Making the Story Go Far

by ELLISE BARKLEY

- View Ellise Barkley's Biography

Ellise Barkley is a management and evaluation practitioner specialising in program design, impact, and partnership brokerage in community development, creative arts, education and sustainability.

Making the Story Go Far

by Ellise Barkley

Introduction

Since the beginning of the atomic age -- marked by the first atomic experiments, detonations, and use of nuclear weaponry on civilian populations in the 1940s - artists have responded to the bomb to make sense of, commemorate, and expose the humanitarian and ecological legacies of nuclear weapon testing, use and stockpiling (Jolivette 2014; O'Brian and Borsos 2011; Jacobs 2010). Within the 'art and the bomb' tradition, artists have also utilised the creative arts as a means to --affect social change, in an effort to counter the cultural amnesia that has long surrounded the nuclear age.1 For artists and communities interested in creating impact and understanding the wider implications of their art-making and/or creative works in this arena, the process of evaluation can present both technical and epistemological challenges (Barkley 2016). More broadly in the arts, such as in the domain of community arts evaluation, approaches for how to effectively identify and appraise cultural and arts impact remains highly contested amongst practitioners and scholars (Goldbard 2015; Belfiore and Bennett 2010).2 In the absence of any agreed framework, practitioners wanting to evaluate cultural and arts impact must traverse these challenges on a project-to-project basis, and manage numerous external pressures, such as the often misappropriated orientation by funding agencies towards the quantification of arts impact (MacDowall, Mulligan, Panucci, and Badham 2013).

Framed within the problem of deep-time enquiry for the nuclear age, this essay explores the limitations and opportunities for community arts evaluation in relation to gauging and extending cultural and arts impact. Presented is the original approach to program evaluation developed during the Nuclear Futures Partnership Initiative (herein, Nuclear Futures and the initiative) - a three-year international community arts and cultural development program involving collaboration between artists and atomic survivor communities.3 The initiative produced a multi-arts suite of story-based creative works, and generated extensive program documentation, evaluative outputs, and community-based archival research on Australia's atomic legacies. During the delivery of its community arts evaluation practice, Nuclear Futures also sought to better understand the role of the creative arts in exposing the legacies of the atomic age more broadly.4 One of the compelling (yet ultimately unanswered) questions arising from the arts practice was: What creative artworks and artefacts can endure across the deep-time of the nuclear future, and by what processes--if at all--is this achieved?5 Addressed in this essay are the evaluation-related ramifications of this enquiry, and the emergent methodology employed to conceptualise and appraise the program's impact in order to gain insight into its artistic, social, political, and legacy implications.

In response to the evaluation and legacy goals set for the initiative, Alphaville, together with the Nuclear Futures creative team, devised the READ model-- a participatory and partner-oriented framework for learning, appraisal and dissemination that integrates Reflection, Evaluation, Analysis and Documentation (READ). Presented in this essay are a number of the practice-informed findings arising from the Nuclear Futures experience of designing and testing the READ model, including three emergent strategies relevant for assessing and enhancing cultural and arts impact in the community arts context.6 In doing so, it is argued that the READ approach extended the legacy outcomes of the Nuclear Futures arts practice, via the innovative use of artistic mediums and archival methods to create enduring records of the atomic survivor community stories unearthed over the course of the three-year program.

This essay develops and defends this contention in four parts. First, the futures thinking paradigm underpinning the Nuclear Futures program objective to 'make the story go far' is grounded within the broader discussions of future nuclear heritage. Society's on-going experiments with nuclear materials since the mid Twentieth Century (via uranium mining and transport, nuclear weapons testing, radioactive waste handling, and the releases from 'civil' nuclear installations) have not only impacted people and ecosystems in the past and present, but have also irretrievably colonised a deep future (Brown, Hudson, Barkley, and Arvanitakis 2013). For the Nuclear Futures cohort, applying a futures lens during the community arts translated into several attempts to promote and gauge intergenerational impact, and this influenced the arts practice, promoted innovation in evaluation, and extended the range of program outcomes so far achieved.

Second, the community arts evaluation context from which the READ model arises is briefly examined to highlight the model's relevance as a tested learning and appraisal tool for the field. Of significance, the experiment to design a reliable and reflexive evaluation approach for the Nuclear Futures program resonates the challenges faced by arts and evaluation practitioners more widely, and fits within the debate on effective cultural and arts impact evaluation. Third, the approach adopted by the Nuclear Futures cohort is detailed, the READ model, elaborating on its inter-related strategies for learning and appraisal. Acting as both a formative and summative lens for the program, the READ model broadened the scope and purpose of the evaluative processes implemented (beyond conventional merit-attribution only evaluation), and drew on the ethos and strength of the community arts creative practice. As well as advancing the evaluation practice of the Nuclear Futures cohort, the READ model findings also contribute to the contemporary discourse on cultural value and impact evaluation in the community arts context (Barkley 2016).

In the final section of the essay, three key areas of innovation are identified that progressed Nuclear Futures' legacy goals -- the use of creative documentation, broader analysis via an 'unlocking the academies' approach, and content dissemination via strategic partner organisations for long-term storage and access. The success of these strategies in extending program impact raises new goals for community arts and cultural practitioners, and is an original and socially driven outcome of the READ methodology. The findings are of interest beyond the atomic and community arts contexts, offering methodological design insights for practitioners, activists, evaluators and managers interested in arts impact, community engagement, and legacy-making more broadly.

