THE LANGUAGE OF BIRDS: WRITERS LISTEN

by Joshua Lobb

- View Joshua Lobb's Biography

Dr Joshua Lobb is a senior lecturer in Creative Writing at the University of Wollongong and author of the novel-in-stories The Flight of Birds.

THE LANGUAGE OF BIRDS: WRITERS LISTEN

Joshua Lobb with Luke Johnson, Christine Howe, Rachael Lewis-Lockhart, Shady Cosgrove, Adrienne Corradini, Xavier Harvey, Anneliese Hennessy

Introduction

Writers have a complicated relationship with the 'language' of birds. Many writers subscribe to John Berger's understanding of the human-nonhuman confrontation as an "abyss of non-comprehension" (14). In his poem "Poor Matthias," Matthew Arnold articulates the disquiet writers may have when trying to translating birds' lives into human language. He writes: "Still, beneath their feather'd breast, / Stirs a history unexpress'd [. . .] / What they want, we cannot guess" (457). The works presented here show a similar unease with the art of representing birds. In "Mangrove Swamp", Anneliese Hennessy presents her egrets as shadows and echoes, just outside the grasp of language. Similarly, Xavier Harvey shows a flight of 'haunting' cormorants, disappearing from the page as they "stretch into distance". Despite these misgivings, each writer in this collection captures a range of avian experiences: from stories of hatching and survival to elegies for species depletion and extinction.

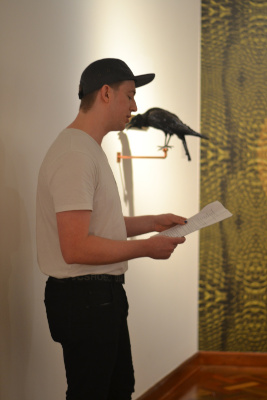

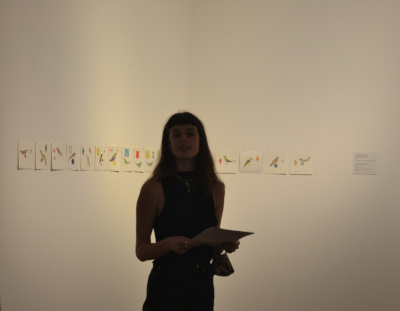

The creative works were first read in situ with the artworks of the Birds and Language exhibition at Wollongong Art Gallery on 13 February, 2022. The original intention was for us to produce writing that responded directly to the artworks; the complexities of COVID-19 lockdowns did not allow for this. Nevertheless, it was extraordinary to discover uncanny connections between text and image. Liam Garstang's Affirmation #4, with its mirrored crow looking back at the viewer, perfectly matches A J Corradini's story of the interaction of a child and a crow discovering ways to "adequately perceive" each other. The playfulness of Laurens Tan's Chicken in a Basket acts as a surprisingly appropriate backdrop for the delicate joy present in Christine Howe's "Retreat". And there are other, less tangible intersections. Fernando do Campo's 365 Daily Bird Lists, with its inventive reconfigurations of bird nomenclature, shows up the sadness of Rachael Lewis-Lockhart's mournful musing over the phrase "population in decline". Ashleigh Eriksmoen's reconfigured items of furniture — which suggest both letters of an unknown alphabet and birds in flight — echo the somersaulting wordplay of Luke Johnson's "Death of Cooley" and the ever-shifting images of pigeons in flight of my own work, "Birds/Words".

The performance ended with a reading of Shady Cosgrove's microfiction "Flight", set in front of Jenny Watson's Young Magpie. Both works are positioned at the moment before something happens: Watson's fledgling looks up, expectantly, waiting to be fed; Cosgrove's birdwatchers wait for swallows' eggs to hatch. Both see this moment of anticipation as a place of fragile hope, "staring up at the blue". I think this is the power of both the exhibition and the writing here: we are, tentatively, opening up possibilities of connection to bridge the species gap.

