The Divine Trash Strata

by NANCY MAURO FLUDE

- View Nancy Mauro-Flude's Biography

Nancy Mauro-Flude is a Tasmanian artist and theorist, and Assistant Professor in the Department of Communications and New Media at National University of Singapore.

The Divine Trash Strata

Nancy Mauro Flude

00 Notes from the diary

…the clue lies there...symbols of the divine show up in our world initially at the trash stratum. - Philip K. Dick (Davis 2006)

I am in Haiti, standing in the Grand Rue, a slum in Port-au-Prince, watching a plastic crocodile transmute from an innocent child's toy into a horrifying agent of revenge as it devours a woman feet first in one gulp (figure 1). Glimpsing these mutating entities, I am reassured to know, I am where I need to be. This is an omen. I have treasured for many years a similar doppelgänger. A crocodile with a woman hanging out its mouth (figure 2). It exists in the trash stratum, formerly, having being ‘ripped from a magazine’ its subsistence in my personal archives anticipates ‘a one day to be framed’ possibility.

Figure 1: Children’s Artwork at Atis Resistanz, Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

Figure 2: A scene from Pina Bausch’s The Legend of Virginity Wuppertal Theatre Germany. Photo: Helmut Newton

Apart from this small mythical creature, I am surrounded by a maze of dirt-encrusted skulls dug from cemeteries and welded onto poles (figures 3-5). This place resonates with life, but is clearly rooted in death. At the entrance I have already been greeted by gatekeeper Papa Guédé, a trickster, warrior and messenger of destiny crafted as a Vodou sculpture constructed from the skeleton of an old car, a bed-frame, miscellaneous scrap metal, rusted iron loops and a formidable wooden phallus suspended on a spring, which I was told, if you plunk, it brings good luck (figure 4).

Figure 3: Papa Guédé at the first entrance of Atis Resistanz, Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

Figure 4: Children of Atis Resistanz with a Papa Guédé Sculpture just beyond the entrance of the Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

01 Atis Resistanz

During November-December 2009, I attended the first Ghetto Biennale hosted by a community of artists who live in the Grand Rue and refer to themselves as Atis Resistanz. Combining Vodou and sculpture, their artwork is made from trash and paraphernalia. Vodou is the traditional spelling of the religion and culture of the Haitian people which arose from the fusion of different traditions, including the Hermetic-Cabalist customs of the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. For the purposes of this text I refer to general vodou Culture and specifically how its practices have existed in subterfuge over long periods of time and become manifest in domestic habits, appurtenances and paraphernalia. Atis Resistanz repurpose discarded devices, clothing and objects, from the so called ‘first world’. In the guise of benevolence, the paraphernalia from people from very different situations is transported to Port-au-Prince. It does not come as a surprise that most of the castoffs and consumer items are redundant. Ankles are likely to flip on unstable footpaths when wearing high heels once worn on the smooth asphalt streets of Toronto. These makers seemed to me the final repository of the marvelous, the last possessors of the wand of the magical goddess Circe.

Motivated by the rejection of their visa applications to attend the opening the Miami Art Fair featuring their own artworks, Atis Rezistanz concocted the Ghetto Biennale. A call to arms for an international art party came via an email chain (Gordon). The people whom responded consisted of academics and artists from America, Jamaica, Canada and a cluster of Londoners mainly from the KLF crew. It was significant that Bill Drummond, former member of the KLF, was at the event as his ‘money-burning’ gesture, titled The K Foundation Burn a Million Quid (1994) was a momentous act for Eugene, an Atis Rezistanz elder. One could argue that the money burning act, which aimed for a response in the contemporary art arena, found almost no resonance, except within the London acid-house pop tabloid culture from which it came, and had filtered its way to Haiti, where much of the trash from the first world floats.

