Forms for Encounter and Exchange: Field School as Social Form at Laughing Waters Artist Residency

by Marnie Badham, Kate Hill, Ted Purves, Susanne Cockrell, and Amy Spiers

- View Marnie Badham's Biography

Marnie Badham is a social practice artist-researcher in Canada and Australia and Associate Professor at RMIT University.

- View Kate Hill's Biography

Kate Hill is an artist and gardener currently researching clay-soil habitats through a creative practice PhD at Monash University.

- View Ted Purves' Biography

Ted Purves is the chair of the first Social Practice graduate program in the US, at the California College of the Arts in San Francisco.

- View Susanne Cockrell's Biography

With a background in dance and theatre, Susanne Cockrell chairs the Community Art Program at the California College of the Arts.

- View Amy Spiers' Biography

Amy Spiers is a Melbourne-based artist and writer who makes participatory and socially-engaged art.

Forms for Encounter and Exchange: Field School as Social Form at Laughing Waters Artist Residency

Marnie Badham, Kate Hill, Ted Purves, Susanne Cockrell, and Amy Spiers

Listen to the ‘sound walk’ led and recorded by Melbourne-based artist Polly Stanton as you read the essay below.

Introduction

Artist residencies typically offer artists time and space away from the responsibilities of everyday life to create new work. By working in a new context, routines may be challenged with artists finding new inspiration from alternate physical and social environments. Artists can be hosted in local heritage properties, university studios, art galleries or libraries, and now even in public spaces like housing estates or community centres. Publically funded programs can also provide institutional opportunities for audience development, community engagement, public education, or to contribute to forms of cultural exchange and achieve broader national goals (Aitken and Swee 2004) positioned as soft centrepieces for cultural diplomacy. Internationally, there are more than four hundred formal residency programs across 70 countries (ResArtis 2013), which take a number of forms ranging from short-term self-funded individual studio residencies with no requirement for public outcomes, to participation in collective artist retreats, micro-residencies in a person’s home, to multi-partner international institutional programs that employ teams of artists for extended periods.

However, some residencies have come under recent criticism for their lack of flexibility (Zeplin 2009), the circulation of elitism (Bialski 2010), and lack of engagement with local communities. But increasingly, through new forms of socially-engaged art practices, artists are now seeking residencies for experiences of collaboration and community. There are a myriad of conceptual and structural frameworks in which contemporary residencies function around the globe, but with the art world’s burgeoning interest in site-responsive and community-based practices, this article examines ‘the social turn in artist residencies’ through what we might call the collaborative and pedagogic turn (Badham and Hill 2015). To do so, we examine a recent collaborative residency entitled Forms for Encounter and Exchange: a Field School at Laughing Waters Artist Residency.

Field School was one such residency where both artists and hosts were preoccupied with this social form. Over ten days in May 2015, twenty international artists came together to live and work at the historical iconic mud brick houses located in Parks Victoria bushland nearby Eltham, Victoria. Melbourne-based artist researcher, Marnie Badham devised this residency to explore the pedagogic turn found in new forms of socially engaged residency while realising a partnership between the Centre for Cultural Partnerships (CCP) at the University of Melbourne and the Arts and Culture Team at Nillumbik Shire Council (NSC). Together with guest faculty from California College of the Arts, including Ted Purves (Chair of Social Practice) and Susanne Cockrell (Chair of Community Arts), Badham, who is coordinator of the Master of Arts and Community Practice at CCP, sought to expand her approach to teaching outside of the classroom.

Badham, M.: View of theYarra River from Riverbend House. Digital Photograph. 2015

Held at the site of NSC’s Laughing Waters Artist in Residence program at Riverbend and Birrarung houses, as well as a nearby community house Caitlin’s Retreat, Field School was imagined as a collaborative learning exchange between socially-engaged artists and researchers. While reflecting on both the historical and cultural significance of these houses, Field School participants would pay careful attention to the social and environmental contexts of the residency: primarily traditional ownership of the Wurundjeri Tribe and also the recent tragic events of the 2009 Black Saturday bushfires. The peer-developed curriculum was developed from both the NSC hosting partner’s interest in local sites and the participating artists’ proposed responses to place, including a series of practice-based workshops, theoretical lectures, site walks, public art tours, public events, and more flexible open time in situ.

As reflection on Field School, this article examines the social forms of residency through turn of the century social theorist George Simmel’s dual lenses of encounter and exchange. Firstly, this essay offers Badham and Hill’s recent efforts to theorise the ‘social turn in artist residencies’ (2015) drawing on their development of a loose taxonomy of institutional and artist-led residency initiatives as discourse towards the emergence of the ‘guest-host’ paradigm. The article then presents a series of as ‘field notes’ ruminating on place, pedagogy and praxis with aim to examine Field School as social form. These attempts are supported by guest faculty Ted Purves’ preoccupation with Simmel’s concepts of ‘exchange’ and the ‘between-ness’, originally formulated in 1908 (Simmel 1971) and Susanne Cockrell’s frame of story as a social form.