Thinking of the nuclear future

The Nuclear Futures program sits within a long tradition of artists and communities responding to 'the bomb'. In Australia, in the sixty years since the British-led atomic tests in Western and South Australia, a substantial body of creative work has been generated that reveals diverse community stories of impact and resilience, and a spectrum of political reaction to Australia's secret atomic experiments (Mittman 2016).7 The suite of creative works arising from Nuclear Futures builds on this, to provide a cohesive multi-arts and interdisciplinary response to Australia's atomic history, defined by its cross-cultural collaboration at the community level and inclusion of a register of voices from both Aboriginal and non-Aboriginal atomic survivor communities.8 During 2014-16, some sixteen inter-linked community arts and cultural development projects were delivered via the initiative, in partnership with communities directly affected by the atomic bomb involving participants from Australia, the Marshall Islands, Japan, Kazakhstan and Britain (see Brown 2018 for more about the Nuclear Futures program). The multi-platform artworks produced were provocative, informative, powerful, and nationally significant for the role they played in unearthing, interpreting, and promoting community legacy stories about Australia's largely unknown atomic history.9

Concurrent with Nuclear Futures' objective to make a new round of atomic art using community arts and cultural development processes, was the objective to 'make the story go far' (Alphaville 2015). Formally and informally, the cohort contemplated themes of nuclear impact, how the creative arts might play a role in intergenerational messaging, and the ambiguities of deep future timeframes, which in the case of Maralinga's plutonium-239 contamination is in the magnitude of an estimated 24,000 years (World Nuclear Organisation, 2013). The following reflection provides one example:

Alphabets endure, as do some human-made materials, especially ceramics. Certain monuments, cave paintings, other traces of civilization--we know they can last. And radioactive nuclear materials endure. This makes us think about the long trajectory of human society. What will it be like after many millennia? What are our responsibilities to future societies? And what communications and artefacts could possibly make a bridge to the deep future from where we are now? (Brown et al. 2013, 167)

As the program developed, the creative team explored the question of what artworks and artefacts might endure the nuclear future, and how this might be achieved (if at all). Of interest were legacy artefacts and processes that, at the very least, might extend program impact for the current and/or immediate generations. Not surprisingly, the enquiry into optimising the program's impact (via embedding longevity into the outputs produced) proved a highly compelling yet problematic pursuit.

The type of long-range thinking and futures imagining underpinning the Nuclear Futures creative practice fits within the discipline of futures studies (amongst others), where possible, probable, preferable and wildcard futures are analysed using interdisciplinary methodologies (Slaughter 2002).10 One of the key foundations of the futures studies discipline is the premise that the future is plural, rather than singular, that is, that alternative futures exist (Bell 2002, 1997).11 Over the past 40 years, numerous futures studies projects have attempted to tackle the question of deep-time communication (in more sophisticated and resourced ways than Nuclear Futures' modest ponderings of how to make the story go far). Attempts include the work by the Long Now Foundation to foster thinking that endures 10,000 years, including their project to construct a 60m high clock inside a West Texas mountain, that will tick, chime and play music for 10,000 years; and United States of America (USA) government research, including linguistics and semiotics projects, to imagine communications over millennia in response to the problem of communicating about nuclear waste hazards into the deep future (Long Now Foundation 2015; SNL 1992). While no assured method or modality for deep future communication can be ascertained, one emergent idea is that it will require as a foundation bridging cultural messages across multiple generations, such as via a 'folkloric relay system' with checking points every 250 years (Sebeok 1984; Gaiman 2015; Mars 2014). Debated are the potential visual and/or oral communication methods for achieving this, given that all vestiges of society as we know it -- languages, political boundaries, social structures, technologies, communication systems -- will change profoundly during the deep temporal scale of our nuclear futures (Masco 2006; Galison and Moss 2015).

In Australia, inspiration and insight into successful intergenerational messaging can be drawn from the cultural continuity and transmitted knowledge of the First Nation peoples, the many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Island cultures (some of which are recorded as being over 40,000 years old). Of particular relevance to the broader discussion on deep future communication is the recent research on Australian Aboriginal traditions that challenges the notional limits of orally transmitted knowledge generally accepted within the scientific community (estimated at 500--800 years), and evidences the possibility of accurate storytelling recall from numerous communities around Australia across timeframes of more than 7,000 years (Nunn and Reid 2015).12 While the findings are radical in the scientific context and do not verify the limits of Australian Aboriginal peoples' long-term communication, the research does identify several likely attributes of Aboriginal oral knowledge transmission that have encouraged stories to become culturally embedded across generations. For instance, Nunn and Reid (2015) argue that in Aboriginal storytelling there is an overtly stated focus on the importance of telling stories 'properly', which involves ensuring the accuracy of the story content as well as a focus on story ownership and control--to establish who has the authority to tell a story.13 The storytelling is also supported by a deliberate tracking of teaching responsibilities, where certain kin are tasked with cross-checking that stories are learned and recalled correctly by the learner (Nunn and Reid 2015). Cultural and storytelling protocols such as these are similar to what Rose (2013) refers to as a cross-generational mechanism, those cultural processes necessary for ensuring memories and stories are explicitly passed on in a way that optimises the precision of story replication across successive generations.