Figure 5: Atis Resistanz, Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

I fall asleep and awaken to the beat of a drum resonating through the aether. From somewhere far off in the distance there are remote signals I can not decipher. Vodou permeates everything. Although there are religious ceremonies, vodou is first and foremost a social and cultural system, inseparable from the everyday life of most Haitian people. The people joke that the current population is 90 per cent Catholic, but 100 per cent Vodou.

In the daytime I dodge the broken concrete, the history of a nation that led the first successful slave rebellion engulfs me as I walk across bridges, climb up and down hills through the frenetic streets. At night, I drink rum like any honest pirate girl should.

The Haitian revolution in 1804 resulted in the permanent abolition of slavery on the island with a declaration of independence. These matters have overwhelming meaning for many of the Haitian people, an island once controlled by pirates, existing outside of the law. The history of Haiti and the ‘pirate utopia’ carries in its wake the unshackling of the first slave nation; a short lived freedom with bittersweet consequences.

The city is a free marketplace – an ongoing route of people selling bric-a-brac in ad-hoc stalls set up next to the trash piled up in corners, rotting in gutters and streams (figure 06). A distinction between discarded paraphernalia and rotting trash is fatras: this Kréyol word is a sub-category for compost waste and other unusable organic matter.

Figure 6: La Sante Pharmacy, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

Figure 7: Grace Divine tailoring establishment, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

Almost every shop sign has in its title a profound promise on a painted insignia, highlighting potential for luck, chance, fortune, paradise, spirit, grace and the divine (figures 6-7). Contemplating the auguries that arise from the debris and materialize in the street in daily life in Haiti is overwhelming. I couldn’t possibly solve the plethora of riddles placed before me by these tricksters who revel in life, and laugh at death.

In the local cemetery, as well as tombs, there is prostitution (figure 8). Many grave spaces are rented for a short period; after this, decaying corpses are removed, and coffins cremated - others find their ways into the hands of Atis Resistanz.

Figure 8: Prostitute in Cemetery, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

To get to the Ghetto Biennale, I travelled from Tasmania – via New Zealand, Los Angeles and Miami – before arriving in Haiti. Each leg was part of a spiritual passage, not unlike entering the Labyrinth of the World, a parable by Jan Amos Comenius (1669). This novel is narrated by a pilgrim wandering through a labyrinth with two guides, Searchall Ubiquitous (allegory of human curiosity and longing for knowledge), and Delusion (allegory of indolent adopting of conventional and shallow thoughts). People in this realm wear masks, which makes it difficult to perceive where they are going or what they really mean. The guides attempt to direct the pilgrim through the labyrinth. Each turn, each stumble triggers confusion, comprehension or insight for the pilgrim. The fact I was embarking upon a comparable type of pilgrimage became even more apparent, as at each stage of my journey to Haiti I was required by powers beyond my control to surrender some of my possessions: during transit much of my custom-built electronic equipment – performance tools that generate and mutate live sound – which I had packed in order to make an artwork for the biennale, were confiscated. Therefore, on arrival I arrived without my usual toolkit - unmasked. Moreover, the Grand Rue appeared to me as a labyrinth filled with talismanic charms and paraphernalia that was mainly crafted from remnants of domestic items and industrial waste.

Figure 9: Child of Atis Resistanz, Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

On meeting the members of Atis Resistanz we negotiated via a mix of gestures, broken English and Kréyol. I was particularly drawn to the children as they would enthusiastically show me their work and lead me through the narrow labyrinthine alleys adjacent to their homes. Mutual excitement helped the communication along.

Amongst the chaos, I would muse over my next step. Delving deep into my inner vaults I wondered what could I meaningfully bring to this anomalous event? That is, apart from the small number of battery-operated amusements and hand-held vocoders that thankfully were not confiscated on the journey to the slum in the Grand Rue (figure 9). I was overwhelmed to see the proliferation of bizarre syncretic juxtapositions and paraphernalia of Atis Resistanz jam-packed into every nook and cranny of their homes (figures 10-11).

