In/Visible

by MERILYN FAIRSKYE

- View Merilyn Fairskye's Biography

Merilyn Fairskye is a Sydney-based artist and Honorary Associate Professor at Sydney College of the Arts, University of Sydney.

In/Visible

by MERILYN FAIRSKYE

Introduction: Pathways

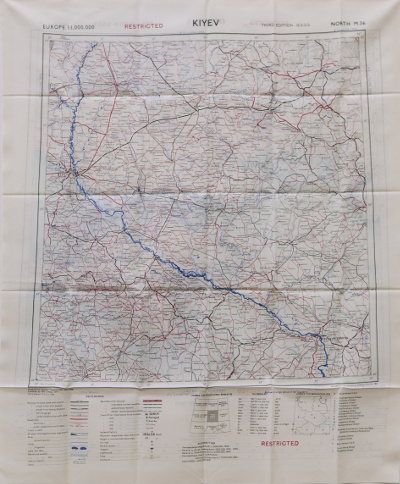

1) Silk map, Published by British War Office, London (3^rd^ edition, 1951)

In early 2009, preparing for a trip to Crimea, I bought a silk map off the Internet. On one side it showed a detailed map of Crimea, on the other, Kiev and surroundings. In the top left corner was the place name, Chernobyl. First published in 1947 by the British War Office, the map, which conveniently folds to fit inside a shirt pocket, had been issued to British military personnel engaged in covert actions in the Soviet Union during the post-war years. It traced interlocking networks of isolated factories, oil wells, mines and quarries, seaports, and lighthouses. A thick blue line ran diagonally from one corner to another--the Dnieper River, the main waterway through Ukraine.

Intrigued by the romance of the map, I followed the path of the Dnieper in inverse direction to the flow of contaminated water that ran through it from Chernobyl down to the Black Sea after the 1985 explosion. I stopped along the way in Yalta, where, in February 1945 Stalin, Churchill and Roosevelt met to determine the post-war reorganisation of Europe, making decisions that directly led to the Cold War, and to Sellafield becoming Britain's first nuclear complex in the late 1940s.

It is against this backdrop that my interest in visiting nuclear sites in order to make art developed, and which took me first to Chernobyl and most recently to Sellafield. I was completely unaware of the unsettling world I was about to enter.

Since then, I have visited The Polygon Nuclear Test Site in Kazakhstan, the Waste Isolation Pilot Plant in Carlsbad, New Mexico, USA, Dungeness Nuclear Power Station in the UK, along with other sites in the USA, Russia and Australia.

2) Dungeness Nuclear Power Station, Kent, U.K. (2014) 02_Dungeness

I have created videos, an artist's film Precarious and photo series that explore the relationship between technology, atomic landscapes and community, and the lived experience of what Joseph Masco has termed 'the uncanny nature of radiation' (Masco 2006, 28).

Long Life (1)

See also: Precarious, an artist's film (1hr 5min).

Surrounded by secrecy, located in remote environments, vulnerable to weather, flawed protocols, political priorities, mismanagement and corruption, nuclear sites are often beautiful, and always compromised. In this text I suggest that when visual artists go to these places to make work, something else happens beyond the documentary. This 'something else', the aesthetic construct, has the potential to transform the powerful events of real life and thus transform the viewer's experience of them.

Fieldwork

Another time, I was walking on the fells, have done for twenty years. And I was up on Great Gable with a group of people the day of Chernobyl. There was a terrific storm and we had to lie, actually lie on the ground, hailstones and rain and we were absolutely soaked. We got home and heard about this Chernobyl. Even fifty years, or is it forty year, whenever it was, there's still sheep there that's not allowed to, they're still on the ground. I supposed I must have got a bit that day. -- Joe Farrell, labourer, Sellafield (Interviewed in: Davies 2011, 28-29)

Looking across to the fells from Sellafield (2015).

I will briefly discuss my Chernobyl experience as a means of introducing my methodology for art making around nuclear sites. I will then discuss my recent visit to Sellafield, one of the deadliest sites in the world, and how, in Seascale, the small seaside village next door, the uncanny became manifest.

Before I could visit the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, I needed a visa from the Ministry of Ukraine for Emergencies and Affairs of Population Protection from the Consequences of Chernobyl Catastrophe1. Early on the designated day, a small car was waiting for me outside my hotel. An official guide was to meet me onsite. I would be the only visitor that day. The weather was bleak, shifting between sleet and heavy snowfall.

