Century of Style and Design in the Philippines, National Commission on Culture and the Arts, 2016, Manila, Philippines.

Lucero, Rosario Cruz. "The Music of Pestle on Mortar". Ang Bayan sa Labas ng Maynila (The Nation Beyond Manila), Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2007, Quezon City, Philippines.

Lumbera, Bienvenido. "Sining at Kaalaman/ Kaalaman sa Sining" ("Art and Knowledge/ Knowledge in Art"), a Public Discussion on Art and Education, 27 June 2017, Bulwagan ng Dangal University Heritage Museum, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City. Informal Lecture.

"Milestones in History", The Local Government of Quezon City, 2010. Web. 6 May 2017.

Tan, Michael L., "Update on the Faculty Center Fire", UPDate Diliman, 7 April 2016. Web. 13 June 2017.

Tence Ruiz, Jose. "Emergent Sea: notes on Shoal", Tie a String Around the World: Shoal, exhibition catalog, 2016, Vargas Museum, University of the Philippines, Quezon City.

-- "Re: Proposal to Show LangueLounge at Atelyer". Received by Bulwagan ng Dangal, 10 March 2017.