Field of Mars: Remains of the Commons

by VANESSA BERRY

- View Vanessa Berry's Biography

Vanessa Berry is a writer, artist and psychogeographer based in Sydney.

Field of Mars: Remains of the Commons

Vanessa Berry

The field is sustaining from below, as it were. It stands under specific actions as a matrix of support, helping them to cohere as specific events or as a concatenated series of events occurring just here and nowhere else. (Casey 199)

Fields, like maps, are often used as spatial metaphors. The field is a metaphor of enclosure, indicating boundaries which contain a space and include details, events and identities. This essay is an experiment in negotiating a place literally designated a field — the Field of Mars reserve in northern Sydney — and the relationship of its physical, imagined, and archival presences. In demonstrating the traversal of the Field of Mars, a process involving multiple trajectories and interpretations, it aims to also draw attention to qualities of the field as a metaphorical space.

In writing of the relationship of place and memory Edward S. Casey describes the "field" as underlying "a concatenated series of events occurring just here and nowhere else" (199). The field sustains specificity, particular events that occur in this place only. Using this definition the Field of Mars can be understood as a cohesive force for the gathering of specific topographical and physical features, human and non-human presences, and events in the form of knowledge, memories and experiences. These elements cohere through levels of interpretation and representation. Casey uses concatenation, a metaphor of linkage, to suggest this process of coherence.

One method of concatenation comes through archival research and the gathering of information about past events and practices. The first section of this essay uses archival sources to understand the Field of Mars as a place of resistance which has retained this identity amid the growing suburbanisation of its surroundings. This formulation of the Field of Mars as an imagined space informs my engagement with it in the second section, a descriptive narrative of walking the reserve.

Together these investigations explore the field as an enclosing or containing entity and a space of negotiation. While this negotiation can take a linear narrative form, such as a chronology (a historical timeline, a walk), it is also open to expanded and contingent narratives. While this is a textual traversal of the Field of Mars, it also engages with the non-linear, spatial readings that can occur through mapping. In her work on mapping and metaphor Peta Mitchell suggests the map as a metaphor for "the negotiation (physical and cognitive) required in order to derive meaning from our environment" (3) and it is with this idea in mind the following investigation of the Field of Mars is presented.

Field of Mars

After a stretch of local shops the road curves left and narrows. Houses line the cliff edge above and by the roadside trees have been overtaken by kudzu vines, transforming them into amorphous green monsters. At the roundabout at the bottom of the hill is a sign announcing this area as the Field of Mars.

This place with the unusual name is one where the atmosphere shifts. The pattern of streets and houses pauses, giving over to bushland, and this interlude reveals the rise and fall of the terrain. Sydney's topography produces many such moments, where the tussle between the land and what is made of it determines the arc of the road or the eccentric shape of a boundary.

The Field of Mars is most often experienced through car windows, on the drive between Gladesville and North Ryde. Travelling by car often limits a sense of connection to a place's physicality, but here the road’s curves bring with them a sense of the shape of the land. The road continues with the rock face on one side and bushland on the other, for a moment folding the cars into the landscape as they pass through it.

Like so many Australian place names "Field of Mars" is grafted from elsewhere. Sydney’s names often commemorate people and places far removed: the city's name itself has been traced back to a corruption of St. Denis (Park 3). Among its suburbs are versions of Beverly Hills, Sydenham and Avalon, each an antipodean transposition: glamorous celebrity enclave to postwar residential suburb; outer London borough to inner-Sydney light industrial area; mythical island to northern suburbs beach.

The Field of Mars was named so in 1792, in association with Governor Phillip's land grants to soldiers in the area around the Lane Cove River. Its twin was an area of granted land on the southern side of the harbour named the Field of Concord, it is suggested, as a peaceful counterbalance to the martial allusions of the Field of Mars (Stacey 2). Mars the god of war, and the Field of Mars the Ancient Roman site where the army trained and exercised: its naming was commemorative, aspirational, without reference to the land itself.

The land named the Field of Mars was a region of forest and waterways, country of the Wallumedegal people. Their name was derived from wallumai, the snapper fish once found in plentiful numbers in the rivers here. Within a year of British invasion many Wallumedegal, along with others from the group of Sydney clans – the Cadigal, Cameragal, Wangal and Burramattagal - died from smallpox. The home for the surviving members of the northern clans became nearby Kissing Point on the Parramatta River (Smith). Their country was increasingly distributed among the settlers, claimed and mapped, boundaries drawn, subject to new laws of use and ownership. As British settlers felled the Field of Mars forests they recorded the size of the enormous trees, up to 300 feet tall, with trunks as wide as 40 feet (Levi 52).