For the atomic survivor communities involved with the Nuclear Futures initiative, the quandary of how to make the story go far is of immediate and critical concern as they continue to seek recognition for, and attempt to respond to, the ongoing effects on their peoples and/or land from nuclear weapons testing and use. Six and seven decades on, the remaining eye witnesses carrying forward the stories from affected communities become fewer each year. Communities in Australia, Japan, Britain, and the Marshall Islands for example, face the problem of how to continue to represent and share the important humanitarian and environmental messages arising from their community's atomic experiences, once personal survivor testimonies become no longer possible.14 In Japan, plans for intergenerational messaging of the potent Hibakusha stories from Hiroshima and Nagasaki, have turned to the strategic use of creative methods that utilise both oral and visual storytelling methods.15 The Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation for example, one of the organisations charged with carrying forward Hibakusha messages long into the future, advocates that various modes of creative expression will be needed to prolong atomic storytelling and engage new generations, including the use of image media, literature, paintings and music (Komizo 2013).

Evaluating cultural and arts impact using the READ model

At the Nuclear Futures site of practice, the legacy and impact ideals raised by the intent to make the story go far created a secondary challenge: how to understand the wider implications from efforts to do so, and how this might relate to the effective program evaluation of value and benefit generated for participating communities, partners, and more broadly. Put simply, how would the Nuclear Futures cohort know if they were successful in what they set out to achieve, and gain insight into the artistic, social, political and academic implications of the work? The enquiry into evaluating community arts impact and contemplation of deep future timescales also needed to be grounded in the consideration of the contemporary evaluation trends and debates (arising in the field over the past four decades) that defined the more immediate contextual backdrop to the program, delivery, and appraisal.16 Experimentation with pluralistic evaluative approaches was of interest too, for pursuing the developmental, short-term, and longer-term enquiry goals of the program.

While definitions vary, the Australasian Evaluation Society describes evaluation as encompassing 'the systematic collection and analysis of information to make judgments, usually about the effectiveness, efficiency and/or appropriateness of an activity' (Australasian Evaluation Society 2010, 3). Within the community arts context, the purpose, definition and perceived ramifications of current program evaluation trends, remains highly contested (Goldbard 2015; Belfiore and Bennett 2010). Prevalent in the discourse are philosophical disputes about the notion of cultural value (that is, how the value and impact of community arts should be conceptualised, defined and measured) as well as technical disputes over the tools, standards and methodologies for effective and reliable evaluation practice (MacDowall et al. 2015). Trepidation of evaluation is also evident in the field (Barkley 2016; Belfiore 2014; Goldbard 2008).17 Compounding such issues for the Nuclear Futures cohort, of how to effectively understand and assess cultural and arts impact, were the complexities and spectres of deep nuclear time.

In response, led by host production company Alphaville, the Nuclear Futures cohort sought to create a tailored approach for evaluative practice to satisfy the culturally-diverse needs and perspectives of the partnership and draw on the strengths of the creative practice -- and to produce relevant, usable, credible, and valid findings.18 The 'READ' model was conceived in 2012 during the program development phase of Nuclear Futures, and was advanced as part of research undertaken at Queensland University of Technology in 2013-15 in cooperation with Alphaville and Nuclear Futures partners.19 The model integrates the strategies of Reflection, Evaluation, Analysis and Documentation (READ) to create a wide lens for representing, interpreting, understanding, and evaluating the implications of the community arts activities/artworks; as well as systems for promoting shared learning, exchange, and creative development. Of high relevance, were the documentary art-making methods central to the collaboration, prominent across the majority of Nuclear Futures projects, that utilised creative research, photography, video, digital media and written publications. To achieve a robust evaluative framework, these creative documentation methods were coupled with conventional evaluation instruments and organisational learning processes, as well as critical analysis generated via academic research. In addition, the cohort considered whether the outputs generated could be created and shared in such a way so as to extend partnership learning and legacy outcomes-- and how this may dovetail with the arts practice. During the Nuclear Futures trial and development of the approach, the READ model was implemented as follows.

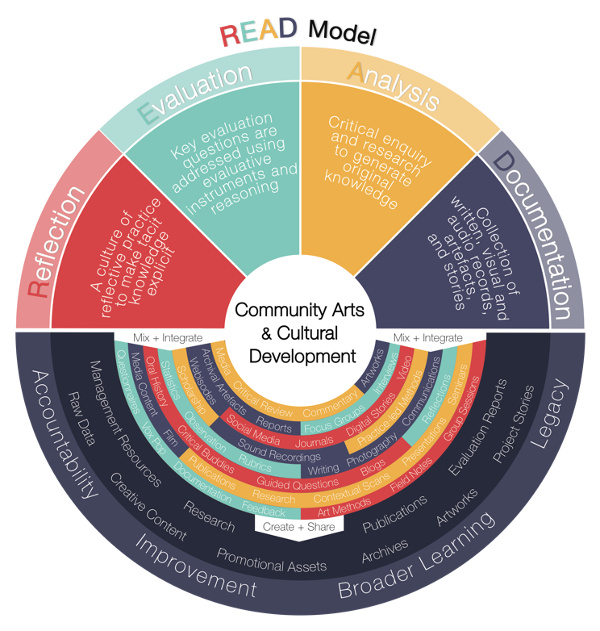

First, community members and artists were invited to reflect on projects and practice through journaling, shared reflection, interviews and other personal records to establish a culture of reflective practice. Reflective practice utilises individual and/or collective reflection in order to make explicit practitioner and participant knowledge generated through the arts practice (Schon 1983). Second, a set of key evaluation questions were determined (representative of partner priorities) and addressed using a strategic mix of evaluation instruments and methods (such as questionnaires, interviews, focus groups, assessment rubrics, etc). The findings generated by this more conventional evaluative strategy aimed to produce defensible and valid findings in line with partner needs (such as requisite data collection, reporting, and assessment related to accountability) using credible processes. Third, alongside the multiple arts practices was a program of scholarship, analysis and academic research to generate broader learning and dissemination of original knowledge, driven by a community of researchers, and focused on the wider implications arising from community arts. Fourth, thorough documentation of the program's delivery was guided by the creative, program, and legacy goals set at the site of practice for community story-telling and art-making -- where filmmakers, multi-media artists, and participants produced multi-platform 'products' using photography, video and film, audio recording, writing, infographics, oral history, community archiving, and public collection development. Captured were both the happenings of the program, and the ripples of impact arising from activities. (See Figure 1 a visual graphic of the READ model).