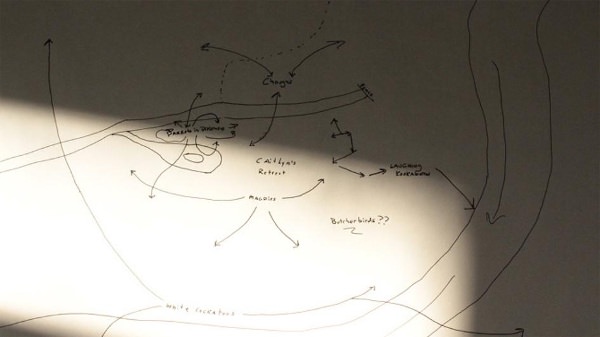

Kotlarczyk, A.: Ted’s Bird Map. Digital photograph. 2015

Rethinking artist residencies: histories, hosts, and guests

Put simply, artist residencies are designed to offer time and space away from their usual working environments. This new environment, whether urban or rural, can inspire practical or conceptual development in artists’ exploration of alternative physical place and social communities. These new surroundings can also provide opportunities for networking (Sienkiewicz Nowacka 2014) and cross-cultural exchange (Asialink 2015). To understand how and why contemporary residencies function, we first draw on the western history of artist retreats and colonies, exploring these forms as early examples of cultural mobility and alternate social economy.

Following these historical roots, residencies have formalised to both raise the profile and working conditions of the artist but also to serve institutional aims by means of social engagement, education and showcasing cultural value through government and academic public programs. These patronage frames of retreat and colony alongside the advent of the institutional residencies offer a distinct dichotomy of the ‘artist as guest’ and ‘residency as host’. Concurrently, independent artist-run initiatives have emerged — also driven by motivations of this social turn. Now taking on the likeness of community arts, cultural diplomacy or sustainability research, residency programs today exist in many forms and have many functions.

Historical Roots of the Artist Residency: retreats and colonies

In Western contexts, the development of contemporary residency forms can be linked back to the Romantic escapism of late 18th century retreats and colonies of Europe and America (Lübbren 2001, Wiseman 2007, Gormley 2010, Hagoort 2010). Under systems of patronage, artists were invited to live on countryside estates, hosted by patron families. They were provided good working conditions including studios and meals, while commissioned to create new works. Similarly, artists would independently escape the perils of urbanity, seeking idyllic rural locations to work together in communal life (Lübbren 2001, Kocache 2012). These early movements saw artists shifting practice by means of travel and working in new locations. These crusades could be critically framed as an early form of cultural mobility, where creatives became transient, crossing borders and engaging in cultural exchange (Mendolicchio 2013).

More than 100 years ago in New Hampshire, the infamous MacDowell Colony began to construct studios one by one, built on the vision of composer Edward MacDowell and his wife Marian. Over time and with heroic fundraising efforts, this American Colony has grown to thirty-two studios scattered across the 450 acres of meadow and forests (Wiseman 2007). The MacDowell Colony invites artists to work in a studio surrounded by the beauty of rural land and while they have separate, private studios, there is a communal nature to the overall property. Artists typically join each other for meals and occasional conversations. Artists live and work together with the main agenda of escaping societal constraints, residing in a natural, utopian setting (Kenins 2013).

This separatist escapism of The MacDowell Colony is exemplified by a number of other artist communities across the globe. Communes today also often focus not only on the social economy of art making but also practice collective values such as environmental sustainability by living close to nature. Like faith-based communities or yoga retreats, these intentional communities are built and designed around a shared vision. The Laughing Waters Artist Residency is located within a cluster of such creative communities, settled by artists on uncultivated picturesque Victorian bushland. The Dunmoochin Foundation houses artists and researchers for years at a time. Near by, Montsalvat is an artist colony dating back to 1934, which still operates today as a private art gallery and site of artist studio. Also in Nillumbik Shire, the Isle of Bends is rural protected land where dozens of artists live near each other on private property with little impact on the protected land.

The Institutional Residency: from pedagogy to cultural diplomacy

Contemporaries sharing the scale of The MacDowell Colony could now include the Banff Centre for the Arts in Canada or SOMA in Mexico. Built on a similar organisational concept to provide positive working environments for artists, these large institutions host hundreds of artists from around the world in a variety of educational, community-based and independent artist residencies. SOMA’s “mission is to provide a forum for dialogue between Mexican and international artists, cultural producers, and the public at large,” and their summer 2015 program “will focus on the idea of excess and its relationship with contemporary art” (SOMA 2015). Banff Centre’s Leighton Colonies provide individual retreats in the unique studios located in the scenic woods. Meals and social activities are taken together, fostering new relationships and collaboration amongst participants.