This place attracted me by instinct rather than by choice...

Figure 10: Child of Atis Resistanz, Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

Figure 11: Children's Gallery at Atis Resistanz, Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

Returning each day to the Grand Rue I eventually began to scavenge for wood scraps in order to make a version of a percussion folk instrument, the Australian lagerphone (figures 12-13). Things began to take their own shape.

Figure 12: Making lagerphone in Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

Figure 13: Getting ready to jam with lagerphones in Grand Rue with Children's Atis Resistanz, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

Many of us eventually began to jam, and came to familiarise ourselves with a basic tune that had emerged in our collaboration (see figure 13).

Figure 14: Promenade through the Ghetto Biennale Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

Together, the Children of Atis Resistanz and I crafted a performance. Waving red and white danger tape, old wood embedded with nails and beer bottle tops, cheering we promenaded through the opening of the Ghetto Biennale (figure 14 and click for Ghetto Promenade video).

02 A used black oil container

The Ghetto Biennale was held in a designated Red Zone (Savage 491) and the United Nations military presence was evident (figure 15). It was also reported and documented by the mainstream media (figure 16).

Figure 15: United Nations Presence in Grand Rue Red Zone, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

Figure 16: Ghetto Biennale Press Conference 2009, Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

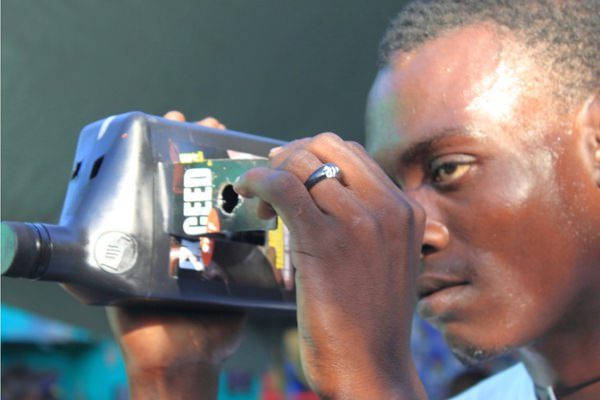

But most noteworthy –a children’s film crew from Atis Resistanz, filmed the event and called themselves from this day TeleGhetto. In a curious way they mirrored privileged international visitors with their digital cameras and mobile devices (figure 17). Having an archival impulse TeleGhetto took footage of all the happenings using a small black oil-container fabricated into a HD video camera with pop out viewer screen and microphones made of plastic and silver gaffer tape (figure 18). TeleGhetto interviewed the Haitian Minister of Culture attending the event; she, with her entire suite of bodyguards, played along. This particular black box oil container was engaged by the operator and those being filmed in the same way a typical hand held video camera is designed to be used, however the computational machinery inside the device was entirely absent.

Figure 17: Racine Polycarpe mirroring Bill Drummond with a Black Oil Container Device at Ghetto Biennale Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

Figure 18: TeleGhetto 'filming’ Ghetto Biennale Press Conference 2009, Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

Such an act opened out the possibility of a black container – as both a black box and a new prospect - from the simple binary illustration of the haves and the have-nots. It transcended the first life of a simple recycled oil container into an enchanted self-performing object. The magical parable concealed within the broken object now pointed towards a new possibility; the user then has to reconsider their engagement with the tool as an object, repair it, replace it, or change their relationship to it. A used black oil container transcended its customary role, it became more than a prop but a tool for recording, surveillance and resistance and charged with a multitude of other possibilities. The oil container did not have a real video camera embedded within it. Therefore, it was iconoclastic, dodgy, humorous, and predictably unreliable; but in that unreliability TeleGhetto emerged as neither fixed nor fictional but instead what could be characterised as an experiential satire, a critical playful prototype. Hence, the alchemist's ultimate dream – the transmutation of base metals into precious ones – is also the transformation of trash into treasures.