Driving into Chernobyl, past the security checkpoint, there was a long row of abandoned houses that stood on snow-covered ground still contaminated by radiation. Further along the road more toxic houses were shrouded in a thick layer of clay intended to contain the spread of contamination and prevent runoff into the earth. Nearby a herd of small Przewalski's horses grazed amongst a field of mounds and faded radiation signs. The harsh winter drained the colour out of everything. The grey, bleak landscapes were paradoxically, reassuring, and became the visual motif of the artworks I made. In Chernobyl, a heavy winter is good protection against radiation, because radioactive dust is trapped under the ice and snow.

I recorded video with a small, low-res camera handheld out the window of the car as it sped along. Later, in the edit suite, the moving footage was time-stretched to 100 minutes,2 to the point where the image was in danger of disintegrating. The images that resulted from the technical constraints of camera and software meshed with the metaphor of Chernobyl in what seemed to be an apt and poetic way.

The Monument to the Chernobyl Liquidators, Chernobyl, installed 1996. The inscription says "To Those Who Saved the World" (2010)

Fieldwork II was my first 'nuclear' artwork, and the trigger for a significant shift in the direction of my art practice, and in my thinking around anything 'nuclear'. The images I captured that day slipped between documentary and imaginary. Anchored to a particular place, but also loosened from it. One year later, I made a second visit to gather more material.

When I started to create work from Chernobyl, I had no idea what is it that an artist can represent in the aftermath of such a catastrophe. What relationship might exist between the event, its geography and architecture, and how I recorded it in order to make art? I also had to consider how, with something as concrete and dangerous as a nuclear accident, artworks might enter an imaginary rather than a didactic or documentary space as a way of evoking the complexity of this accident for people, the landscape and history.

The two visits shaped the approach I have followed at other sites. Each site has unique conditions around access, security and opportunity. It's not always possible to go back a second time, so I capture everything I can--as still and moving imagery, and sound. If possible, I scout a location first, set up the camera and wait for something to happen. I make 360 degree panning shots and shoot many hundreds of still images as well as video although I may not always know what the camera is seeing until afterwards. Everything that happens/appears has the potential to be useful.

I use contemporary voices and the stories of a range of people, keeping myself silent and invisible apart from my critical (and subjective) role in the construction of the work. People and place are prioritised over information, everyday experience over sensational events. My approach is more intuitive than methodical.

In the studio the subject is distilled from the mass of material accumulated from research and the visual/audio material captured in the field, a process that involves extensive looking, listening, building, assembling and disassembling.

In her essay about negotiating the Field of Mars reserve in northern Sydney, Vanessa Berry discusses the field as a metaphor of enclosure, as a "...cohesive force for the gathering of specific topographical and physical features, human and non-human presences, and events in the form of knowledge, memories and experiences" that whilst it can take a linear narrative form, such as a timeline, or a walk, it also allows for expanded and contingent narratives to be developed (Berry). This particularly resonates with my approach, although I undertake fieldwork primarily as a mode of enquiry and not as the artwork/experiment itself. Yet the work that results is informed by my process when I am on site, as well as by the raw material that results from me being there. 3

Stockholm Syndrome

You know the Americans denied us access because of the Taft Agreement to any material that would help us build the bomb. They wouldn't give us plutonium even though our scientists had done a lot for them. They wanted to be top dogs and still today want to be top dogs in everything and unfortunately we'd to go our sweet own way. Rutherford and all of them, you know, the atomic scientists, then Penny, they all came back to England and did their bit and we got the bomb...I left Sellafield on January the first 1990 as a free man but still plutonium exposed. Oh aye, it was a great job, don't get me wrong. -- Cyril McManus, ex-commando, foreman, union leader, Sellafield 1953-1990. (Davies 2011, 77)

Sellafield Nuclear Site, with the Irish Sea beyond (2015)

My most recent trip was to Sellafield in Cumbria, the site of Britain's first atomic installation, a toxic waste dump in some of the most contaminated buildings in Europe. Since 1947 materials for nuclear weapons have been produced there. Cumbria, a picturesque county in the northwest of England, is inscribed by paradox.

Bounded on one side by the Irish Sea, on the other by the Pennine Hills, much of its terrain comprises the renowned Lakes District National Park. Wind farms are scattered across the county, including Walney Wind Farm, one of the world's largest offshore wind farms, located 14 kilometres west of Barrow-in-Furness, a former shipbuilding town overshadowed by the huge BAE Systems Dock Hall where the Trident nuclear submarines are built. BAE Systems is the town's biggest employer.