A Forest Clearing in New South Wales: Tyrrel Photographic Collection/Powerhouse Museum.

In 1804 an area of 6000 acres of the Field of Mars was decreed as a common. The common stretched from what is now Hunters Hill, through Ryde to Pennant Hills, incorporating a large tract of forest around the Lane Cove River. It was intended as a resource for small settlers, a place for them to graze their livestock and collect firewood, to supplement their farming practices. The common was one of a number declared at the time around Sydney, with many more across New South Wales, where in the nineteenth century there was over a million acres of common land (Maddison 181).

Increasingly tensions arose between private and public lands. Over decades the Field of Mars became a haven for smugglers, bushrangers and other persons of ill repute. In an 1862 report it was described as "an incubus upon the district" and an impediment to the area’s progress (Heydon quoted in Taylor, 04.11). Nearby landowners complained of the vagrants, timber cutters and runaway sailors who made the common their home. Even in its early years the Field of Mars had been associated with dangerous characters. In 1809 the Sydney Gazette reported on a dispute between two women at a market concerning stall locations, which produced “a storm of words” before an “athletic termination”. The Gazette describes the women engaging in seven rounds of surprisingly adept boxing and announced that, fittingly, the women were residents of the Field of Mars (Levi 36).

Despite the protests of the locals who used the common for respectable purposes, in 1874 the majority of it was sold to private buyers, eventually to become residential suburbs. From this, a small island of land set aside for public recreation — now a nature reserve and a cemetery - forms the remnant of the once vast Field of Mars common.

This collection of stories can be expanded and contracted, and positioned alongside the contemporary incarnation of the Field of Mars as a nature reserve amid suburbia. The narratives I collect and present here become a field in themselves, a topography of contours and tributaries. The narrative field contains Aboriginal stories and colonial ones, stories of country, of law and lawlessness, of tensions between public and private that have continued as long as it has been known as the Field of Mars.

If the Field of Mars had a different name it would be unlikely to suggest itself so readily as a place to think with. "Field", as a metaphor of enclosure, suggests a separation between the field and whatever surrounds it, focussing attention on what is within its boundaries. In literal terms "Field of Mars" draws attention to the materiality of the place: although it is named as a field, it is not the neatly circumscribed patch of meadow that the term most readily suggests. Glimpsed through the car window when driving by there is little clue to what kind of place the Field of Mars might be. Under a high concrete aqueduct is a carpark and a track leading into the bushland. To gain a sense of this place it is necessary to stop and to physically enter it, to follow its paths.

Turning Off

For all the times I'd driven past and wondered about the Field of Mars I had never actually stopped there. Traversing the suburbs by car sustains these distant, drive-past relationships with places. Driving comes with momentum, a focus on motion that can be hard to arrest without reason. Even acting on the intention to visit "sometime" it was only at the last moment I pushed the indicator and turned off the road.

Entering the reserve I follow the path towards Buffalo Creek, an area of saltmarsh planted with mangroves. The sound of traffic and aircraft overhead forms a disjointed clamour. I watch a jet move through the sky, imagining I am inside it and looking down from a window. This view from above I know well, how the bushland appears as dark green tendrils, extending around and into the built-up areas, marking the city's edges.

In front of the casuarina trees that grow beside the creek a bearded water dragon is arrested in an alert, startled pose, jaws clenched around a meaty scrap. The lizard and I watch each other for a minute, neither moving, before I break the détente and keep walking. Around the corner a cluster of schoolkids group around a tree, hollering in delight at having found a huntsman spider. Their task is to count the animals they see on their excursion to the reserve, and they yell out in a chorus the category for their latest find: Creepy crawlies. In this moment the Field of Mars becomes an educational space, one for children's gentle initiation to a non-human world.

The schoolchildren have their research methods and I have mine: I select a path and start walking. I choose walking as a way of experiencing the field and gathering knowledge. The potentials of walking as an ethnographic research method and method of arts practice has become increasingly realised, as walking is defined as a practice "creating new embodied ways of knowing and producing scholarly narrative" (Pink et al. 1). In writing of artwork and literature based in walking, Karen O'Rourke describes the "walk as gestalt" (71). In these works the walk takes shape as a combination of its features — the topography, the artist's embodied experience - and the form of its presentation. In walking-based creative work the walk retains its specificity as an experience. "They [walks] can be repeated by others," she writes, "but then they would become something else" (72). The narrative of walking a place is both a narrative of embodied experience and narrative of the place.