Figure 19: TeleGhetto creating a Temporary Autonomous ZONE AT Ghetto Biennale Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

What is also notable when the oil container black box is altered by the camera man performing with this salvaged vessel as if it is a recording devise, it has an embodied affect upon all participants – the people whom are in the frame and those whom hold the devise and frame the shot. This is evident in figures 17 – 20, we can observe the camera operator’s body responding in a definite manner (the intent focus of the eyes, the direct movements of the arm and the entire purpose of the body gestalt in action). Such an intersubjective experience has a transforming effect, the apparatus of the black box oil container makes people behave in novel ways - faces turn towards it, people speak and act in formal ways according to their role their entire body performs and turns ‘on’ as if being viewed and broadcast by a remote presence or audience - allowing insight into the immediate transformative power of an object that brings one into being.

Louco, one of the main elders of Atis Resistanz (figure 20) announced, ‘Today, in the midst of all these people, I can sense that the whole world is watching us. I really feel like now I do exist’ (Savage 495).

Figure 20: RIP Destinma ‘Louco’ Pierre Isnel. Atis Resistanz Grand Rue. (A few weeks after this picture Louco was mortally struck by the the catastrophic 2010 Haiti earthquake, widely known to Haitians as Tranblemanntè 12 janvye 2010 nan peyi Ayiti). Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

03 The Black-Box Analogy

I have described how a used black oil container was deployed to open up and out an instantaneous moment in time. This imaginary act gave me an insight into the depth and reach of the machine into the social fabric of everyday life. That said, to activate a black box - a liminal space where the often mysterious and unknown materializes - serves a number of functions. The black box is a visually and conceptually weighted term in theatre, science and technology; it can also be used in a social sense as applied to the cultural perception of technology. The early use of the term in this sense is by Bruno Latour (1987), whose work later helped establish the influential field of Science and Technology Studies (STS). Alternatively, manipulating a black box with light, or having a complete ‘black-out’ in the black box of the stage, is often an aspiration for a theatre maker. The principle of a blacked out space in order to stage – in darkness – enchanting luminous games is often one of the crucial features of a performance space for performing artists.

In contrast to make transparent by opening up and understanding a black box is often the objective of a critically minded artist, hacker or maker who questions the input and output characteristics of it. This point is made by a community of practitioners and advocates such as The Critical Engineering Working Group (Oliver, Savičić and Vasiliev 2016) made up of technologists and artists who view the opening up of a computer system’s black box as an exploit, the most desirable form of exposure. In their manifesto they state:

The Critical Engineer observes the space between the production and consumption of technology. Acting rapidly to changes in this space, the Critical Engineer serves to expose moments of imbalance and deception.

It is often the case that many black-box consumer devices cannot be opened to customise or modify beyond superficial user settings which only allow features to be used in certain limited ways. A standard commercial example is the application programming interface (API) provided by Apple for the iPhone or iPad. To modify it will void the warranty or often the machine may simply shut itself down. In the future, along the same lines as The Critical Engineer Working Group, I also advocate that such ‘defective by design’ strategies of commercial interfaces should be abandoned as an impediment to human understanding. For instance, when one tampers or ‘jail breaks’ a mobile phone device in order to have full control over the hardware and software functions, shutdown is an undesirable consequence where the electronics gadget becomes ‘bricked’. This is an anathema for the Critical Engineer and related practitioners.