Retreat

Christine Howe

In April 2020, in the aftermath of the Black Summer bushfires, we welcomed two hens to our backyard. They arrived late one afternoon at our front gate in a cardboard box: a contactless, COVID-safe delivery from Clint, a chook-breeder on Gumtree. We opened the box in the damp twilight, and peered in. The hens peered back. One was a sleek, plump auburn; the other a long-necked, gangly golden-brown. As they acclimatised to our locked-down backyard, the hens spent most of their days scratching, searching for worms and curl grubs — but they also had micro sleeps under the mandarin tree, and dust baths under the lime tree. Whenever we put gumboots on, they followed close behind. They took themselves to bed every night, and came to cluck at the back door in the afternoon. The first time one lay down on her side and spread her wing out like a fan over the warm autumn soil, I thought she was sick or injured. No — she was just resting, stretching out and soaking in the sunlight. Occasionally, the long-necked one flew up onto our kitchen windowsill and balanced there, looking for a handful of oats.

On the morning of the accident, I watched her — this gangly, oat-loving hen — race down the grassy slope from the chicken coop towards our back door. She was vibrant, purposeful, her feathered bottom waddling from side to side as she picked up pace. Our border collie puppy, newly arrived from a sheep farm in Taree, was eating his breakfast by the back step. Too late, I realised she was hurtling towards his bowl. In that still, suspended moment between realisation and response, there was a yelp, a scuffle, a panicked shriek, and by the time I arrived, the puppy was back to crunching biscuits with his sharp little teeth and the hen was huddled on the ground, eyes closed, beak sunk against her chest. I scooped her up, shaking. There was a tiny puncture mark above her right eye, and the lid was swollen shut. She felt weightless, feather-light. I thought she would die.

She didn't. She made a full recovery. While her body was recovering from the shock, she retreated into herself, drawing all her energy inwards. She lay still and quiet in my arms, then in the nesting box, then under a tree, until she could move again, half-blind, running sideways for a week or two until her eye finally healed.

How odd, among all the exhortations to take care of your mental health, guard against burnout, practice mindfulness and build resilience, that I should finally learn the lesson of rest, retreat, regathering and recovery from a chook.

Mirror Boy

A J Corradini

My son had just learnt two new words, both starting with P.

'The crows don't like to be perceived,' he said.

I looked up from the crossword. Three glossy crows were lifting off from the neighbour's clothesline.

'Perceived? Or peered at?'

Samuel shrugged. 'Same thing.'

'Not quite.'

It was true the crows didn't like to be watched. Samuel had been trying to befriend them for months. Walnuts, bread, salami — all had gone to waste. Anytime the crows caught our eyes, they retreated to the eucalypts behind the back fence.

Then one day we pulled into the driveway and saw her at the same time: a crow flailing on the pavement, stuck on her back. Even in her panic, she couldn't right herself. She used the momentum of her frantic flapping to try to scoot away.

We crouched beside her. Samuel frowned. Inexplicably on the edge of tears, I slid my hand underneath her dusty feathers. Upright, the bird collapsed sideways again. No flying, no fleeing.

As I scooped her up, the weight and warmth of her body startled me. Her beak opened and closed, her claws limp.

There was much fussing. We set her up in a basket — gathered twigs, leaves, a scarf. We moved the basket from the table to the spare room to the lounge room floor, beside the glass doors so she could see trees and sky.

I gave Samuel a baby name book and he chose the name Penelope.

We offered walnuts, bread, salami. I shaved off slices of frozen kangaroo and Penelope left them to gather ants. I tried to hold in my anxieties about her condition; Samuel articulated each and every one of his, beginning with 'What if she's bleeding inside and dies sad and alone?'

I got him to hold her in a towel while I felt her body, looking for wounds, finding nothing obvious. Samuel hauled out his animal books and relayed facts about crows which, according to him, are correctly called ravens.

We peered, Penelope peered.

Her eyes were ice blue. She smelt wonderful: earthy, like meat and honey. She filled her box with poop and Samuel mopped it up. Her breath grew rapid if he tried to touch her, but if we kept our hands to ourselves, she appeared stoic and calm. Her movements were minute, tiny rotations of some joint in the neck. She lay on one side, resting on one wing in a way that made me think it was her hip that was injured.

Left alone, we heard her scrambling around to polish her feathers.

In the evening, I stood out on the deck. From the eucalypts, the other ravens made short cawing sounds.