Barrow-in-Furness will be my base for the week I spend in Cumbria. Jean McSorley, veteran anti-nuclear activist and writer, provides generous hospitality, extensive background information and introductions. Her account of Sellafield, Living in the Shadow, that I read before arriving, is a compelling introduction to the nuclear complex and the community around it prior to 1990 (McSorley 1990).

BAE Systems Dock Hall (2015)

I explore Barrow before I travel up to Sellafield. I can't help but notice that wherever I go there's the BAE Dock Hall, looming at the end of every street, overshadowing the town. Police stop me on two occasions when I take photographs of it from public roads, and my details are taken down. One of the police mentions a terrorist watch list.

The next day, sixty kilometres up the coast, I meet up with Martin Forwood, who is co-convenor of C.O.R.E. (Cumbrians Opposed to a Radioactive Environment) and a long-time local resident. Martin will take me around Sellafield, the accident-prone nuclear fuel reprocessing and decommissioning plant, formerly known as Windscale, my guide on an unofficial tour. Its two reactors, Pile 1 and Pile 2, were built to produce plutonium. A radiological poison processed from uranium, plutonium is used in nuclear weapons. When Britain exploded its first atomic bomb in 1952 in Australia, the plutonium came from Sellafield. The toxic site that is Sellafield today is just one of the legacies of Britain's atomic aspirations. Others can be found closer to home, at the Montebello Islands, Maralinga and Emu Field in Australia.4

Approaching Sellafield Nuclear Site (2015)

Sellafield was a WWII munitions factory set in sheep and dairy farm country before it became Britain's first nuclear complex in the late 1940s. People left the farms to work at the plant, which today directly employs almost one-third of the local work force, in a compound where radioactive waste lies in ponds and silos. Its exterior walls and fences are topped with razor wire. Since 1947, the British government has targeted regional economic and business interests around the nuclear industry, creating a community that depends on Sellafield for its survival. Sellafield no longer produces nuclear weapons or power and its activities today are primarily the decommissioning of historic plants, reprocessing facilities and waste stores, and reprocessing fuel from UK and international nuclear reactors. It costs British taxpayers £1.5b each year for the cleanup, with the total lifetime cost estimated to be £162 billion and rising over a projected 110 years. This will largely be paid for by future generations (Fairlie 2016).

The former Visitor's Centre (2015)

The corporate-looking former Visitor's Centre (with its own café and gift shop) has been closed since the late 2000s, and is now a conference centre. Sitting beside the well-guarded entrance to Sellafield it belies the ramshackle accumulation of aging, decrepit buildings and newer structures visible beyond. These structures sit dangerously close to each other on an overcrowded 2.5 sq. km site that contains over 1000 separate nuclear facilities, including many redundant buildings associated with the early defence work. The structures include breached concrete silos that leak highly radioactive waste into the soil, and decaying buildings at risk of explosion. Converted spent fuel and an unknown inventory of untreated legacy waste are stored in interim facilities onsite in increasingly dangerous conditions, awaiting a long-term off-site storage solution.

Low-level waste is currently sent by train to Drigg Low Level Waste Repository (Drigg LLWR) six kilometres down the coast, nestled between a tiny request stop railway station and the Irish Sea. I passed the plant on the train up from Barrow-in-Furness, it's surrounded by a dense fringe of trees just a few metres from the train line that conceal the interior from public view. Secured sidings take the trains transporting nuclear materials in metal containers into the dump to be sealed and then stored in concrete vaults. A few years ago, they were buried in trenches. Drigg, under threat from coastal flooding and erosion, is expected to reach capacity sometime in 2018.

Despite its beauty, the fields and fells around Sellafield and Drigg are part of a blighted landscape. No part of the environment is free of the invisible, persistent reach of radioactivity. A major fire broke out in one of the Sellafield reactors in 1957 that spread contamination across the countryside and Europe. There have been numerous accidents and spills since then. Helped by rain and high winds, a radioactive cloud blew in from Chernobyl to settle over the region in the days and weeks after April 26, 1986, and livestock and produce became heavily contaminated. It was only in 2012 that restrictions were finally lifted on Cumbrian sheep farms. More recently, in mid-2015, a site was approved for a new complex of nuclear power plants near Sellafield. There's no way back to a non-nuclear environment.

The local economy depends on Sellafield to keep it going. Jamie Reed, then sitting Labour Party MP, resigned in late 2016 to take up a high-profile management role with Sellafield Ltd., but not all locals are necessarily acquiescent. Many residents are increasingly uneasy about West Cumbria becoming a nuclear garbage bin. The Cumbria County Council, bowing to community pressure, recently ruled out a proposed area north of Sellafield as the site of a deep geological waste repository. That's 140 tons of plutonium and hundreds of tons of other high-level nuclear waste accumulated at Sellafield since 1950 which now has nowhere to go (Pearce 2015).