Considering the field as a metaphor of enclosure, the walk can be thought of as a practice which operates within it, a method of negotiating its territory. As a method of traversing the field it is at once specific and with the potential to make connections to networks of stories, among them those of ecology, history and memory.

The Field and What I Found There

I choose the path that zigzags upwards and climb up over the tree roots and rocks that form a haphazard staircase. Then the track flattens out and continues through a forest of bloodwoods, banksias and scribbly gums, the inscriptions on the trunks a mysterious cursive. After the overnight rain the air is fresh with the resin scent of eucalyptus. The rhythm of walking soon overtakes my thoughts and I settle into its pattern, step after step, detail after detail: a cluster of mountain devil seed pods, a pool of sticky red sap, termite mounds in the tree branches repurposed into birds' nests.

The path continues through an open, grassy area, then plunges into a thicket of vines and privet. The crash of my footsteps sends the skinks basking on the path darting back into the undergrowth. The privet flowers make the air ticklish with pollen and it feels like a childhood wilderness in here among the tangles of blackberry and lantana, a suburban fort of prickles and scratches.

At the end of the path and the edge of the reserve a long, black snake is curled up in a patch of dry grass. I follow its loops with my eyes until I reach its neat head and bright eye. It's a red-bellied black snake, a creature the continual subject of parental warnings when I set off into the long grass of our acreage as a child. Back then I had carefully watched out for them but never actually encountered one. I inch forward and it slithers away, a black ribbon disappearing into the grass.

I am on the western boundary of the reserve now and walk along the footpath until I come to the cemetery gates. This area was part of the public land set aside from the sale of the common in the late 19th century and is almost encircled by the bushland. At the gate is what was once a bus shelter but now a faded painted sign announces it as a flower stall. It opens on weekends to dispense bunches of roses and carnations to cemetery visitors.

The cemetery has the crowded stillness of all burial grounds, an accumulation of presences and absences. The graves extend across undulating terrain, in sections divided by roads lined with palm trees and conifers. In the older parts of the cemetery the monuments are cracked and weathered, a patchwork scene of stone, tile and concrete. I collect names from the headstones: Sutherland Innes Sloss; Mary Jane Flowerdew, Violet Ethel Blagbrough. There are graves of nuns, of soldiers and of priests, a row of family vaults with epitaphs in Italian, rows of inscribed stones under paperbark trees for children who lived for two days or one hour.

Like the nature reserve the cemetery is still a kind of common, a place open for wandering and contemplation. It is a collection of lives (John William Strange, Lorna Alice Wildman) and countries (born Sicily, born Glasgow, served in Tobruk), inscriptions (dear father, loved daughter, fell asleep, resting) and decorations (stone urns and clam shells, vases and ceramic swans). As I travel through this landscape a groundskeepers' lawnmower keeps up a persistent whine, cemeteries being places of maintenance along with memorial.

On the northern edge of the cemetery I return to the bushland, following the track into the thin strip of forest between the cemetery and the backyards of the houses on Finch Road. Like many of the surrounding streets it was named after an actor. Developed in the 1950s as the Dress Circle Estate, these East Ryde streets were named after Australian screen and stage stars (Hood and Phippen). The stars included Nellie Melba, Gladys Moncrieff and in this case, Peter Finch, known best for his performance as the newsreader in Network who urges viewers to open the window and yell "I'm mad as hell and I'm not going to take it anymore!".

The sounds of kids playing carries over from Finch Road backyards. Visible through the trees is the sharp blue of an inground pool floating with bright inflatable toys. Then the track leads towards the centre of the reserve and the voices fade, the houses no longer visible. I walk over a soft patch of she-oak needles as an olive backed oriole wavers its eponymous call from a tree above: orry orry oriole, orry orry oriole. The path then widens into a rock ledge, believed to have been a Wallumedegal meeting place. The sudden clearing interrupts the track, an expanse of sandstone with patches of pale lichen across it, a moment of pause.