While the forms of retreats and colonies remain today, the functions of residencies have shifted over time by means of both policy and artistic drivers. Not dissimilar to the divisions seen across gallery systems in either public or independent exhibition space, motivations may be different. Two clear categories of residencies have been distinguished – institutional/public and artist-initiated/independent. What we call here an ‘institutional residency’ is hosted by a government organisation or agency. They often take place in public establishments interested in public cultural value such as libraries and museums, but schools, hospitals and prisons now increasingly host artist programs. These forms of residency may also place artists directly in community contexts, to further aims of engagement, education, or regional development. Not unlike early patronage systems, the category of institutional residency would typically support artists financially towards a shared outcome.

The local government association, Nillumbik Shire Council, facilitates the Laughing Waters Artist Residency program, the site of Field School. Supporting artists in residence at these iconic properties is one strategy to value the cultural heritage of the residency buildings (NSC 2015). This program supports the creative production and need for retreat by visiting and local artists, but also draws attention to the significance of the mud brick houses built by local architect and artist Alistair Knox and Gordon Ford. Laughing Waters provides studio and housing and can also offer engagement opportunities for public viewings and artist talks, should the artist be interested.

Temporary relocation into new cultural settings is often inspiring to artists (Residency Programmes Forum 2014) and can promote international networks between institutions and arts organisations (Australia Council for the Arts n.d.). The travelling artist has almost become a new breed in contemporary art today. Field School artists David Brazier and Kelda Free’s itinerant practice sees them working site-specifically, negotiating the complex relationships that constitute ‘site’.

They examine relationships between a location’s social, economic, political and institutional dimensions and their personal histories, working methodologies and artistic autonomy. They seek tensions within these relationships and employ a variety of social forms and gestures in order to interrogate and re-imagine the systems and spaces they occupy. (Delfina Foundation 2014.)

However, international residency programs have been critiqued for promoting carbon-heavy travel and short term visits to places seeking community engagement, while ignoring broader environmental and social concerns. Kenins argues that ‘sometimes, in far-flung areas, there is an awkwardly colonial relationship by which residencies court foreign artists under the guise of enlightening the locals’ (2013) and Pryor critiques residencies, comparing residency artists to ‘fly-in-fly-out-workers’ in the Australian mining industry who benefit from their time in remote contexts while reciprocating very little relevance or value (2012). Kenins argues that these concerns can be addressed in local artistic practice and engagement (2013), which appears to be the case with Brazier and Free.

Residencies facilitated by larger institutions with international partnerships not only provide time and space, but foster valuable new relationships between global and local contexts. Another of Field School’s artist participants, Canadian First Nations artist Jason Baerg, has also participated in a series of international residencies, in particular the Indigenous Arts Residency Exchange. He recently returned to Australia twice to use specialised equipment at the residency and connect with other Indigenous artists’ practices unique to this context. This program, facilitated by the University of Lethbridge in Canada in partnership with RMIT in Melbourne, ‘aims to connect and expand Indigenous culture and explore ideas of Indigeneity to develop and strengthen dialogue and knowledge exchange between Canada and Australia’ (Badham and Hill 2015). For internationally mobile artists like Baerg, Brazier and Free, residencies like these assist in the development of real collaborations with other artists, resulting in a series of new works, exhibitions, or teaching opportunities. But the transient and temporary nature of their engagement is not simply a condition of a residency; this meaningful relationship to context or community also becomes the content of their work.

Artist-initiated Residencies: curatorial interests and the social turn

New forms of artist-initiated residency projects are typically curated or collaboratively devised to explore a particularly salient idea. Socially-engaged residencies often bring artists together who share an interest in a conceptual or geographical site. In recent years, there have been an abundance of residencies that examine sustainability and mobility in the context of climate change and global conflict (Artist as Family 2015, DAAR 2015). Like the provocations on ‘site’ of Brazier and Free, these residencies consider the relationship between the local and the global. Perhaps as a critique of the art world itself, these residencies are situated far outside the institution, often off the grid in grassroots contexts. They may take place in alternative locations such as old school houses in post-industrial towns (BCSC 2015) or as a shared journey on boats, trains or walking trails (TSAC 2011, Signal Fire 2015, Access Gallery n.d.).

Badham, M.: Jen Rae’s Biomimicry Workshop, Digital Photo, 2015.

Developed more like an artist's project than a public program, curatorial frameworks found in artist-initiated residencies appear to be more flexible, shifting with the cultural climate and the interests of contemporary artists. Autonomy from institutional and policy frames allows these residencies to develop specialised programs based on local contexts or curatorial themes. These kinds of residencies are usually less financially stable and require contribution from the artist.