FIGURE 1: The READ model (Source: Barkley 2016, 173)

Supporting the four inter-linked strategies was a process of participatory integration and synthesis of the data collected involving a mix of stakeholders -- and a priority on information sharing to maximise real-time impact. Over the three years, the READ methodology produced and disseminated a diverse and valuable portfolio of raw, formative, and summative evaluative outputs including developmental findings, history-related resources, creative content/ artwork, management data, formal evaluation reports, partner insights, academic research, published materials, and media resources. Where appropriate and possible, resources and findings were shared in the public domain to extend the storytelling capacity of the community arts. Overall, the implementation of the READ model created immediate and longer-term benefits for the program, host organisation, and a significant number of stakeholders within the partnership (Barkley 2016).

Lessons for extending legacy impact

From the awakening intention to make the story go far, to meeting the pragmatic demands of program evaluation for the complex creative partnership initiative, the READ model evolved to support wide-ranging evaluative action (utilising a mix of qualitative, quantitative and performative methods), and demonstrated original and effective strategies for promoting learning and legacy impact.20 In pursuing an understanding of how evaluative processes might play a role in enhancing program impact, three strategies contributing to the program's legacy goal ('to make the story go far') became apparent. These strategies were: the generation and sharing of creative documentation; broader analysis by a community of practice and to 'unlock the academies'; and dissemination of content via strategic partner organisations for long-term storage and public access (Barkley 2016).21

For the creative documentation, the Nuclear Futures approach drew on the strengths of the creative practice, generated extensive new content and data, and offered an interpretive lens for analysis via creative processes such as curation, production, editing and archiving. By utilising documentary art methods to capture the processes and experience of participants, and represent the artworks created, a secondary round of creative material and storytelling was produced and disseminated (in addition to the original creative works produced). This provided new and varied opportunities for engagement and promotion of the community arts practice and subject matter during Nuclear Futures. More generally, and as explained in the literature, the documentation of processes and artefacts can enable a story to be taken further afield, and to be moved and used beyond the story's place of origin and context (UNESCO and ICCROM 2015). This was true for several projects within the Nuclear Futures initiative, where the message and impact of the community arts practice was enhanced and audience reach increased (both geographically and temporally) from the documentation processes.

One notable program example was the impact generated from the deliberate internationalisation of the Yalata Sculptures Project, involving the first Australian sculpture contribution to Nagasaki Peace Park in Japan, which was supported by a concurrent documentation project with professional and community artists.22 The documentation and mentoring process covered the sculpture-making, permanent installation, and official gifting in Japan, and resulted in skills development, capacity building, and transformative impact for participants. In addition, an extensive collection of original creative content was generated (which was highly valued by community participants and artists) and this provided a foundation for storytelling about the atomic art and communities involved that would not otherwise have been accomplished. Further, the documentation proved valuable for: securing international media coverage; public promotions, including making promotional videos used for crowdfunding, partner publicity, and a Nuclear Futures showreel; producing new creative works, such as a short 10-minute documentary film (see 'Tree of Life' in this collection) and photomedia collection; and spin off projects into the future, including the prospective plan for a feature-length documentary film.

The second legacy-making strategy showing promise involved collective social enquiry to promote broader learning -- via collaboration between creative artists and researchers for community arts and cultural development. The strategy was based on the intent of 'unlocking the academies', and Alphaville was well placed to explore how the community arts practice might utilise the academies given a large number of individuals connected with the initiative had academic roles, interests, or previous research experience.23 From the commencement of the program a community of practice was initiated to augment partnership development and produce quality research outputs focused on the wider social, political and artistic implications of the initiative as it progressed.24 The Nuclear Futures community of practice "evolved around the common interest in the domain of 'art and the bomb', created with the goal of making explicit the knowledge generated through creative practice, and publishing original knowledge as research" (Barkley 2016, 127).25 The social analysis generated via this strategy has extended beyond the three-year timeframe of the initiative, and encompasses knowledge sharing in scholarly and industry domains via publications, conference papers, and presentations at seminars/ industry forums.26

Building on the above-mentioned methods, the third area of innovation was the wide-reaching dissemination strategy employed for distributing and positioning the creative and evaluative research, documentation, artworks, and publications in the community and public domains, to ensure the material remained accessible beyond the life of the program. For the partnering communities, large volumes of documentation and research (such as photos, videos, transcripts, publications and so on) were gifted back to participants and have become valuable resources of short and long term relevance. The material produced a record of community stories (in several cases previously unrecorded) and has supplemented personal/community archives. In one instance, the content has been utilised as communication resources for networking and advocacy work on the broader atomic-related and peace campaigns; and in another, has been used for community-related funding applications for spin-off projects.