The history of British nuclear testing in Australia established a precedent of nuclear cooperation between a pliant Australian government and the UK that could, over 65 years later, still have persuasive weight. The recent South Australian Royal Commission into the Nuclear Fuel Cycle released its findings in late 2016 (NFCRC Final Report). It . Ithed its findings in 2016r the , and then, in as about to enter.has recommended a deep geological facility be built in South Australia to import the world's high-level nuclear waste. The toxic legacy of the British atomic enterprise, stored so precariously at Sellafield, could well end up in South Australia5, thus completing the cycle of nuclear colonisation that began before the UKs first atomic bomb was detonated in the lagoon between the Montebello Islands off the Western Australian coast on 3 October 1952. That atomic bomb, like the ones that followed at Maralinga and Emu Field, was made using plutonium produced at Sellafield from uranium oxide exported from Australia in early 1952.

Aerial view, Drigg Low Level Waste Repository. Photo: Google Earth (2008)

Slow Violence

By slow violence I mean a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all. (Nixon 2011, 6)

My tour with Martin Forwood is unofficial. Following September 11, 2001, public visits to onsite areas at Sellafield have been limited and official visitor permits are hard to get.6 Before we set off, Martin checks I've got my passport with me. He says I might need it. Approaching Sellafield, we stop by the roadside on a hill a couple of kilometres away from the plant in order to get an overview of the countryside. I set up my tripod. It's a picture postcard scene--expanses of lush green fields dotted with picturesque farmhouses, grazing sheep and cattle, the Irish Sea glistening in the distance--punctuated by the abstracted building block shapes of Sellafield that stretch across the frame of view. There is nothing spectacular or even vaguely alarming about this view of one of the most contaminated sites on earth, and nothing to suggest the radiation and nuclear waste that has suffused the surrounding landscape and community for over seven decades.

Sellafield country (2015)

Within a couple of minutes a police vehicle arrives from the Civil Nuclear Constabulary. Sellafield Ltd. takes security seriously and employs an armed police force as well as a private security force. The road we are on is quite deserted, at least a kilometre from the plant, so I am surprised anyone has observed us. After checking our passports, inspecting the camera and asking a few questions about our purpose in being there, the officer drives off.

Martin points out the various structures that make up Sellafield. Many of the older buildings we can see hold tons of legacy waste dating back to the 1940s and 50s, left behind by the teams working on the bomb, not because they intended to leave it for future generations to deal with, but because no one at the time thought of it as a problem. It is only in recent times that the focus has shifted to the question of environmental protection and how to empty these overcrowded, vulnerable facilities.

Sellafield, from the eastern boundary (2015)

We drive closer to the plant and park behind Sellafield Railway Station before walking past the buildings to the water. It's unnerving to be so close to the wire-topped fence that surrounds the plant knowing how much radioactive material is packed into the structures that jostle for space just metres away. To the casual passer-by, the view over the fence wouldn't mean a great deal--just a rather crowded industrial site. But one of the most hazardous buildings, known as B30, isn't that far away. Piles of old nuclear reactor parts and decaying fuel rods that aren't recorded on any inventory line the murky cooling pond in the centre of the building. At the bottom of the pool, pieces of contaminated metal have dissolved into an irradiated sludge. I've seen the leaked images obtained by anonymous photographers published in The Ecologist, 27 April 2014, and placed in the public domain a few days later that depict some of the decrepit legacy ponds including B30, seagulls bathing on the water, cracked tanks and derelict concrete buildings. 7

B30 pond, Sellafield, photographer unknown. Published in The Ecologist, 27 April 2014.

Shortly after, we reach the boundary fence near Sellafield's outlets to the Irish Sea when another Sellafield security vehicle pulls up. This time two armed police get out. They give us the third degree, check passports, inspect every item of camera gear, including what's in the 4WD, take down all the details, make a phone call, and then want to look at all of the photos on the camera card, to ensure no inappropriate building details have been captured. There's so much to click through, and the sun is shining directly on the camera's LED screen making it hard to see. I have to explain what each shot is. It's a lengthy process that annoys one police in particular. He's told me the alternative is to surrender my camera, so we persevere. This is the fourth time I've been stopped by police in two days in Cumbria whilst on public land. I'm starting to doubt the efficacy of my chronic "I've got nothing to hide" approach, It's unclear what the actual security problem is because there's a detailed, comprehensive aerial view of the site on Sellafield Ltd.'s website that reveals a lot more about the buildings and their location than any shots would from outside the perimeter.8 And you can find similarly detailed views on Google Earth, which, unlike the Google Earth images of Los Alamos, haven't been doctored. But it's made clear we can't stay where we are, so we head back to the car. There's still plenty more to see in the immediate neighbourhood.