Raven fact: they spend more time looking at you than you do at them.

Inside, Samuel sat cross-legged reading silently beside the basket. He shifted his weight to one side and let out a fart.

'Pardon me,' he said, to Penelope.

Two afternoons later, when the raven still hadn't eaten, I caught Samuel staring into the mirrored glass of the back door, shirtless and oily-haired. Flies, caught inside earlier, were batting themselves against the glass. Samuel held a rolled-up newspaper — the crossword. Perceived, peered. Without breaking his own gaze, he suddenly thwacked the newspaper against the door.

He crouched down and then straightened.

His grin came at me in the mirror, holding the dead blowfly between his thumb and index finger.

Having been adequately perceived, Penelope ate the blowfly.

a poem about a lorikeet

Rachael Lewis-Lockhart

Not at risk, is Google's first response to your species in its search bar. But beneath

in brackets: (population in decline)

Feet stumble outside, air is heavy with moisture and monday morning pace

a pest: a menace, abundant. polluting urban landscapes with excrement and expletives

a pest: a risk, alone. overdoing her deck with silver ladies and lacy ferns entwined with climbing vines of nicotine and lies

ignore the squalls of cars and horns six floors below my lips pull a blueberry vape but it fails to fill this hollow ache

my pest friend maybe you're late. it's been how many days?

a scaly frond shivers, visions of fluoro feathers, alight and tilt your painted face as if to ask 'what's wrong?' but you're not interested in my song any more than I. besides today it's just the neighbour cursing, pushing back creeping vines.

I step inside, hide.

a pest checks the cupboards, they're still bare. it's been how many days?

fumble down stairs, push past glass of the communal roost

enter urban landscape: island of heat, confettied with kebab wrappings and perspiring plastic beneath my feet stick to brick-laid sides, strained on silty sky eyes

register another canopy lost. roots removed and pulverized. in their place a sign glorifying city lives Make way, coming soon: another urban nest

and you, you have been evicted, made to reacclimatise

or maybe not

in brackets: (population in decline).

Mangrove Swamp

Anneliese Hennessy

Golden daybreak. Exposed mangrove roots reveal intertidal

secrets. Brackish water drains, enticing egrets

down from the sea-dew canopy to humid banks and oyster

stilts. White-glare wings widen, feet flare, leaving momentary moulds in mud.

Morning sun froths in the shallows and among aerating roots.

The egrets search. Mangrove crabs flee, basalt

shells demanding light. This is egret hunting ground, between freshwater and salt-

water, in the shallows and on banks that rise and fall with the tides.

In retreating pools: the claustrophobic architecture of mangrove roots.

Arching supports where patrolling egrets

perch. Cartilage shoots secure themselves deep in mud.

Life clogs; cocoons of oysters

and sediment congregations. Sunlight strains, squeezing into oyster

shell crevices where egrets can't follow to lamplit root nurseries of sea-

bass. Safe in the burrowing soft, sediment sways and settles on oil-thick mud

beds. Above, the water line smudges and fades, revised by midday tides,

hesitating. Further inland, egrets

bend skyward, an outstretched leap across mud and roots

to deep sea white-wash skies. Below, in serpentine waterways roots

submerge as the afternoon recedes. Sea bass slip past slicing oyster

shelves. Shadows roll into sunlight and egrets

sink into the canopy. Mangrove leaves, waxy and salt-

brushed by spindrifts, cushion the drowsy flock. Tidal

inundation wavers. Underwater, the silt network has been rewired, and the mud's

topography rewritten — engraving temporary love declarations in mud

on low mangrove branches, engulfing and exposing roots

in unfamiliar ways. The evening invariably re-learns. When the tide-

line lingers fishermen return, harvesting crab, shrimp and oysters.

Mangrove neighbourhoods urbanised — salt-

water agriculture. Brine spiked with bait drifts in sultry air and egrets

rouse. Vaulting from branches in thin light, egrets

settle closer. Surveying needle eyes pinpoint easy entrées before the mud-

raid. Water-wet banks wake. Sunset hunters agitate salt

streams. Mangrove crabs skitter over the crotchet of roots,

scaling trunks and rattling between oyster

clutches to escape sharp beaks. Day falls and the moon pulls the tides

back. Again, mud eclipses, effervescent and sticky on aerating roots.