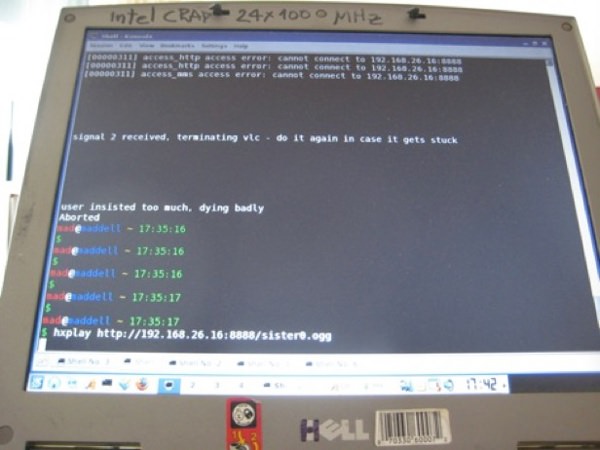

Another appealing concurrence is the somewhat paradoxical notion of the ‘deceptive’ theatrical nature of the ‘black box’ and the (traditionally) black console or ‘shell’ of the computer terminal; such terminals are used for the operation of code as a series of interrelated programs (figure 21). In view of these multifaceted instances, Eugene Thacker writes:

…the black box serves as a kind of allegory of individuation. At once engineered and yet completely mysterious, the black box of individuation functions as a crucial link between the life that is already known and the life that is unknown (or not-yet-known). (86-87)

In this way, a used black oil container deployed by the Haitian makers was a particular not-yet-known moment and a standpoint that was articulated in action. I would go as far to say that TeleGhetto Haiti’s performance with the used oil bottle black box served ‘to expose moments of imbalance and deception’ as the ‘Critical engineer working group’ outlines as one of their tenents.

Figure 21: A typical computer console. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

The black box of the computer console should not be considered as self-contained or static, as besides a myriad of local processes that may be running simultaneously, the computer unit could also be enacting remote processes on other black boxes (computers); which further infers a temporal mode of engagement. This idea finds correspondence with a form of ritual where one plunges into differing depths of awareness and meaning. Such syncretic approaches to material such as a black box, have an interchangeability that renders the specificity of traditional approaches and reception secondary. They reveal the power of subjective approaches and how modding apparatuses can arouse social reflection and alternate participation and shift ones’ conception of technology but also of its embodied reach into our everyday life. Inexplicable syncretic juxtapositions such as the used oil container turned by an action into a broadcasting tool and related performance are forms of abstract thinking which manipulate our perception in regards to how we relate to objects in the world. When arranged as an assemblage primarily to be considered, not through the lens of pragmatism and function, but through the lens of aesthetics, the exuberance this paraphernalia can potentially cause engenders a sacrificial destruction of utility. This could be seen as a paradox in this observation of the black box oil container. On the one hand, the matter-of-fact demystification of technology; on the other, complexity, splendor over function when an action is treasured, because what is provoked and highlighted is the discrepancy between readymade technology and the speculations we project on to the apparatus

Or in other words the ‘space between the production and consumption of technology (Oliver, Savičić and Vasiliev 2016)’.

Figure 22: Czechoslovak Radio 1968 (1969); brick, glue, sulphur; unlimited multiple, by Tamás St. Turba Photo: Turba / International Parallel Union of Telecommunications (IPUT) Archives.

A similar instance of this kind of action: a brick, which has an assigned utilitarian reality, was used ‘conceptually’ as a brick radio in an act of resistance by the people of Czechoslovakia when invaded by Soviet army in 1968 (figure 22). The brick didn’t actually have a functional antenna in material reality, but as people were prohibited by military law from listening to radio broadcasts, they started to allegorically attaching antennas to bricks, and some even painting dials on them, as a sign of protest, responding to the repression of political reforms through creative means. However, in a simple act of make believe people pretended to listen to them, and although they were useless as a communication device, they were continuously confiscated by the military. Fosco Lucarelli describes how ‘although they were useless as a communication device, they were continuously confiscated by the Soviet Army.’ This perceptual shift in relation to an object represents, for ‘Tamás St. Turba (poet, musician, and performance and Fluxus non-artist), the mutation of socialist realism into neo-socialist realism: a non-art art for and by all (Lucarelli 2016)’. Some people would tactically cover the bricks with sulphur - an ingredient of gunpowder, in which I speculate was a statement that the brick was an imaginary transmission apparatus (via communication devise as a radio), but also definitely a potential armament (when it becomes an object propelled through the air, especially one thrown as a weapon). In this particular instance, this brick is comparable to the castoff black oil container, both are former utilitarian objects that have been transmutated into a speculative and operative marvel by performative actions of the users.