Aerial view, Sellafield Nuclear Site. Photo: Sellafield Ltd. Date unknown.

We have lunch at the adjacent seaside village. Seascale (population almost 2000) is overshadowed by Sellafield down one end of the beach and Drigg waste dump just up the road. People walk their dogs on the sand but no one swims in the sea. In Victorian times Seascale was a popular holiday resort with dozens of boarding houses, but now it's an eerily quiet former company 'town' with a welcome sign that lists multiple beach safety items and another sign that warns about a weapons testing range on the beach. Neither mentions radioactivity. There's one café open with seating for four that closes at 4pm. We pay for the only items for sale apart from potato crisps--two Cornish pasties--and wash them down with a pot of tea.

Between 1939 and 1947 when Sellafield and Drigg were the sites of munitions factories, Seascale provided accommodation for the workers. After the British nuclear program commenced it became a dormitory community for Sellafield. In the 1950s it was known as 'the brainiest town in Britain' because of the number of research scientists living there (St Cuthbert's Church 1983, 2). Stories told about the life of Seascale's inhabitants in the 50s remind me of the privileged hothouse life in Los Alamos during the days of the Manhattan Project as depicted in the TV series "Manhattan". Today, it's a village in decline mostly visited for the golf course nestled next door to the nuclear plant. I'd first heard of Seascale several years before from international media reports after a local taxi driver went on a shooting spree in mid-2010, leaving 12 dead and another eleven injured. Then, later, I read accounts of radioactive liquids discharged to the Irish Sea that extensively contaminated the beach, leading to its closure and drawing ongoing complaints by the Irish and Norwegian governments as contaminated materials continued to wash up on their shores (Fairlie 2016).

Teeing off at Seascale Golf Course. Photographer unknown. Date unknown.

They just sort of discharged things up chimneys, dumped things where it suited them, and the effluent went out to the Irish Sea...The pipeline went out for three-quarters of a mile and the plutonium was supposed to adhere to the mud at the bottom of the sea in perpetuity, but of course it doesn't. It moves about. That was all right when they weren't using much, but they went on doing this until the MAFF9 people began to get a bit anxious and they had the Isle of Man grumbling. -- Marjorie Higham, nuclear chemist, Sellafield 1951-1965. (Davies 2011, 48-49)

Whilst these earlier procedures had given way to more stringent processes around discharges, in November 1983 a mixture of radioactive waste, solvent and water was deliberately discharged from Sellafield into the sea, caused by management errors (Hansard 1983). The national media coverage and public outrage that followed drove the plant to introduce a more rigorous beach monitoring program that soon led to the discovery of a lot of contaminated objects on the surrounding beaches that had been discharged through the pipelines. This reinforced the conviction held by many locals that family visits to the seaside were responsible for the cluster of childhood leukaemia and lymphoma cases in the village between 1955-1984. With no evidence to back the theory up, Sellafield management claimed the leukaemias were caused by a mysterious virus brought into the community via the huge influx of outside workers who joined the plant in between the 50s and 80s. Meanwhile a 2003 British Government study found plutonium in the teeth of all children across Britain that was linked to Sellafield (Barnett 2003).

Martin Forwood and Geiger counter at Newbiggen saltmarshes (2015)

Over lunch, we plan to go to the Drigg Low Level Waste Repository, and then on to the saltmarshes at Newbiggen where the layers of radionuclides in the mud will reveal a snapshot of Sellafield's waste discharge history over several decades and send Martin's Geiger counter into overdrive. It is a popular route for people walking their dogs, but there aren't any signs warning of the contamination. On our way out of Seascale, we drive past a row of houses on top of the ridge overlooking the sea. A pink house stands out amongst the more subdued cream and white ones. It's called 'Singing Surf'.