In addition to dissemination through communities, partners, and Nuclear Futures networks, READ materials were distributed in the public domain to create long-term artefacts that are accessible in the future for use by researchers, artists and community members. A prime example is the strategic partnership forged with the State Library of South Australia (SLSA), which resulted in mentoring, training, equipment access, collection development, and enhanced storage and management of archival resources. Throughout the initiative, SLSA staff provided expertise and guidance to community members, artists and arts workers in the archiving of nuclear veteran and atomic art related materials unearthed during creative research. In response to the significance of the material generated, the Library initiated a new collection on South Australia's atomic history (as surprisingly, no collection existed previously), so that archival materials could be donated to the cultural institution for long-term management and storage.27 To date, several nuclear veteran families have contributed to the collection (which include oral history recordings, historical records, rare documentation, and personal artefacts) and continued partnerships with families have been established to support future donations. The SLSA collection will also house selected creative works produced via Nuclear Futures and content representing the experiences of South Australia's Yalata Anangu Aboriginal community.

Conclusion

As well as engaging contemporary audiences in the atomic messaging through the creative arts, the Nuclear Futures Partnership Initiative explored a question that has engaged (and eluded) governments, philosophers and artists alike since the beginning of the atomic age: What artworks and artefacts can endure across the deep-time of the nuclear future, and by what processes--if at all--is this achieved? The enquiry was ambitious, and reflected the program's intent 'to make the story go far' - to expose the obscured legacies of Australia's atomic history and extend the wider impact of the community arts and cultural development work being undertaken with partnering atomic survivor communities. While the dilemma of deep-time communication remains a spectre of the atomic age, well beyond the scope of a three-year community arts program, exploring legacy goals through the community arts practice (of which evaluation became an integrated component) afforded new insight into cultural and arts impact.

The process of embracing futures thinking, even modestly, during Nuclear Futures resulted in program outcomes and impact that would not otherwise have been achieved. Through the enquiry, the creative team considered questions such as: How can art be created to support community cultural development, audience engagement, original research, partnership development, and community archiving?; What multi-media outputs and broader range documentation of the art-making and artworks might enhance program impact?; Which dissemination platforms/ strategies/ partners would ensure value and information sharing, raise public awareness, and enable content to remain accessible, relevant and engaging for future generations? Linked to this, and in response to the immediate evaluation needs of the multi-partnership initiative, the cohort devised and experimented with an original methodology for exploring cultural and arts impact.

In re-imagining how community arts impact is envisaged, the Nuclear Futures cohort embarked on collective evaluative practice for the purpose of accountability, continuous improvement, broader learning, and legacy-making (Barkley 2016). Resulting were real-time innovations for the arts practice and program evaluation via the development and testing of the READ model integrating Reflection, Evaluation, Analysis and Documentation. The READ approach harnessed the strengths of the Nuclear Futures partnerships and documentary-inspired arts practice, and created then disseminated multi-platform artworks and artefacts reflecting the register of voices from the initiative. Further, the incorporation of legacy purpose into the community arts evaluation practice was an original and socially driven outcome of the READ methodology (Barkley 2016).

Discussed in the essay, are three of the strategies that contributed towards the legacy goal of building and enhancing program impact: multi-media creative documentation; collaborative research for 'unlocking the academies'; and community archiving and dissemination via inter-sectoral partnerships to support future data storage, management and access. The methods implemented via the READ approach generated diverse learning and appraisal outcomes, and an extensive array of evaluative and non-evaluative outputs including creative works and multi-platform documentation (secondary to the original suite of artwork) designed and positioned to prompt wide coverage and engagement in the atomic legacy testimonies, creative works, and on nuclear issues more generally. Through processes such as film-making, academic and industry publication/ dissemination, archival collection development, and the permanent installation of artwork at renowned cultural sites, the program's audience reach was significantly increased beyond the geographic and temporal constraints of the three-year, Australian-based community arts program. The READ approach generated myriad resources that were of immediate benefit for the program's community partners for ongoing campaigning, advocacy, storytelling, reporting, and partnership development; and longer-term public benefits from the donation of nationally significant material to cultural institutions that have taken on the responsibility for storing, managing, and keeping accessible material beyond the program's administration.

The inclusion of longer-term goals into the Nuclear Futures arts and evaluation practice (via the READ approach) raises new possibilities for community arts and cultural development practitioners interested in arts impact and legacy-making. Combined, the artworks and artefacts became the means by which the stories were, and will continue to be, circulated to wider audiences and communities in Australia and overseas -- intended as both message stick and invitation for researchers, audiences and communities to continue to learn and respond to Australia's atomic history. While it is too early to verify the extent to which the READ model was effective for achieving sustained results for making the story go far, the Nuclear Futures application does demonstrate that the READ model supported both the generation, and evaluation, of cultural and arts impact. In doing so, the newly developed READ model offers a robust and integrated framework for learning about and appraising impact beyond the atomic and community arts contexts, of prospective interest for evaluation, organisational learning, and program management in other fields including the Creative Industries, Education and Sustainability.

Works Cited

Alphaville. 2015. Nuclear Futures: Exposing the legacies of the atomic age through creative arts. Website. Retrieved February 13, 2015.

Australasian Evaluation Society (AES). 2010. Guidelines for the Ethical Conduct of Evaluations. Booklet. Retrieved May 20, 2013.

Australia Council for Arts. 2011. Community Partnerships sector plan 2010-2012 for community arts and cultural development (revised version May 2011). Web Retrieved May 15, 2013 (no longer available). See alternative link

Barkley, Ellise. 2016. An integrated approach to evaluation: A participatory model for reflection, evaluation, analysis and documentation (the 'READ' model) in community arts. Professional Doctorate thesis, Queensland University of Technology. Web. Retrieved December 10, 2016.