These kinds of experimental social art residencies are growing in popularity as the possibility for short term projects in diverse locations becomes more interesting for the itinerant artist, via funding for specific, one-off projects, suited to particular disciplinary artists and communities, and cheaper for regional or international travel. Social arts practice and subsequent residencies tend to critique the ‘ivory tower’ and the central focus is taken off the notion of the prodigious artist, onto the importance of examining a particular located problem. As questions or provocations, residency themes may engage artists in greater contemporary political and social concerns. This becomes inherently social, as individuals come together from different geographical and practical contexts to think, make and share as an exchange. Nato Thompson argues that ‘isolated artists must focus on speaking, while groups of people coming together must focus on listening – the art of not speaking but hearing’ (Thompson 2012).

While this short article cannot rehearse Badham and Hill’s full research to include other forms of residency more closely linked to community-based arts practices and inter-sectoral partnerships across health, justice or housing, it has so far offered a number of theoretical frameworks we can now apply to Field School. Extending concepts of retreat and colony, these examples have provided a loose taxonomy of both institutional and artist-initiated residency models, beginning to frame the ‘collaborative’ and ‘pedagogic turns’. Together with social exchange such as collaboration, community engagement or simply shared meals, artists hosted in a residency context are offered time and space away from everyday life. These interactive spaces have become sites of the social turn – as forms for encounter and exchange.

Field School at Laughing Waters Artist Residency put forth a proposition of residency as a social form for encounter and exchange. Understood here as a hybrid example across the abovementioned loose taxonomy, the rural retreat focused on peer learning and social form. Field School took place an hour outside of the city, away from our everyday lives in bushlands along the Yarra River. As institutional hosts, NSC and CCP first developed the curatorial framework of social form – inviting artist applicants to respond to this proposal. Like a colony in the short term, Field School aimed to be non-hierarchical by co-designing the multilayered curriculum and positioning faculty and students to work and live together – sharing meals, chores, and recreation. Together, Field School took on the conditions of an artist-initiated project to explore the residency site of social exchange amongst artists in the context of the broader community layers of traditional owners, hosts and artistic communities of Eltham.

Field School: framed by place, pedagogy and praxis

Forms for Encounter and Exchange: A Field School at Laughing Waters Artist Residency was designed as a collaborative learning environment for socially-engaged artists. Devised by Badham as a way to extend pedagogic models, Purves and Cockrell from California College of the Arts were invited to the faculty team. This team was extended by the local knowledge of Margaret Summerton (community cultural development worker, NSC) and contributions of Kate Hill and Amy Spiers (both independent artists and researchers at CCP). A call for ‘Expressions of Interest’ was circulated through educational and artistic networks. This proposal targeted artists who had interest in the site and the particular sociality of Field School, rather than the merit of their artistic history. As such, applicants were not asked to send extensive CVs nor support material, but to write a short proposal answering three questions, which encompassed the philosophical dimensions of the residency:

- ‘What is your motivation for applying to this collaborative residency and what is your interest in the site of Laughing Waters?’

- ‘Please describe your art form/community practice.’

- ‘What is your proposed contribution to the peer learning environment?’

This curatorial process placed emphasis on the residency site and history, as well as the practice intention of peer learning and social exchange. The call for an interest in the forms of encounter and exchange rather than medium specificity resulted in a remarkable group of individuals including a landscape sound and video artist, a Buddhist installation artist, a ceramicist who has worked on the site previously, a storyteller, a photographer, and artists concerned with environmental and social sustainability.

Field Notes on Place: local history, culture, and communities

The residency officially began through a ‘Welcome to Country’ ceremony hosted by the Traditional Owners of the land, members of the Wurundjeri Tribe. Through a smoking ceremony and storytelling performed by Aunty Judy and Uncle Bill, Field School participants were introduced to the site. We were educated about pre-colonial and contemporary histories of place as we sat together in the sun at Birrarung House with other local community and members of Nillumbik Shire Council.

Kotlarczyk, A.: Welcome to Country Ceremony. Digital photograph. 2015

Together as large group, we ambled down to the river to see where the pre-colonial eel traps were still located, with growing awareness and connection to place through cultural and environmental teachings. Later that evening in front of the fireplace, located high above the sound of flowing water at the Riverbend House, author and local historian Jane Woollard joined us reading stories about Laughing Waters Road, providing us with an evocative and informative account of the neighbourhood, locating us in its complex layers of spaces and stories.

Field School participant Abbra Kotlarczyk’s interest in the history of the site originated from her relationship to the late photographer Sue Ford, who with her children lived in the mudbrick house behind Birrarung. It was during this time that Ford produced a significant series of photographs considering feminist political discourse through works placing female figures in the landscape. Kotlarczyk initially stated that her ‘… interest in developing some of the cross-generational parallels between Sue’s coming-of-age and (her) own can be pinned to key themes such as environmentalism and the mediated landscape, alternative histories and feminist identity’ (Kotlarczyk, 2015). Kotlarczyk performed a reading of a personal letter to the photographer, standing before the ruins of Ford’s mud brick house. Linked to Ford’s archive and her own photography practice, Kotlarczyk also took on a role of social documentation as another type of field notes, creating an online platform for dissemination of activities, theory and reflections that can be found here.