Birds

Singing Surf (2015)

Later, as dusk settles over the fells around the 17^th^ C stone farmhouse Martin shares with his partner and C.O.R.E. co-convenor Janine Allis-Smith, he recounts the story of Singing Surf's former occupants. Jane and Barrie Robinson, twin sisters, lived there for many years. A flock of several thousand pigeons congregated on the roof of the house every day. The sisters created an unofficial sanctuary for them, feeding them and tending to sick birds. The flock became so big that the local council decided to cull the pigeons to reduce the numbers. It came out that every night the birds were flying back to Sellafield where they would roost in dusty rafters in the buildings, including those housing open storage ponds dating back to the 50s and 60s. The council was alerted and after an investigation samples were taken. The levels of radioactivity in the breast meat were significant, as were high levels of plutonium found in the birds' feathers. This prompted the then Ministry of Agriculture to issue a public warning that people were not to come in contact with the birds or kill or eat them. The entire flock was then culled. The problem arose as to what to do with the radioactive carcasses, which couldn't be dumped in with the local rubbish collection since they were now classified as nuclear waste. Eventually they were placed in lead canisters and buried at Drigg. But if the pigeons were radioactive, then so too were their droppings. The top layer of garden soil at Singing Surf was dug up, and along with garden furniture, gnomes and other items, placed in lead canisters and buried at Drigg. Other avian visitors to Sellafield--migratory swallows, and sea gulls who like to swim on the ponds--were subsequently found to be radioactive, and a new level of nuclear waste entered the vernacular--flying waste. But that wasn't the end of Martin's story.

The second of June 2010 was the day that local taxi driver Derrick Bird embarked on a wild shooting spree. Twelve people were slaughtered and eleven people injured, three critically, over the course of the rampage. Sellafield went into lockdown. Bird had worked at Sellafield as a joiner until he lost his job in 1990 when he was convicted of stealing materials from the workplace. Now driving taxis, he blamed the plant and his more successful twin brother David for his cascading financial problems. David was his second victim, shot in his bed. Jane Robinson was his last, fatally shot as she delivered catalogues to houses in Seascale, just a few metres form her home.

Roadside tribute to Jane Robinson, Seascale, U.K. (2010). Photo: Clive Parkinson/Nick Shimmin.

In/Visible

Yet the punctum shows no preference for morality or good taste: the punctum can be ill-bred. -- Roland Barthes 1993.

The next day I take the train to Seascale and capture more audio-visual material. After being stopped twice the previous day I hesitate to get too close to Sellafield and instead wander along the water's edge and around the village with my camera. It's bleaker than the previous day and dark clouds gather overhead. Village life quietly unfolds around me, much as it must have done on that day in June five years before. The streets are semi-deserted. The café is closed. A few people walk their dogs on the beach; several golfers can be seen on the golf course that abuts the plant. Mindful of my host's admonition that morning not to make a nuisance of myself, I try to make myself invisible as I hover with my camera on Drigg Road in front of the pink house. I feel like a voyeur but don't want to leave. Eventually I move across the road, to a tiny allotment that leads down to the beach, and watch from there. A sign warns trespassers to beware of adders. Overall, it's an unsettling day.

Radiant, Media Wall, Bath Spa University, 2015.

A week later, in Bath, I create a Sellafield sequence to add to Radiant, a vertical video work that is then exhibited on the Media Wall at Bath Spa University. Taking landscape into the expanded portrait format, the installation places the viewer in a corporeal relationship to unfolding scenes of different nuclear landscapes in the UK, Australia and Kazakhstan. Each sequence is introduced with an historical image of the particular nuclear facility, annotated with the years of its actual or anticipated life span, followed by high-resolution still images placed in a dissolving timeline. The first sequence focuses on the Sellafield environment; the final sequence, captured the previous year in Dungeness, depicts falling sea birds, foreshadowing the story of the Seascale birds. The audio--a dial-in phone recording of alarm signals at Sellafield, wind rustling across the Kazakh plains, the low registering of a Geiger counter at Ranger Uranium Mine, and waves crashing against the shored-up shingle surrounding Dungeness Nuclear Power Plant--creates a spatial and temporal logic that works within and around the images. The launch of the work in Bath coincides with the controversial decision of the UK Government to enter into a partnership with the Chinese Government to build a new nuclear power plant at nearby Hinckley Point.

Radiant, Media Wall, Bath Spa University, 2015.

There is no overarching narrative in this work--instead, a flow of dissolving fragments that accumulates to build a sense of the precariousness of the atomic enterprise, and the vulnerability of the landscapes and the people who live with it and who inhabit its aftermath. Although there are vast archives available of images captured at these sites that I could easily draw on, I need to be present, in the place, encountering whatever it is that is there, in order to make something of it. But I can't say with certainty what this something is, or what is made visible. I'm drawn to the things that can't be pictured--atomic dreams and optimism gone awry, human fallibility and nuclear legacies, the ineffable relationship between people and place. And the deceptive, vulnerable beauty of many of the sites, often located in remote environments and surrounded by secrecy. The visual drivers are the sites themselves, what is to be found there and what they suggest. The emotional driver is the underlying pathos of the brevity of human life set against the incomprehensible longevity of radiation.