Belfiore, Eleonora. 2014. 'Impact', 'value' and 'bad economics': Making sense of the problem of value in the arts and humanities. Arts and Humanities in Higher Education, 14(1), 95--110.

Belfiore, Eleonora. and Oliver Bennett. 2010. Beyond the Toolkit Approach: Arts Impact Evaluation Research and the realities of Cultural Policy‐making. Journal for Cultural Research 14, 2 (2010), 121‐142 from http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14797580903481280.

Bell, Wendell. 1997. Foundations of Futures Studies: Volume 1 History, Purposes and Knowledge. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers.

--. 2002. 'What do we mean by Future Studies?'. In R. A. Slaughter (ed.), New thinking for a New Millennium: The knowledge base of futures studies, pp.3-25. London: Routledge.

Berndt, Ronald M., and Catherine H. Berndt. 1996. The World of the First Australians. Aboriginal Traditional Life: Past and Present. Canberra: Aboriginal Studies Press.

Boylan, Jessie. 2015. Atomic amnesia: photographs and nuclear memory. Global Change, Peace and Security, 28(1), 55-73.

Brown, Paul, Avon Hudson, Ellise Barkley, James Arvanitakis. 2013. "Arts and the deep nuclear future: a prospectus". in David Curtis and Lucia Aguilar (eds.) Linking Art and the Environment: proceedings of the first EcoArts Australia Conference, 12-13 May 2013, Wollongong NSW. Arts and Ecology Conference, Wollongong 12-13 May 2013. University of Wollongong.

Cox, Andrew. 2005. What are communities of practice? A comparative review of four seminal works. Journal of Information Science, 31(6), 527--540.

Cruikshank, Julie. 2007. Do Glaciers Listen? Local Knowledge, Colonial Encounters and Social Imagination. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

Curthoys, Ann. 1991. Unlocking the Academies: Responses and Strategies [online]. Meanjin, 50(2/3), Winter-Spring 1991: 386-393. Web Retrieved December 4, 2015, from

Gaiman, Neil. 2015. How Stories Last. [Podcast for the 'Seminars about Long-term Thinking' series]. The Long Now Foundation, recorded June 9, 2015. Available at: http://longnow.org/seminars/02015/jun/09/how-stories-last/

Galison Peter and Rob Moss. 2015. Containment. Documentary film on the prospects of managing nuclear waste. Producers Peter Galison and Robert Moss.

Goldbard, Arlene. 2008. The Metrics Syndrome [Online article]. PDF Retrieved May 23, 2013.

--. 2015. The Metrics Syndrome: Cultural Scientism and Its Discontents. In L.MacDowall, M.Badham, E.Blomkamp, and K.Dunphy (eds.). Making Culture Count: The Politics of Cultural Measurement (pp.214-227). London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Henige, David. 2009. "Impossible to Disprove Yet Impossible to Believe: The Unforgiving Epistemology of Deep-time Oral Tradition." History in Africa 36: 127--234. doi: 10.1353/hia.2010.0014

Hildreth, Paul and Chris Kimble. 2004. Knowledge Networks: Innovation through Communities of Practice. London: Hershey, Idea Group Inc.

Jacobs, Robert. 2010. Filling the hole in the nuclear future: art and popular culture respond to the bomb. Lexington Books.

Jolivette, Catherine, ed. 2014. British Art in the Nuclear Age. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd..

Keating, Clare. 2002. Evaluating Community Arts and Community Well-Being: An Evaluation Guide for Community Arts Practitioners. (eds.), Arts Victoria and Effective Change. Web Retrieved May 5, 2013.

Komizo, Yasuyoshi. 2013. Communicating the Message of Hiroshima to the World and Future Generations [Chairperson's message on Hiroshima Peace Culture Foundation website]. This article originally appeared in the column "Hiroshima no kaze" (Winds of Hiroshima) in the Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum mail magazine No.120 (issued July 1, 2013). Available at: http://www.pcf.city.hiroshima.jp/hpcf/english/about/chairpersonsE/article002.html

Lave, Jean and Etienne Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Long Now Foundation. 2015. 'The 10,000 Year Clock'. Web. Retrieved 5 May, 2015.

MacDowall, Lachlan, Martin Mulligan, Frank Panucci and Marnie Badham. 2013. Spectres of Evaluation [Unpublished workshop paper]. Centre for Cultural Partnerships, University of Melbourne.

MacDowall, Lachlan., Marnie Badham, Emma Blomkamp, and Kim Dunphy, eds. 2015. Making Culture Count: The Politics of Cultural Measurement. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Masco Joseph. 2006. The Nuclear Borderlands: the Manhattan Project in Post-Cold War New Mexico, Princeton, Princeton University Press.

Mittman, J.D, ed. 2016. Black Mist Burnt Country: Testing the bomb -- Maralinga and Australian art. ISBN 9780992335724

National Ideas Summit and Australia Council. 1990. Unlocking the academies: discussion paper and proposals for action from forum I following the National Ideas Summit (1990: Canberra). Redfern: Australia Council.

Nunn, P. and N.J.Reid. 2016. 'Aboriginal Memories of Inundation of the Australian Coast Dating from More than 7000 Years Ago', Australian Geographer, 47:1, 11-47, DOI: 10.1080/00049182.2015.1077539

O'Brian, John and Jeremy Borsos. 2011. Atomic Postcards: Radioactive Messages from the Cold War. Intellect Books.