Stanton, P.: Ford’s House Entrance. Digital photograph. 2015

The site of Laughing Waters Artist Residency is Eltham, home to several prominent artist colonies. In a field trip around the area, participants were taken on a tour of historical Montsalvat, a working artist colony and another residency site. Field School participants were also taken to several public art sites that were constructed following the 2009 bushfires that severely affected the community. The first site we visited was a mosaic bench seat at St Andrews market, hand made by members of the community, facilitated by local artist Chris Reade. The tiny segments of broken pottery collectively told a story of fire and regeneration. Following this, we visited ‘The Blacksmiths Tree’ in Strathewen. This tree, hand forged and containing contributions from blacksmiths all over the world, stands as a memorial to “all those who perished in the Black Saturday Fires, for those who fought the fires and for those who continue to live their lives with hope and courage (Australian Blacksmith’s Association n.d.) By visiting these nearby sites and talking with local artists, we began to understand some of the historical layers sitting beneath our temporary experience as attachment to place in Eltham.

Another day trip took Field School participants to the nearby Eltham Community Library Gallery for an art exhibition by faculty member Kate Hill and her collaborator Craig Burgess. After undertaking a solo artist residency at Laughing Waters Artist Residency in 2013 at Birrarung, Hill began digging clay at a neighbour’s house nearby on Laughing Waters road. The exhibition, Digging, presented an installation of videos, process-based works, and final fired ceramic pieces, taken from the excavation site over a two year period. In this work, Hill and Burgess considered their temporal engagement with materials and place, unearthing geological time, production, and ceramic processes. In the form of an artist’s talk, the duo detailed their two-year process, connection to Eltham, and desire to show the work locally in the mud brick library gallery – also constructed from the same local red clay.

Hill, K.: Local clay. Film photograph. 2015

The value of arts in the Eltham area remains strong, built on decades of artist activity in studios, colonies and communities across this green wedge of uncultivated land. The mud brick residency houses feature in this history amongst reputable commitment to public art and community cultural development practices. The Nillumbik Shire 2011-2017 Cultural Plan presents a mission ‘to enable opportunities for local communities to participate in creative activity and express their cultural identity through the arts, support the creative economy, and preserve and make manifest our cultural heritage and local history’ (NSC 2007). The public art projects that took place following a series of devastating bushfires that effected several communities across the Nillumbik Shire, highlights this importance of arts for community and health benefits. We heard first hand from community members and artists on the importance that the process of making the artistic works, healing wounds and nurturing relationships.

Field Notes on Pedagogy: social theory, story and ethnography

Field School helps to illustrate not only the social turn but also the recent ‘pedagogic turn’ in residencies. Like Banff Centre, SOMA Mexico, and perhaps more closely the RMIT Lethbridge Indigenous Artist Exchange, art schools and universities regularly host reputable artists as guest faculty so their students may benefit from external specialist critique or expert master classes (Badham and Hill 2015). To this end, Purves and Cockrell joined Badham as guest faculty to develop a theoretical framework for Field School to contain the participants’ contributions including creative workshops, social events and artist talks. Ted Purves and Susanne Cockrell each provided what we might consider framing ‘keynote papers’ on art, community and social form.

Firstly, Purves’ lecture examined concepts of exchange and encounter through his preoccupation with the writings of Georg Simmel, which explore the notion of interaction and the interplay of subjectivity and objectivity. Purves’ lecture at the start of Field School located our work in the field socially-engaged art and theories of social form.

Badham, M.: Ted Purves Talks Simmel, digital photograph, 2015

Purves explained how Simmel believed that while there were endless social forms evolving and falling into disuse across the breadth of society, these forms fell into two larger categories. The first, which we discuss next, he saw as tied to praxis. They are the forms through which we address our needs through interaction with others, and can be more linked to economic systems. He identified the second category as ‘play forms’ of the social. These forms, which include such things as games or coquetry, do not serve a real need, and exist because there are times in our lives when we wish to ‘play’ at the social. Following Simmel (1971), Purves argued ‘Devoid of pragmatic content, they exist for those moments where we wish to participate in the “world” of society as an end in itself”. This, then, is one further lens through which to consider the artists and a space such as Field School as occupation of social forms. A physical performance workshop, where participants interact through a non-competitive ball game, doubles as another social form altogether, “playing” at the idea of loss and gain. This game can produce something of value, and we would suggest that this value could be thought of as an encounter.