There's always Barthe's 'punctum' to bind me to a particular place--for Barthes it was the emotionally wounding, affective detail of a photograph that breaks through its ostensible subject to prick the viewer and lead to a different, more affective understanding of the image (Barthes 1993). Kristine Stiles discusses the difficulty for viewers in finding their own punctums in images with nuclear subjects, where invisible pathologies are embedded in the subjects indexed in the photographs, eluding the prick of the punctum which must then be imagined or conceptualized by the viewer. She argues that "the ability to visualize the ever-present haunting of the nuclear age is (itself) the punctum of nucelographic images" (Stiles 2016, 76-77). But if place precedes the photograph as the field of vision, the punctum can also come out of the (haunting) experience of 'being there'; when a particular encounter, incident or understanding breaks into perceived reality and completely reframes it--the punctum-in-place. As I discuss later, this can include the different experiences of the artist and the viewer of the art work. The punctum I experienced In Chernobyl came out of being left on my own in the playground in Pripyat, the empty heart of the Exclusion Zone. In the low winter light everything was still and flat. Surrounded by the thick silence of the heavy snow, I couldn't help but think, so this is what it's like, after the end of the world.

"Playground" from the Plant Life (Chernobyl) series, 2011.

At Sellafield, the punctum came down to the intertwined stories of the birds and the twins. A twin myself, I'm drawn to it again and again. Making creative sense of it is a work in progress.

Being There

Away from the drama of the spectacular nuclear accident with its "instant, sensational visibility" the nuclear age is not easily resolved as subject matter for contemporary art. How can we convert into image and narrative the disasters that are slow moving and long in the making, and that "remain outside our flickering attention spans" in such a way that they will be apprehended? (Nixon 2-13). Whilst musicians, games designers, photojournalists, filmmakers and artists have found powerful materials to engage with around catastrophes and apocalypse scenarios, nuclear legacies spread across time and space resist easy artistic representation. They can't be represented directly and exist in the artwork as affect, somewhere between image and viewer. Simple strategies are used to achieve this. The logic of sound and image is spatial and temporal rather than narrative. Didacticism and polemics are avoided. Titles and intertitles offer context and spare historical detail, providing a discursive anchor to the real. Scale and the individual work's physical placement in the viewing space are carefully considered. Tension between the seen and unseen is intentionally amplified to create a sense of unease and uncertainty that can lead the viewer to question what they are seeing and to put themselves in the picture.

Merilyn Fairskye. "Apartments", from the Plant Life (Chernobyl) series, 2011.

Faced with the visual absence of people, the viewer is the "absent figure expected to improvise its own narrative" (Dolk 2009) about human and environmental vulnerability. This absent figure must do the work, putting themselves in the picture to complete the work. This double 'work' might offer what Nixon terms "imaginative definition to the issues at stake" (Nixon 2011, 6).

This is an aesthetic approach that emphasises the act of creation and construction over a passive recording and reconstruction of the world. It is anchored to the subjective human experience of 'being there' for artist and viewer both. So what might the slash of the title In/Visible suggest in relation to this approach? For the artist, this experience occurs quite literally, in the visible place (of the initial fieldwork) where the invisible (something) lurks, and for the viewer, it occurs metaphorically. Taking Dolk's hypothesis on board, you could say that the (absent) viewer is present somewhere in between the 'framing' (conceptual and material making, and presentation) of the work and the experience of it, and indivisible from it. If there was a punctum for the viewer, it would lie in the capacity of the artwork to bring them into that in-between place where they can put themselves in the picture, into the time of it, and imaginatively "visualize the ever-present haunting of the nuclear age" (Stiles 2016, 76).

I now have a growing archive of nuclear material and from a bounty of still images, video footage, writing and research, new work emerges. If this work succeeds, it will be because it makes the (nuclear) world felt. And in doing so, perhaps it can disturb the way we think about this world.

PS

A blank white website provides disembodied narration in both Japanese and English. The website acts as a virtual anchor for an inaccessible exhibition that is itself an artwork. In 2014 Japanese artist collective Chim↑Pom initiated a series of twelve specifically-commissioned artist projects to be located inside three buildings in the radioactive zone surrounding the Fukushima Daiichi Power Plant. Don't Follow the Wind was launched on March 11, 2015, to mark the 4^th^ anniversary of the disaster. Participating artists include Chim↑Pom, Eva and Franco Mattes, Taryn Simon, Nobuaki Takekawa, Ai Wei Wei, Aiko Miyanaga, Grand Guignol Mirai, Nikolaus Hirsch and Jorge Otero-Pailos, Kota Takeuchi, Meiro Koizumi and Ahmet Öğüt. This exhibition will be accessible to the public only when the site is assessed to be radiologically safe for people to enter it, at some time in the future. For now, it is an apt metaphor for the in/visible. But being there is a long way off.10

All photographs are by the author unless otherwise specified.