Owsley, Douglas W., and Richard L. Jantz. 2001. 'Archaeological Politics and Public Interest in Paleoamerican Studies: Lessons from Gordon Creek Woman and Kennewick Man.' American Antiquity 66: 565--575. doi: 10.2307/2694173

Pearl, Amy. 2016. HTF 017: Reflecting on a Nuclear Legacy Podcast. Produced for Hatch Innovation and published on August 15, 2016.

Mars, Roman. 2014. "Episode 114: Ten Thousand Years". Retrieved 2 August 2016.

Rose, David. 2013. "Phylogenesis of the Dreamtime." Linguistics and the Human Sciences 8: 335--359. doi: 10.1558/lhs.v8i3.335

Schon, Donald. A. 1983. The Crisis of Confidence in Professional Knowledge. In D. A. Schon (ed.), The reflective practitioner: how professionals think in action (pp.3-20). New York: Basic Books.

Scriven, Michael. 2012. Conceptual Revolutions About Evaluation; Past and Future. Recorded lecture from The Evaluation Centre (Evaluation Café: September 11th, 2012). Video. Retrieved June 4, 2014.

Sebeok, Thomas Albert. 1984. Communication Measures to Bridge Ten Millennia. Columbus, Ohio: Battelle Memorial Institute, Office of Nuclear Waste Isolation.

Shetler, Jan Bender. 2007. Imagining Serengeti: A History of Landscape Memory in Tanzania from Earliest Times to the Present. Athens: Ohio University Press.

Slaughter, Richard A., ed. 2002. New thinking for a New Millennium: The knowledge base of futures studies. Routledge.

SNL (Sandia National Laboratories). 1992. Expert judgment on markers to deter inadvertent human intrusion into the waste isolation pilot plant [Tech. Rep. No. SAND92-1382 / UC-721]. Livermore, CA: Sandia National Laboratories

UNESCO and ICCROM. 2015. 'Why Document'. Re-org [website]. Web. Retrieved December 7, 2015. Wenger, Etienne., Richard McDermott and William Snyder. 2002. *Cultivating Communities of Practice (Hardcover), Boston: Harvard Business Press.

World Nuclear Organisation. 2013. Web Retrieved April 29, 2013.

Footnotes

- The term 'cultural amnesia' is used in the nuclear arts context to refer to the continued and wide-spread public ignorance of nuclear history and impacts, either because historical information has been obscured or omitted from the public record, or because information that was once considered important has now fallen into desuetude, inadvertently or because it represented a negative aspect of the past that has over time been ignored (based on general topic discussion at http://english.stackexchange.com/questions/205440/cultural-amnesia-what-does-it-mean). For the Nuclear Futures program, and for several key individual artists within the cohort, the impulse to make art as a means to counter the cultural amnesia associated with nuclear weapons testing and use was stated as a key motivation for the arts practice. For examples, see www.nuclearfutures.org, and the work of Australian photographer Jessie Boylan (Boylan 2015; http://jessieboylan.com) and Japanese multi-media artist Yukiyo Kawano (see Pearl 2016; http://yukiyokawano.com/about/). ↩

- The field of community arts encompasses the wide range of arts-based collaborative practices run by, or with, communities in partnership with professional artists and arts workers (Australia Council for the Arts 2011), and is the primary context of the research presented in this essay. ↩

- The Nuclear Futures program was hosted by Sydney-based arts company Alphaville, with principal funding from the Australia Council for the Arts, and the financial and in-kind support of multiple arts and non-arts organisations/ partners. ↩

- Sourced from Nuclear Futures documentation, courtesy of Alphaville. ↩

- This question gained collective interest during the creative practice, however was not a stated funding objective or deliverable of the program. While the question defies the scope of a three-year arts program, Six to seven decadesixty and seventy years on, eoners and scholars is luding traditional knowledge being pasleading projects in the enquiry catalysed the exploration of significant legacy themes and considerations (related to atomic art-making and the deep-future impacts of nuclear weapons testing and use) that enriched the community arts and cultural development processes undertaken. ↩

- The essay draws on research conducted at the Queensland University of Technology (QUT) during 2013-5 (Barkley 2016) and practitioner-insights from the Alphaville and Nuclear Futures creative team. During the Nuclear Futures initiative, the author played dual, yet distinct, roles that have informed the findings: first, as Program Manager; and second, as lead evaluator via the QUT research. (Full QUT findings available for download at http://eprints.qut.edu.au/97728/.) ↩

- Australian atomic art encompasses Aboriginal artwork and stories, as well as non-Aboriginal and internationally-framed work across creative mediums and genres. Examples of atomic art in Australia include theatre play Ngapartji Ngapartji (Big hART, see www.ngapartji.org)); Maralinga Sculpture by Lin Onus (Art Gallery of Western Australia); and the national touring exhibition of Australian atomic artworks, Black Mist Burnt Country (see www.blackmistburntcountry.com.au)). Of notable significance is the more recent increase in representation and recognition of Aboriginal community voices and experience in Australian nuclear art and storytelling. Available atUSA government research (Eds) Australian Art in the Nuclear Age, Unlikely, that history have been for future,st ↩

- The term 'register of voices' became terminology within Alphaville for the representation of atomic survivor perspectives and stories collated into the Nuclear Futures art-making, archive and documentation sourced from participants, interviews, images, creative works, documents, and press material. ↩

- Evidenced via the evaluation data collected and analysed by Alphaville and partners. More information and evaluation findings are available at www.nuclearfutures.org. ↩

- Futures Studies is one of several disciplines investigating future nuclear heritage, others include Moral Philosophy and Environmental Management/Sustainability. ↩