‘Encounter’, in this case, is that moment when we are confronted with an Other. However this Other is not simply a thing that is separate from ourselves, it is an encounter with someone that makes us realize our own individuality by experiencing them as an active, and largely unknown entity, an undiscovered country. At Field School, Other began as each other, then shifted to the local community and perhaps finally ourselves as we realized our separateness the local. Considering ‘encounter’ as the primary product of social art practices shifts its primary goal away from some of the more teleological purposes that have been required of public art throughout its history. While these earlier results-oriented goals, which include national commemoration or community representation (ranging from public sculpture such as the metal workers' tree to neighbourhood mosaic tile artworks) as well as the instigation of social action, have not necessarily receded; they have become increasingly complicated within our globalised, multi-cultural society. Field School became in itself this place of encounter, as social form in itself, without designating particular outcomes for the exchange.

In Susanne Cockrell’s presentation, ‘Story and Storytelling as a way to Reveal and Bend the World,’ she introduced Welsh storyteller Martin Shaw’s idea of the Story Carry-er. He says that not everyone need be a storyteller, those who speak myths and stories orally into communities, but everyone is a story carrier. She explained we all have an embodied way of communicating. Story carrying is less about the teller than spaces between that are interpenetrating and aggregate. She asked, ‘What stories are we carrying? What story do we want to tell?’

Cockrell explained, story or narrative becomes a way to carry things and takes things with us. As practitioners working in social, public and communal spaces, we extend and distribute parts of ourselves through the work we make. This involves listening, touching and being touched, activating and generating actual and symbolic gestures. As artists we often want to stretch the capacity of what a story or the world can be. In works that unfold in time and involve people, communities and place, we often find ourselves inside stories, conversations, interviews, social issues, and public encounters that are not our own.

Cockrell’s presentation laid a foundation for a subsequent workshop by Gretchen Coombs. As guest faculty, Coombs facilitated a writing session on creative ethnographies as a research or critical reflection method, to position oneself in the ethics of representation. Laughing Waters Field School provided a fertile ground to investigate the presence of multiple voices and ‘contents’ (Simmel 1971) when telling stories. Other lectures included Danny Butt’s ‘Colonial Hospitality: Learning to Host, Learning to Visit’ and Amy Spiers’ ‘Rejected Gifts and Failed Exchanges’ which each served as critical space for Field School participants to continue to reflect on practice.

The first and final in the series of Field School workshops explored a framework of human ecology as a way for participants to critically reflect and make sense of our experiences. Facilitated by Asha Bee Abraham, this conversation was strategically placed to bookend the ten-day period. Abraham surfaced the interrelation of her three main layers for analysis: the self, the soil and the social. This trifold frame could contain reflection on our individual experiences and practice, the external physical environment of the site, and the broader community. Field school participants presented these reflections later through a live performative workshop once back in the city the next week to an art school audience.

Field Notes on Praxis: embodied encounter and exchange

The more formal pedagogic content offered by the lectures and workshops by Purves, Cockrell, Coombs, Butt, Spiers and Abraham were intertwined with other ways of knowing. Artistic knowledge and the collaborative meaning-making of exchange was realised through a series of creative workshops and social forms.

Following Woollard’s storytelling at Riverbend the first night, local Maori artist Julie Tipene O’Toole welcomed us into a relational artwork of welcome and engagement titled Over the Teacups. For this participatory project involving social exchange and ritual, we were invited to select a teacup from a varied collection placed on a table, each teacup containing an accompanying story. These stories followed from the previous life of the project, which Julie described, and participants responded with their own story about their choice of teacup. For instance, Badham chose a lovely flowered piece as it reminded her of her maternal grandmother’s house. This engaged workshop was a way to have participants get to know each other a bit more personally, and shifted the reader-audience dynamic of Woollard’s reading to a participant-led and collaborative exchange. These types of exchange continued over the preparation of meals and eating together as well as during leisure time.

Tipene O’Toole, J.: Over the Teacups, Digital photograph. 2015

The program unfolded each day before breakfast around a regular group meditation session hosted by participating artist Hartmut Veit. Here in the glass-walled sunroom studio, artists sat in silence, sharing a space free of verbal or visual dialogue to centre one’s self for the day. Meditation also extended into a silent group walk. Creative workshops following artist talks such as the photographic anthotype with Canadian artist Sarah Fuller, and a Biomimicry exercise with Jen Rae, enabled the participants to collectively explore a material response to the site and residency context. Fuller asked the participants to gather materials from the grassy field, allowing a slower, deeper exploration of our nearby environment. The process of walking to find materials added to the larger process of conceptual and physical mapping taking place over the ten days.