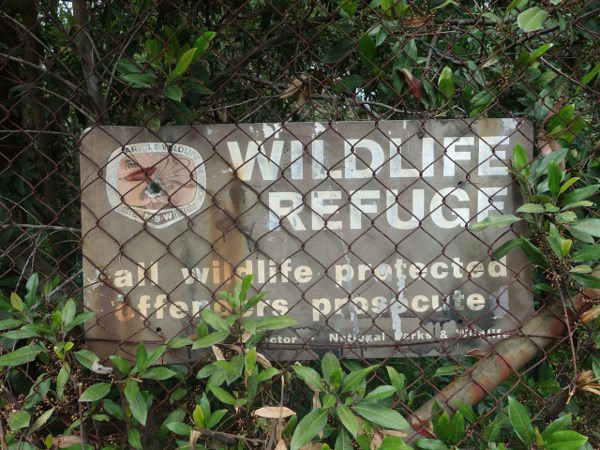

Walking in the Field of Mars is a journey of clearings and enclosures, a negotiation of environments and of the events embedded in them. Some of the events leave traces, like the fire-blackened trunks of trees, axe grinding grooves in the rocks, or the privet and lantana overgrown from suburban gardens. The field is a place of traversal for birds and creatures, and for the humans who follow its paths. It is a sustaining place, a refuge for animals and plants. For humans it is a respite from the urban pattern and a remnant of shared space in a city increasingly crowded, increasingly privatised.

The visitors' centre at the end of the walking tracks is a squat brick building with tables of pamphlets, an urn on the boil for tea and coffee and a container of Milk Arrowroots. Here I flip through a photo album with yellowed newspaper articles that chart the history of successes and threats: the tip, the north western expressway, vandals, the expanding cemetery, and in 1977 a runaway stag with antlers one metre wide which led police and a vet with a tranquiliser gun on a five hour chase through the bushland.

The school excursion rabble has long since moved on, but as I walk back out towards the road the lizard is still there by the creek, in the same position as an hour before. It’s the sentinel of the Field of Mars, a dragon at the gate, guarding this place and all its stories.

The Field of Mars exists as a space open to physical and narrative possibilities and negotiations. As a break in the suburban order it connects with stories that are often obscured in such environments, such as those of ecology and the tension between urban settlement and public land. By this exercise in walking/writing I have negotiated this place physically, through archives and through imagination, experiencing and producing a chain of events within the boundaries of the field, and of my experience and knowledge.

As a spatial metaphor the field is an enclosing entity that requires traversal. As with the Field of Mars, the journeys and pathways taken across the field have endless variations, but are a necessary negotiation that takes place, whenever and wherever the field is encountered.

All photographs are by the author, unless specified.

References

Casey, Edward S. Remembering: A Phenomenological Study. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000.

Maddison, Ben. "'A Kind of Joy-Bell': Common Land, Wage Work and the Eight Hours Movement in Nineteenth Century N.S.W." The Time of Their Lives: The Eight Hour Day and Working Life. Ed. Julie Kimber and Peter Love. Melbourne: Australian Society for the Study of Labour History, 2007. 181-196.

Mitchell, Peta. Cartographic Strategies of Postmodernity: The Figure of the Map in Contemporary Theory and Fiction. New York: Routledge, 2013.

O'Rourke, Karen. Walking and Mapping: Artists as Cartographers. Cambridge MA: MIT Press, 2013.

Park, Ruth. The Companion Guide to Sydney. Sydney: Collins, 1973.

Hood, John and Angela Phippen. "East Ryde." In Dictionary of Sydney. Sydney, 2008. Web. Accessed 23 May 2016.

Levi, M.C.I. Wallumetta: A History of Ryde and Its District, 1792-1945. Ryde N.S.W.: Ryde Municipal Council, 1947.

Network. Dir. Sidney Lumet. Perf. Faye Dunaway, William Holden, Peter Finch, Robert Duvall. Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer. 1976.

Pink, Sarah et al. "Walking Across Disciplines: From Ethnography to Arts Practice." Visual Studies, 25.1 (2010): 1-7.

Smith, Keith Vincent. Wallumedegal: An Aboriginal History of Ryde. North Ryde, N.S.W.: Community Services Unit, City of Ryde, 2005.

Stacey, A.W. "Some Historical Links between Ryde and Concord." Paper presented at the Concord Historical Society Meeting, 17 June 1975.

Taylor, Jane. "An Incubus Upon the District': Progress, Private Property and the Field of Mars Common." History Australia 7.1 (2010): 04.1-0.4.19.