- Related, when deciding on a name for the Nuclear Futures program, 'Nuclear Futures' was selected as an acknowledgement that our future/s is inescapably nuclear (a result of past activities and existing atomic legacies). At the same time, the title also posed the question 'which nuclear future do we want?', given present and future policies, actions, warfare and experimentation threaten/promise different types nuclear future scenarios. ↩

- The research focused on the study of Aboriginal storytelling recall related to the effects of postglacial sea-level rise at different sites around Australia (Nunn and Reid 2015). The research suggests that continuous oral transmission of stories accurately recounting historic coastal inundation events may extend back more than 7,000 years-- a timeframe previously deemed improbable (Nunn and Reid 2015). In Western culture, the prospect that cultural continuity of orally transmitted knowledge and memories might be possible across time-depths of thousands of years has been generally regarded with skepticism, and the issue of how far back in time orally transmitted human memories can reach remains contentious (Henige 2009; Shetler 2007; Cruikshank 2007; Owsley and Jantz 2001). ↩

- Aboriginal oral traditions ('stories'), can also be conveyed in various ways, as narratives, testimonies, and as myths (Berndt and Berndt 1996). As well as 'stories', methods of traditional knowledge transmission include songs, dances and the 'law' of particular Aboriginal groups (Nunn and Reid 2015). ↩

- For second and third generation community members, this may involve learning and/or re-learning the the often oppressed stories from their own nuclear past, and reconciling this history with the current aspirations and capacity of the community. ↩

- Hibakusha is a Japanese term referring to the atomic survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings. ↩

- For Nuclear Futures, conducting a formal, and rigorous, program evaluation process was not optional- it was a contractual obligation of at least three of the funding bodies, and represented a potentially significant investment of resources based on these stipulations. This reflects trends more broadly in the field of community arts, where evaluation is a requisite aspect of arts practice and management (MacDowall, Badham, Blomkamp and Dunphy 2015). ↩

- At the Nuclear Futures site of practice, for example, during the scoping research trepidation of evaluation was recorded as an issue for numerous stakeholders at the beginning of the program (Barkley 2016). ↩

- The definition of 'evaluation' adopted by the cohort (based on stakeholder needs analysis and negotiated with the primary funder) was much broader than many conventional definitions, and extended beyond merit attribution. ↩

- The READ concept was collaboratively devised and implemented by Alphaville's creative team with input from several partners, and in particular through developmental work by Paul Brown as Creative Producer and Ellise Barkley as Program Manager. The QUT research involving the co-design, theorisation, scaling, and testing of the READ model was conducted by Ellise Barkley as lead evaluator, via the Doctor of Creative Industries (a postgraduate research program for industry practitioners). ↩

- It is important to note that many outcomes and original insights were achieved via the co-design of the READ model that are of relevance to practitioners engaged in program and arts evaluation, and that the application produced credible evaluation findings, shared learning, and catalysed strong engagement in evaluation amongst partners (Barkley 2016). This essay is focused on the domain of legacy-promotion, of relevance to community arts and evaluation practitioners interested in extending impact via diversified learning and evaluative processes. Analysis of the READ model as an evaluation methodology and its effectiveness is beyond the scope of this essay. ↩

- Please note, for this essay, it is not possible to verify and evaluate the extent to which these prospective legacy-making strategies may be effective (that is, to trace, measure and demonstrate their impact beyond the program's evaluation period) due to the time and resourcing parameters of the initiative. Rather, the strategies are presented and discussed speculatively, based on early insights and research into the READ approach at the Nuclear Futures site of practice across a four-year period of application (extending before and after the program duration) (see Barkley 2016). ↩

- On April 18, 2016, the first Australian sculpture was officially gifted to the people of Nagasaki, joining the internationally renowned collection of artworks from around the world at the Nagasaki Peace Park. Facilitated via the Nuclear Futures program, the Australian sculpture-gift originated from the remote Aboriginal community of Yalata, South Australia, and was gifted in collaboration with City of Fremantle, as lead city of Mayors for Peace Australia, and Cities of Cockburn and Subiaco in Western Australia. See www.nuclearfutures.org for further details on the project. ↩

- This notion originated in the early 1990s following the release of an Australia Council for the Arts discussion paper entitled Unlocking the Academies (National Ideas Summit and Australia Council 1990). The paper called for the problematic cultural and professional gaps between academics, journalists and media publishers to be addressed, as it was argued that too often academic knowledge is not accessible for the wider public or non-specialist audiences due to a lack of a common language, preventing knowledge exchange and learning between industry practitioner-researchers and academics (Curthoys 1991; National Ideas Summit and Australia Council, 1990). ↩

- In the literature, the approaches to, and benefits of, communities of practice have been enunciated by several analysts (Cox 2005; Hildreth and Kimble 2004; Wenger, McDermott, and Snyder 2002; Lave and Wenger 1991). ↩

- Scholarship so far has related to: Memory and narrative; Arts-Science interactions; The history of military and civil nuclear programs; Imperialism, the Cold War, and other key historical dimensions; Wastes and contaminated sites; Health and radiation impacts; The role of the arts (and specifically of community arts); Art, protest, and disruption; Justice and the arts; Resilience and survival; Eco-criticism; and Future Studies. ↩

- This Unlikely journal edition is one specific example of this type of research output/dissemination. ↩

- The collection is publicly accessible at the State Library of South Australia in Adelaide, and consists of a mix of hardcopy and digital formats. Some items may be embargoed to protect personal information, and will be released at a later date. ↩