Jen Rae’s interactive workshop was based on the concept of Biomimicry, or the ‘conscious emulation of nature’s genius’. Through a series of group activities, participants explored how ‘ideas of ecological stewardship can be conveyed through (a) form of interactivity and movement with others’ (Rae 2015). Shifting us from environment to self, Tania Canas’ Dojang workshop referenced ‘the holistic practice of taekwondo, as a lead-in to Brian Fay’s (2002) writings of self, other and narrative (to) discuss spaces as forms of encounter and exchange, as well as the self in space’ (Canas 2015). Her theoretical framework was concerned with questions including: ‘Do we have to be one to know one?’ and ‘Do we need others to be ourselves?’ which have resonance with Simmel’s position on shared experience, and what we give or gain in exchange: ‘Most actions which at first glance appear to consist of mere unilateral process in fact involve reciprocal effects’ (Simmel 1971). Canas’ workshop shifted these conceptual questions into a physical awareness, through a series of actions negotiated in a shared space. This approach to praxis allowed for an embodiment of Abraham’s overarching themes of the self, the soil, and the social for the Field School residency.

Kotlarczyk, A.: Canas’ Dojang Workshop. Digital Photograph. 2015

Pursuing similar frames of bodily response to space, performance artist Adva Weinstein initiated a physical performance workshop that invited participants to consider their centeredness, and orientation in the space of the residency site, through an exercise in the field of ‘widening of the performative gaze’. This enabled participants to feel the space between themselves, others and objects, tying again to Abraham’s notion of the ‘self, soil, and social’, and Martin Buber’s ideas around the non-differentiation between humans and objects (Friedman 2002).

Whilst the majority of participant contributions to the peer environment were participatory, there were also a series of artist talks delivered in front of the fire at Caitlin’s Retreat. These sessions included most visual artists: Jason Baerg, Margaret Summerton, Polly Stanton, Abbra Kotlarczyk, Sarah Fuller, Jen Rae, Dave Brazier and Kelda Free, and Adam Douglass. The artists showed slides of their practice history or used it as a platform to discuss individual projects, welcoming a critique to follow. This allowed for an understanding of the various practice histories underpinning participants, and explaining what may have influenced them to arrive at Field School. Some of these artists presented their visual work again at the public Pecha Kucha with other local artists and audience at the Eltham Community Theatre venue.

Badham, M.: Artist Talks by the Fire at Caitlin’s Retreat, Digital Photograph, 2015

Polly Stanton, who makes immersive video, sound and photography works from quiet, desolate and epic landscapes, stepped out of her role of documenting Field School, to discuss her practice to date, including a work presented for the Bogong Village artist residency, Bogong Centre for Sound Culture. The synopsis of this work enabled an understanding of her conceptual, environmental and aesthetic interests. The labour and dedication to the work (Stanton climbed a mountain to gain footage), layered with a sensitivity and quietness, painted a picture of both her practice and her personality. The artist talks presented an opportunity for Margaret Summerton to step out of her faculty role as the Nillumbik Shire Council Cultural Development Officer, to discuss her socially-engaged art practice. Summerton reflected on Field School as a challenge for her as she felt she was straddling various staff, participant, artist roles, and welcomed the opportunity to discuss local community art projects contextually connected to the residency site. Extending Purves’ provocations exchange and encounter, the artist talks of Douglass, Rae, Spiers, and Baerg each reflected on their work as social form directly.

Concluding Field Notes: towards artist residency as social form

This article aimed to examine artist residency as social form through the recollection of our experiences at Forms for Encounter and Exchange: a Field School at Laughing Waters Artist Residency. However, what we have presented is not conclusive theoretical contribution, but rather an interrelated series of descriptive ‘field notes’ examining encounter and exchange. As artists and researchers engaged in socially-engaged arts practice and pedagogy, our interests lie in the experimental and the experiential in which we continue to open up new questions in practice, rather than offer answers.

Marnie Badham and Kate Hill offered the last presentation, a co-delivered discussion entitled Rethinking Artist Residencies. This was an informal ‘work in progress’ conversation outlining the motives of our new research exploring the social turn in residencies. First laying out the start to a new taxonomy of artist-initiated and institutional forms, what resulted was both a generative and generous conversation exploring the residency as social form, examining our pedagogic and collaborative intentions. Questions about the ‘pedagogic turn’ and ‘what in fact are the elements of a residency’ were asked. Do artists need to be provided lodging for it to be a residency? Does a residency need to take you to a new place? Are residencies a new form of cultural tourism? Have collaborative artist residencies become a new experimental social art form? The conversation ensued to revisit the traditional artist-guest and institution-host relationship dichotomy with acknowledgement of new social forms of collaborative artist-initiated residency expressing interest in attachment to community and responsiveness to place.