Works Cited

Barnett, Anthony. 2003. Plutonium from Sellafield in all children's teeth. The Guardian, 30 November. Web, accessed February, 2017.

Barthes, Roland. 1993. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, translated by Richard Howard. London: Vintage.

Berry, Vanessa, "Field of Mars: Remains of the Commons". Unlikely, Issue 02, undated. Web.

Carpenter, Ele. 2016. The Nuclear Culture Source Book, London: Black Dog Publishing.

Davies, Hunter ed.. 2011. Sellafield Stories-Life with Britain's First Nuclear Plant, London: Constable.

Dolk, Michiel. 2009. Merilyn Fairskye 100 artist catalogue. Sydney: Stills Gallery.

Fairlie, Ian. 2016. "Sellafield exposed: the nonsense of nuclear fuel reprocessing", The Ecologist, 6 September 2016, Web. Accessed December 2016.

Fairskye, Merilyn. Fieldwork II, Web.

Fairskye, Merilyn. "Playground" from the Plant Life (Chernobyl) series. Pigment print, 80 x 218cm, 2011.

Fairskye, Merilyn. "Apartments" from the Plant Life (Chernobyl) series. Pigment print, 80 x 120cm, 2011.

Hansard. 1983. UK Parliament, 21 December 1983. Web. Accessed March 2018.

McSorley, Jean. 1990. Living in the Shadow: The Story of the People of Sellafield, , London: Pan Books.

Masco, Joseph. 2008. The Nuclear Borderlands: The Manhattan Project in Post-Cold War New Mexico. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Ministry of Internal Affairs Ukraine: Web. Accessed March 2018.

New Scientist,Web. Accessed December 2016.

NFCRC Final Report: Web. Accessed December 2016.

Nixon, Rob. 2011. Slow Violence And The Environmentalism Of The Poor, London: Harvard University Press.

Pearce, Fred. 2015. "Shocking state of world's riskiest nuclear waste site", New Scientist, 21 January. Web. Accessed December 2016.

St. Cuthbert's Church. 2015. Seascale Parish Profile, Seascale UK. Web. Accessed March 2018.

Stiles, Kristine. 2016. Concerning Consequences, Studies in Art, Destruction, and Trauma, The University of Chicago Press, Chicago and London.

Temperton, James, "Inside Sellafield: how the UK's most dangerous nuclear site is cleaning up its act", Wired, 17 September 2016. Web. Accessed January 2017.

Tickell, Oliver. 2014. "Leaked Sellafield photos reveal 'massive radioactive release threat'", The Ecologist, 27 October 2014. Web. Accessed January 2017.

Footnotes

- The Ministry is now known as the State Emergency Services, under the jurisdiction of the Ministry of Internal Affairs Ukraine. ↩

- To parallel the 100 years life expectancy predicted for the as-yet unbuilt New Safe Confinement to be placed over the damaged Reactor 4 in 2016. ↩

- Michiel Dolk, discussing the earliest Chernobyl works, Fieldwork I and Fieldwork II, and noting the visual absence of people in my work, suggests that Fieldwork, as it applies to my work, could also be thought of as "a field requiring the viewer to do the work as an absent figure expected to improvise its own narrative." (Dolk 2009). ↩

- Still others can be found at Kiritimati, Malden Island, and Orford Ness in the UK. ↩

- Since the report came out, the nuclear dump proposal has been rejected by the government-appointed citizens jury, by the traditional owners, and by the state opposition. The Federal Government supports the proposal. ↩

- James Temperton is one of the few journalists to gain access to Sellafield in recent years. His account in Wired of the current state of the plant is compelling reading (Temperton 2016). ↩

- The images are no longer available in their entirety on The Ecologist site. You can see the album here. (INSERT LINK TO "LEAKED PHOTOS ALBUM"). See also Oliver Tickell's original article (Tickell 2014). ↩

- For more about the heightened state security around nuclear sites in the UK see www.gov.uk/government/news/work-underway-on-39m-nuclear-training-centre--2 ↩

- Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (United Kingdom) ↩

- There's an introduction by Chim↑Pom to Don't Follow the Wind in The Nuclear Culture Source Book (Ele Carpenter 2016:11,77). ↩