04 Obscurely Stylish Reason Friday, Forgotten Saturday…

I became freshly aware of a situation to which I had grown oblivious; that in a modern industrial culture the artists constitute, in fact, an “Ethnic group,” subject to the full “native” treatment. We too are exhibited as touristic curiosities on Monday, extolled as a culture on Tuesday, denounced as immoral and unsanitary on Wednesday, reinstated for scientific study Thursday, feasted for some obscurely stylish reason Friday, forgotten Saturday, revisited as picturesque Sunday.

We too are misrepresented by professional appreciators and subjected to spiritual imperialism…My own ordeal as an “artist-native” in the industrial culture made it impossible for me to be guilty of similar effronteries towards the Haitian peasants.- Maya Deren

TeleGhetto’s use of the oil container playfully tested the very limits of implied rule-based systems and unravelled the traditional theatrical dynamic between performer, object and audience. The urge to broadcast themselves to the world was applied. That is, a used rectangular black plastic oil container, transformed into a video camera, provided insight into the role of a black box apparatus and the power of a playful dream, a comic fiction and even an educative influence. As a result, usual social stratifications and other limiting divisions were transcended, fulfilling (and thrilling) the aspirations of those that experienced the moment.

TeleGhetto’s attempt at filming from an ‘oil container’ harnesses a similar reappropriation method as the ‘brick radio’ through a type of evasion. Haitians historically have encoded messages in Vodou drumbeats, a means of communication. The encoded drumbeats would have provided confidentiality and integrity for the data exchanged and encrypted and helped the slaves overthrow their colonial rulers. The Haitian revolution was an exploit of an otherwise closed system of control through the use of cyphers (Cosentino 25–55). The suppression of the religious practices of the non-Christian members of the colony led to the manifestation of the syncretic form Vodou, which in turn challenged the closed system of French colonial authority. The drums could be sounded in public and played without fear or risk as those without the knowledge of the cypher itself heard not a message but merely a drumbeat. Performative actions such as these can transform objects and offer an insight into and an elaboration of aesthetic processes.

A plastic oil container became a make-believe video camera – a prop transcending its customary role – and manifested out of a conscious attempt to manipulate a consequence. This particular black box became a focal point and reminded us of the power of the imagination that is accessible by any one of us. Intention was directed and pressed into this inanimate object for the communal use of playful mirroring by building upon and capturing an ephemeral moment. The play upon the surveillance object by its experiential use reshaped the material world and produced new fields of meaning and action.

Charms, within both word incantation and as objects, may relate to a pact between a mortal and a deity. But can charms, talismans or signs really ‘work’ independent of one’s belief set?

People imbue objects with personal connections that vary widely. Depending on cultural context, an object can be experienced as a medium, a container of symbolic content privy to a process, or merely a functional tool. Something that is obviously cast off may not be instantaneously useful, but I often read such hand-me-downs as inexpressible gestures or as omens to be deciphered. Science fiction writer Philip K. Dick pronounces ‘…the clue lies there…symbols of the divine show up in our world initially at the trash stratum’ (Davis 303). Political and economic interests continually shape objects, tools, techniques, hardware and software and embed them with meanings and political and cultural agendas. Assemblages of paraphernalia produce a subtle transgressive power that challenges implied notions by providing an insight into distinctive characteristics of the object beyond standard usage for the people whom intermingle with them.

In our endeavor to be meaningful, we limit the set of our potential actions by casting objects and machines into purely utilitarian roles. The exploration of a black box reveals how knowledge of staging and performing are central to a rejection of closed, hierarchical and hence exclusive systems of knowledge. However, the expressive use of the black box never completely justifies its procedures, a meaning of which we can never be sure has escaped us. This echoes the paradox of the discarded black plastic rectangular oil container that appeared and blossomed in the ghetto of Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. The rules of the mundane gave way to the demands of elevated states examined through the modified lens of the oil container.