Badham, M.: Open Day Performative Sunset Walk. Digital photograph. 2015

Together at Field School, as a somewhat foreign place Simmel would call of ‘betweenness’ – as a social and collaborative space, our understanding of our own practices was deepened through engagement in Abraham’s trifold framework of self, soil and the social. We stimulated this reflection with a series of modes of reflexivity including storytelling, art making, talking, playing, meditating, walking, listening, visiting the local market and sharing meals at the pub. Purves’ preoccupation with Simmel, and Cockrell’s reflections on story as medium at once became our own. As an arena to examine social form, Field School became what Simmel suggests is the ‘sum of parts greater than that exchanged’ in the creation of meaning and relationships. The positioning of Field School as a collaborative residency, which included group field trips and meaningful interactions with locals facilitated a more dialogical transaction around art, where storyteller and listener offered their ‘contents’ and operated in the ‘betweenness’ of what could in other instances be a independent experience.

References

Access Gallery. (n.d.). "Access Gallery 23 Days at Sea." Retrieved October 28th, 2015, from Web.

Aitken, P. and Swee, L., eds. (2004). 35,000 days in Asia: the Asialink Arts Residency Program. Melbourne: Asialink Centre, University of Melbourne.

Artist as Family. (2015). "Artist as Family." Retrieved October 15th, 2015, from Web.

Asialink. (2015). "2016 Asialink Arts Residency Program Application Information - Asialink." Retrieved 1st October, 2015, from Web.

Australia Council for the Arts. (n.d.). "International Residencies | Australia Council." Retrieved 25th September, 2015, from Web.

Australian Blacksmith’s Association. (n.d.). "The Tree Project". Retrieved Feb 14, 2016, from Web.

Badham, M. and Hill, K. (2015). "NEW TIME: rethinking the 'social turn' in artist residencies." Parse Journal.

BCSC. (2015). "Bogong Centre for Sound Culture." Retrieved October 2nd, 2015, from Web.

Bialski, P. (2010). Transient spaces: the tourist syndrome. Eds. Sorbello, M., Weitzel, A. Berlin: Argobooks.

Canas, T. (2015). "Expression of Interest to Fieldschool". Unpublished document.

DAAR. (2015). "Residency | DAAR." Retrieved October 15th, 2015, from Web.

Delfina Foundation. (2014). "David Brazier and Kelda Free". Retrieved Feb 14, 2016, from Web.

Fay, B. (2002). "Unconventional history". History and Theory, 41(4), 1-6.

Friedman, M. S. (2002). Martin Buber: The life of dialogue. New York: Routledge.

Gormley, M. (2010). The life and practices of the artists' Colony, Aspire Media LLC: 35.

Hagoort, E. e. (2010). The ON-AiR Workshops Manual. Netherlands, Trans Artists: 15.

Kenins, L. (2013). Escapists and jet-setters: residencies and sustainability, C The Visual Arts Foundation: 8.

Kocache, M. (2012). "Setting the Record Straight: Towards a More Nuanced Conversation on Residencies and Capital." Art East: the global platform for Middle Eastern Arts, Winter 2012 Artezine, Retrieved Feb 14, 2016, from Web.

Kotlarczyk, A. (2015). "Expression of Interest to Fieldschool". Unpublished document.

Lübbren, N. (2001). Rural artists' colonies in Europe, 1870-1910 / Nina Lübbren. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

Mendolicchio, H. B. (2013). "Art and Mobility: An Introduction." Interartive 55.

NSC. (2015). "Programs." Retrieved October 28th, 2015, from Web.

Pryor, G. (2012). "Polemic: Socially engaged FIFO art?" Artlink 32(1): 14-16.

Rae, J. (2015). "Expression of Interest to Fieldschool". Unpublished document.

ResArtis. (2015). "Microresidence Network." Retrieved February 14, 2016, from Web.

Residency Programmes Forum. (2014). "Conclusions and Recommendations | Residency Programmes Forum." Retrieved 5 January, 2014, from Web (PDF).

Sienkiewicz Nowacka, I. (2014). "How to start and sustain an artist residency field?" Residency Programmes Forum Pogon Zagreb. Web (Youtube). 2015: Video file.

Signal Fire. (2015). "RESIDENCY - SIGNAL FIRE." Retrieved October 1st, 2015, from Web.

Simmel, G. (1971). Exchange. On Individuality and Social Forms. Chicago, The University of Chicago Press: 43-67.

SOMA. (2015). "Soma Mexico - About." Retrieved October 28th, 2015, from Web.

Thompson, N. (2012). Living as form : Socially engaged art from 1991-2011, New York : Creative Time Books, 2012.

TSAC. (2011). "Trans-siberian Arts Centre." Retrieved October 28th, 2015, from Web.

Wiseman, C. (2007). A Place for the Arts: The MacDowell Colony, 1907-2007. New Hampshire, MacDowell.

Zeplin, P. (2009). “Trojan Tactics in the Art Academy: rethinking the artist in residency programme”. Scope: Contemporary Research Topics (Art and Design). 4, 66-77. Print.