Life shifts below, and shaking salt from velvet feathers, the sun-bleached egrets

begin a dusk stalk snaking from oyster outcrops to echoing tides.

the cormorant's flight

Xavier Harvey

power poles score the slope, explode onto the flat:

giant eucalypts trimmed of colour, no roots. this haunting

spliced together with ribboning steel, signalling in an empty stretch,

thrumming with abandoned flights. the cormorant

edges its zigzag wings into the wind. along its dark flank, distance

is disrupted. sheared from its algae-blue estuary to strike a chance shore.

in my apartment there are a thousand ferns. they shore

up the corners, burst in feathered sprays across the flat,

nest on window ledges. water and earth in this microscopic distance

is leaden. chairs rust in the mineral heat, traffic stammers to a

haunting stop. outside, I imagine the cormorant

hones its solitary weight into a sharp fletch. fish flicker, shimmer, race from its stretch.

at the base of a wire fence swamped with seaweed, a stretch

of twigs, festooned with crumbling leaves. the broken shore

hovers through piled sticks and a thick tidal stench. the cormorant

egg is a pale blue mirage. the motion of the world falls flat;

only the soft buzz of sandflies and a hint of yellow-green hail haunting

the horizon. smokestacks form white clouds culminating in the distance.

each time I brush the tacky bracken aside, the distance

from my bedroom-to-hallway-to-kitchen in this well navigated stretch

wears a track. in one place, the lino is hollowed out into a fine stream haunting

the way forward and back. I can't remember in what direction the shore,

the bird, the tall sentinel of its high-up perch, its tuk-tuk over the flat.

submerged in crazed foliage, I listen for wing beats of my tangential cormorant

wounded. battering waves hold the sodden cormorant

in a steep, dipping roll. wings flailing, failing. the arcing distance

is a white-tipped funnel of storm-laden saltwater. refuse tangles the flat

web of the cormorant's foot. caught, a flash of white-black-yellow in the stretch

of tidal downpour. it pulls against the rush. on the shore

blink the lights of a cacophony of apartments. the fading rain, haunting.

I place the cormorant breast-down on my lichen-covered couch. its haunting

pattern on the washed-up sea-line litters my retina. the cormorant

is damp and warm under my smoothing hand. small grits of shell shore

in its feathers. I am aware of its nearness and the far-fled distance

of its glassy eyes. laid out, the wildness and wideness of its life I stretch

to comprehend. its full, still frame shrinks the flat.

in the end, this is one cormorant of all cormorants haunting

a place of exile. on the flat of my palm, the bleached egg mirrors the chilled shore.

the cormorants' last grace notes unfurl; stretch into distance.

Death of Cooley (after Garry Shead)

Luke Johnson

In all of Jerusalem

and in all of Judea

and in all of Samaria

laughs the Kookaburra.

Hotblooded progenitor of antipodal delirium,

full-throated, feather-throated father of innumerable miraculous ecstasies,

swallower of worms,

alighter of backyard swing sets,

diviner of lightning storms and other cloudy-scented optimisms,

come down from your eucalyptic throne-top and penetrate me with your mirth,

split me up the middle with your obscene sense of humour

before warbling me to climax with that Christ-sized bill of yours and leaving me pinned

crucified

satisfied

revivified

to the morning's electricity pole.

O, Kookaburra,

Holy Dove of the Illawarra,

what insane fantasies you fill me with,

whipping horses from my flesh like sweat,

sucking paint from my armpits and along my distant cliff faces,

beating snakes from my sandy bushes with your colourful imperialism and strange Irish ancestry.

O, Kookaburra,

descendent of Abraham, Isaac and Jacob,

of David, Heli and Joseph,

what hazy and indulgent prophesies might you convince me of now

in this hour of cerulean immaculacy and deep ekphrastic hallucination?

Kookaburra,

O Kookaburra,

O Kookaburra,

Merry-Merry King of Men Are Thee!