This small incident evoked a tremor for a considerable directional shift in my own future pursuits. That is to say, it altered my affirmative orientation upon free-software methodologies and their relationship to contemporary art, to a much broader conversation around aesthetics of performance tools and their historical and political antecedents.

Suffice to say this ambivalent notion of deception and forgery that communicated at the crossroads between life and death with a more-than-human world was affecting. I became even wearier of the tedious divisions between the states of being dead and alive. It was a state, not unlike what the Lakou dance group, co-conceived by Hermane Desorme, who performed Zonbi Zonbi at the Ghetto Biennale, claimed: ‘Nou tout se Zonbi!’ (We are all Zombie!) It’s not only just after death that a person becomes a zombie - many people become zombies without even knowing it. Jalal Toufic, a Lebanese philosopher reflects upon phenomena of death before dying:

Were you to die physically before me (who has already died before dying), becoming in the undead realm a superposition of possibilities, and I opted for forgery rather than history, I would inflect what will have happened to you, the late. (22)

I started to realize that there must be a difference between this life and one that longs only for a poetic (utopian) life. Affecting, because previously I had always been attracted by the allure of pirate utopias (figure 24), what Hakim Bay calls ‘temporary autonomous zone’ (TAZ),

We are looking for ‘spaces’ (geographic, social, cultural, imaginary) with potential to flower as autonomous zones...times in which these spaces are relatively open either through neglect on the part of the State or because they have somehow escaped notice by the mapmakers, or for whatever reason. Psychotopology is the art of dowsing for potential TAZs. (101)

What remains the most lucid for me now is a most difficult and cherished thing: how rare experiences gain importance in daily life. But if these reflections do not permeate daily life including its vexations, then the experience is in danger of being merely an ideal, an exotic utopian projection; undesirable in any way other than as spectacle. The cryptic writings of John Amos Comenius in his novel, Labyrinth of the World (1669, V) continue to evoke manifold parallels to my pilgrimage. Comparably in Shakespeare’s The Tempest, a labyrinth is set up by Prospero to test the motives of his adversaries. After his dominion is established over others by renouncing magic through his noble pursuit of reason, Prospero pushes one more threshold into wisdom.

In cultural terms, these rituals are ‘rites of intensification’ (Turner 131) that are a temporary dissolution of the established order, but which actually embed and reinforce values and norms. In this way, the process of dissolution simply reifies the position of the master and the slave when the biennale (or carnival) is over. My experience reveals how technical consideration of the apparatus as both tool and a theatrical medium and the condition in which human beings are located – an open-ended, ever variable trajectory – can serve to unwrap fixed and regulated systems and circumvent hierarchical notions we place on objects within the consumer world and beyond. Aesthetically exploiting these otherwise closed systems, techné pays heed to those dimensions that are not governed by the imperatives of use and efficiency.

I have tracked a journey from stumbling out from an airplane into the realm of a labyrinth in the Grand Rue slum in Port-au-Prince. I found myself twisted in a mortal coil of bedsprings, beer bottle tops, and discarded components. A surveillance device, under the guise of an oil container, led me to an enigmatic parable from the seventeenth century, and with this I navigated my way out through the maze, to discover myself contemplating and substantiating the power of suspending one’s disbelief (figure 25/26). From this position, I evaluated how the objects created by our embodied thought shift in tandem with the technologies that in return engage our senses, our inner veracity.

Figure 23: Child of Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude.

I do not wish to approach these things with a rational state of mind, but I want to understand them as something to which one is susceptible. I become even more predisposed to clues, emblems, myths and reading around myself as if every moment could be opened up for divination. I find myself in my former environment talking about things that I felt completely alienated from. That is, normal things, such as: what do I need to do to get a kernel update from a remote server mirror on my computer through a university proxy server.