Birds/Words

Joshua Lobb

From the window in the upstairs study, I see pigeons circling the sky. I'm distracted; my attention should be on the words fluttering on the screen. The birds won't stay still. They're lungs, breathing in and out as they turn and weave. They're a virus: expanding and retracting, multiplying. The birds turn again; their wings catch the light and glint like knives.

As a child, I was obsessed with the concept of collective nouns. A pride of peacocks, a clattering of jackdaws, a parliament of owls. My fingers flit over the keyboard. Google tells me that it's a 'loft' of pigeons. The etymology is Old Norse, meaning 'sky; the sphere of the air'. The word shifts through Old High German, where it becomes 'ceiling'; and English, where the word diverges: an attic, a high room; to kick a ball high in the air; and 'lofty': to be erudite, elevated in spirit, haughty and overbearing. I watch the pigeons, now a cluster of glittery-grey smudges. There they are: aloft in the sky, part of the sky, haughtily flaunting their freedom. Here I am: in my loft, but not aloft, caught under the white ceiling, watching the birds spiral higher and higher.

Flight

Shady Cosgrove

There's Covid in the high rise and I'm on the top floor. They wear hazmat suits to deliver groceries and I'm not allowed to leave. Swallows nest under the eaves and fly in anxious arcs. I envy their

mobility.

I set up cameras and live-stream birds to the internet. Something to do — nesting, babies, spring. In the live feed chat: Birdlove71 from Arcata, California, likes the dual perspectives. I write back with too much enthusiasm about the geometry of wing spans. He sends photos of an acorn woodpecker, spotted in his yard — red skullcap, shimmery black-blue feathers.

We watch the swallows for days; sometimes there's a green dot beside his name, we're both online. Mostly, he messages when I'm asleep and I respond in the early mornings, sitting at my window with a cup of strong coffee. It occurs to me the birds could be born at night and so I order an infrared camera — Birdlove's relieved, I can tell — but we don't need it. They arrive in late afternoon.

Birdlove71: It's happening. The hatchlings.

SwallowSolitude: I've never seen this. Not live.

The egg is white with brown spots. A long, thin crack starts at the top and moves down until the shell splits open, claws and beak scrambling. Then, a pink, gelatinous body emerges with a weird, huge head — blind circles for eyes. Everything about the creature yearns upwards. I'm watching the computer-screen. Of course, it's right there, other side of the window, but I can't pull away from the hyper-closeness.

SwallowSolitude: Hypnotic.

Birdlove71: Vulnerable.

There are four babies. Mother and father swoop — disappearing, returning — and the young guzzle food from their beaks. One fledgling seems silly, self-deprecating. Another, bookish. Maybe it's the ruffle of their new feathers.

Birdlove71: Sometimes, watching them, I forget I'm human.

I know this feeling — it comes at night. I slide open the window and perch on its ledge, all feather and delicate bone. With an exhalation, I drop onto currents. The air is cold, glinting with tiny insects. I dip down. In the next block of apartments, I watch a woman through her window; she's wearing a shawl, face cast in television-blue shadows. In the park, a couple walk their dog. Then I climb above rooftops, and follow the freeway with those relentless tail lights.

Birdlove sends photos of fish tacos. I send famous poems I'm not sure I like. He tells me his wife died last year, they're still waiting to hold the memorial. I tell him of my mother's dementia and the cleaner who brings liquorice, the email updates assuring me all staff have been vaccinated. Birdlove works too hard, his son — newly returned to school — keeps losing coats. I admit I'm afraid the world is ending.

Birdlove71: Or beginning.

The next morning, the nest is empty.

Birdlove71: Where are they? Have they fallen?

I'm not thinking. I jolt down the stairwell in my bathrobe. Can't wait for the elevator. I've seen the front of my building on the news — all of the security guards enforcing lockdown — but the foyer is empty, ghostlike, and I rush through the automatic glass doors. The concrete is blank. Thank God. Oh, thank God. I stand in the morning sun, heat on my neck, staring up at the blue.

Works Cited

Berger, John. Why Look at Animals. Penguin. 2009 [1977].

Arnold, Matthew. The Poetical Works of Matthew Arnold. Oxford University Press. 1945 [1882].