As I am writing I realize it is not about memory, and trying to be accurate. There is no separation between now and then; an infinite continuum spirals through generations. Everything is still there, ‘whose beginning is not, nor end cannot be’ (Casaubon)

In Haiti the drum beat plays day and night, but is it now a hollow form?

A scenario comes to mind: On the shores of where the shipwreck of Global surveillance has cast us, I pick up pieces of the wreckage and play with them, at least until I find the wand of Cinderella's Fairy Godmother, Circe.

Figures 24-25: Self-Portrait with Milou (Jean Muller Milord). Ghetto Biennale Grand Rue, Port-au-Prince. Photo: Nancy Mauro-Flude

Works Cited

Bay, Hakim. TAZ: The Temporary Autonomous Zone, Ontological Anarchy, Poetic Terrorism. New York: Autonomedia New Autonomy Series,1990. Print.

Casaubon, M. A True and Faithful Relation of What Passed between Dr. John Dee (A Mathematician of Great Fame in Q.Eliz. and King James their Reigns) and Some Spirits: Tending (had it Succeeded) To a General Alteration of most States and Kingdomes in the World. M Casaubon, D.D. Ed. London, 1659. Berkeley: Golem Media, 2008. Print.

Cosentino, DJ. “Introduction: Imagine Heaven.” Sacred Arts of Haitian Vodou. Los Angeles: UCLA Fowler Museum of Cultural History. 1995. 25–55. Print.

Comenius, Jan Amos. Labyrinth of the World and Paradise of the Heart. 1669. 20 March, 2016 <http://www.labyrint.cz/en/>. Web.

Davis, E. “Philip K. Dick: Speaking with the Dead.” Follow for Now: Interviews with Friends and Heroes. Ed. R Christopher. Seattle: Well-Red Bear. 2006. 301-312. Print.

Deren, Maya. Divine Horsemen: The Living Gods of Haiti. McPherson: New York. 1970. Print.

Gordon, Leah. "What happens when first world art rubs up against third world art? Does it bleed?." Message to Nancy Mauro-Flude. 20 August. 2009. Email.

Latour, Bruno. Science in action: How to follow scientists and engineers through society, Harvard University Press: Cambridge. 1987. Print.

Lucarelli, Fosco. “Czechoslovak Radio 1968, by Tamás St. Turba” 1 August 2012. dOCUMENTA 13.14 January 2016 <http://socks-studio.com/2012/08/01/documenta-13-czechoslovak-radio-1968-by-tamas-st-turba/>. Web.

Moberly, Tracey. “Haiti Ghetto Biennale.” Jan 28, 2010. Dazed and Confused 13 March 2015 <http://www.dazeddigital.com/artsandculture/article/6425/1/haiti-ghetto-biennale>. Web.

Oliver, Julian; Savičić, Gordan and Vasiliev, Danja. The Critical Engineering Manifesto. 2011-2016. The Critical Engineering Working Group. 12 July 2016. < https://criticalengineering.org/>. Web.

Reid, Jim. “Money to Burn.” 25 September 1994. The Observer. 15 March 2016 <http://www.libraryofmu.org/display-resource.php?id=387>. Print.

Savage, Polly. “The Germ of the Future? Ghetto Biennale: Port au Prince” Third Text: Critical Perspectives on Contemporary Art and Culture. 24.4 (2010): 491-495. Print.

Thacker, Eugene. “Alberto Toscano, the Theatre of Production: Philosophy and Individuation between Kant and Deleuze.” Parrhesia. 7 (2006): 86-91. Print.

Toufic, Jalal. Over-Sensitivity. Beirut: Forthcoming Books: 2009. Print.

Turner, Victor. The Ritual Process: Structure and Anti-Structure. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Co.1969. Print.